Getting to a mainstream market is possible in carbon removal; here’s some thoughts on how

“A bit of advice given to a young Native American at the time of his initiation:

‘As you go the way of life, you will see a great chasm.

Jump.

It is not as wide as you think.”

― Joseph Campbell

Welcome back! I’m writing this as a companion post to Part 1 where I proposed that CDR is at a ‘chasm’ point between an early market and a more mainstream class of customer. In this post (Part 2 of 2), I will offer some suggestions on how a carbon removal project developer might make that transition. Once again, I’ll adapt key principles from Geoffrey Moore’s Crossing the Chasm to durable carbon removal, this time talking about specific actions which early stage companies can take that might yield success.

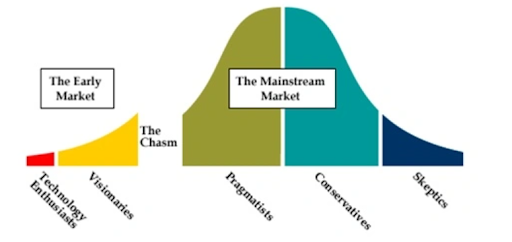

As a reminder, here is a graphic of Moore’s technology adoption lifecycle curve:

And a shorthand reminder of the three segments most in play for CDR now:

-

-

- Enthusiasts (AKA Innovators) who are most interested in technology for technology’s sake.

- Visionary customers who want to be the first to implement new solutions as the start of revolutionizing the way businesses operate.

- Pragmatists who are Mainstream customers less interested in being the first to lead, desiring lower risk products at higher volume, with more sensitivity on price.

-

Because these Mainstream customers are qualitatively quite different in their needs from Early Adopters, succeeding with that group is akin to bridging a marketing Chasm.

Achieving product adoption in this third, Pragmatist group requires a different set of tools compared to the first two. To that end, based on my reading of Moore’s principles here are some strategies that I have adapted to durable CDR.

A: Target a segment of customers, not a whole market.

Moore talks a bit about finding a market larger enough to be A) financially meaningful but B) small enough that a company can achieve at least 50% of market share among those customers. Pragmatist customers are seeking ‘the market leader’ no matter what that market might be – this group might be geographically defined, or psychographically defined, but the critical point is to define a small enough segment that you can dominate while still making meaningful financial gains.

Many companies fail by trying to define their market too broadly: “We’ll target all of forestry with our innovative CDR solution!” is, for a startup, an impossible task. Venture investors do like a 10-year ‘hockey stick’ growth curve showing how the company (and its investors) could be zillionaires…in 2037; but they also really like a startup who shows how the initial, well-defined, smaller market segment will get the company through the next 2-3 years. Defining and dominating a tiny segment of the market and getting your business started among mainstream customers in that group is a way to win.

Examples: Carbicrete is manufacturing cast concrete pieces using CO2 as a feedstock. It would be one thing if they were to target “all concrete producers” – a daunting task. Rather, they fixate on a specific starting point that would likely yield success, and then build from that initial group of customers in which the solution you provide is the dominant one. Example 2: Goal300 is targeting Christmas Tree farms in the Pacific Northwest as customers who would apply enhanced rock weathering to soils. It’s a specific type of customer, who has a customized set of needs, but large enough to get the business started to bridge later to a more mainstream market.

Generating reference customers through word of mouth is the goal here. One mainstream Pragmatist customer will talk to other Pragmatist customers about their product experience: as they are more risk averse relative to Visionary customers, they value the assurance of having another person’s opinion on a product before buying it. Cast concrete purchasers who speak to other cast concrete purchasers. Christmas Tree farmers who talk to other Christmas Tree farmers in a particular region.

Talk to a variety of customers in different segments when thinking through which one to target. And also listen for the needs of various internal stakeholders within that customer company (more on this coming up in Part ‘B’ below!).

A great way for such customer discovery is to attend the industry conference for that particular customer segment! Learn who they talk to, and how they relate to each other, and what their common needs are. Because insofar as a market exists, it moves at the speed of word of mouth from reference customer to reference customer, building momentum for success among the first mainstream segment to target, so that the product can get adopted by other segments after establishing itself as the market leader in that initial ‘beachhead’ segment.

B: Figure out how to satisfy three crucial stakeholder roles in your target customer.

Those influencers within the customer entity, per Moore, are:

-

-

- The end-user: who uses the product you sell

- The technical buyer: who evaluates the qualifications of your product

- The economic buyer: who provides the financial resource to pay for the product

-

To illustrate, I’ll use the best non-climate example from my professional experience in pharmaceuticals:

-

-

- The end-user is the patient, who uses the product to combat a disease

- The technical buyer would be the physician prescribing the pharmaceutical, based on their expert evaluation of the attributes of the product

- The economic buyer is the private or government insurance company – a ‘Payer’ in pharma industry terms – or in some cases the patient themself who pays for the pharmaceutical intervention.

-

For durable CDR companies in a voluntary carbon market, the end user could be the corporate sustainability professional who uses the carbon removal credit to report on the Net Zero goal achieved through offsetting (or insetting). The carbon removal purchase itself serves a useful purpose to that individual.

The technical evaluator could be an outside consultancy or internal group of technical people hired for the purpose of understanding the project(s) in play. Unlike pharmaceuticals, there’s no state-mandated licensure for prescribing CDR tonnage! A select few companies have large numbers of in-house technical staff who evaluate CDR projects as they come in. Most mainstream companies will not have these resources, and as such would rely on an intermediary, such as a marketplace, broker, or consultancy to provide that technical diligence.

The economic buyer is typically the Finance department, where price for tonnage would be paramount relative to other projects that are recommended by the sustainability department – and external or internal evaluation teams. As I wrote previously, one way to convince a CFO is to demonstrate tangible economic value by pursuing the carbon removal project. Bundling the CDR credit through insetting with a physical product, or otherwise selling the physical product of carbon removing activity alongside a separate unbundled offset represents a revenue-generating prospect for the CDR company who can sell a physical product while removing excess atmospheric greenhouse gas. Note that there are many different types of projects, and not just offset projects, that the end-users and technical buyers would recommend. So valorizing the ROI is a pathway to be persuasive to the economic buyer audience, per CDR.FYI’s 2025 Market Survey.¹

C. Market the whole product, not just the core product

An early stage Visionary buyer typically has performance expectations for the core product itself, and is willing to forego the supportive services that would make the purchase easier to handle. Pragmatist customers’ view is the opposite: they need surrounding product or service offerings that make the purchase easy to integrate into their existing business.

For a Pragmatic class of CDR customers this could mean: insurance services, credit ratings, or even marketing materials that enable the sustainability office to feature the project in an ESG report.

In particular, one big concern among Pragmatist customers is that the CDR supplier will go out of business, leaving them with an unsupported amount of CDR tons that they would have to answer questions about. Demonstrating post-sale customer support and contingencies would address this risk.

Selling a ‘whole product’ could also mean working with a broker or other intermediary who would package the durable CDR credit with other credit types, such as lower priced nature-based carbon removal, avoidance/REDD+/Renewable Energy offsets, or industrial waste gas destruction credits. That would lower the average price per ton of the entire ‘market basket’ while providing different qualities of offset to the buyer. Rather than competing for a vanishingly small attention span for CDR, the offset would be considered alongside other types of projects on offer for a Sustainability office.

So how can a CDR project developer start to make the leap?

While these three tactical suggestions could be useful for durable CDR companies to make inroads into a market of Pragmatists, the greater issue could be making the internal leap of faith required to adjust to these market forces.

The thinking surrounding pursuit of an early stage customer – heaving a technically less polished, core product over a RFP Visionary transom and, well, praying – is not a strategy that would work to gain market traction among Pragmatists. Adjusting one’s own approach to understand the mindset of the mainstream customer, respect their needs and motivations, and meeting them where they are at will be the way to success. That’s why identifying that one small niche of a Pragmatist market is so important.

Oftentimes in other industries this has meant that the visionary startup founder does not have the skills or interest to speak on equal terms to an otherwise risk-averse customer. Visionaries are great at speaking with other visionaries; pragmatists with pragmatists. So it follows that bringing in new talent to meet broader mainstream needs might have the uncomfortable task of replacing a founder for the sake of company survival.

Getting across a Chasm is not an easy task. But, a necessary one in order for an early stage company to achieve its potential. In carbon removal the results can be worldchanging, provided the durable CDR company has the right tools and, more importantly, internal mindset to adjust and make the leap. It’s a challenge to be sure but one that is possible to achieve.

Jason Grillo is the Principal of Earthlight Enterprises marketing consultancy, Co-Founded AirMiners, and is a voluntary contributor to CDR.FYI. The opinions expressed in this writing are the author’s own and do not reflect the position of any employer or associated organization.

¹Disclosure: I was a voluntary contributor to help that effort.