Authors: Rory Jacobson1, Daniel L. Sanchez2

1Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, New Haven, Connecticut, United States

2Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, California, United States

Full citation: Jacobson, R., & Sanchez, D. L. (2019). Opportunities for carbon dioxide removal within the United States Department of Agriculture. Frontiers in Climate, 1, 2.

Abstract: Over the next century, atmospheric carbon dioxide removal (CDR) will be necessary to limit the most significant impacts of catastrophic climate change. Nonetheless, many CDR technologies and land management strategies currently remain at the research and development stage, with minimal capacity for commercialization and deployment. Moreover, farming, ranching, and forestry communities in the United States sit at the front lines of climate change impacts and responses. Fortunately, some of the most inexpensive and promising opportunities for CDR deployment exist within the ability of managed ecosystems, agricultural soils, and forest biomass and products to sequester carbon dioxide. In particular, terrestrial atmospheric carbon dioxide removal (CDR) can reduce the most extreme impacts of climate change while increasing resilience to extreme weather.

Currently, many CDR technologies and land management strategies are still at the research and development (R&D) phase, and lack sufficient federal support to reach widespread deployment. Here, we summarize the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) previous and ongoing efforts to incorporate CDR relevant R&D within their research, education, and economics mission, as well as opportunities to refocus and expand existing programs. Potential future actions to expand CDR R&D capabilities include: 1) the establishment of a new extramural research agency and a new intramural technology commercialization program within USDA, 2) improved coordination between the Foundation for Food and Agriculture (FFAR) and USDA, 3) improved intra-agency and inter-agency coordination, and 4) congressional action to establish and fund new CDR programs within USDA. Finally, we provide an assessment of how changes in funding through legislative actions could support USDA’s leadership on applied RD&D for land-use CDR.

We find that new agencies and programs, such as an Advanced Research Projects Agency for Agriculture and an Agriculture “I-Corps” technology incubator and entrepreneurial training program, could provide breakthrough advances for land-use CDR at relatively low costs. Additionally, we find that many USDA agencies and offices are well suited and equipped to incorporate the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s (NASEM) recommended research programs for carbon sequestration in managed and agricultural lands. In order to implement many of these recommended programs, congressional action will be necessary in order to increase funding to certain agencies or provide explicit direction through appropriations report language. Since all existing USDA programs and agencies are not necessarily well equipped to carry out research on specific land-use CDR research topics, in some cases new programs will also need to be developed in order to execute the recommended research projects. Still, some land-use CDR RD&D activities will require external collaboration or partnerships with existing federal departments or external foundations in order to optimize the effectiveness of USDA research. Specifically, we recommend that for certain projects, USDA should partner and/or more effectively coordinate and collaborate with the Department of Energy and the Foundation for Food and Agriculture.

Nonetheless, we argue that many USDA offices and agencies are well positioned to pursue many land-use CDR R&D projects identified and detailed by NASEM as crucial to scaling and commercializing CDR technologies and land management strategies. Although we find many existing agencies will require some expansion, modification, or increased support, it is evident that USDA will be crucial to, and play a major role in, mitigating emissions from the agricultural sector and increasing carbon sequestration across the United States.

Read Jacobson and Sanchez’s complete paper in Frontiers in Climate.

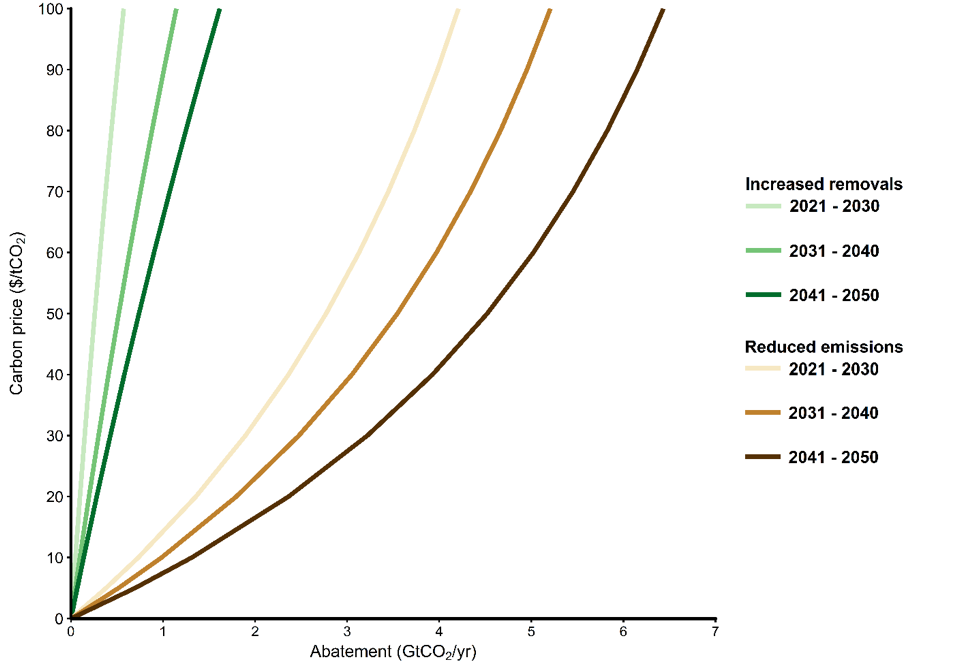

Figure 1. Marginal abatement cost curves for increased removals from tropical reforestation and reduced emissions from avoided deforestation.

Figure 1. Marginal abatement cost curves for increased removals from tropical reforestation and reduced emissions from avoided deforestation.