Why care for all?

— "From the cradle to the grave"

— Demographic transitions (aging in richer countries, high fertility in poorer countries), health transitions, rapid urbanization, increased female labor force participation, and longer schooling are all changing family caregiving

— Care for the caregivers

Care need in 2030 would require the equivalent of 1/5 to 2/5 of the paid labor force.

If all family caregivers were paid, a value equivalent to 16 to 32 percent of GDP per country (King, Randolph, Floro & Suh (2021))

The care burden in families is not equally shared:

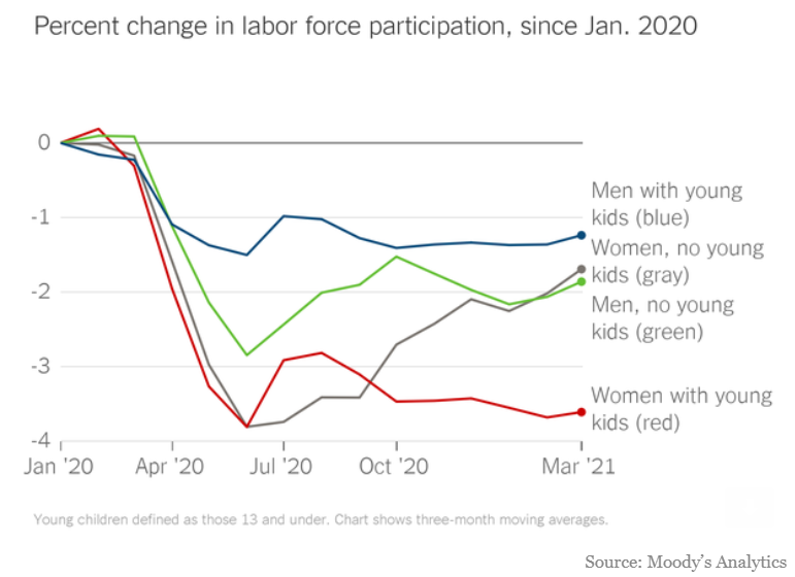

This figure shows the percent change in labor force participation, since January of 2020 and demonstrates the toll of caregiving to caregivers: all groups suffered as a result of the pandemic, but women with young kids (red) have sustained losses in labor force participation.

Measurement and analysis of care burden

— CTMS 2018 household and provider surveys

— Cha (2021) "Determinants Of Paid Elder Care Service Use: Focusing On The Characteristics Of Family Caregiver And Their Household"

— Moon (2021) "The Current Status And Alternatives Of Male Care Participation In Korea"

— Kim (2021) "Policy Recommendations For A High Road To Care In Korea"

— Jun, King, & Kang (2021) "Care Needs Care: Care Needs For Family Caregivers Of The Elderly"

— Peng & Jun (2021) "Impacts Of COVID-19 On Work-Family Balance In South Korea"

— Cha & Moon (2020) "A Glimpse of the Context of Family Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care"

— Friar (2021) "Caring About Influence: Analyzing Relationships and Networks to Promote Effective Advocacy on Care"

— Jun & King (2020); Hensly, Jun & King (2021) "The toll and reward of family caregiving: Eldercare in South Korea"

— Time-use survey data, combined with household survey data; domestic and paid caregivers, ability to distinguish between paid and unpaid services rendered

— King, Randolph, & Suh (2021) "Who cares and who shares? Caregiving in the household"

— Meurs, Tribin Floro, & Lefebvre (2020) "Prospects for Gender-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling for Policy Analysis in Colombia: Integrating the Care Economy"

— Donehower & Kye (2021) "Care Support Ratios in Korea and the US"

— Suh, King, Floro & Meurs (2021)

— Macroeconomic models

— Lofgren, Kim & Fontana (2020) "A Gendered Social Accounting Matrix for South Korea"

— Meurs, Tribin Floro, & Lefebvre (2020) "Prospects for Gender-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling for Policy Analysis in Colombia: Integrating the Care Economy"

Individuals, families, & communities

"Unpaid caregiving, including child and elder care, care for ill or disabled family members, and household tasks such as cooking and cleaning, is a significant household activity in all countries, yet policies related to employment promotion and poverty reduction are often made without considering the impact of such activities. The still-prevailing belief is that care work is primarily a family duty and responsibility and of little direct relevance to economic development. This neglect ignores the realities that households face: the unequal burden of care withinhouseholds, the impact on girls and women who bear the brunt of that burden, and the limited capability of low-resource households to provide adequate care for their members. Unpaid care work is critical, but remains “invisible."

The COVID-19 pandemic has put a spotlight on unpaid caregiving in the home. When public and private services are shut down or incapacitated, the ability of household members to care for one another becomes our sole option for comfort and even survival. Understanding the magnitude of future care need is a first step in planning for adequate caregiving in countries and for ensuring that that need is met." [King, Randolph, Floro and Suh, 2021]

Topics covered by the research

- Understanding the burden of family caregiving: who cares, who shares

- Forecasting future demand for care

- Psychic/mental, physical & opportunity costs and the quality of life of caregivers

- Role of social and gender norms, relative to market incentives and policies

- Access to affordable, good-quality paid caregiving

Project Research

Miller & Bairoliya (2020) "Parental Caregiving and Household Power Dynamics": Paper | Policy Brief

Kang, Eun, & Jun (2021) "Care Arrangement and Caregiving Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare": Paper | Policy Brief

Suh (2021) "Estimating the Unpaid Care Sector in South Korea": Paper | Policy Brief

Gonzalez Garcia, Seo, & Floro (2020) "Norms, Gender Wage Gap, and Long-Term Care"

Moon & Cha (2021) "Family Caregivers' Elder Care: Understanding Their Hard Time and Care Burden"

Hensly, Jun & King (2021) "The Toll and Reward of Family Caregiving: Eldercare in South Korea"

Cha, Kang, & Floro (2021) "Perceived Unmet Demand for Care in South Korea"

Donehower & Kye (2021) "Care Support Ratios in Korea and the US"

King, Randolph, & Suh (2021) "Who Cares and Who shares? Caregiving in the Household"

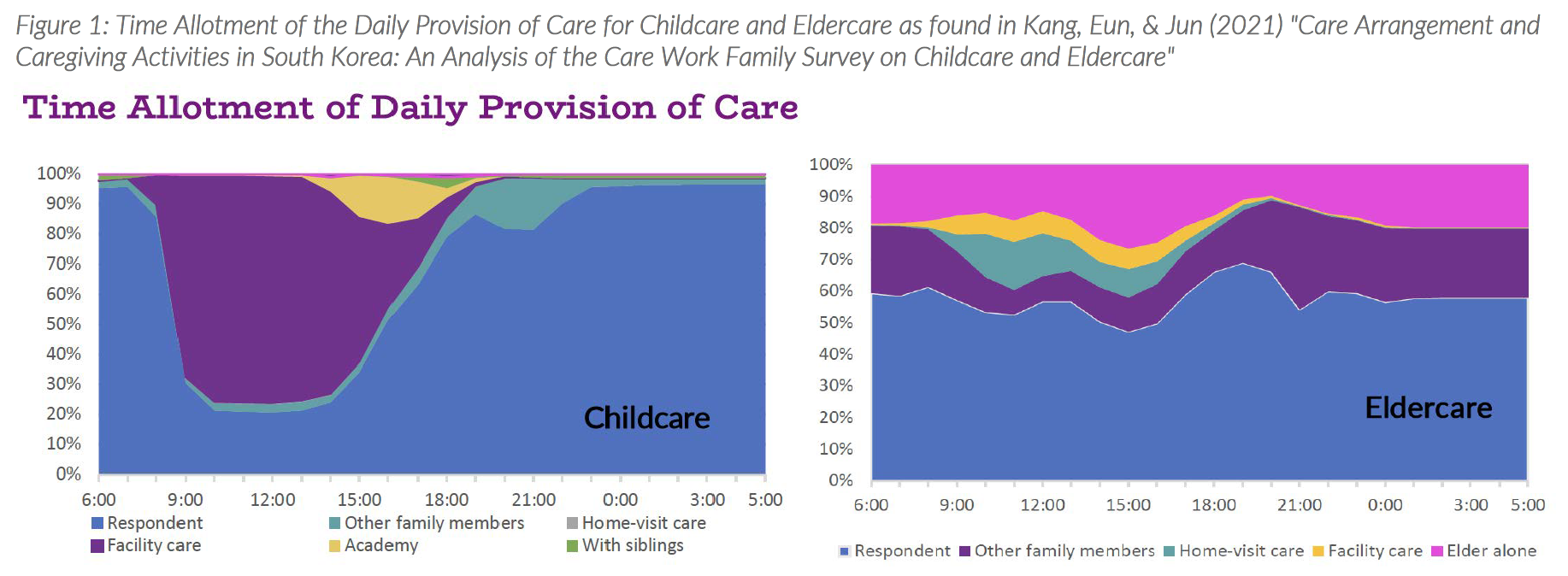

Figure 1 shows the "majority of children are enrolled in facility-based care during the day, but this proportion starts to fall drastically after 3 pm and with a replacement of care by mothers. Likewise, eldercare is concentrated on a primary caregiver in a family. There is a need for public efforts to enhance the equitable share of care works among family members."

Figure 1 can be found in the policy brief for Kang, Eun, & Jun (2021) "Care Arrangement and Caregiving Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare"

Paid Care Service Workers

“Most paid care workers are women, frequently migrant workers, and work in the informal economy under poor conditions and for low pay. Paid care work, in particular home-based paid care work, is a rapidly growing field in South Korea and across the globe and will remain an important source of employment, especially for women, in decades to come. Yet this burgeoning workforce is nearly invisible, many of whose members are laboring out of sight in private homes.” - Suh (2020)

Topics covered by the research

- Quality home-based and center-based caregivers

- Advocacy for rights of caregivers

- Training of caregivers

- Information-sharing among caregivers

- Fair compensation and worker protection, especially for migrant workers

Project Research

Suh (2020) "Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea": Paper | Policy Brief

Peng, Cha, & Moon (2021) "An Overview of Care Policies and the Status of Care Workers in South Korea"

Arslan, Floro, & Alam (2021) "Care Workers' Commitment, Work Intensity and Job Quality"

Friar (2021) "Caring About Influence: Analyzing Relationships and Networks to Promote Effective Advocacy on Care"

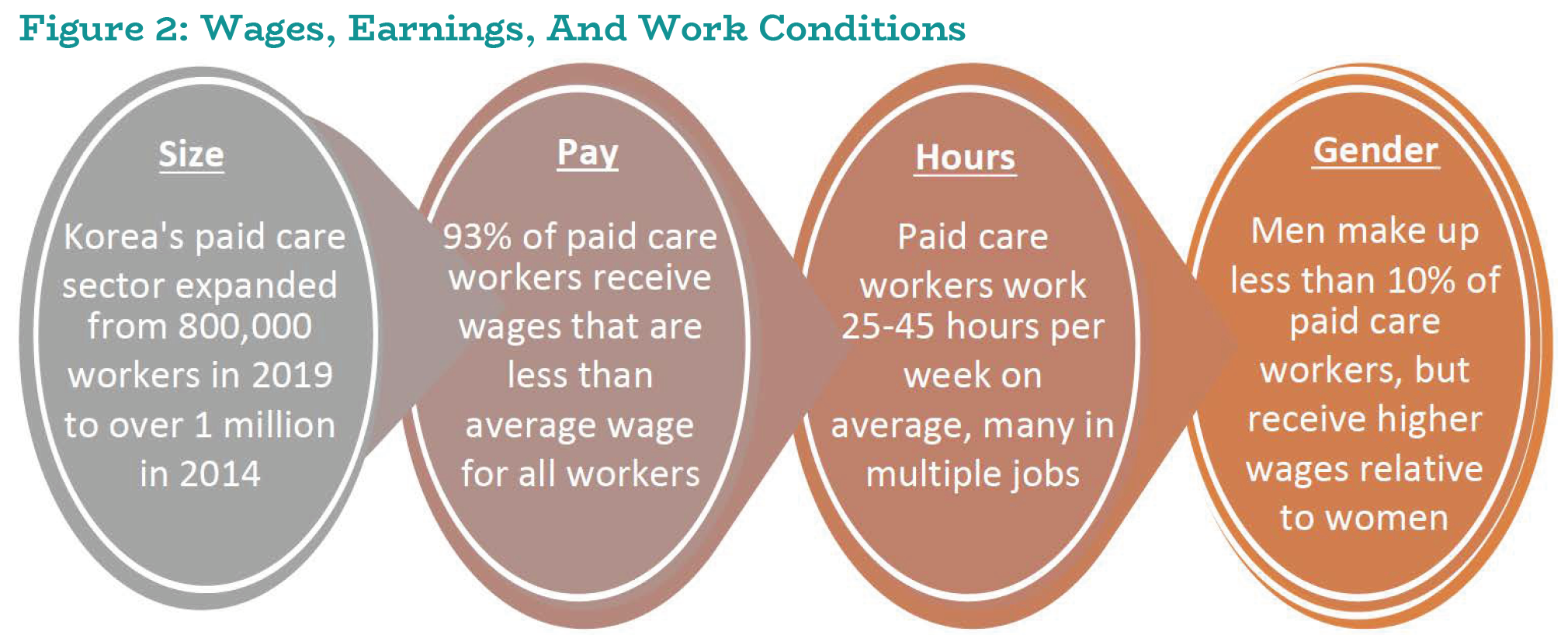

Figure 2 shows information about the wages, earnings, and work conditions of paid care workers in South Korea as found in Suh (2020) "Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea"

"Paid care workers face poor conditions, long hours, and low pay. These adversities are more extreme in the case of migrant paid care workers. Female workers are paid less than men, despite forming over 90% of the paid care workforce."

Figure 2 can be found in the policy brief for Suh (2020) "Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea"

Private Sector Employees

Research highlights the collective benefits able to be gained if employers were to provide more generous, appropriate work benefits such as maternity or family leave, sick leave, health insurance plans, pension plans, and more reasonable and flexible work hours. Work practices—i.e. nondiscriminatory recruitment and promotion practices for people with such care needs—similarly must be care sensitive to provide maximal benefit.

"Simultaneous access to care services as well as new job opportunities transform the gender gaps in employment, earnings, time allocation, time poverty and income poverty… Access to ECEC [early childhood education and care] services facilitates a notable reduction of the of the gender gap but stops short of eliminating it. Hence policy interventions for gender parity need to go beyond giving access to jobs and services, to entail more comprehensive interventions, such as labor market regulation for work-life balance with equal gender incentives and better working conditions." (Ilkkaracan, Kim, Masterson, Memis, and Levy, 2020)

Topics covered by the research

- Direct care services (e.g. daycare at work)

- Work benefits (e.g., maternity/family leave; health insurance; pension plan)

- Nondiscriminatory recruitment and promotion practices

Project Research

Ilkkaracan, Kim, Masterson, & Memis (2020) "Impact of Policy Interventions at Reduction and Redistribution of Unpaid Care Work On Employment Generation, Time- And Income-Poverty And Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation For Turkey": Paper | Policy Brief

Braunstein & Tavani (2020) "Gender Wage Equality and Investment in Care: Modeling Equity and Production"

Peng & Jun (2021) "Impacts of COVID-19 on Work-Family Balance in South Korea: Empirical Findings and Policy Implications"

Ilkkaracan & Memis (2021) "Towards a Caring and Gender-Equal Economy in South Korea: How Much Does the Regulation of Labor Market Working Hours Matter"

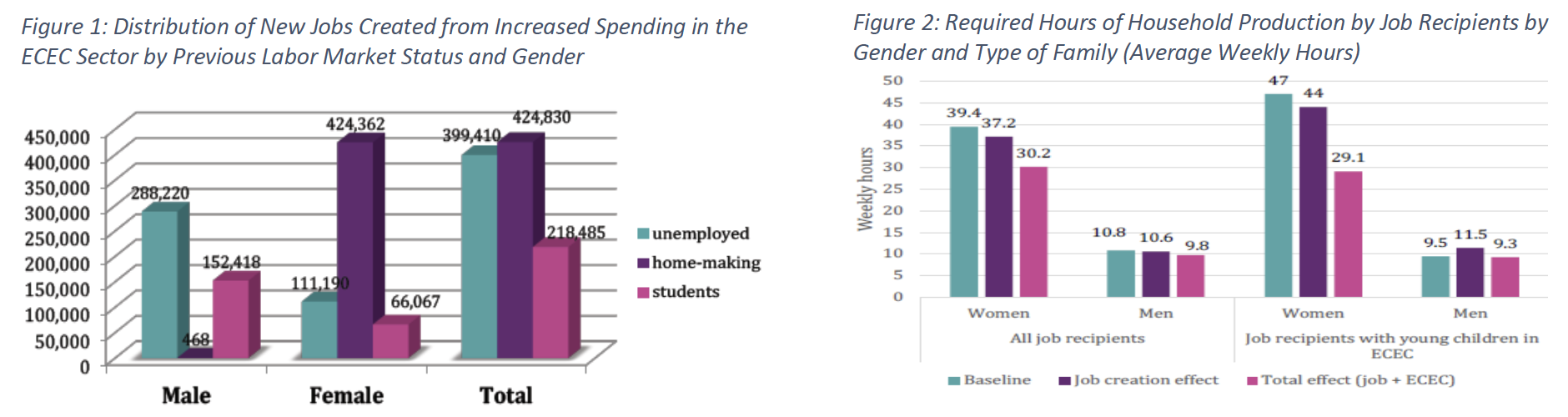

Figure 1 shows the distribution of new jobs created from increasing investment in the early childhood education and care (ECEC) sector: Women previously engaged in full-time homemaking are the main beneficiaries of the new jobs created, about half of whom are mothers of young children.

Figure 2 shows the breakdown, by gender and type of family, in the required hours of household production by job recipients. Expanded ECEC services result in women spending 23% fewer weekly hours on household production. Women with young children spend 38% fewer weekly hours on household production as a result of expanded ECEC services.

Figures 1 and 2 can be found in the policy brief for "Impact of Policy Interventions at Reduction and Redistribution of Unpaid Care Work On Employment Generation, Time- And Income-Poverty And Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation For Turkey"

Government (national and local)

Research highlights the varied roles the government can play in formulating, promoting, facilitating, and enabling the adoption of care policies in the economy. The role of the government as a provider of care services, a financer for care services, and a regulator of private-sector care services is widely studied and highlighted. The government plays a major and critical role in the success of care policies in the economy at all levels.

“The ways in which the varied kinds of infrastructure and services are provided and funded, by whom and for whom, determine whether care policies can contribute to gender equality and mitigate other dimensions of inequality (Sepulveda & Donald, 2014). For example, evidence suggests that the impact of social infrastructure expansion, on the quality of services that are provided as well as employment that is generated, is different if the government provides finance but the supply comes from the private sector, rather than if the public sector directly provides these services (Fontana & Elson, 2014). The design of a gender-aware CGE model should include representation of these differences, for example through a detailed specification of both public and private sectors that provide care.” (Fontana, Byambasuren, and Estrades, 2020)

Topics covered by the research

- Social Care Infrastructure:

- Regulatory policies for quality assurance

- Information about care policies & services

- Direct care services (e.g., public ECD services; robust & equitable health insurance)

- Research in medical & social sciences

- The government's role in expanding the care economy:

- Tax incentives for families & employers

- Labor regulations

- Immigration policy

Project Research

Braunstein, Seguino, & Altringer (2019) "Estimating the Role of Social Reproduction in Economic Growth": Paper | Policy Brief

Vasudevan & Raghavendran (2019) "Microfinance and the Care Economy: Paper | Policy Brief

Onaran, Oyvat, & Fotopoulou (2019) "Gendering Macroeconomic Analysis and Development Policy: A Theoretical Model for Gender Equitable Development": Paper | Policy Brief

Agénor & Agénor (2019) "Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Growth": Paper | Policy Brief

Heintz & Folbre (2019) "Endogenous Growth, Population Dynamics, & Returns to Scale: Long-Run Macroeconomics When Demography Matters": Paper | Policy Brief

Oyvat & Onaran (2020) "The Effect of Public Social Infrastructure & Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The Case of South Korea": Paper | Policy Brief

Lofgren, Kim & Fontana (2020) "A Gendered Social Accounting Matrix for South Korea": Paper | Policy Brief

Fontana, Byambasuren, & Estrades (2020) "Options for Modeling the Distributional Impact of Care Policies Using a General Equilibrium (CGE) Framework": Paper | Policy Brief

Lofgren & Cicowiez (2021) "Child and Elderly Care in South Korea: Policy Analysis with a Gendered, Care-Focused Computable General Equilibrium Model"

Meurs, Tribin Floro, & Lefebvre (2020) "Prospects for Gender-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling for Policy Analysis in Colombia: Integrating the Care Economy"

Kwende (2021) "Financial CGE Model with a Care Sector for Assessment of Pandemic Events in South Korea"

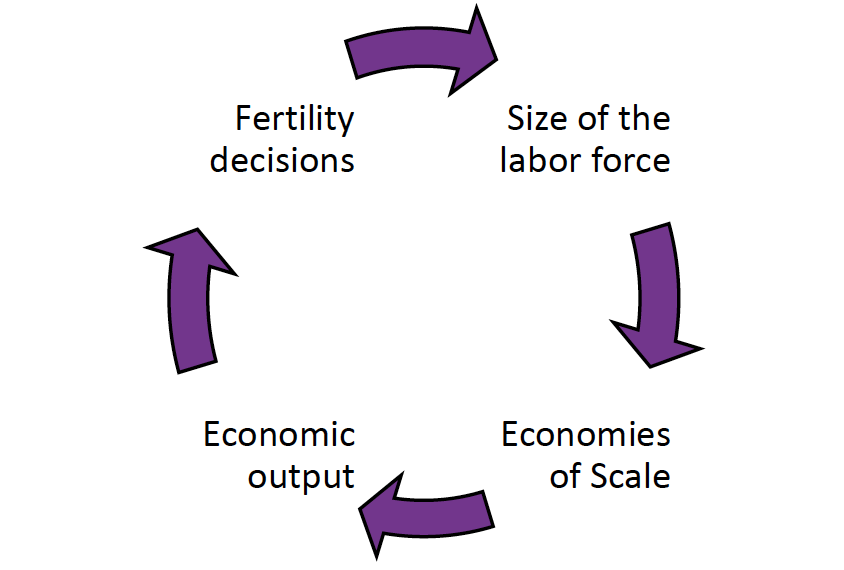

Figure 3 demonstrates "that family size decisions respond to economic conditions and the resulting fertility outcomes collectively drive population growth (or shrinkage)," as found in Heintz & Folbre (2019) "Endogenous Growth, Population Dynamics, and Returns to Scale: Long-run Macroeconomics When Demography Matters"

Figure 3

"The model proposed in this paper considers ways that social institutions, structural features of the economy, and macroeconomic outcomes can influence fertility decisions and so economic growth. A more realistic treatment of demographic dynamics leads to a more realistic picture of macroeconomic trajectories, with important policy implications."

Figure 3 can be found in the policy brief for Heintz & Folbre (2019) "Endogenous Growth, Population Dynamics, and Returns to Scale: Long-run Macroeconomics When Demography Matters"

CWE-GAM Communications Team 2021