The Cost of Caregiving to Caregivers of South Korea

What are the costs of caregiving?

Conventionally, caregiving is considered a household activity that relates to parents raising their infant and young children and adult children taking care of their older parents. Care is broadly categorized into eldercare and childcare but may also include household chores such as cleaning and cooking. There is a dependency between the caregiver and care-receiver, involving both a financial and time cost to the caregiver.

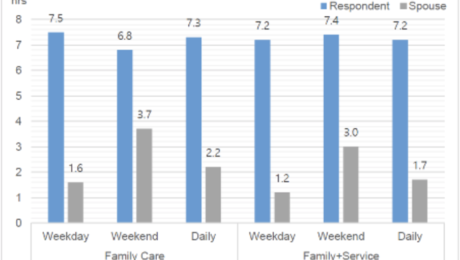

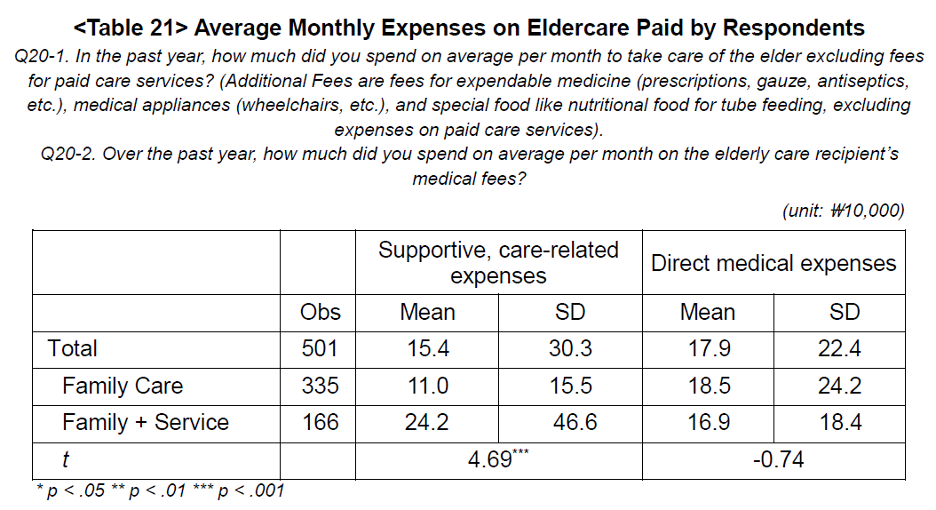

The financial burden of caregiving usually falls on the working age population of an economy. It is the direct cost of caregiving and may include costs to cover basic needs of the dependents such as food, shelter, medical expenses and in some cases, professional supportive care services. Using two nationwide Care Work and Family Surveys on Childcare and Elder care for South Korea, Kang et al (2021) found that on average, a family spends ₩154,000 on supportive care related expenses and ₩179,000 on direct medical expenses. However, a family that hired care services pays ₩132,000 more for supportive care related expenses, than a family that relies only on household unpaid labor. This difference is attributed to higher purchases of expendable medicine and medical appliances (Kang et al. 2021). The higher costs of hired care is offset by a ₩16,000 decrease in direct medical expenses.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

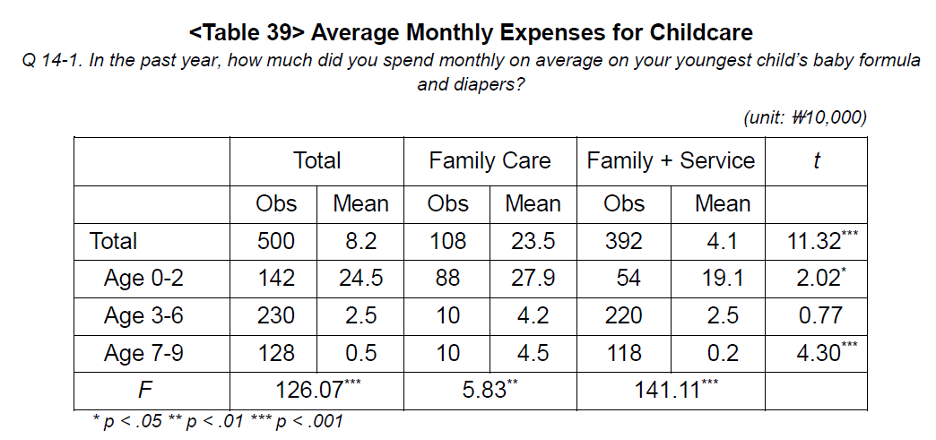

The same study also examined childcare expenses and finds that on average, families spend ₩82,000 on monthly childcare expenses. Here, there are significant cost cutting benefits to hiring paid childcare services. Unlike with eldercare, hiring childcare services decreases monthly childcare expenses for all age brackets. Given the survey question used to measure these expenses, a possible explanation is that service providers supplied these items (baby formula and diapers) and that the payments for such services included these costs.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

In addition, dependents required significant time commitments for labor intensive care activities such as feeding, bathing, and nursing. There is also supervisory care that does not require active caregiving, but is a considerable time commitment, nonetheless. Furthermore, “[t]he still-prevailing belief is that care work is primarily a family duty and responsibility and of little direct relevance to economic development. This neglect ignores the realities that households face: the unequal burden of care within households, the impact on girls and women who bear the brunt of that burden … Unpaid care work is critical, but remains “invisible”” (King, Randolph, Floro, et al. 2020).

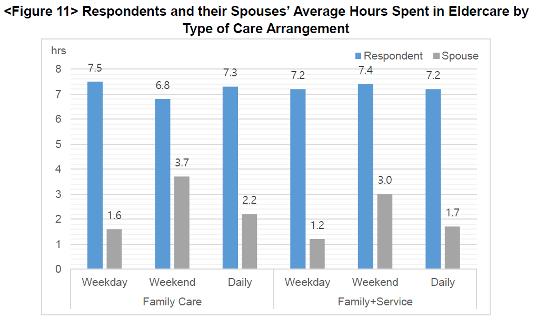

Notes: Respondent in Figure 11 is female.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

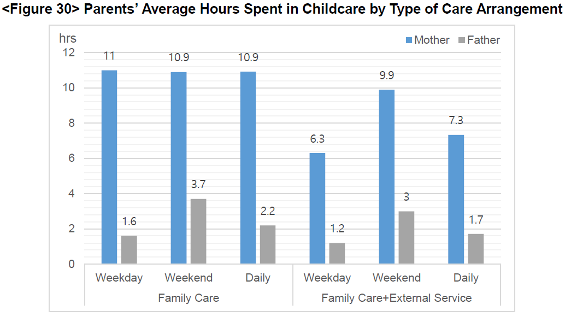

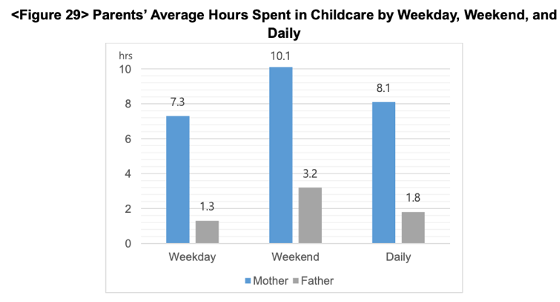

These graphs show the gender disparity in the division of care work within the household. On average, women engage in care activities at least twice as long as men, this applies to eldercare and childcare. The graphs also reveal a tendency of hired care relieving men of care duties more than women.

Finally, these time commitments involved an opportunity cost to the caregivers; forgone time and wages.

Survey used: 2018 Family Survey for Elder Care

Source: Cha and Moon (2020)

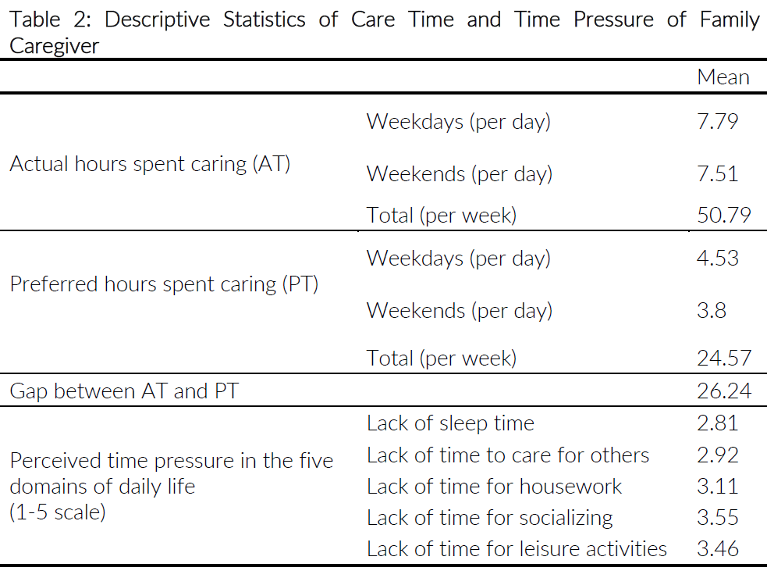

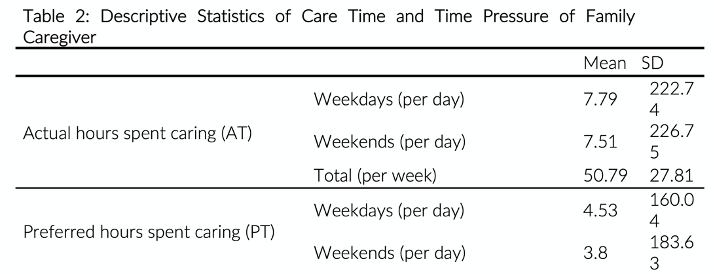

Distinguishing between actual time and preferred time spent in caregiving, Cha and Moon (2020) discovered that on a weekly basis, a household caregiver dedicates a day (26.24 hrs) more than they would prefer to on unpaid care work. The respondents also indicated that there is a lack of time spent in socialization and leisure, which are vital for wellbeing.

Future demand and supply of caregiving.

An aging population, declining fertility rates and a wide gender wage gap implies that the demand for caregiving will continue to exert pressure on South Korean women. “Our estimates clearly illustrate the influence of social norms on the division of labor, the gender allocation of roles and responsibilities, and time use on the potential demand for and supply of caregiving in these countries. They further show that the care burden borne by unpaid household members is quite large relative to the size of the paid labor force, and emphasize that care policies should be a key part of development policy for many countries,” (King, Randolph, Floro, et al. 2020).

This blog was contributed by Praveena Bandara, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha and Moon (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eun, Jun, Cha, and Moon (2021). “Care Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

King, Randolph, Floro, and Suh (2020). “Demographic, Health, and Economic Transitions and the Future Demand for Caregiving.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/6WYH-SS95.

- Published in Care Infrastructure, Child Care, Paid Care Services

Current Situation of Care Work in South Korea: 2018 Family Survey

The Care Work and the Economy project’s 2018 fieldwork in South Korea helped us learn a great deal about how childcare and eldercare is provisioned, both in the paid and unpaid care sectors, in Korea.

The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys, including two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers and unpaid care providers. The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and recipients.

What We Learned about Family Caregiving in Korea

Although many families use at least one external care service to assist with childcare, 22% of respondents reported that their childcare was done only by family members (Kang et al.). Mothers spent six to seven hours more than fathers taking care of children on average.

(Kang et al.)

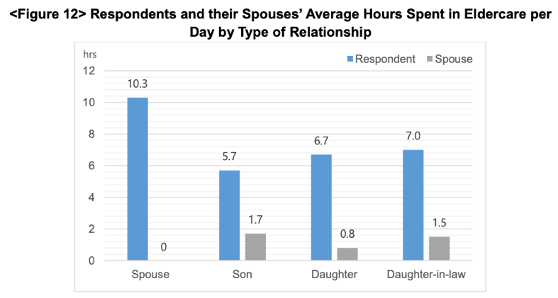

In contrast, 67% of respondents reported that their eldercare was done by family members; the rest reported using external care – usually the national LTC program. The primary caregivers were daughters-in-law (37% of the time), daughters (35%), spouses (15.6%), and sons (11%) (Kang et al.). Figure 12 shows how rather than the elder’s biological children, daughters-in-law provided the most care in terms of time, excepting the elder’s spouse.

(Kang et al.)

The cost of eldercare is shouldered solely by the primary caregiver in many cases (Kang et al., 2021)

Only 20% of family eldercare providers reported receiving regular financial support from other family members, less than 30% reported receiving help on an irregular basis, and only 8% of those over 65 years old were currently receiving LTC insurance program benefits.

Unpaid care provisioning impacts women’s employment.

The surveys showed that “families in which mothers were the sole caregiver for the child had the highest proportion of unemployed mothers, whereas families that received help with childcare from grandparents or paid care service had the highest proportion of employed mothers. With respect to both types of care arrangements, it was mostly daughters and daughters-in-law serving as primary caregiver, almost 70% of whom were unemployed.” (Kang et al.).

When asked about their preferred hours spent caring, eldercare workers reported a considerably lower number of hours on average than the actual hours they spent caring (see Table 2).

(Cha and Moon,2020)

Studies in the CWE-GAM Project stress concerns about the “quality of the caregiver’s life and the care they provide as well as the quality of life of the care recipient. Especially given that women are typically taking on the role of caregiver, this issue cannot be detached from concerns regarding women’s labor, women’s quality of life, and gender equality in Korea.”

Current Situation in Korea – Government Implications:

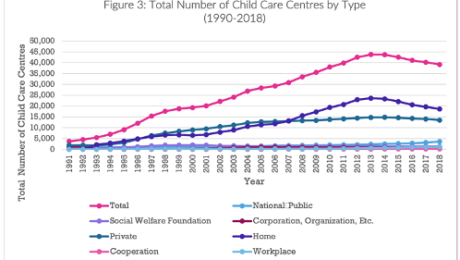

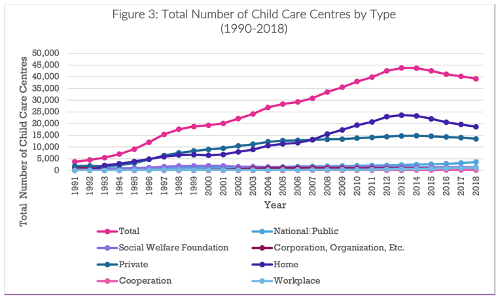

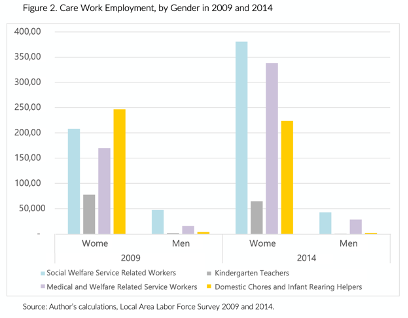

Korea currently “ranks amongst the top 10 OECD countries in terms of public investment in childcare and education” and implemented a mandatory universal LTCI program in 2008 (Peng et al 2021). Figure 2 and 3 show the evolution of child care and care work over time.

(Peng et al. 2021)

(Suh 2020)

Studies report that despite the social care expansion, “childcare and long-term care sectors are heavily dominated by women, and these care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and precariously employed. Care work is also accorded low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress” (Peng et al. 2021; Suh 2020).

Suh (2020) finds that “public investment in quality care services tends to improve the working conditions of care workers (thereby benefiting care recipients), and unregulated private provision tends to worsen them.”

This suggests that “the government and public sector should drive the effort to meet the multi-faceted challenges posed by the growing demand for care work” (Suh 2020).

“The Korean government […] continues to see care work as an extension of women’s unpaid care work and social care expenditure as something that need to be tightly controlled. A better understanding on the part of policymakers about the importance of care and the role of care work and the care economy in generating employment and positive economic growth and supporting a healthy productive economy is therefore necessary.” (Peng et al.)

This blog was contributed by Aina Krupinski Puig, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha, Seung-Eun, and Hyuna Moon. (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family

Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eunhye, Ki-Soo Eun, Jiweon Jun, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “Care

Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

Peng, Ito, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “An Overview of Care Policies and the

Status of Care Workers in South Korea.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/EHN0-R646.

Suh, Joo Yeoun. (2020). “Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea.” Care Work and the

Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/bpdf-v686.

- Published in Child Care, Elder Care, Paid Care Services, Policy, South Korea, Unpaid Care Work