KD #2: A few thoughts on MRV and additionality

It’s an age-old question, and it’s perhaps more philosophical than anything: If a tree falls in the forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

I’ve always argued that it does not. By definition, sound waves need eardrums to hit for them to constitute sounds, as opposed to merely vibrations moving through the air. (Of course, I’m assuming no squirrels, rabbits, chipmunks, or other forest-dwelling, eardrum-possessing creatures are present, either.)

But a newer question, more relevant to our physical world, might be: If a tree grows in the forest and no one is around to measure it, does it capture any carbon?

The answer might not be as straightforward as you think.

Let’s set the stage

Additionality and MRV (monitoring, reporting, and verification) are distinct concepts, but in many ways, they walk hand-in-hand.

According to the World Resources Institute (WRI), a “CDR activity is additional when it can prove that it would not have otherwise happened” without the influence of an organized project and the credit revenues that funded it.

Also according to WRI, MRV is “a process for tracking the outcomes of climate mitigation activities. It includes measurement, reporting, and verification to quantify and transparently share information on the outcomes of a variety of climate actions, as well as ongoing monitoring to ensure that outcomes are maintained over time.” Required to verify the delta between a system’s emissions (or negative emissions) with and without the desired intervention, performing robust MRV is the only way for a developer (or country, or whoever wishes to understand their emissions) to have high confidence – and any evidence – that their intervention has removed as much CO2 from the atmosphere as they said it would.

Without this robust MRV, developers don’t know how much CO2 they’ve removed. Without knowing how much CO2 they’ve removed, they can’t issue carbon credits. Without carbon credits, corporate buyers can’t apply removals to their respective carbon budgets while developers lose the backbones of their capital stacks. Without capital, projects fall apart.

MRV and additionality today are so central to the carbon removal ecosystem that sometimes it feels like we talk about the carbon removal credits more than the carbon removal itself.

Despite what The Guardian says (or, conversely, what it… also says?), carbon credits aren’t going anywhere. I want to be clear on that. However, I do think it’s worth asking: Do we over-index on credits?

How did we actually get here?

Credits and offsets for carbon dioxide, or pollutants in general, are not new. Their history goes back decades:

-

- The U.S. Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 introduced sulfur dioxide and nitrous oxide offset requirements for new and modified industrial facilities.

- The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ran a lead credit trading program from 1982 to 1988 before completing the phaseout of leaded gasoline in 1996.

- The Montreal Protocol set a precedent for international emissions cap-and-trade systems in 1987, specifically for chlorofluorocarbons and other ozone-depleting substances.

- Title IV of the U.S. Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 set a cap on sulfur dioxide emissions and the EPA issued a finite number of tradable allowances.

- Using the Montreal Protocol as a model, the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 set mandatory emissions limitation and reduction commitments for 37 industrialized countries and the E.U. and allowed for carbon credit trading through flexible mechanisms.

- To implement the Kyoto Protocol, the E.U. created an emissions trading system (ETS) in 2003; while prices remained as low as €5 in 2017, prices have since spiked, even briefly surpassing €100 in 2023.

- The Paris Agreement of 2015, and specifically Article 6, opened the door for countries to support carbon reduction and removal projects in other countries and apply those reductions and removals toward their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

It can feel like they haven’t, but the agreements from Montreal, Kyoto, and Paris have definitely spurred environmental progress (as skeptical as many of us tend to be about international environmental agreements).

However, that the storied history of carbon credits may as well be the storied history of carbon credit scandals is news to nobody reading this blog. The fact that there is now an accepted premium on carbon removal credits, as opposed to more conventional offsets for “avoided deforestation,” lends credibility to the still early-stage global carbon removal ecosystem. And even to those not familiar with CDR, this premium shouldn’t come as a shock; while human activity has raised atmospheric CO2 levels by over 50 percent, other gases in the atmosphere still outnumber CO2 by roughly 2,300-to-1. We really are looking for needles in haystacks.

Is the voluntary carbon market the right way to look through those haystacks?

For as much talk as there is about the voluntary carbon market (VCM) and its role in scaling carbon removal, as a whole we are missing a few key points. Marc Roston, senior research scholar at Stanford’s Precourt Institute for Energy, recently went on The Carbon Curve to discuss his paper from April, titled “The Market That Won’t Trade: Fixing Structural Failures in the Spot Market for Carbon Removals.” He offers three core reasons why the VCM fails to function like a typical market:

-

- Alienability, or Original Sin: The VCM inherited from compliance markets the idea that buyers could purchase certificates and retire them. Under a compliance scheme in which certificates are just permission slips to emit, there’s no point in keeping those certificates; they can go back to the regulator. But under a voluntary CDR scheme, credits are supposed to represent ongoing ownership. Retiring those credits absolves the buyer (and more importantly, the developer) from maintaining the project.

- Custody, or the “Hotel California” problem: In commodities markets (or any other market), transferability is key. Much of the value of an asset comes from the ability to move it or sell it to someone else. With CDR, you can store the CO2, but it can never leave its “storage facility.” So, when buying carbon removal, buyers run the risk of not understanding what they own or where their assets are, and they certainly can’t move their assets.

- Fungibility: Other commodities are fungible, but CO2 captured via some engineered method does not have the same storage timeline or reversal risk as CO2 captured via some nature-based method. And because ton-year accounting is a “philosophical exercise” more than anything, Marc offers us this: “If you emit a ton of CO2 in the atmosphere, you have an obligation to remove a ton of CO2. That has nothing to do with discounting, nothing to do with the social cost of carbon. It has everything to do with the confidence with which you defease the liability.”

I agree that we need to fix these three failures of the VCM as it exists today if it is ever going to mature and function as a legitimate market. But I think it’s worth considering whether it’s possible to achieve some level of negative emissions without going through these growing pains.

MRV isn’t exactly free

Within power generation, overall costs tend to balloon when maintenance costs increase. This can happen with newer technologies, like floating offshore wind turbines, and this can happen with older technologies, like aging nuclear plants. In the former case, massive vessels must tow turbines the size of the Eiffel Tower back to port for lengthy maintenance procedures. In the latter case, evolving regulations can force expensive upgrades. Either way, customers bear the costs.

Carbon removal is no different.

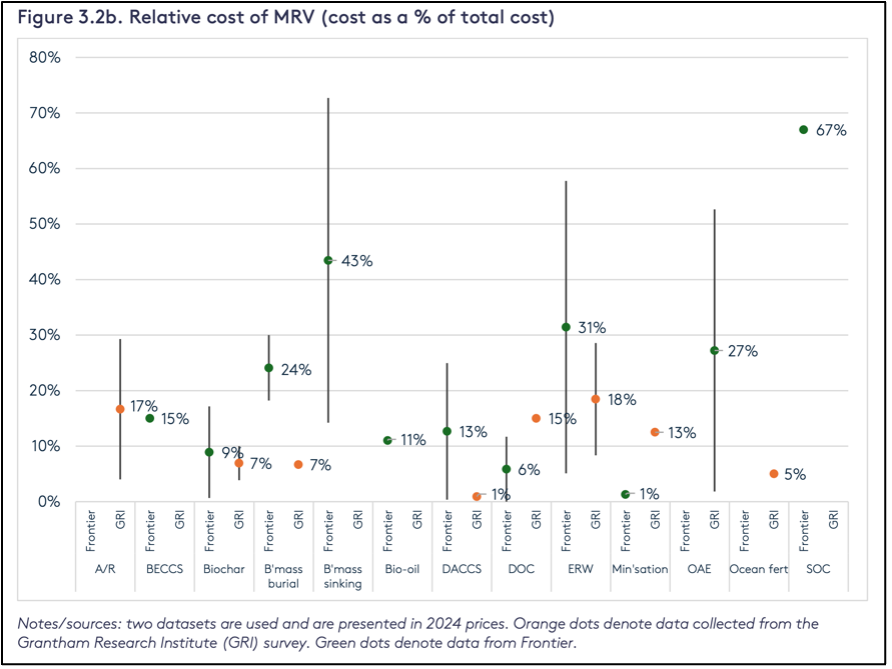

Ongoing operational costs can (and often do) unexpectedly increase, and MRV is a major line item among those costs. For some of the open-system methods, like enhanced rock weathering and ocean alkalinity enhancement, we may someday have a scalable solution to measure CO2-capture at a relatively low cost. Or perhaps we’ll accept some sort of uncertainty range and simply sell the number of credits corresponding with the lower bound of that range to prevent over-crediting. Given that MRV can account for more than half of ERW and OAE project costs, one of these things will simply have to happen if we want to scale these solutions.

I’m a fan of open-system CDR methods not because of their carbon removal attributes, but because of their potentially monetizable side benefits. Let’s say, for example, that we can eliminate enough OPEX and overhead costs in an ERW project for the agricultural benefits to make the project economically viable in its own right. All of a sudden, carbon credits are unnecessary, and the project is by definition not additional. Under our conventional thinking around CDR, this would not be a good thing, because it would no longer be true carbon removal at all. It would simply be the status quo.

But who cares that nobody can take credit for the project? Negative emissions are negative emissions, and that’s really all we should be going for. Just as developers of new technologies should celebrate when their innovations become boring, we should celebrate when carbon removal becomes non-additional… and is therefore not “carbon removal” at all.

A basic thought experiment

This might be an unpopular question, but I’ll ask it anyway. When entities that verify removals, certify credits, or facilitate transactions make up such a large portion of the carbon removal ecosystem, are we even aiming for the right goal? Or better yet: Are we even playing the right game?

An economy-wide crash, or at the very least a dip, is at this point more a question of “when” than “if.” The AI bubble buoying the tech companies (who buy virtually 100 percent of carbon removal credits) will eventually pop, profits will fall, and expenses will have to fall with them. I’d like to say this is just the devil on my shoulder speaking, but it’s not. And when this crash (or dip) happens, will CDR buyers continue to buy? Will they still pay a premium for the permanence and the MRV? I’m no clairvoyant, but I’m pretty confident in my guess.

As crazy as it may seem, the carbon removal ecosystem may do itself a favor by radically rethinking additionality and the associated MRV. This piece is, of course, not comprehensive. It doesn’t detail things like certification, permanence, durability, or leakage, and it doesn’t propose a solution for how we could actually reduce CAPEX to the point at which “side benefits” provide reason enough to invest in a project with negative emissions. I merely hope to propose a basic thought experiment.

So, once more: If a tree grows in the forest and no one is there to measure it, does it capture any carbon?

I’d say it does.

But we’d better coordinate an international protocol to make sure.

Latest CO2 reading: 425.82 ppm

Ryan Davidson is a business development and policy specialist in the U.S. marine energy sector, and in his free time he writes Renaissance Carbon, a weekly Substack about the tech, politics, and culture of all things carbon. The opinions expressed in Keeling’s Descent are his own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of any employer.

Contact: ryandavidson911@gmail.com