Reflections on Microfinance and the Care Economy

With rollback of the developmental state under the neoliberal policy regime, financial inclusion has come to be adopted as a developmental strategy. Micro-credit schemes, which were initially promoted as tools for gender-empowerment and poverty alleviation, have in the process become increasingly absorbed within the sphere of mainstream private finance. The relatively low rates of default in this sector have attracted an influx of funds from profit oriented financial institutions. The focus has shifted from the sustainability of income generation for borrowers to that of the profitability of the lending institution. Given the higher transaction costs associated with small loans and extending outreach to marginal low income households this change of focus has undermined the social mission of microfinance to reach the poorest and most neglected households. Social priorities are being subordinated to commercial considerations.

The impact of micro-credit on both poverty and gender relations has been extensively studied. However, the implications of the growth of micro-credit for the care-economy, and their repercussions in the wider macro-economy have received less analytical attention. The neglect of the implication microfinance for the provision of care labor is surprising in the light of the original mission of microfinance, which targeted the female worker in rural areas in developing countries, with less access to earning opportunities and disproportionate responsibility for the care work. The increase in market labor implies a claim on the time of working women. In the absence of social provisioning of care, this claim on the labor time of women could lead to a squeeze on the time of rural working women

A simple two-sector post-Keynesian model allows the integration of the role of demand and care work into the analysis of microfinance. This investigation demonstrates is that micro financed enterprises face a structural constraint on the demand side from overall macroeconomic conditions, and on the supply side from the responsibility for unpaid care work borne by the female beneficiary of microfinance. Paradoxically, microfinance has been espoused as a developmental strategy in precisely the period when the role of the developmental state has been eclipsed, and cutbacks in public spending on care provisioning have been prescribed.

Slowdowns in the wider economy, would lower the demand for the output of the microfinance sector, and hence undermine the viability of these enterprises. The capacity of the microfinance sector to provide the impetus to broader demand growth in the economy is likely to be more limited in the absence of public policies to stimulate demand and investment. The capacity of microfinance to alleviate poverty and lift incomes is thus dependent on conditions in, and linkages with the wider macroeconomy. A vibrant and stable macroeconomy is the only sustainable basis for a stable microfinance sector.

We also draw attention to some of the complexities of the impact of microfinance on the provision of care. The home-based nature of microenterprises perpetuates the gendered asymmetries of care responsibility within the household. While higher female earnings can alleviate the burden of care by making care work more effective and by enabling the market to substitute for unpaid care, at the lower income levels and in a context of the inadequate social provision of care the gendered responsibility for care remains a critical constraint for the female beneficiary of micro-finance.

Some clear policy prescriptions emerge from this investigation. Donors and development agencies have been encouraging raising interest rates in order to ensure the viability and profitability of microfinance lenders. Our model suggests that high-interest rates will actually undermine the scope of microfinance as a path to better and sustainable livelihoods for poor households in rural areas. Higher interest rates in this sector impose a higher burden on the labor time of the female worker with a consequent squeeze of care-labor or the own labor time.

More significantly, the analysis suggests that microfinance cannot be an effective path to poverty alleviation or gender empowerment unless it is backed by investment in the social provisioning of care. The success of microfinance as a developmental strategy depends on wider policies that support demand and the social provision of care. There is, in the final analysis, no substitute for a developmental strategy based on public investment in support of both job creation and social provision of care.

This blog was authored by Ramaa Vasudevan and Srinivas Raghavendran are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in Economic Modeling, Gender Inequalities, Rethinking Macroeconomics

Digital Forum on Reopening Long Island and Building a Fair Economy:Care Work in the COVID Crisis

Earlier this month, the Hofstra Labor Studies and the Center for the Study of Labor and Democracy in collaboration with Long Island Jobs with Justice and A.L.L.O.W. (Advancing Local Leadership Opportunities for Women) conducted a virtual forum addressing care work in the context of COVID-19. This discussion emphasized the financial and mental health challenges associated with all types of care work during this pandemic, and the immense need to address and resolve these issues in order to assist with a fair and sustainable economic recovery. Although the discussion is focused primarily on Long Island and New York, the problems indicated are applicable to care work throughout the U.S.

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that the unemployment or the stress of juggling work and home life as a result of the crisis has hit women much harder than men. This discussion utilized academia as an example of this, drawing upon data indicating that academic journal submissions have greatly increased among men since the beginning of the pandemic, but sharply decreased among women. For those working in academia, publishing work is crucial to professional advancement.

The pandemic has also shed a harsh light on the fragility of the overall childcare system in the U.S. Many families lacked adequate childcare even before the pandemic, forcing them to rely on unpaid care work. These existing issues paired with the recent closures of childcare facilities has exacerbated the problem.

Although the CARES Act did include childcare support, New York receiving $164 million going toward the childcare industry to provide protective equipment and cleaning supplies, the panel argues that while helpful those measures still did not provide adequate relief. The HEROES Act could potentially provide further relief for the care industry, but participants of this forum are less than optimistic about it providing the level relief needed.

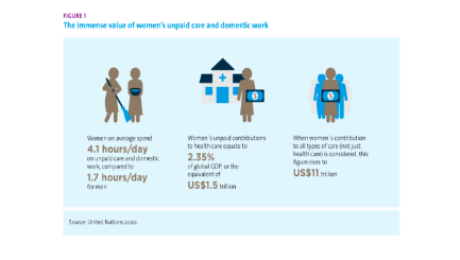

The International Labor Organization estimates that three-quarters of unpaid care worldwide is provided by women. In the U.S. women provide 37% more unpaid care work than men on a daily basis. Among care providers in the U.S., Hispanic women do the majority of unpaid care and account for the biggest gap among men and women. Beyond traditional gender roles, this is largely tied to economics; oftentimes men have opportunities to make more money. But generally speaking, even when both parents work full time, women are still taking on more unpaid work even if they are earning more money than the male figure within the household.

There is also a societal tendency which expects care workers to be exceptionally giving. This is highlighted in the fact that even within paid care work positions, there is a fair amount of unpaid work being performed. For example, staying with an elderly person at their doctor’s appointment a couple of hours after the official workday has ended. This is a constant strain within the care industry, and COVID-19 has increased the pressure on this component of unpaid work within the paid care industry.

Additionally, the many racial and ethnic disparities within care work serve as a microcosm of larger racial inequities prevalent in society. For example, in New York, 80% of care workers are women, and a large majority of them are women of color. Furthermore, care workers in New York typically make minimum wage yet are still known to go above and beyond in their roles to ensure the best care is provided, regardless of whether or not it is part of their job description. This existing issue has been pushed to a new level due to COVID-19; now many of our care workers are putting their lives on the line.

Part of the reason that low wages are prevalent within the care sector is the historical association that care work is a “women’s job,” coming naturally and requiring little skillset. This sentiment in the U.S. is compounded by care work being viewed as the responsibility of the individual. The decision to have a family is viewed as a personal choice, therefore the basic needs of childcare are the sole responsibility of the parents, not something to be addressed via larger social safety nets.

New York is facing a particularly troubling dilemma within its care work industry. Despite the fact that a large majority of the workforce is comprised of immigrants, the guidelines that have been released outlining protection measures from COVID-19 are only available in English. This is concerning given that some workers may not yet possess the English language proficiency necessary to fully comprehend these guidelines.

In order to address these strains within the care work industry, political will and national policy are needed. The U.S. Department of Defense provides an exemplary model that could be emulated on a national scale. This government sector presently has one of the best childcare systems available in the U.S., operating on a sliding scale making it accessible to all those within the department that need it. This allows these federal employees to perform their duties with the comfort of this social safety net.

Furthermore, at the local level, immediate state, and county-level funding for care work can have a significant impact on the accessibility needed during this stressful time. Without swift action on the policy level, the issues discussed will continue and have detrimental effects on not only families, but economic recovery as well.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in COVID 19, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy, U.S.

COVID-19 AND THE CARE ECONOMY: UN Women calls for immediate action and structural transformation for a gender-responsive recovery

A recent brief from UN Women presents emerging evidence on the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic on the care economy.

Evidence suggests that the rising demand for care in the context of the COVID-19 crisis and response will likely deepen already existing inequalities in the gender division of labor, placing a disproportionate burden on women and girls. Not only are women over-represented among paid health care workers, girls and women also shoulders the bulk of unpaid care and domestic work that sustains families and communities on a day-to-day basis.

School closures and household isolation across the globe are moving the work of caring for children from the paid economy—schools, day-care centers, and babysitters—to the unpaid economy. So far, 1.27 billion students (72.4 percent) across 177 countries have been affected by school closures (UNESCO). The lack of childcare support is particularly problematic for essential workers, including those in the health sector, who have care responsibilities.

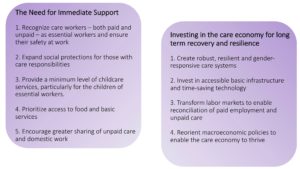

This brief recommends ways to transform care systems now and for the future – both the need for immediate support and the need for sustained investment in the care economy for long term recovery and resilience.

How to Transform Care Systems – Now and for the future

(UN Women, 2020)

Authors/editor(s): Bobo Diallo, Seemin Qayum, and Silke Staab 2020

- Published in COVID 19, Policy Briefs & Reports, UN Women

The True Cost of Caregiving: An Aspen Institute Digital Discussion

Even in a typical year, U.S. households are estimated to experience $31.9 billion in lost wages as a result of inadequate childcare and paid leave. Roughly 1 in 5 people living in the U.S. today incur caregiving expenses, and the need for care work is experienced in nearly every household at least once. Those who are professional care workers, disproportionately women of color, are underpaid and therefore susceptible to financial insecurity. Those insecurities have been exacerbated even further amidst COVID-19 and the resulting economic downturn.

In June 2020, the Aspen Institute Business and Society Program hosted a digital discussion “Paid Leave, Livable Wage, Affordable Care: Policies that Could Avert the Next Crisis” in conjunction a policy brief “The True Cost of Caregiving” that was released in May. Within this discussion, the panel focused on the fragility of the care system and the financial stability of those providing care, both paid and unpaid. The panel not only addresses these issues but seeks to re-imagine a system in which care is treated like a public good, examines the hierarchy of human value, delves into the historical context behind care work in the U.S., the vulnerability of care workers in the current pandemic, and the inefficiency of the current care economy within the larger economic system.

A number of important questioned are addressed such as:

– How to quantify the benefits of paid leave, livable wages, and affordable care policies?

-What are feasible policy responses to COVID-19, in both the short term and long term, that can lead to better systems of caregiving in the U.S?

-What does an inclusive and equitable care system could look like?

-Who bears responsibility for building this system?

Further, this panel brings to the table the idea that care work should be invested in collectively as a nation, as opposed to being looked at as an individual burden; which puts increasing downward pressure on those who are already disadvantaged in the U.S. due to race and gender.

Policies that address these concerns could assist in not only building a more equitable system of care but have the potential to aid in averting future crises like that which the care economy finds itself in today.

- Published in Child Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy, U.S.

Inequalities in access to U.S. care services

In the U.S., states and localities are beginning to ease social distancing policies resulting from the pandemic. With many workplaces calling Americans to return to work, the nation’s care services system, what was already broken, is now in dire need of repair or replace.

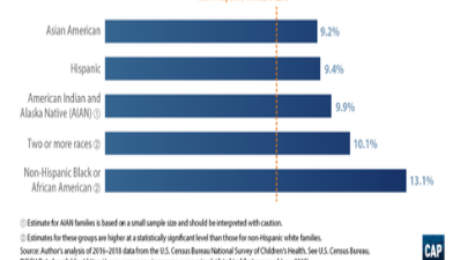

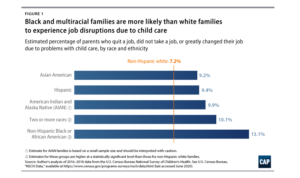

According to a recent analysis by the Center for American Progress (CAP), the lack of adequate child care services in the U.S. negatively affected communities of color before the pandemic, as parents of color were more likely than their non-Hispanic white counterparts to experience child care-related job disruptions that could affect their families’ finances.

The analysis uses the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to show that before the pandemic, Black and multiracial parents experienced child care-related job disruptions—such as quitting a job, not taking a job, or greatly changing their job—due to problems with child care at nearly twice the rate of white parents.

For Black workers and workers of color, decades of occupational and residential segregation has translated to less access to telework, and therefore less flexibility within their responsibilities for young children or elders. In fact, most Black workers and workers of color (especially those who are women) have had to work through the pandemic in essential frontline occupations.

The analysis shows that prior to the pandemic, adequate and affordable child care services was short in supply, particularly for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous families. In fact, more than half of Latinx and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) families have experiences living in a child care desert – which is an area suffering from an inadequate supply of licensed childcare.

Using child care services as an example, the analysis shows that disparities will likely worsen in the aftermath of the pandemic. A previous CAP analysis estimated that nearly 4.5 million child care slots could disappear permanently as a result of COVID-19, effectively cutting an already inadequate child care supply in half. Recent data suggest that this impact is already being felt, with more than 336,000 child care providers—many of whom are immigrants, African American, or Hispanic—losing their jobs between March and April.

Allowing care services to flounder should not be an option; a broken and inadequate care system would slow the nation’s economic recovery and in addition to deepening existing economic and racial inequalities.

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Race Inequality

The Covid-19 Care Penalty

In the U.S., as elsewhere, essential workers have been rightly praised for their willingness to take on additional risk and stress. Their commitment to helping patients, students, and customers face-to-face went beyond the ordinary requirements of earning a paycheck. Yet some essential workers faced more serious risks of infection than others, and differences in pay among them were also significant. The abrupt creation of a new category of workers based on social need, rather than market forces, dramatized an important question: why do we often see a disjuncture between the social value of work and its private, pecuniary reward?

Feminist research addresses this question in a number of ways, emphasizing factors such as employer discrimination, monopoly or monopsony power, and intersectional differences in the relative bargaining power of distinct groups of workers. The distinctive features of care work—intrinsic motivation, emotional skills, team production, and positive spillover effects—have also received attention. Leila Gautham, Kristin Smith and I have been building on previous research on care penalties to show that essential workers in care services (health, education, and social service industries) are paid less than other essential workers (in law enforcement, support and waste services, transportation, agriculture, retail and financial industries) with comparable personal and work characteristics, a pattern with especially costly consequences for women. Low-wage workers such as health aides are especially vulnerable, but care penalties also help explain the vulnerability of doctors and nurses in ways mediated by unique institutional features of the U.S. health care system.

A paper on this research is now under review. Once this process is complete, I’ll come back with more details.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on June 11, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in COVID 19, Feminist Economics