Authored by Jenn Brown

Prepared for the Institute for Carbon Removal Law and Policy

The term “pipeline” tends to evoke strong reactions throughout many communities across the U.S. for various reasons. Many of these reactions are negative, and these feelings are not without merit. This concern around pipelines also expands beyond U.S. impacts as well, as the expansion of many pipelines is concomitant with the perpetuation of the fossil fuel industry.

In the United States, there are 2.8 million miles of regulated pipelines that carry oil, refined products, and natural gas liquids. These massive pipeline infrastructures have posed significant threats and damages to communities and environments throughout the country, and some of this can be attributed to aging infrastructure. For example, according to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, from 2001 to 2020, there have been 5,750 significant pipeline incidents onshore and offshore, resulting in over $10.7 billion worth of damages.[1]

This brings us to the issue at hand: how do pipelines that transport CO2 for both carbon dioxide removal and carbon capture utilization and storage fit into this picture?

It has become increasingly clear in recent years that carbon dioxide removal (CDR) will become a necessity for the global community to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. The recent IPCC AR6 Working Group I report released in August of 2021 reiterates this point. Even with the most optimistic modeling used in the report, limiting warming to 1.5˚C necessitates about 5 billion tons of carbon dioxide removal per year by mid-century and 17 billion by 2100. Some approaches to CDR might involve transporting CO2 via pipelines, but there are also many other approaches that do not necessitate the need for pipelines, such as enhanced weathering, agroforestry, and blue carbon.

One method of carbon removal that has received a fair amount of attention is direct air capture (DAC) in part due to the recently launched Orca facility in Iceland by Swiss company Climeworks. Furthermore, the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in 2021 includes $3.5 billion allocated to the construction of four “regional direct air capture hubs” and additional funding for CO2 pipelines. This effort is made with high hopes from the federal government that these hubs will result in the creation of clean energy jobs.

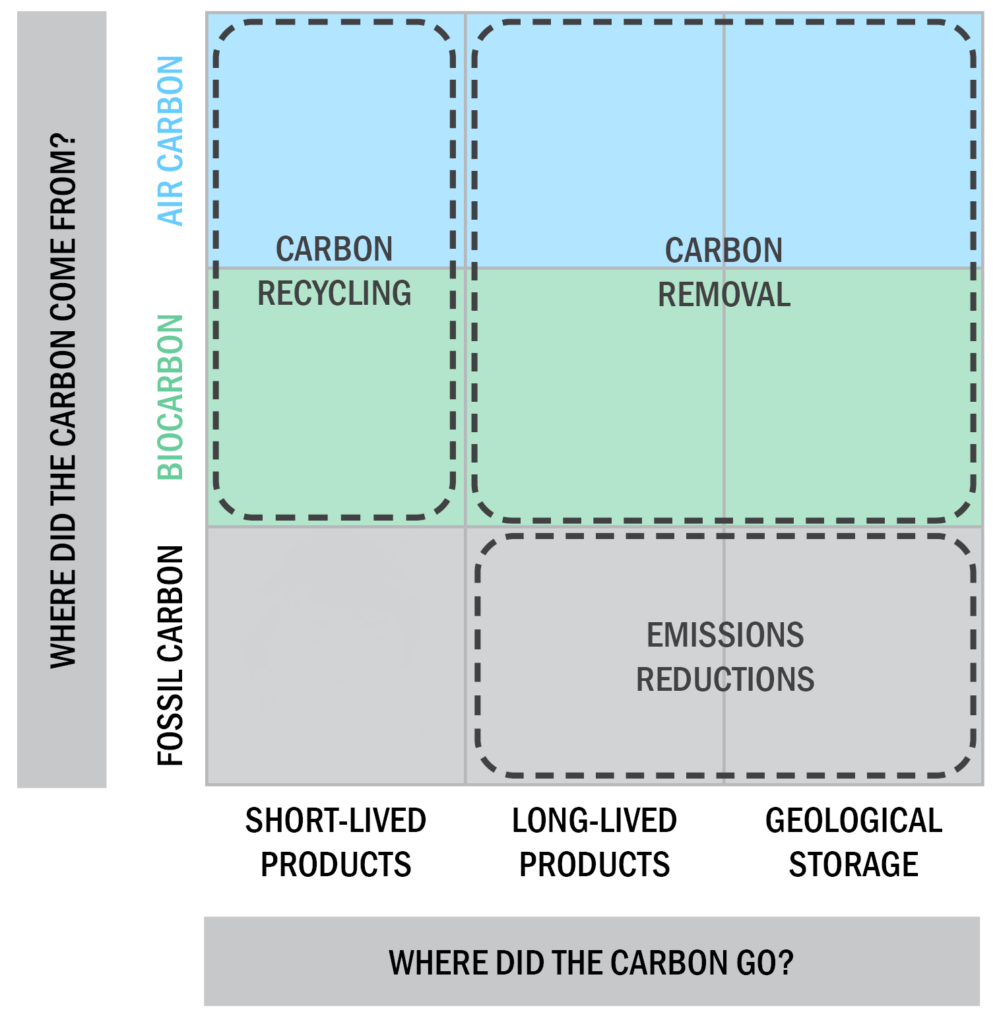

The carbon removed with DAC can be injected into the ground right at the plant where the carbon removal takes place, as long as the facility is located over appropriate geological formations. This is an idea known as colocation, which prevents the need for transporting CO2 altogether. But DAC could also possibly, to some degree, come to rely on the utilization of pipelines to transport the captured CO2 to sites where it can be injected into geological storage areas, or to facilities where it can be transformed into long-lasting carbontech products such as concrete.

These developments conjure an important question: are all pipelines created equal? Furthermore, does a CO2 pipeline intended for combating climate change warrant the same concern as oil and gas pipelines? Are pipelines needed to scale DAC or can CO2 storage happen onsite at a DAC plant?

As a starting point to help navigate this thorny and complex question, we turned to the expertise of three professionals working actively on these exact issues. Through these discussions, we sought out perspectives from the “yes,” “no,” and “maybe” stances on if the scaling of DAC depends on CO2 pipelines. As these viewpoints highlight, there is a range of perspectives when it comes to if the growth of DAC is reliant on CO2 pipelines or not.

The Experts

Xan Fishman, who is representing the “yes” perspective, is currently the Director of Energy Policy and Carbon Management at the Bipartisan Policy Center. Fishman previously worked for Congressman John Delaney as Chief of Staff. Through this experience, he became interested in DAC as a way of simultaneously addressing climate change and investing in various communities to create jobs, particularly in the Midwest.

Celina Scott-Buechler, who represents the “no” perspective, is a Climate Innovation Fellow at Data for Progress. Scott-Buechler’s work with the organization is on looking at how large-scale carbon removal can work in tandem with decarbonization in the U.S. Her work is also focused on promoting job creation and working alongside the environmental justice community to ensure these efforts do not fall into the traps of past infrastructure projects that did not have community support. She also served in the office of Senator Cory Booker through a one-year fellowship term working on natural climate solutions.

Rory Jacobson, who represents the “maybe” perspective, is Deputy Director of Policy at Carbon180, a D.C.-based NGO focused exclusively on carbon removal federal policy. Jacobson has spent the majority of his career focused on CDR, most recently at Natural Resources Defense Council researching near-term federal policies to incentivize deployment. As a graduate student at Yale, he advised Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry on myriad climate and energy issues.

What differentiates a CO2 pipeline from other types of pipelines?

Fishman points to the fact that much of the opposition to existing pipelines, particularly oil and gas, derives from the risk of spills and the implications that has for communities and the environment. Additionally, this perception is influenced by what the pipeline is transporting, which in the case of oil and gas is related directly to climate change via the resulting emissions that will cause further harm to communities and the larger environment. On the other hand, CO2 pipelines are part of the climate solution. Although careful consideration should be taken when siting pipelines, implementing safety precautions and regulations, CO2 pipelines are generally safe and do not carry hazardous waste, according to Fishman.

Scott-Buechler feels that how the public views these issues matters, and that pipelines, in general, have had very negative image “in particular because of the way these pipelines have been sited through indigenous lands without consultation, though environmental justice communities and other rural communities without consent, minimal consent, or at least with minimal information.” Due to this, combined with other prominent issues for many groups, especially within the environmental justice community, the idea of a pipeline is a nonstarter because of all the baggage it carries.

Jacobson points to the more technical aspects on top of important questions around equity and justice. “From an infrastructure and engineering perspective they (CO2 pipelines)are actually quite different from oil and gas pipelines, and this difference is quite important because we actually do not transport CO2 as a gas. We transport it as a supercritical fluid which means that the carbon dioxide is under such high pressures that it actually behaves like a liquid.” CO2 needs to be transported at 700 PSI higher than, for example, natural gas, meaning the pipeline walls have to be thicker than other types of pipelines. This also indicates that the repurposing of decommissioned oil and gas pipelines, although in some cases could be considered ideal, is not a feasible option. Even in instances in which engineering is perfectly compliant with regulation, past missteps nonetheless highlight the inadequacy of federal review for existing pipelines, and the need for greater oversight.

Are CO2 Pipelines Necessary for Scaling Direct Air Capture?

“The way that I think about direct air capture is that it is nascent. But to go from where we are right now to the scale we need to be a major factor in achieving net-zero, there is a long way to go…In general, the faster we are able to deploy, the faster we will be able to scale,” says Fishman. Additionally, he makes the point that in order to meet 2050 climate goals, it is more beneficial to begin scaling now versus 5-10 years from now. He also points to the fact that there are already 5,000 miles of CO2 pipelines currently in existence in the US. The 2020 Princeton University report Net-Zero America: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts has indicated significantly more pipeline infrastructure will be needed to achieve climate goals.[2] Furthermore, storage requires investment. Currently, DAC facilities are not yet at scale to bring in massive amounts of carbon dioxide and will probably not be for some time. Therefore, there is likely not enough CO2 being brought in by DAC technologies as of yet to warrant large investments into storage. However, there are many existing industrial sites utilizing carbon capture utilization and storage, and connecting those sites to existing sinks for sequestration requires pipelines. Sharing lines of transportation across sectors increases the likelihood that each of those industries will be able to get off the ground without having to build something from scratch. Fisherman argues that this makes economic sense and will assist in the overall success of DAC in the long run.

Scott-Buechler argues that more information is needed around how to make pipelines safer and better regulated, especially including community input. Furthermore, pipelines are likely to be a huge sticking point within many communities, therefore she predicts potential 5-10 year delays in CO2 pipeline rollout given the problematic history of other types of pipelines in the US. In looking at it through this lens, co-locations with DAC facilities will be key to deploying the technology (which is injecting CO2 captured from a DAC facility right where the DAC plant is located, such as the Orca plant in Iceland). She further points to the fact that there are enough opportunities for co-location and many other ways for the industry to consider storage in more creative terms. Therefore, Scott-Buechler makes the case that it is feasible to severely limit the number of pipelines needed to scale DAC.

Jacobson argues for the creation of a comprehensive task force responsible for building out both the geography and the safety standards required to ensure best practices. This entity would consider everything from pipelines to siting to public engagement, including designating appropriate locations for these pipelines with rich public engagement and consent, examining the construction, quality, and surrounding ecosystem of pipelines, and setting safety parameters for operation. Thoughtful planning of pipeline networks can help both limit the number of pipelines and the distances to which they transport CO2 from DAC projects. This is especially relevant in light of increased funding for carbon removal that we’re seeing in upcoming legislation and federal funding. In implementing projects such as the four regional DAC hubs included in the recent bipartisan infrastructure deal, federal agencies like the DOE can set the tone for future deployment, safeguards, and community engagement.

What are the factors behind these viewpoints?

Fishman takes into consideration the threat of climate change and looking at the IPCC’s recommendation for the removal of 5-10 gigatons of CO2 per year. “It’s not just about getting to net-zero, it’s about getting to net negative,” he says. There is also the possibility the global community will achieve collective climate goals later than needed, which will further increase the need for removals. In terms of looking at CO2 pipelines, he points out that other modes of transporting CO2 as an alternative come with their own set of complications, such as additional emissions. “The stakes are so high that not investing in a solution that it turns out we need, and it is fairly obvious as a potential path right now, I think would be a terrible mistake…There is an extent to which we built our way into this problem (climate change), and the real solution available to us is to build our way out of it,” he says. But the key is ensuring these solutions are built the right way, while also taking into consideration any environmental justice concerns.

Scott-Buechler has worked closely with environmental justice groups for quite some time, both on and off Capitol Hill, and has come to view issues around carbon removal through that lens. She indicates that potential leakage is a large factor behind the mistrust, and sees pipelines as a nonstarter with these groups. She points to Standing Rock, stating “pipelines at large have developed this larger than life personality when talking about carbon removal infrastructure…generally siting and permitting will be something that we as a carbon removal community will contend with.” She also points to the DAC hubs laid out within the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, arguing that these hubs need to prioritize development in communities, led by those communities and other public groups rather than private industry, especially in communities transitioning away from economic reliance on fossil fuel industries. Further, researchers and policy communities should focus funds in these areas to fill existing gaps in information.

Jacobson explains that equitable construction, development, and input are critical to communities that would potentially host these projects, and that thoughtful quantitative analysis can better articulate the need for if and how much DAC needs CO2 pipeline infrastructure. Other types of pipelines have resulted in infringement on tribal sovereignty and other disasters, and Jacobson says that resistance to pipelines comes for a good reason. “These groups have already bared the environmental injustice that the oil industry and natural gas sector have placed on them, and accordingly, we would like to not have another pipeline of risk in their community and backyard. That is completely understandable.” He makes the case that strong federal regulation paired with public engagement and science-based communication with the communities is the only path forward. Additionally, Rory acknowledged that there is likely to be a lot of resistance from wealthy and privileged communities not wanting to see these pipelines in their backyard, and likely have more resources than lower-income communities to push back — something that should also be considered and remedied in policy and process.

[1] Depending on the type of pipeline, what it is transferring, what it is made of, and where it runs, there are various federal or state agencies that have jurisdiction over its regulatory affairs. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission oversees Interstate pipelines. The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Administration oversees, develops, and enforces regulations to ensure the safe and environmentally sound pipeline transportation system. The United States Army Corps of Engineers oversees pipelines constructed through navigable bodies of water, including wetlands. State environmental regulatory agencies are also involved when it comes to pipelines that run through waterways.

[2] 21,000 to 25,000 km interstate CO2 trunk pipeline network and 85,000 km of spur pipelines delivering CO2 to trunk lines.