How CDR 2.0 may differ from the industry’s first several years

by Jason Grillo

“The impediment to action advances action. What stands in the way becomes the way” -Marcus Aurelius

Well it’s been quite a 12-month news cycle these last few weeks! I don’t want to discuss national or international politics much here, but suffice to say that when Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney in Davos remarks that the international system is in a state of “rupture”, people take note.

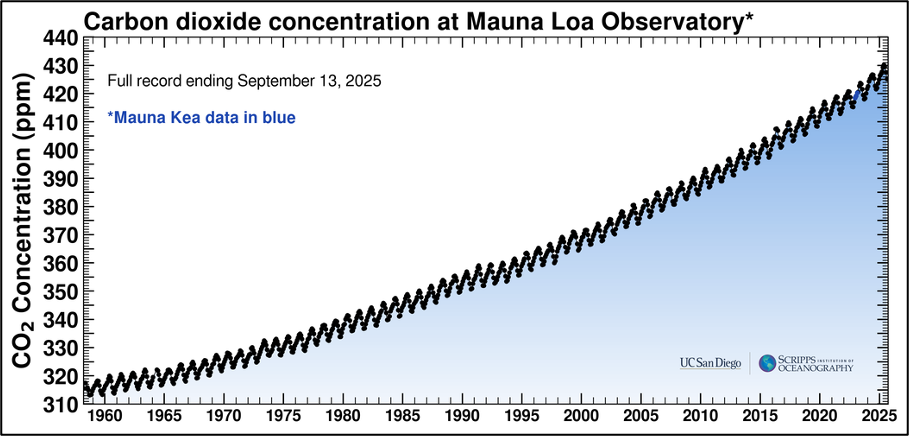

In that backdrop of turmoil, I’d like to discuss what the perhaps bumpy future of carbon removal might look like in the longer time horizon. I’m basing this off the behavior of other industries, past climate peaks and troughs, and my own experiences in the field since I started working in CDR in late 2019.

The Trough

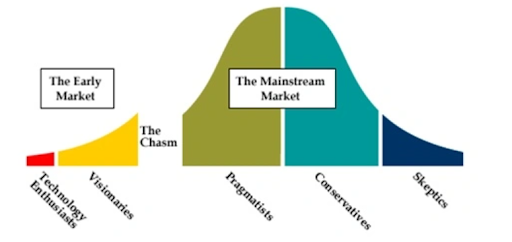

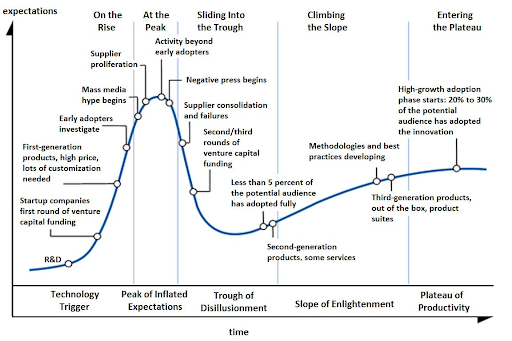

I’ll repeat my assertion in my previous post that per the Gartner ‘hype cycle’ chart, CDR generally is past the ‘peak’, and is just about to begin sliding into the Trough of Disillusionment.

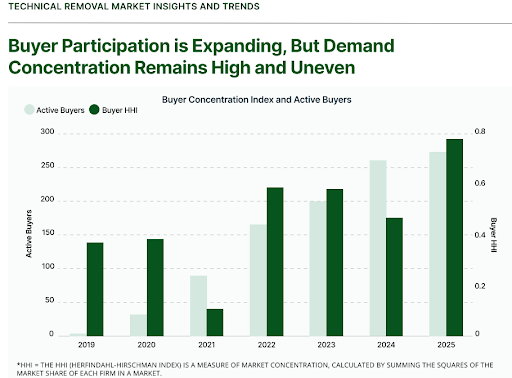

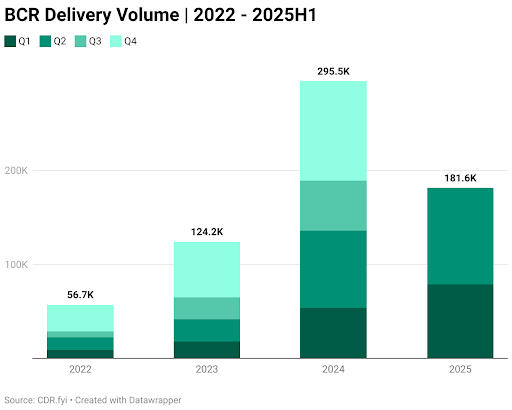

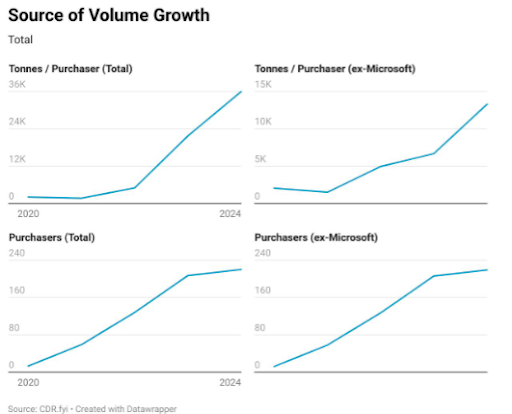

Uncertainty in markets and policy will likely make the next few years a challenging time for carbon removal project developers, who could struggle to achieve funding and product sales. The “less than 5 percent of the potential audience has adopted fully” above, supports the market situation today: the universe of potential buyers has not panned out as expected, with Microsoft still dominant as the world’s biggest CDR buyer – hence this meme here created by the “Carbon Removal Memes” folks.

While the model above suggests venture may offer second or third rounds of funding to some lucky companies, best money may come from other sources of financing: project financing, debt financing, or product revenue. Venture funding in hardware is a tough slog, and may be the same for carbon removal project developers. There is a danger that when venture money is put into hardware projects that ultimately fail, venture may leave the sector altogether – hence the lapse of climate venture funding between Solyndra’s collapse in 2011 and 2019/2020. This would mimic behavior in Cleantech 1.0, where venture funded A123, A Better Place, and (infamously) Solyndra all collapsed (1,2).

In the ‘Trough’ startups may close, early stage funders may not follow on, personnel may leave the CDR industry or depart climate altogether and pursue other interests in different industries.

Open questions: How long will this period last? How deep will it go? And what types of activities will spur a rally?

The Seeds of Recovery

Other industries offer a parallel course to what CDR could see in the 5 to 10 year time horizon. The first internet wave crashed in 2000-2001; Google was founded in 1998 but didn’t IPO until 2003; Facebook was founded in 2003, Apple had its own wild trajectory with, then without, then with, Steve Jobs at the helm. Cleantech 1.0 had its bubble burst around 2011, only to have solar and wind and battery startup survivors grow and develop and outpace expectations. And then we witnessed a wave of a few years of early stage investment starting in the early 2020s, renamed as “Climate Tech.”

I predict a similar model will happen in CDR with crisis, rework, and steady robust recovery as a pathway to the future. Several factors are to play into this:

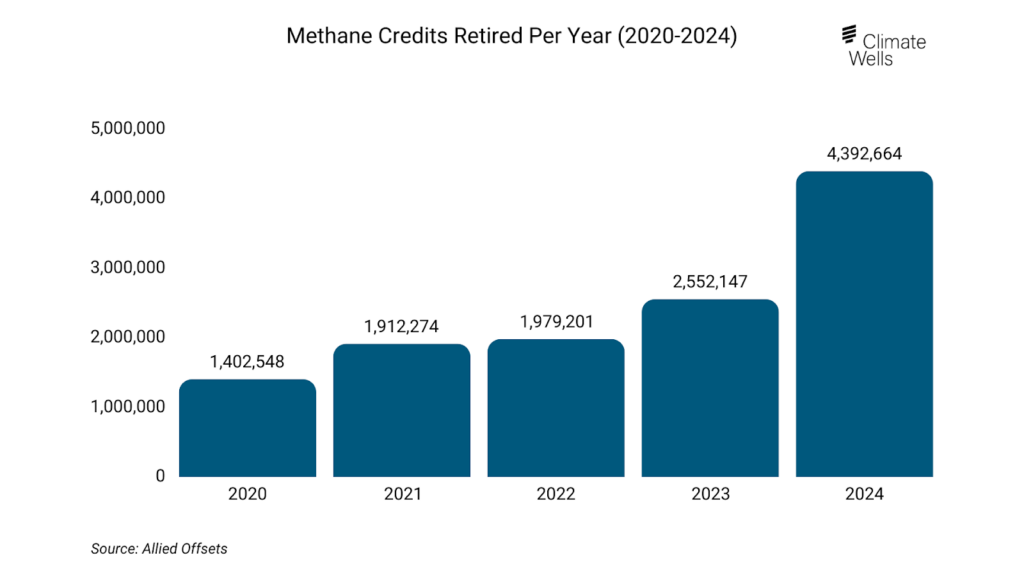

First, CDR 1.0 survivors will carry the industry. Some companies founded before say 2025 will ride out the storm, either by securing the capital they need, achieving commercial success in a challenging market environment, or pivoting to a new business model altogether. Climeworks is pivoting with Climeworks Solutions, offering portfolios of both engineered and nature-based approaches that remove CO₂ from the atmosphere. And Heirloom is partnering with United Airlines to produce Sustainable Aviation Fuel. Biochar deployment in a funding landscape absent venture money can yield physical product for sale with economic value, in addition to delivering CDR credits. That method alone could represent the growth driver for durable CDR credit markets in the next coming years while other CDR methods begin their first commercial deployments.

Here again, Cleantech 1.0 provides a useful analog when wind and solar commercial deployments advanced during the 2011-2019 period between Cleantech 1.0 and Climate Tech 2.0 (roughly). Government support was part of that with German Feed-in tariffs, but the main product – energy – as well as voluntary market Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) provided funding to keep these industries growing. Large, if not industry leading, success stories are also able to weather this type of market adjustment: IBM moved to services rather than primarily manufacturing computers. Yahoo is still alive and kicking. As are Cleantech 1.0 companies First Solar and this Tesla outfit you may have heard a bit about.

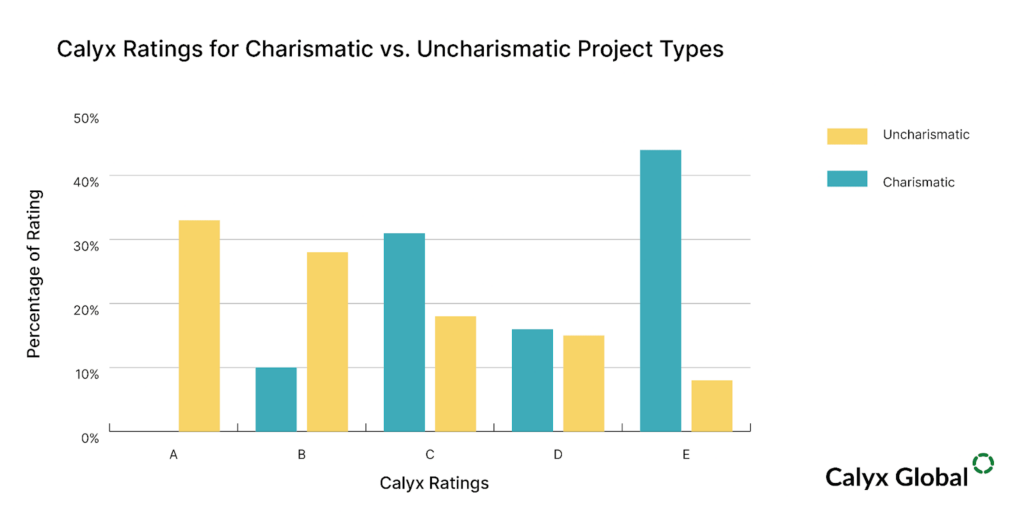

Second, standard consolidation. As of 2026, many, many organizations offer standards for “What Is Quality CDR.” In a new industry, it is natural that that will happen since nobody really has a sense of what “Quality” truly means. The problem is that none are truly comprehensive, and this set of fragmented standards hurts advancement of the field, since outsiders looking in are forced to choose between a multitude of unfamiliar rubrics for comparing projects. This XKCD comic that made the rounds in AirMiners a few years ago best captures this phenomenon. My personal take is that there’s probably room for only a handful of standards relative to the multitude we see today, and that achieving clarity on these will make for a better directed recovery of CDR.

The nature of the standards will depend on what voluntary carbon removal credit buyers want to see. Regardless of whether early catalytic buyers, project developers, and their venture backers believe 1,000 years durability is true “quality,” the mainstream buyers will bear out the case in the market. If say 200 years+ is what becomes the de facto standard, so be it.

That said, the EU’s CRCF voluntary standard for biochar, BECCS, and DAC could be a starting point for this consolidation.

Third, market infrastructure. For one thing, many marketplaces exist for carbon removal credits, each with their own vetting system for who gets in. Buyers have a multitude of channels to choose from, but there are no consolidated exchanges yet.

Contract agreements for purchases are also bespoke; making them more turnkey is the crux of the effort at OSCAR – standardizing contract language to ease friction in carbon removal transactions (3).

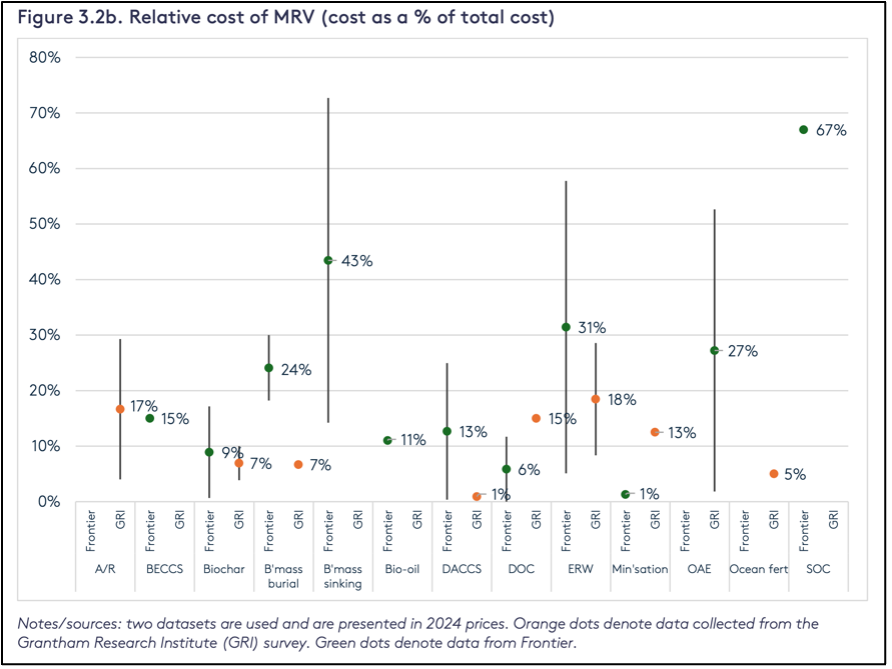

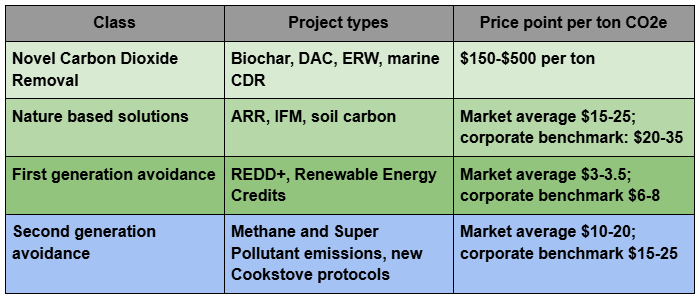

Fourth, price discovery is a key hurdle as well. We are starting to see glimpses of it with broad price bands reported likely due to low numbers of reportable prices in transactions, but nobody can say “ERW is trading at this price”, or (per above) what the 200-year vs 1000 durability price differential may be in a geography of interest. Such clarity may come with greater transaction volume (read: liquidity), but buyers need better price visibility to buy!

A secondary market of trading credits will advance price visibility as well. Right now there is not much of a market trading issued but not retired credits. Deliveries are, by and large, assumed to be retirements rather than tradable.

Fifth, financial innovation can yield a viable path to recovery as well. Consider the potential for CDR to be considered as an asset that can be collateralized, rather than an expense. The work of the Carbon Liabilities and Assets Initiative is particularly interesting in that regard. It removes offsets of any variety from the P&L (which may affect executive compensation and stock price) and instead characterizes credits as an asset to be countered against a liability.

The Rebound: VCM 2.0 and Compliance Markets

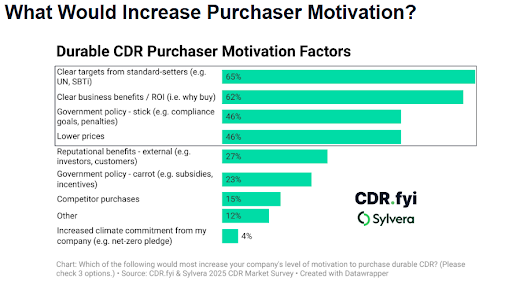

Crucially, policy measures to support CDR – at times taking years of painstaking work – will enable the development of both voluntary and compliance markets.

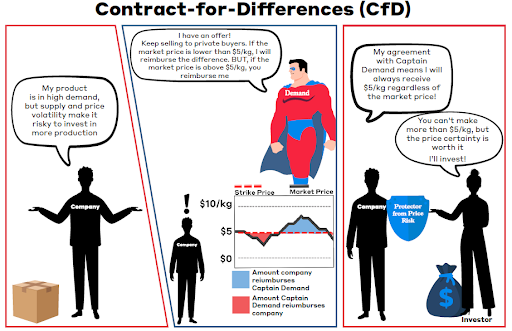

Sylvera estimates that sometime in the next several years, compliance market volume of CO2e will surpass that of voluntary carbon markets. As CDR becomes better integrated into compliance markets, financing for projects may step in to support on the grounds of a more solid customer base (4). I agree with Robert Hoglund’s assertion first that “Carbon removal needs a new story”, and concur with his point that “[f]or compliance, the only real driver for durable carbon removal in the medium term is inclusion into the UK and EU ETS.” We also need to note his caveat that the high price of durable CDR would be too much to be viable in those markets absent Contract for Difference (CfD) government support.

A common theory of change is that anticipating compliance markets will spur voluntary climate action. That way the buyers will grow beyond the courageous few maverick companies who have deep margins to spare. As compliance markets grow and incorporate carbon removal into their schemes, a new round of startups may spring up, spurring technological innovations that rival the monumental work that so many many startup founders to date have put into novel methods to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Carbon removal can also achieve re-emergence through insetting and industrial value chain integration. The entrepreneur of CDR 1.0 may become the intrapreneur of CDR 2.0, working inside a company so that the industrial processes that remove carbon become part of the organization’s value chain. While entrepreneurial in its nature, ‘intrapreneurship’ offers its own challenges, risks, and advantages over a stand-alone startup – more to come on this. As a built-in part of an existing company, CDR can offer some way to solve a general business problem, raise revenue, reduce costs, or acquire customers for a larger business. So carbon removal projects can become a ‘race to the top’ that yield economic benefits rather than being perceived as an add-on cost of doing business.

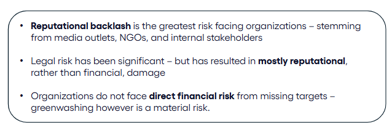

The key risk in the CDR 2.0 world would be policy uncertainty – hence starting this piece off with the term “Rupture.” In a world where international cooperation is weakening, arriving at global standards – or at least a handful of accepted standards – will prove a challenge. The U.N., World Bank, WTO, climate COP and other international bodies could see their power and influence deteriorate, which would diminish the potential for international carbon markets as well. Carbon nationalism may rise as well, where governments assert greater control of the carbon emissions mitigation and sequestration activities within their borders.

Conclusions

Just as the tides wash in and out, the tide of fortune and misfortune cycles through. Such is the way with so many aspects of life; the fledgling durable carbon removal industry will seem no different from others in that regard. While there are significant obstacles in the path of durable carbon removal today, the failures of the market point to pathways for renewal after a time of turbulence. Pragmatism in the near term will lead to flourishing in the longer term.

Finally, my view is that Prime Minister Carney may very well be right about the state of rupture – he got a rare standing ovation from the Davos audience. As a carbon removal community, we would be blind not to listen to the broader context of global uncertainty that coincides with an uncertain time for our industry, and seek opportunities for recovery. I believe a better world will ultimately emerge, whose achievements, both in climate and beyond, dwarf those of the old. It’s a future worth fighting for.

Endnotes:

- Yes, Solyndra received a $535M loan from the DOE in 2009, and additionally had about $1 billion in venture money invested in it as well – see article here from 2011.

- Fun fact: When I was working at a solar inverter company, I actually toured the Solynda factory in Fremont, California…just weeks before the company declared bankruptcy.

- Utterly shameless plug directing you to a recent webinar discussing OSCAR, hosted by the illustrious Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal, American University.

- Biopharma companies are able to IPO without product revenue simply for that reason: customers and health insurers will pay for potentially life-saving and disease-altering therapeutic interventions. See previous Substack on this situation here.

Jason Grillo is the Principal of Earthlight Enterprises marketing and carbon finance consultancy, Co-Founded AirMiners, and is a voluntary contributor to CDR.FYI. The opinions expressed in this writing are the author’s own and do not reflect the position of any employer, client, or associated organization. This post also appears on his Climagination Substack.