Literature Review Series

Authored by Wil Burns, Co-Director, Institute for Carbon Removal Law & Policy, American University

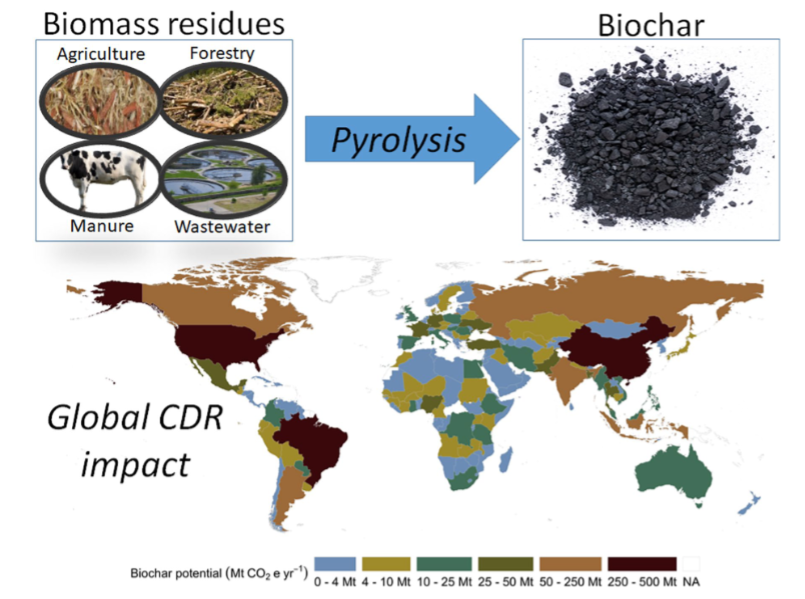

To date, the vast majority of purchases of durable carbon dioxide removal have been for biochar, a process that can transform biogenic carbon dioxide into a far more stable form via the process of pyrolysis. Pyrolysis is a thermal process that, in the absence of oxygen, can deconstruct bio-polymers into, among other things, biochar, a charcoal-like substance that can securely store carbon for hundreds to thousands of years when applied to soil. Conversion of biomass to biochar can sequester 50% of initial carbon, compared to 3% associated with burning, or less than 10-20% after 5-10 years from biological decomposition.

Image Credit: Lefebvre, et al. The above image is a graphical abstract.

A number of studies in recent years have suggested that biochar potential could be much greater in the future, perhaps in the range of 3.5 GtCO2/yr., or up to 350 Gt during this century. However, to date, studies have focused on global or regional aggregate estimates. In a recently published study, researchers led by David Lefebvre of the University of British Columbia sought to extend these analyses by assessing the potential of biochar sequestration in each of 155 countries. The study restricts itself to the assessment of sequestration potential associated with biomass residue feedstocks in the contexts of agriculture, forestry wood residues, animal manure, and wastewater biosolids. The study also presumes that 30% of residues are left in the fields in the interest of maintaining long-term soil health.

Among the conclusions of the study are the following:

- Four countries, all characterized by large populations, land areas, and agricultural sectors have the greatest potential, including:

- China: 468 Mt CO2e/yr.

- United States: 398 Mt CO2e/yr.

- Brazil: 303 Mt CO2e/yr.

- India: 225 Mt CO2e/yr.

- North America and South America are characterized by a large number of countries with biochar sequestration potential of 25 Mt CO2e/yr., with bands of relatively low potential across North Africa into the Middle East, with low potential in portions of Europe and southern Africa.

- 28 countries have the potential to sequester more than 10% of their CO2 emissions with biochar, with the largest number in Europe

- The “conservative approach” of the study (including assessment of only recalcitrant carbon with permanence factors based on national averages) yielded an estimated carbon dioxide removal potential of 6.23% of total greenhouse gas emissions of the 155 countries in the study.

Notably, the researchers observed that its estimates didn’t take into account a number of potentially compelling co-benefits, such as potentially reducing emissions of methane and nitrous oxide, enhancement of crop yields and displacement of fossil fuels. Any effort to assess the potential costs and benefits of biochar deployment in individual countries, as well as globally, will require a more granular assessment of these factors, suggesting one potential research tributary flowing from this study.

Overall, this study could prove extremely helpful in helping to operationalize biochar programs nationally, and regionally, moving forward. It suggests that biochar could play an important role in the carbon dioxide removal portfolio of many countries.