CfDs have worked in other markets; they just might work for durable carbon dioxide removal.

As momentum builds around durable carbon removal, one assumption keeps resurfacing: that compliance markets will eventually unlock the scale and stability the voluntary markets have failed to deliver. What we are missing is a bridge that establishes price certainty today while preparing CDR developers to compete in tomorrow’s compliance landscape.

One of the most effective financing tools may already be in our policy toolkit: Contracts for Difference (CfD). Borrowed from the renewable energy industry, CfDs could offer carbon removal the market infrastructure it needs to scale by guaranteeing a specific price, thus catalyzing investment and enabling long term planning.

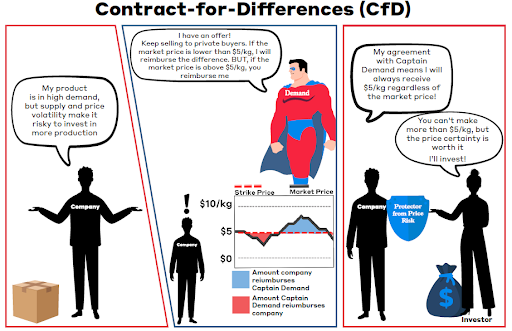

To start, let’s define what a CfD is.

CfDs are one of the clearest examples of smart public-private risk-sharing, and are used widely already in a different industry: energy. Contracts for difference have become a key market mechanism for scaling low carbon power (specially solar and wind) since its inception in 2014 in the United Kingdom. At its core a CfD guarantees a fixed price (Strike Price) for electricity over a long term (15 years in the UK). If the Wholesale market price (Reference Price) falls below this Strike Price the government pays the project operator the difference. If the Reference Price exceeds the Strike Price then the generator must pay back the excess to the government (Claw Back Mechanism).

Here’s a quick illustration, from a report by the Bipartisan Policy Center:

In the energy sector, this structure offers electricity generators a secure, predictable revenue stream while ensuring the “public” or rate payers recoup gains when prices are high. In doing so, the CfD evolved from a simple subsidy into a risk sharing financial hedge.

Why did the renewable energy industry adopt CfDs?

In the energy industry, risk defines value. Who carries it, who mitigates it, and who gets paid to take it.

The industry realized that one of the most effective instruments seen for rebalancing risk between public and private actors (without distorting the markets) is the CfD.

At its core, a CfD is a long-term financial contract that stabilizes revenue for power generators by hedging against market price volatility. But beyond the pricing mechanism lies its strategic importance: CfDs allocate risk to the party best positioned to manage it. Governments absorb short-term market volatility while developers retain responsibility for construction, performance, and resource variability.

It’s a clean split. And it works.

For governments, this isn’t just a subsidy: it’s a market signal, a risk management tool, and – in some cases – a revenue-generating hedge. Current CfD structures are designed to require the project operator to pay back any revenue it earns above the agreed strike price, allowing governments to claw back¹ the upside and when prices collapse, they guarantee the floor that makes projects bankable. The result is a scalable, fiscally responsible way to accelerate investment in critical infrastructure that can be applied to offshore wind, solar, or carbon removal.

How CfDs enabled renewables to scale

Before CfDs, intermittent renewable energy (offshore wind and solar) struggled under volatile wholesale markets. These projects were capital intensive and had unpredictable revenue. Enter CfDs, by absorbing price risk governments created the financial certainty that developers needed to build large scale infrastructure and commit to large scale projects.

Between 2015 and 2022, UK offshore wind saw a steep cost curve decline:

Developers responded by delivering massive capacity at ever-lower prices. For instance, the world’s largest offshore wind farm, Dogger Bank, secured its CfD in 2019 and achieved financial close soon after, clearing the path for a £9 billion project that began generating power in 2023.

By providing revenue stability, CfDs unlocked unprecedented levels of private investment, accelerating deployment and reducing clean energy costs in tandem.

The power of the two-way CfD lies in how it allocates risk between public agencies and private developers:

-

- Price risk: the wild swings in wholesale electricity prices is transferred to the public sector, which funds or collects payments. This insulation grants generators the confidence to plan and build.

- Volume and delivery risk related to actual performance, weather, and construction timelines remains fully with the developers, incentivizing them to manage and operate efficiently.

- Upside returns when markets boom are recaptured by consumers or taxpayers, thanks to the clawback mechanism. Meanwhile, developers receive a stable, long‑term income regardless of market volatility .

Why this could work in Carbon Dioxide Removal

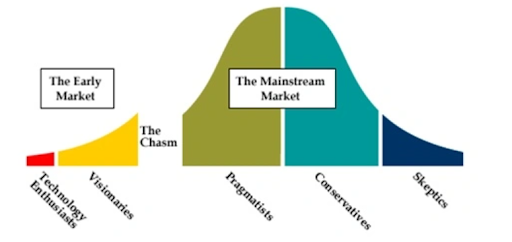

Much like renewable energy in its early days, durable carbon dioxide removal (CDR) today is trapped by three interlocking market failures: high upfront costs, no long-term price certainty, and limited bankability.

Removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is a critical component of any credible pathway to net zero; however, despite growing recognition of its importance, the market for durable CDR has not grown as much as needed to achieve climate goals. The problem doesn’t seem to be its technological potential, but rather, it’s a gap in the economic structure.

Developers face significant capital expenditures long before they can deliver a single tonne of removed CO₂. Outside commitment to substantial infrastructure investment is in many cases necessary upfront, with payback periods that are uncertain and years away. This happened already in the early challenges of offshore wind and utility-scale solar, which struggled to attract financing without predictable revenue streams.

At the same time, today’s CDR buyers (mostly voluntary corporate purchasers) offer no consistent long-term price signal. Carbon credit prices are fragmented and obscure, negotiations are bespoke, and there is a need for long term offtake agreements beyond a few years to support deep project financing. In this environment, even the most promising technologies remain non-bankable. Without a clear price floor or guaranteed demand, developers can’t raise debt, and equity investors face too much risk to deploy capital at scale.

Renewable energy broke through this impasse with the introduction of long-term contracts, in the form of CfDs. These contracts restructured risk: governments absorbed market price volatility, while developers retained delivery risk. By guaranteeing a fixed price for electricity for 15-20 years , CfDs enabled governments to shift market risks away from developers and unlock billions in private capital. This single innovation transformed renewables from speculative ventures into investable infrastructure. Today, CDR needs the same financial infrastructure.

CfDs for CDR can provide developers with the revenue stability needed to raise financing and commit to long term investment. And by anchoring demand though public procurement governments can send the same kind of credible signals that were so catalytic for renewable energy markets around the world.

The goal is simple: crowd in capital for durable CDR methods (DAC, BECCS, etc) by de-risking future cash flow and aggregating long-term demand. Furthermore, the promise of CfD contracts on the horizon would signify that carbon removal companies have staying power for the long term and thus encourage voluntary market buyers to purchase in the near term.

Project stakeholders would see benefits from the de-risking of durable CDR projects:

- Project developers want to be able to forecast price certainty going forward so that they can build out their revenue models and self-finance their expansion. For biochar developers, they would need this to purchase new pyrolysis equipment and expand their operations. For ERW, growing their feedstock and grinding operations would be needed, while DAC and BECCS players could use CfDs to achieve project financing to build new facilities.

- For governments, this achieves several purposes: a growing industry safeguarded by price through which they can expand their tax base. And it also enables them to hit a current (or future) carbon removal target on the pathway to achieving net zero emissions in their jurisdiction. To say nothing of the environmental or economic co-benefits from CDR projects.

- Investors especially would like to see this. To date, equity financing for carbon removal has been the majority of funding announced. As the industry matures, more stable carbon credit pricing and predictable revenue would be necessary to unlock debt and project financing.

How a CfD Auction could potentially work in CDR

In the UK, Contracts for Difference are awarded through competitive auctions:

Auction Administrator: the National Grid Electricity System Operator (ESO) is responsible for running the competitive auctions for Contracts for Difference (CfD). This includes pre-qualification, bid assessment, and notifying winners.

Contract Party: The Low Carbon Contracts Company (LCCC), a government-owned company, acts as the contractual party to the awarded contracts. It manages contract execution and makes (or receives) payments after projects become operational.

Policy Framework: The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) sets the overall policy and parameters for the auctions, including budget for each allocation round.

The auction:

-

- Renewable energy developers submit bids specifying the lowest price at which they are willing to supply electricity over the contract term.

- The government awards CfD to developers who offer the most competitive (lowest) strike prices.

- Payments Mechanism: once operational, projects:

- Receive top-up payments when the wholesale market price of electricity (typically the UK day-ahead market price) is lower than the strike price; or

- Pay back the difference if the market price is higher than the strike price.

- This mechanism allows excess profits to be returned to the public

Integration with Emissions trading systems

Not many emissions trading systems offer pricing that would support durable CDR projects at the time of this writing. As mentioned in the Philip Lee primer on CDR integration with emissions trading systems, the critical point is to index at a strike price below the Emissions Trading System (ETS) price per ton.

This mechanism provides incentive for project developers to lower costs, else reimburse the government for their price per ton. Governments would be incentivized to help with lowering the cost of financing for projects to achieve that lower price per ton as well – else the private financial backers may not enter into an agreement with the project developer to begin with and hence not provide any additional revenue to the government. The question becomes: at what credit price per ton would a financier find high enough in a strike price to ensure a sufficient Internal Rate of Return (IRR) for their own purposes.

What can CDR companies do today to advance the use of contracts for difference?

- Work with a relevant governing body to create a CfD reverse auction, using industry best standards for quality (e.g. private registries, EU CRCF, ICVCM CCP, etc)

- Get clear on what an acceptable carbon removal credit strike price would ensure profitability of operations, considering the CfD could be a long term contract backed by a government to unlock project development financing.

- Start mapping CfD cost benchmarks by CDR method on to provide to potential auctioneers to execute an auction by different CDR method type.

- Begin mapping for infrastructure – renewable energy, transportation, storage siting – that would support long term government contracting for large volumes of CDR tonnage.

Setting up these structures by 2030 would be crucial to unlock the promise of compliance markets to achieve carbon removal at high volume.

Isaac de Leon is a lawyer with over 15 years of experience negotiating energy and infrastructure deals across Latin America and Europe. After a career in oil & gas, he now helps shape the future of carbon removal, advising on legal structures, offtake agreements, and policies that unlock climate finance for the Global South.

Jason Grillo is the Principal of Earthlight Enterprises marketing consultancy, Co-Founded AirMiners, and is a voluntary contributor to CDR.FYI. This post appeared on the Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal blog.

The opinions expressed in this writing are each author’s own and do not reflect the position of any employer or associated organization.

¹A contractual feature in two-way CfDs that requires the seller to return any revenues earned above the agreed strike price. When market prices exceed the strike, the generator repays the difference, this locks in predictable returns for investors while protecting public funds from overcompensating projects. This mechanism turns CfDs into symmetric risk-sharing tools rather than one-sided subsidies.