The last couple of decades have seen a dramatic transformation of the care infrastructure in South Korea. This is evident from the introductions of successive government policies and programs to socialize care and to address the issue of work-family balance. These new policies and programs have resulted in a steady expansion of publicly funded and publicly or privately provided care services for children and the elderly, financial support for families with young children, and family support programs such as maternity and parental leaves and family care leaves. Although there has been a significant amount of research on child and elder care policies in Korea, not as much attention has been paid to the status of care workers. This is unfortunate particularly given that social care expansion in Korea has been one of the most important drivers of employment growth in the country for the last decade and a half.

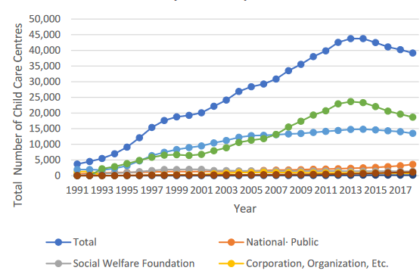

Peng et al (2019) provide an overview of care policies in South Korea and their developments since 2000 and discuss the status of care workers in the context of the current care infrastructure. They focus on paid childcare and elderly care as much of the country’s current care policies are directed to these two sectors. A broad overview outlines the current care policies and systems, including some data on the number of people who are affected and serviced, and some of the immediate causes of the government’s policy focus on care and of social care expansions and reforms. Recent developments in Korea’s care policies illustrate a path of progressive and successful socialization of care that has yielded a significant employment generation, particularly for women. Despite the progress in social care, however, available data suggest that the working conditions and status of care workers in Korea are not very positive: women dominate care work in both child care and elder care, and care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and their employment is precarious. Care work is also accorded with low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress.

The authors conclude by discussing the implications of South Korea’s current care infrastructure for gender equality and the care economy. To better understand the nature of care work and the status and situations of care workers, and Korea’s care infrastructure, they call for more in-depth data collection on care workers as well as more comprehensive measures of care

This paper will be available December 2019