The Cost of Caregiving to Caregivers of South Korea

What are the costs of caregiving?

Conventionally, caregiving is considered a household activity that relates to parents raising their infant and young children and adult children taking care of their older parents. Care is broadly categorized into eldercare and childcare but may also include household chores such as cleaning and cooking. There is a dependency between the caregiver and care-receiver, involving both a financial and time cost to the caregiver.

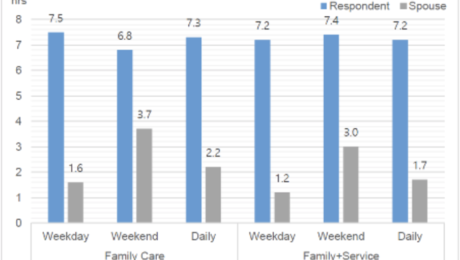

The financial burden of caregiving usually falls on the working age population of an economy. It is the direct cost of caregiving and may include costs to cover basic needs of the dependents such as food, shelter, medical expenses and in some cases, professional supportive care services. Using two nationwide Care Work and Family Surveys on Childcare and Elder care for South Korea, Kang et al (2021) found that on average, a family spends ₩154,000 on supportive care related expenses and ₩179,000 on direct medical expenses. However, a family that hired care services pays ₩132,000 more for supportive care related expenses, than a family that relies only on household unpaid labor. This difference is attributed to higher purchases of expendable medicine and medical appliances (Kang et al. 2021). The higher costs of hired care is offset by a ₩16,000 decrease in direct medical expenses.

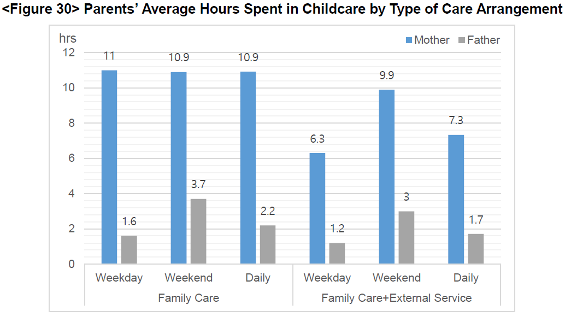

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

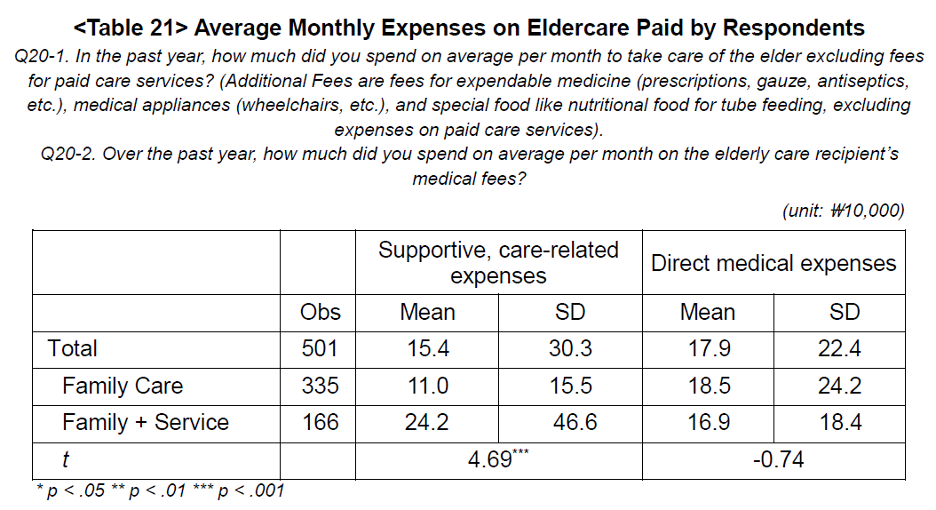

The same study also examined childcare expenses and finds that on average, families spend ₩82,000 on monthly childcare expenses. Here, there are significant cost cutting benefits to hiring paid childcare services. Unlike with eldercare, hiring childcare services decreases monthly childcare expenses for all age brackets. Given the survey question used to measure these expenses, a possible explanation is that service providers supplied these items (baby formula and diapers) and that the payments for such services included these costs.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

In addition, dependents required significant time commitments for labor intensive care activities such as feeding, bathing, and nursing. There is also supervisory care that does not require active caregiving, but is a considerable time commitment, nonetheless. Furthermore, “[t]he still-prevailing belief is that care work is primarily a family duty and responsibility and of little direct relevance to economic development. This neglect ignores the realities that households face: the unequal burden of care within households, the impact on girls and women who bear the brunt of that burden … Unpaid care work is critical, but remains “invisible”” (King, Randolph, Floro, et al. 2020).

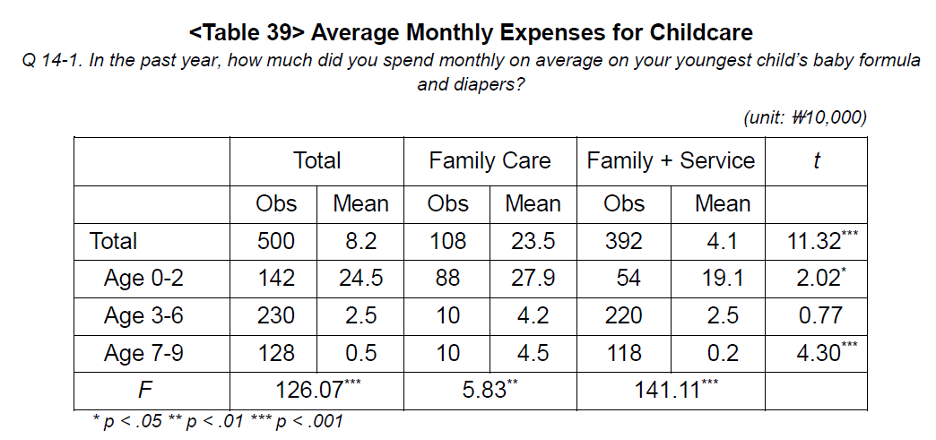

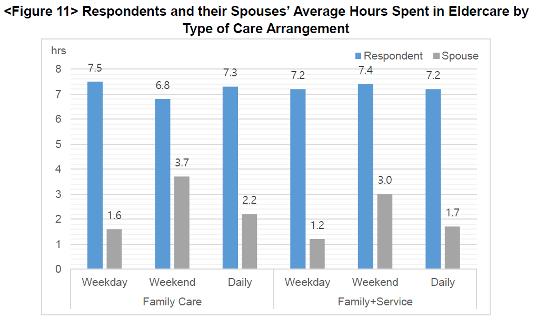

Notes: Respondent in Figure 11 is female.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

These graphs show the gender disparity in the division of care work within the household. On average, women engage in care activities at least twice as long as men, this applies to eldercare and childcare. The graphs also reveal a tendency of hired care relieving men of care duties more than women.

Finally, these time commitments involved an opportunity cost to the caregivers; forgone time and wages.

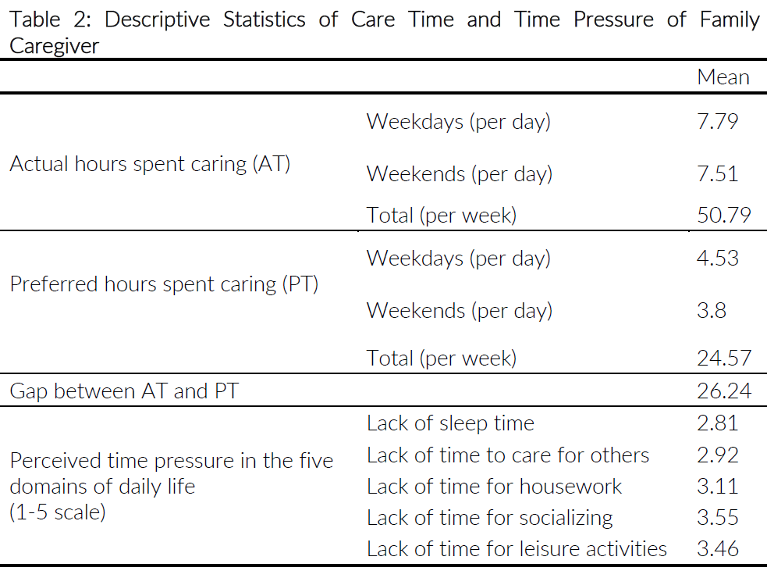

Survey used: 2018 Family Survey for Elder Care

Source: Cha and Moon (2020)

Distinguishing between actual time and preferred time spent in caregiving, Cha and Moon (2020) discovered that on a weekly basis, a household caregiver dedicates a day (26.24 hrs) more than they would prefer to on unpaid care work. The respondents also indicated that there is a lack of time spent in socialization and leisure, which are vital for wellbeing.

Future demand and supply of caregiving.

An aging population, declining fertility rates and a wide gender wage gap implies that the demand for caregiving will continue to exert pressure on South Korean women. “Our estimates clearly illustrate the influence of social norms on the division of labor, the gender allocation of roles and responsibilities, and time use on the potential demand for and supply of caregiving in these countries. They further show that the care burden borne by unpaid household members is quite large relative to the size of the paid labor force, and emphasize that care policies should be a key part of development policy for many countries,” (King, Randolph, Floro, et al. 2020).

This blog was contributed by Praveena Bandara, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha and Moon (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eun, Jun, Cha, and Moon (2021). “Care Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

King, Randolph, Floro, and Suh (2020). “Demographic, Health, and Economic Transitions and the Future Demand for Caregiving.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/6WYH-SS95.

- Published in Care Infrastructure, Child Care, Paid Care Services