Carbon removal prices are going to reflect value to the customer rather than cost of production. Here’s how.

“The purpose of a business is to create a customer … The customer never buys a product. By definition the customer buys the satisfaction of a want. He buys value. … But price is only part of value. There is a whole range of quality considerations which are not expressed in price”

– Peter Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices

One of the questions I hear (frequently!) is “what’s a good price per ton for carbon removal?” Or a variant “What price is carbon removal converging on?” While it sounds like a shrewd question to ask, this assumes that all carbon removal tons are equal – that this is a commoditized market in 2024. Nothing could be further from the case.

My argument in this post is not only that the attributes of projects and methods of carbon removal are highly variable, but that different customer segments perceive different benefits from carbon removal credits. I’m going to suggest a pricing analysis tool below which addresses these customer segment needs from a couple different angles – stay tuned!

But before addressing these customer segments, let’s level-set with some terminology points.

First, Cost vs Price: These are different terms. A ‘Cost’ usually refers to the internal expenses needed for a supplier of a good or service to produce a unit for sale – in this case a voluntary market credit representing one ton of CO2 removed. (FOOTNOTE: Not talking about methane or nitrous oxide equivalents). These take into account labor, cost of the physical resources for production, energy, transportation, and cost of capital.

A ‘Price’ refers to what a producer of a good or service charges to a customer at exchange. The difference between Price charged to the customer, and Cost to the supplier is the Profit margin.

To illustrate, here’s a chart from a conference presentation I recently gave:

Second, Price vs Value: What a supplier charges to a customer for one carbon removal ton is NOT the sum total of the entire value that the customer derives from the purchase. The buyer of a carbon removal ton realizes a value beyond what the market price is that the seller charged for that ton – otherwise they would not have purchased it to begin with.

State of pricing today: A wide variety of value propositions to a customer lead to a wide variation of prices, especially since customers are in 2024 starting to figure out what the value to their organization is of the durable CDR credits purchased.

Indeed, this is exactly what we are seeing in the 2023 State of CDR report (2nd Ed.) prices based on 2023 market conditions:

What price is the “right” price? They all are! Customers are not irrational, even though there is a high degree of variability in these CDR prices. For example, a customer believed that for Direct Ocean Capture CDR $1,402 per ton is a valuable ton to buy: they wanted to see the exchange happen. Another customer believed that for biochar a $131 ton of CDR is a valuable ton to buy. For each of these customers the price was justified by what they used the durable CDR ton to achieve.

Different customers had different rationales underlying their purchasing decision, value propositions, and thus different price points. The reason for purchasing could have been to neutralize Scope 1, 2, or Scope 3 emissions directly, could have been for branding purposes of being perceived as good stewards of the earth, or perhaps to lock in relationships with suppliers for future credits, or simply to signal support for early stage innovation. SBTi’s Beyond Value Chain Mitigation work offers examples of these reasons.

My takeaway: the rationale for purchasing credits drives the perception of value, and thus the price a supplier is able to charge to cover their costs of supporting their business.

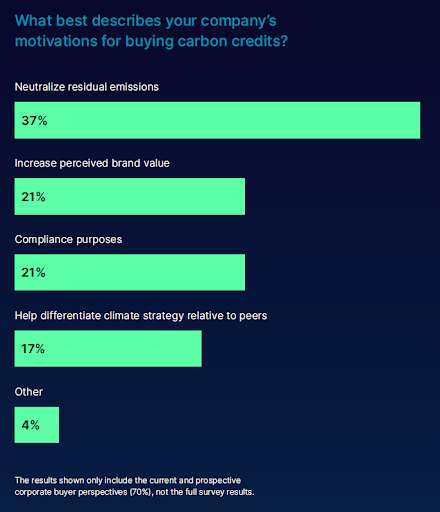

Evidence: These self-reported motivational customer segments are evident in the NASDAQ Global Net Zero Pulse report chart below (Sept 2024):

Granted these are for carbon credit markets writ large – i.e. traditional offsets and less durable nature-based solutions, not only for durable carbon removal – but I would offer that the structure stands, regardless of the type of carbon credit, be it avoidance, less durable CDR (<100 years), or higher durability CDR (>100 years). There is no monolithic rationale for buying durable carbon removal today. When a potential buyer reports that “prices of credits are too high”, the lesson is not that buyers think “you should find a way to lower your costs”, rather “prices are too high for what you are offering to meet what the customer views as valuable now”. The options for a startup to take, therefore, are either:

A) figure out a way to improve the value of the durable CDR credit delivered to the type of customer you are trying to address or

B) Find a different customer who will find what you are delivering to be valuable.

Which leaves carbon removal suppliers at a standstill: if all prices are valid, then what should I charge?

One answer lies in a powerful survey tool that may be helpful: a Van Westendorp model. This technique can yield an acceptable price range for a given set of potential customers.

The four very specific questions asked in Van Westendorp analysis are:

-

-

- At what price would you consider the product to be so inexpensive that you would feel the quality couldn’t be very good?

-

-

-

- At what price would you consider the product to be priced so low that you would feel it’s a bargain?

-

-

-

- At what price would you say the product is starting to get expensive, but you still might consider it?

-

-

-

- At what price would you consider the product to be so expensive that you would not consider buying it?

-

The result, a chart that looks something like this example, with one line tracking each of the four questions, price points on the X-axis, and % of respondents who accept the price for that line description on the Y-axis (e.g. 80% of respondents consider $20 ‘Acceptably cheap’):

And there are several ways of segmenting the data, assuming a large enough set of respondents. For instance, a survey team could segment by industry and see the different ranges represented there. Or ask intake questions (like in the NASDAQ survey example above) to divide up the respondent pool by motivations. Or conduct two sets of questions and change the delivery to be in 2025 vs 2030.

Additionally, you can ask these sets of questions twice, once for lower durability carbon removal, and another time for high durability carbon removal. Charts like the one above would have different price ranges for different purchase types.

This would yield price ranges that offer a quantitative look at how much the value that a customer feels derives into a specific price that a supplier would charge. Then, suppliers would be able to focus on cost targets to become profitable and support their growth – and ability to satisfy the wants of new customers for their products.

The move from cost-based pricing to value-based pricing for CDR credits is just in its infancy, as many early stage technologies are just now starting to move down the internal cost curve. As internal costs decline in future years, startups can drive value by discovering a price point in line with what the customer’s willingness to pay will be, rather than purely to break even on operational costs. Even in the current market, CDR credit supply companies can learn a wealth of knowledge about building a value proposition story that unlocks a customer through offering additional benefits or driving home the message about the quality of carbon removal credits. And in doing so build sustainable businesses that use voluntary carbon markets to drive impact for the customers they serve as well as for the climate.

What do you think? Let me know here

Jason Grillo is a Co-Founder of AirMiners. The opinions expressed in this writing are the author’s own and do not reflect the position of any employer.