TL;DR working to find a job in carbon removal can be hard work itself – some advice below on how to find the right team fit.

“Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom” – Aristotle

Part of my dream for the carbon removal industry is a future where many thousands of people find gainful, meaningful employment for work to remove the legacy of excess greenhouse gas. For that vision to become reality – removing the first one billion tons before we believe it is possible today – requires a workforce that is educated, trained, and well-matched for the CDR jobs of the future.

To that end, through the people I’ve been lucky to meet in the carbon removal industry, I’ve been asked quite a bit about how to find a job in CDR. When welcoming new folks into AirMiners, the question of how to find a job is probably the topic most on the minds of those who are new to our community. That’s why in AirMiners we’ve done two events ( about this topic – Heidi Lim in particular has some excellent (and oft-cited advice) here.

One pillar of this is: how much can I expect to earn in carbon removal? And that data has been difficult to find. That is, until today with the release of an excellent global salary report created by the CDRJobs.earth team led by Sebastian Manhart.

Building on that hope for finding a job that inspires the best of you is why I’m writing this for you as a CDR job-seeking reader: to help you save time by asking three questions of yourself, about what makes you most effective to direct your efforts to fruitful career goals.

Please note that these self-revealing questions constitute my own personal advice, and your own results may vary.

First, what is your one functional superpower that you bring to the table when approaching a carbon removal company? To be blunt: what is the one thing that you could do immediately in a new role without any on-the-job training?

‘Functional expertise’ could be marketing campaign creation, operations or program management, corporate financial expertise, or any one of a wide variety of technical skills. And what concrete results have you driven in executing on this skill? In business school my classmates and I practiced the STAR framework to handle interviews: Situations,Tasks, Actions, and Results. What was the Situation you found yourself in, what Tasks were before you to achieve, what were your Actions to attain that goal, and what were the Results you ultimately arrived at. Quantifying those results is especially important: “I developed R or Python to research and analyze X number of deep datasets” “Our marketing campaigns achieved a 200% ROI!” / “We delivered this $5M project ahead of schedule and below budget” marks the success that attracts interest.

Not to discount passion – which is important – but a Grade ‘A’ record of performance plus passion is a compelling story. At the time of this writing, our industry is still in an early enough stage that top functional expertise from different industries will find a ready-made home. Not many have been in CDR for more than five years (myself included!), so bringing a strong transferable set of skills is by far the best way to build a compelling narrative to land a new role.

Second, what type of carbon removal do you like best?

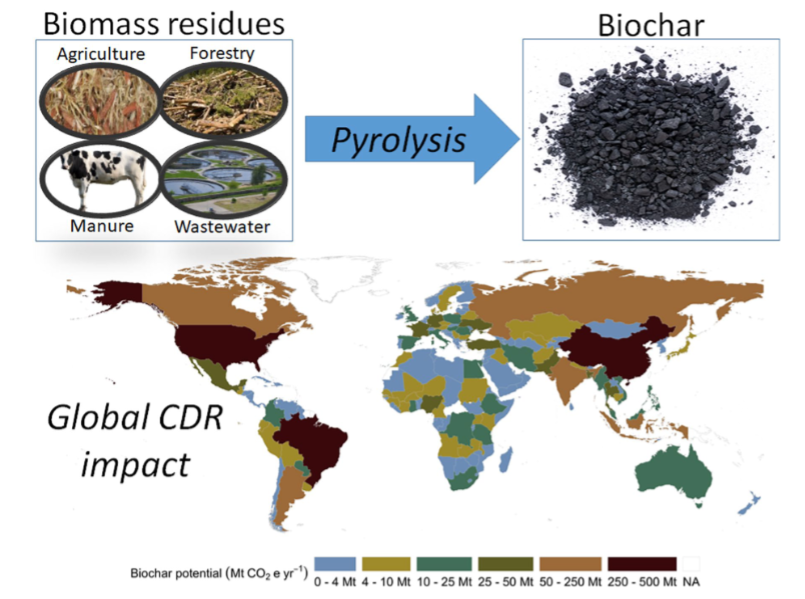

There are a wide – and I mean wide – variety of CDR methods on offer in these early years of the carbon removal industry. The trick is to figure out which type of CDR suits your skills and interests – as soon as you can – which makes career searching in CDR much easier. That way as a job seeker you can home in on how the superpower identified above can be useful in, say, marine CDR, Direct Air Capture, biochar, enhanced rock weathering, Measurement/Reporting/Verification, or any other type of carbon removal technology that provides meaning to you.¹

Carbon removal is a new enough industry that you as a job seeker can ask yourself what sparks your interest in a particular method of carbon removal. What is it about that method that makes you like it more than others, at a high level? If you don’t have that perspective, fortunately AirMiners own BootUp program² provides such an entry point, offering a broad overview of state-of-the-art CDR methods over the course of several weeks.

Most importantly get out and talk to people who are starting up these organizations! Find them on LinkedIn, at networking events, even (gasp) in our main AirMiners community or elsewhere. Ask yourself whether you can envision you working at the type of jobs for people in that method of CDR is a good fit.

Third question: what size organization would you like to work at? The landscape of carbon removal is very much the landscape of startups, though the term ‘startup’ covers a lot of ground in terms of risk and reward. Maybe you are a founder of a company. Maybe you are Employee Number 5, or Number 25, or Number 125 – all of those are new, small STARTUP businesses, with a high degree of risk around technological approach or business model.

The real introspection to work on is: “in what environment am I most effective at driving results?” Will your 1 or 2 skills from Question 1 above be best unleashed with structure and resources? Or with freedom and latitude without as much to fall back on? Every person has different preferences – and prefers things at different points of their career, especially when factoring for personal and family needs.

The larger a company, even along the more differentiated a role tends to be, and possibly the more hierarchical. Smaller organizations tend to be flatter, favoring those who consider themselves generalists. Plus, compensation – especially for pre-revenue companies – would be more for equity rather than cash.

Different people in a similar situation could pursue widely varied pathways. For example a recent graduate might want to develop the one functional skill that they know they want to fulfill throughout the next several years of their career, then climb a career ladder or switch companies. Or another recent graduate would say ‘nah, I need my space’ and found a startup or two (or three) in their first years in industry. Knowing yourself and where your talents may best take root – that’s the essence of how to start a job search.

And an added bonus question: How effective might you be in a remote vs. hybrid vs. in-office work environment? The COVID pandemic led to the rise of remote work, with some reversal of that trend in recent years. Fortunately many CDR companies – including small startups – are willing to take a risk and seek talent from a truly global pool rather than limit themselves to a particular geography.

This post started off with the goal of developing a professional workforce in carbon removal; my hope is that you as a job seeking reader find the career journey a bit easier by asking questions of yourself to guide your job search in a new and growing field.

Thanks for reading, and wishing you good job hunting!

Jason Grillo is a Co-Founder of AirMiners. The opinions expressed in this writing are the author’s own and do not reflect the position of any employer.