The Care Work and the Economy project’s 2018 fieldwork in South Korea helped us learn a great deal about how childcare and eldercare is provisioned, both in the paid and unpaid care sectors, in Korea.

The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys, including two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers and unpaid care providers. The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and recipients.

What We Learned about Family Caregiving in Korea

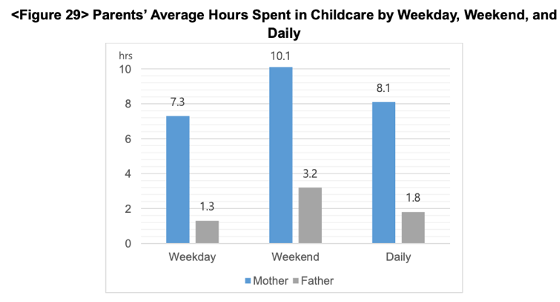

Although many families use at least one external care service to assist with childcare, 22% of respondents reported that their childcare was done only by family members (Kang et al.). Mothers spent six to seven hours more than fathers taking care of children on average.

(Kang et al.)

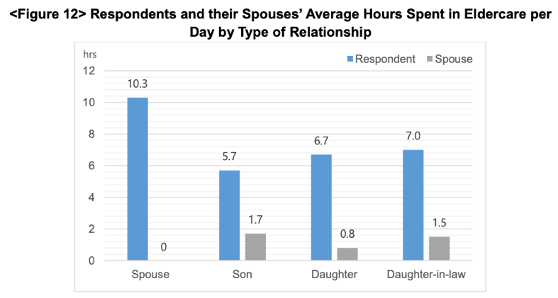

In contrast, 67% of respondents reported that their eldercare was done by family members; the rest reported using external care – usually the national LTC program. The primary caregivers were daughters-in-law (37% of the time), daughters (35%), spouses (15.6%), and sons (11%) (Kang et al.). Figure 12 shows how rather than the elder’s biological children, daughters-in-law provided the most care in terms of time, excepting the elder’s spouse.

(Kang et al.)

The cost of eldercare is shouldered solely by the primary caregiver in many cases (Kang et al., 2021)

Only 20% of family eldercare providers reported receiving regular financial support from other family members, less than 30% reported receiving help on an irregular basis, and only 8% of those over 65 years old were currently receiving LTC insurance program benefits.

Unpaid care provisioning impacts women’s employment.

The surveys showed that “families in which mothers were the sole caregiver for the child had the highest proportion of unemployed mothers, whereas families that received help with childcare from grandparents or paid care service had the highest proportion of employed mothers. With respect to both types of care arrangements, it was mostly daughters and daughters-in-law serving as primary caregiver, almost 70% of whom were unemployed.” (Kang et al.).

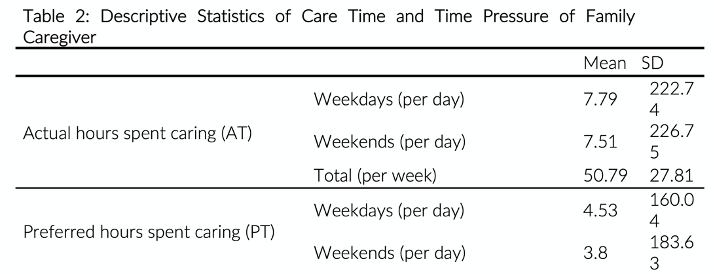

When asked about their preferred hours spent caring, eldercare workers reported a considerably lower number of hours on average than the actual hours they spent caring (see Table 2).

(Cha and Moon,2020)

Studies in the CWE-GAM Project stress concerns about the “quality of the caregiver’s life and the care they provide as well as the quality of life of the care recipient. Especially given that women are typically taking on the role of caregiver, this issue cannot be detached from concerns regarding women’s labor, women’s quality of life, and gender equality in Korea.”

Current Situation in Korea – Government Implications:

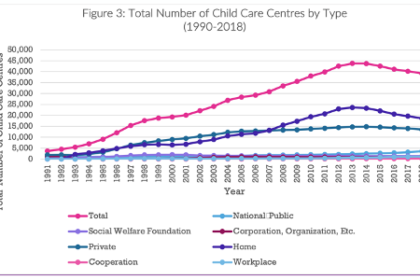

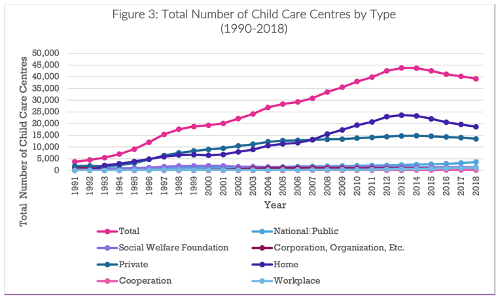

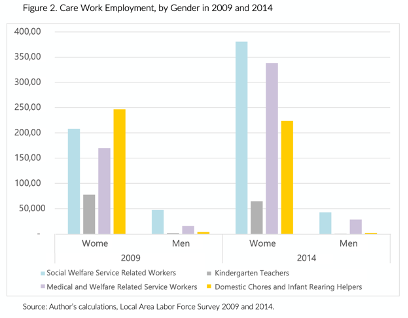

Korea currently “ranks amongst the top 10 OECD countries in terms of public investment in childcare and education” and implemented a mandatory universal LTCI program in 2008 (Peng et al 2021). Figure 2 and 3 show the evolution of child care and care work over time.

(Peng et al. 2021)

(Suh 2020)

Studies report that despite the social care expansion, “childcare and long-term care sectors are heavily dominated by women, and these care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and precariously employed. Care work is also accorded low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress” (Peng et al. 2021; Suh 2020).

Suh (2020) finds that “public investment in quality care services tends to improve the working conditions of care workers (thereby benefiting care recipients), and unregulated private provision tends to worsen them.”

This suggests that “the government and public sector should drive the effort to meet the multi-faceted challenges posed by the growing demand for care work” (Suh 2020).

“The Korean government […] continues to see care work as an extension of women’s unpaid care work and social care expenditure as something that need to be tightly controlled. A better understanding on the part of policymakers about the importance of care and the role of care work and the care economy in generating employment and positive economic growth and supporting a healthy productive economy is therefore necessary.” (Peng et al.)

This blog was contributed by Aina Krupinski Puig, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha, Seung-Eun, and Hyuna Moon. (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family

Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eunhye, Ki-Soo Eun, Jiweon Jun, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “Care

Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

Peng, Ito, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “An Overview of Care Policies and the

Status of Care Workers in South Korea.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/EHN0-R646.

Suh, Joo Yeoun. (2020). “Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea.” Care Work and the

Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/bpdf-v686.