KD #1: We can only scale carbon removal to relevant levels if we emphasize its economic benefits over its climate benefits.

I used to think carbon removal was a distraction from “real” climate action.

Like too many people working in decarbonization, I thought it was a red herring in the hunt for a sustainable future, a moral hazard enabling us (not just oil companies, but everyone) to continue emitting CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

I’ll come straight out and tell you that I no longer believe those things.

My name is Ryan Davidson, and for my full-time job, I’ve worked for a wave energy technology developer on business development, policy advocacy, and communications, among other things, since 2021. After a few years working on emission reductions, though, I realized reductions alone wouldn’t be enough to slow climate change to a halt. I understand I’m preaching to the choir here, but in spring 2024 it hit me just how vital removals will be, too.

I started learning about carbon removal in my free time in mid-2024, mulling over what my personal philosophy on the topic might be. I completed the AirMiners Boot Up program last fall (shoutout to AirMiners co-founder, and fellow IRCR contributor, Jason Grillo). During and after that time I met folks working in all corners of the CDR ecosystem who were kind enough to offer me their time and wisdom.

Semi-confident in my understanding of the vast world of CDR, last November, I started committing my thoughts to writing in Renaissance Carbon, a weekly Substack on the tech, politics, and culture of all things carbon removal. One of my main points – perhaps the main point – has been that we can only scale carbon removal to relevant levels if we emphasize its economic benefits over its climate benefits. While this has been (and will continue to be) especially true during the second Trump administration, I believe the point stands regardless of who occupies the White House.

One of my first Renaissance Carbon posts included a “10 Commandments of CDR.” We live in a different world now than in late 2024, but I believe the Commandments still generally hold:

-

- Thou shalt not focus too much on DAC.

- Thou shalt not cast stones at DAC, either.

- Thou shalt emphasize CDR methods with viable revenue streams beyond CDR.

- Thou shalt not rely upon the voluntary carbon market to build a gigaton-scale CDR industry.

- Thou shalt not forget about lifecycle emissions.

- Thou shalt not compare CDR to waste management.

- Thou shalt not mistake CCUS for CDR.

- Honor thy market-pull mechanisms.

- Honor thy subnational policy mechanisms.

- Thou shalt not covet funding for emissions reductions.

My CDR beliefs have evolved over the past nine months, but I wouldn’t change much about this list. If I were to change anything, I’d reword Number 4 and add an 11th one somewhere: CDR is not an industry at all. I’m highly confident in this statement for several reasons:

-

- Lots of CDR methods are only similar to each other in that they each happen to remove CO2from the atmosphere.

- If we consider carbon removal an industry, the failure or scandal of one company could poison the well for other companies that are in no way similar.

- Just as carbon emissions are a negative externality, carbon removals are a positive externality. “Carbon emissions” isn’t an industry, so carbon removal isn’t either.

- Bunching together a variety of seemingly different climate technologies and processes and calling the aggregate an “industry” shines a spotlight on one of the biggest things we don’t want to put in the spotlight: the fact that we’d support projects primarily for their climate benefits to begin with. Whether you like it or not, the economic argument must take precedent.

Individual CDR methods like direct air capture and biochar may be industries, and even MRV may be its own industry, but bundling the entire CDR ecosystem together and acting like it’s a cohesive industry will do us more harm than good. Throughout 2025, I’ve added additional pillars to my CDR philosophy. Here are a few of them:

-

- CDR is not about “degrowth.” The Abundance discussion, spurred by the New York Times bestseller from Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, is a bit too simple, unstructured, and, in my opinion, optimistic. But what Klein and Thompson get right is that we won’t scale low- and negative-emissions infrastructure with the same stringent regulations in place that strangle infrastructure development today.

- CDR can help bolster national security if we want it to . As one example, manufacturing negative-emission materials may allow us to build a domestic circular economy and reduce our reliance upon imports. As another example, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) can remove CO2 from the atmosphere and provide baseload power to the grid, all the while supporting local feedstock providers and decoupling the domestic economy from global supply chains.

- There are no silver bullets in addressing climate change. Within the world of carbon removal, perhaps the biggest violation here comes from unrelenting proponents of ocean iron fertilization. When we give any solution the silver bullet treatment, we implicitly decide that its benefits outweigh its risks. Sometimes, I fear we lose the forest for the trees. Or in the case of OIF, I guess we lose the algae bloom for the plankton.

One of the most rewarding parts of writing Renaissance Carbon is learning lessons like these. I’ll continue writing Renaissance Carbon, which I’ve recently expanded to cover a broader range of carbon-related topics than just carbon removal. This publication with the Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal, however, will focus exclusively on CDR.

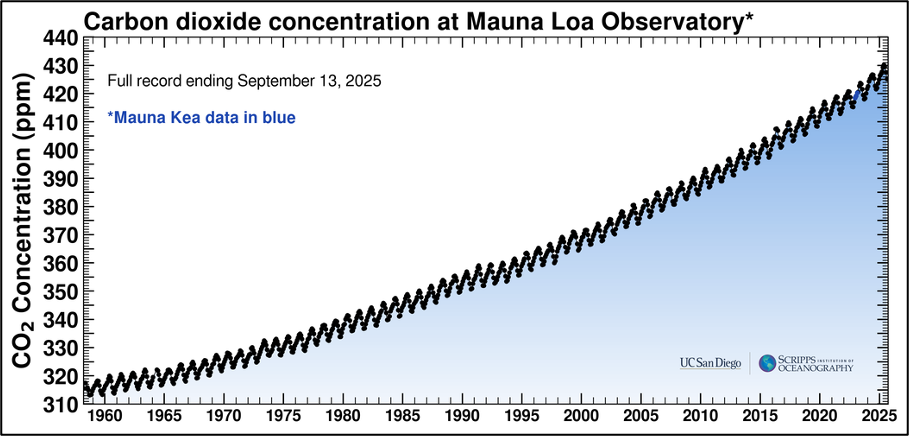

I thought for a while about what to call this publication. I decided on “Keeling’s Descent” because that’s exactly the long-term goal of the CDR ecosystem: to not only flatten the Keeling Curve, but to force it downward. Before the Industrial Revolution, atmospheric CO2 levels sat at around 280 parts per million (ppm). Now they’re at 424 ppm, representing a human-caused increase of 51 percent. Don’t get me wrong; we’re much more than 51 percent better off now than we were before the Industrial Revolution. But at some point, our increased well-being will plateau while emissions and their associated negative impacts continue to expand. Given the quantum leaps we’ve seen in clean energy technologies over the past couple of decades, I’m inclined to believe that point is now.

Achieving net-zero emissions globally by 2050 would imply that the curve will flatten out within the next 25 years. I hate to say it, but this feels like a pipedream. The curve won’t trend downward for a very long time; I’d give it at least three decades, and even that might be aggressively optimistic. I am optimistic that it will someday happen, though.

On this note, I’ll offer a disclaimer. I’m not going to use this platform to paint a rosy picture of the future or push crackpot proposals that will magically help us remove 10 billion tons of CO2 from the atmosphere each year. I consider myself a climate optimist, but optimism without realism is nothing short of insanity. I may discuss uncomfortable topics, and we will face all too many inconvenient truths in the years to come. One example: Oil and gas companies will play a huge role in scaling CDR. Do they see it as a hall pass to continue producing fossil fuels? Maybe. Do they see it as a way to stay relevant? Absolutely. But does that even matter?

Finally, at the end of each Keeling’s Descent post, I’ll drop the latest CO2 reading from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. In the summer months, this number will fall because the growth of land-based vegetation in the Northern Hemisphere outweighs human-caused CO2 emissions. In the fall, winter, and spring months, this number will rise as biologic sinks (and humanity, of course) release their CO2 back into the atmosphere.

Nobody knows when (or even if) the Keeling Curve will reach an apex.

But when (or if) it does, let’s be ready to pull the curve downward while building our economy upward.

Latest CO2 reading: 423.84 ppm

Ryan Davidson is a business development and policy specialist in the U.S. marine energy sector, and in his free time he writes Renaissance Carbon, a weekly Substack about the tech, politics, and culture of all things carbon. The opinions expressed in Keeling’s Descent are his own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of any employer.

Contact: ryandavidson911@gmail.com