Unmet Demand for Care: Family Caregiver’s Perspectives

Korea faces a care conundrum where the proportion of family care provision for children and the elderly has been consistently large even though the supply of paid care workers has increased over the years. During the first day of the Concluding Annual Meeting, Dr. Seung-Eun Cha, (University of Suwon) presented collaborative research with Eunhye Kang (Seoul National University), Dr. Maria Floro (American University), Shirin Arslan (American University), and Arnob Alam (American University), that questions whether there is an unmet demand for care in South Korea. It also questions whether such an unmet demand results from a preference for family care or because primary household caregivers are unable to utilize outside care resources despite wanting to do so.

The study contrasts the current number of hours primary household caregivers (usually, women – specifically daughters-in-law), spend on care activities with their preferred number of hours they would like to spend on care activities; the premise being that if there is a gap between the actual time and the preferred time, then, there must be an unmet demand for care services.

The study uses data from the 2018 Care Work-Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare in South Korea and studies a sample of 1001 households. Results show that, on average, primary household caregivers spend about 26 and 20 hours more than they prefer each week on eldercare and childcare, respectively. Primary caregivers also reported the number of hours they would prefer their spouse to provide care. Results show that they prefer the spouse to engage in more care work, even if they are currently utilizing paid care services; specifically, around 3 and 7 hours more than they do currently on eldercare and childcare. Low-income groups have a relatively larger unmet demand for eldercare and childcare, while more educated mothers experience a more significant gap for childcare. Furthermore, households in rural areas also showed a larger unmet demand for childcare.

To watch the full presentation, see below.

Written by Praveena Bandara, Research Assistant for the Care Economy Project and PhD student in Economics at American University.

- Published in Child Care, Conferences, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy

The Cost of Caregiving to Caregivers of South Korea

What are the costs of caregiving?

Conventionally, caregiving is considered a household activity that relates to parents raising their infant and young children and adult children taking care of their older parents. Care is broadly categorized into eldercare and childcare but may also include household chores such as cleaning and cooking. There is a dependency between the caregiver and care-receiver, involving both a financial and time cost to the caregiver.

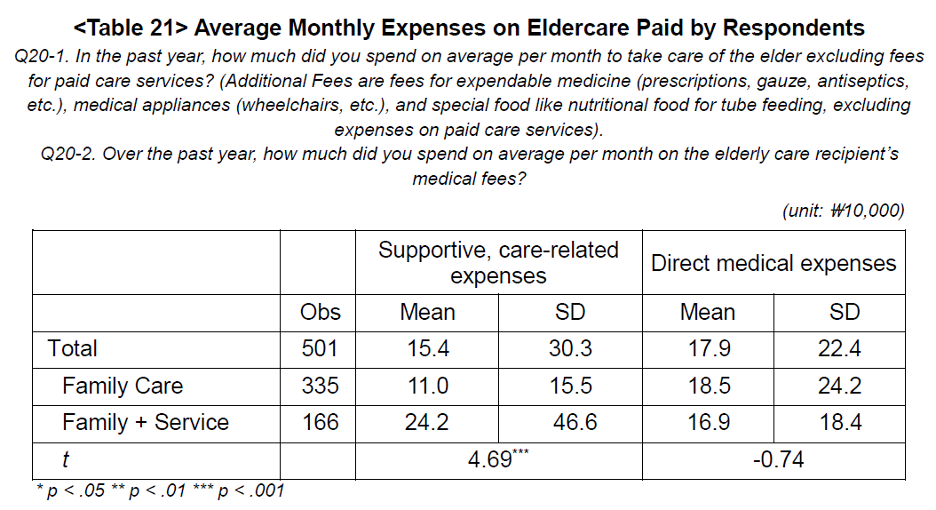

The financial burden of caregiving usually falls on the working age population of an economy. It is the direct cost of caregiving and may include costs to cover basic needs of the dependents such as food, shelter, medical expenses and in some cases, professional supportive care services. Using two nationwide Care Work and Family Surveys on Childcare and Elder care for South Korea, Kang et al (2021) found that on average, a family spends ₩154,000 on supportive care related expenses and ₩179,000 on direct medical expenses. However, a family that hired care services pays ₩132,000 more for supportive care related expenses, than a family that relies only on household unpaid labor. This difference is attributed to higher purchases of expendable medicine and medical appliances (Kang et al. 2021). The higher costs of hired care is offset by a ₩16,000 decrease in direct medical expenses.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

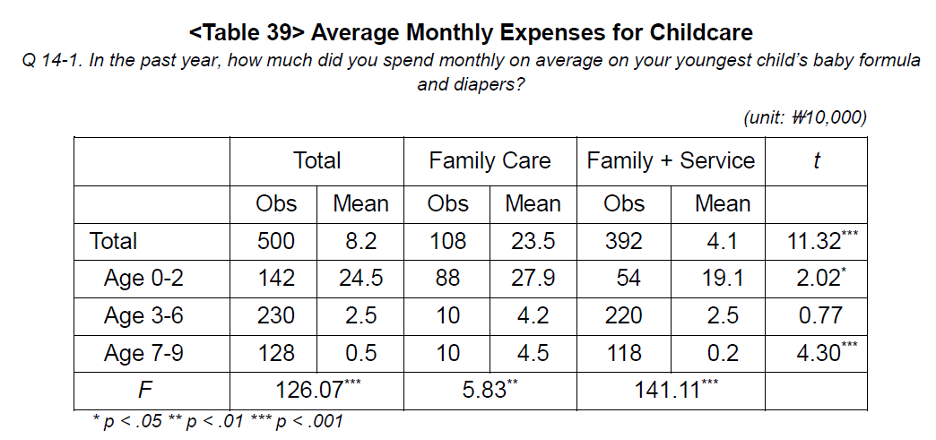

The same study also examined childcare expenses and finds that on average, families spend ₩82,000 on monthly childcare expenses. Here, there are significant cost cutting benefits to hiring paid childcare services. Unlike with eldercare, hiring childcare services decreases monthly childcare expenses for all age brackets. Given the survey question used to measure these expenses, a possible explanation is that service providers supplied these items (baby formula and diapers) and that the payments for such services included these costs.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

In addition, dependents required significant time commitments for labor intensive care activities such as feeding, bathing, and nursing. There is also supervisory care that does not require active caregiving, but is a considerable time commitment, nonetheless. Furthermore, “[t]he still-prevailing belief is that care work is primarily a family duty and responsibility and of little direct relevance to economic development. This neglect ignores the realities that households face: the unequal burden of care within households, the impact on girls and women who bear the brunt of that burden … Unpaid care work is critical, but remains “invisible”” (King, Randolph, Floro, et al. 2020).

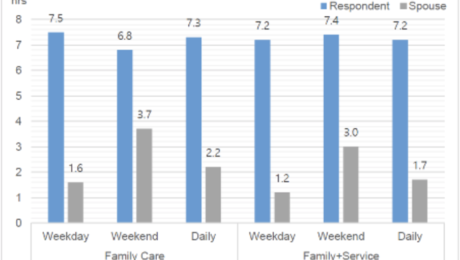

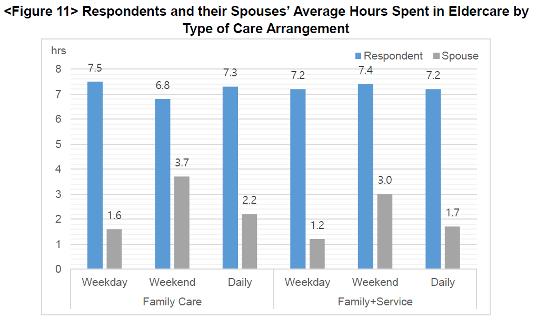

Notes: Respondent in Figure 11 is female.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

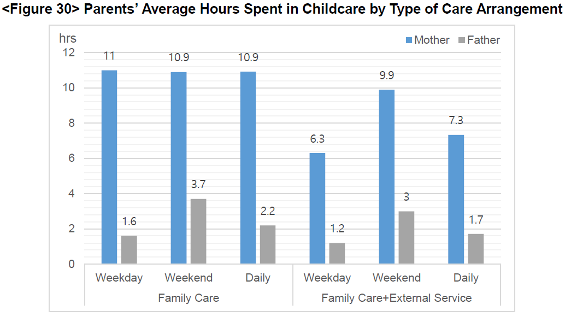

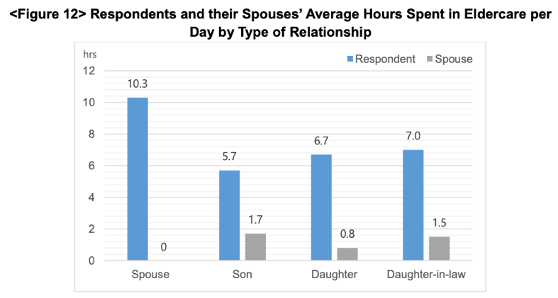

These graphs show the gender disparity in the division of care work within the household. On average, women engage in care activities at least twice as long as men, this applies to eldercare and childcare. The graphs also reveal a tendency of hired care relieving men of care duties more than women.

Finally, these time commitments involved an opportunity cost to the caregivers; forgone time and wages.

Survey used: 2018 Family Survey for Elder Care

Source: Cha and Moon (2020)

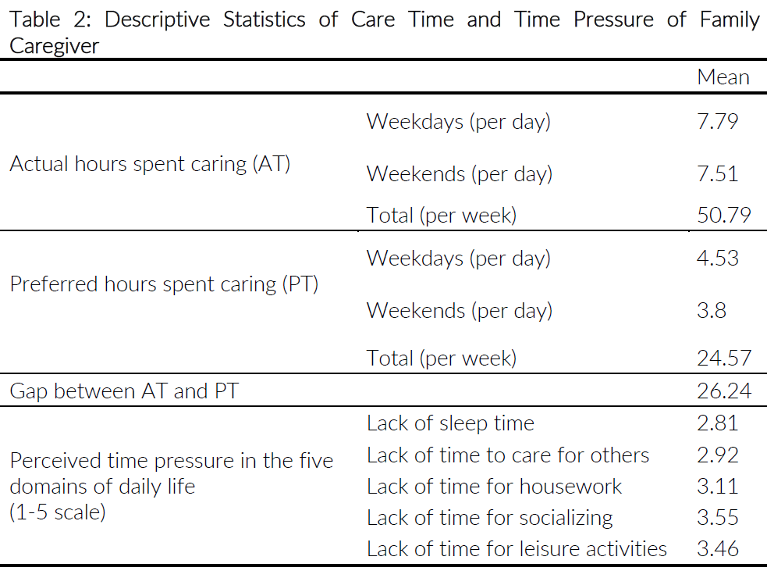

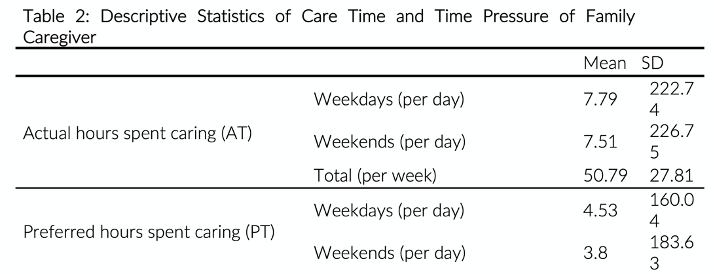

Distinguishing between actual time and preferred time spent in caregiving, Cha and Moon (2020) discovered that on a weekly basis, a household caregiver dedicates a day (26.24 hrs) more than they would prefer to on unpaid care work. The respondents also indicated that there is a lack of time spent in socialization and leisure, which are vital for wellbeing.

Future demand and supply of caregiving.

An aging population, declining fertility rates and a wide gender wage gap implies that the demand for caregiving will continue to exert pressure on South Korean women. “Our estimates clearly illustrate the influence of social norms on the division of labor, the gender allocation of roles and responsibilities, and time use on the potential demand for and supply of caregiving in these countries. They further show that the care burden borne by unpaid household members is quite large relative to the size of the paid labor force, and emphasize that care policies should be a key part of development policy for many countries,” (King, Randolph, Floro, et al. 2020).

This blog was contributed by Praveena Bandara, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha and Moon (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eun, Jun, Cha, and Moon (2021). “Care Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

King, Randolph, Floro, and Suh (2020). “Demographic, Health, and Economic Transitions and the Future Demand for Caregiving.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/6WYH-SS95.

- Published in Care Infrastructure, Child Care, Paid Care Services

Current Situation of Care Work in South Korea: 2018 Family Survey

The Care Work and the Economy project’s 2018 fieldwork in South Korea helped us learn a great deal about how childcare and eldercare is provisioned, both in the paid and unpaid care sectors, in Korea.

The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys, including two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers and unpaid care providers. The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and recipients.

What We Learned about Family Caregiving in Korea

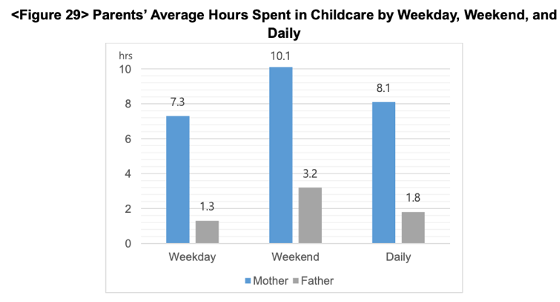

Although many families use at least one external care service to assist with childcare, 22% of respondents reported that their childcare was done only by family members (Kang et al.). Mothers spent six to seven hours more than fathers taking care of children on average.

(Kang et al.)

In contrast, 67% of respondents reported that their eldercare was done by family members; the rest reported using external care – usually the national LTC program. The primary caregivers were daughters-in-law (37% of the time), daughters (35%), spouses (15.6%), and sons (11%) (Kang et al.). Figure 12 shows how rather than the elder’s biological children, daughters-in-law provided the most care in terms of time, excepting the elder’s spouse.

(Kang et al.)

The cost of eldercare is shouldered solely by the primary caregiver in many cases (Kang et al., 2021)

Only 20% of family eldercare providers reported receiving regular financial support from other family members, less than 30% reported receiving help on an irregular basis, and only 8% of those over 65 years old were currently receiving LTC insurance program benefits.

Unpaid care provisioning impacts women’s employment.

The surveys showed that “families in which mothers were the sole caregiver for the child had the highest proportion of unemployed mothers, whereas families that received help with childcare from grandparents or paid care service had the highest proportion of employed mothers. With respect to both types of care arrangements, it was mostly daughters and daughters-in-law serving as primary caregiver, almost 70% of whom were unemployed.” (Kang et al.).

When asked about their preferred hours spent caring, eldercare workers reported a considerably lower number of hours on average than the actual hours they spent caring (see Table 2).

(Cha and Moon,2020)

Studies in the CWE-GAM Project stress concerns about the “quality of the caregiver’s life and the care they provide as well as the quality of life of the care recipient. Especially given that women are typically taking on the role of caregiver, this issue cannot be detached from concerns regarding women’s labor, women’s quality of life, and gender equality in Korea.”

Current Situation in Korea – Government Implications:

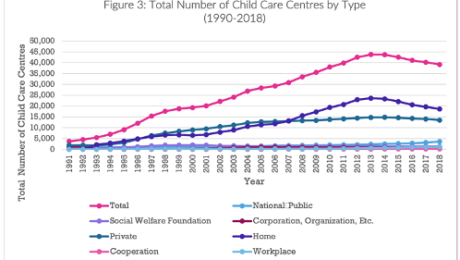

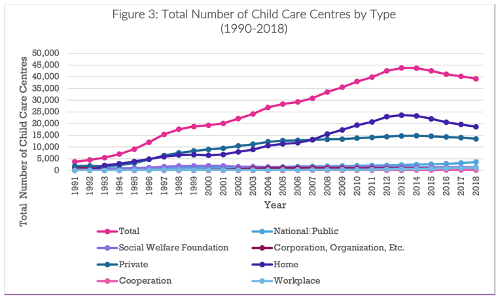

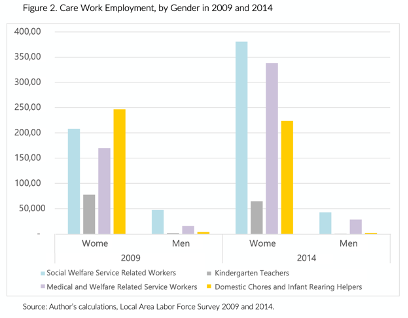

Korea currently “ranks amongst the top 10 OECD countries in terms of public investment in childcare and education” and implemented a mandatory universal LTCI program in 2008 (Peng et al 2021). Figure 2 and 3 show the evolution of child care and care work over time.

(Peng et al. 2021)

(Suh 2020)

Studies report that despite the social care expansion, “childcare and long-term care sectors are heavily dominated by women, and these care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and precariously employed. Care work is also accorded low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress” (Peng et al. 2021; Suh 2020).

Suh (2020) finds that “public investment in quality care services tends to improve the working conditions of care workers (thereby benefiting care recipients), and unregulated private provision tends to worsen them.”

This suggests that “the government and public sector should drive the effort to meet the multi-faceted challenges posed by the growing demand for care work” (Suh 2020).

“The Korean government […] continues to see care work as an extension of women’s unpaid care work and social care expenditure as something that need to be tightly controlled. A better understanding on the part of policymakers about the importance of care and the role of care work and the care economy in generating employment and positive economic growth and supporting a healthy productive economy is therefore necessary.” (Peng et al.)

This blog was contributed by Aina Krupinski Puig, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha, Seung-Eun, and Hyuna Moon. (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family

Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eunhye, Ki-Soo Eun, Jiweon Jun, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “Care

Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

Peng, Ito, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “An Overview of Care Policies and the

Status of Care Workers in South Korea.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/EHN0-R646.

Suh, Joo Yeoun. (2020). “Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea.” Care Work and the

Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/bpdf-v686.

- Published in Child Care, Elder Care, Paid Care Services, Policy, South Korea, Unpaid Care Work

Investing in Quality Care has Positive Macroeconomic Effects

Recent research by Lenore Palladino and Chirag Lala of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts Amherst, examines the effects of critical public investment in childcare, home health care, and paid family and medical leave (PFML) for the U.S. workforce, as proposed by the American Jobs Plan and the American Family Plan by the Biden-Harris Administration.

The authors find that investing in childcare and home health care workforce has positive macroeconomic effects, and the care workforce spends its own money on goods and services through the rest of the economy. They also find that PFML positively boosts the economy, as workers spend the wage replacement income they earn.

The authors model the effects of a $42.5 billion annual investment in childcare and a $40 billion investment in home health care with a minimum wage of $15 an hour and find that the proposed investment can create 564,000 additional jobs throughout the economy, and results in an increase in labor income of $82 billion annually. They find that universal paid family and medical leave, as proposed by the American Families Plan, would increase household income nationally by $28.5 billion, of which $19 billion would be wage replacement directly from the paid leave program, and $9.4 billion would be income earned by workers throughout the economy as people receiving wage replacement spend money on goods and services. This means that for every dollar spent on wage replacement as part of the paid leave program, other workers would earn an additional $.50.

RESEARCH BRIEF: The Economic Effects of Investing in Quality Care Jobs and Paid Family and Medical Leave

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, program manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project.

- Published in Care Infrastructure, Child Care, Elder Care, elderly care, Gender-Equal Economy, Healthcare, Macroeconomics, Policy

“Girly Issues” Are Now the Country’s Issues

Dr. Nancy Folbre, an Advisor and Researcher of the CWE-GAM project and a groundbreaking feminist economist was among the first to sound the alarm about the care crisis. Dr. Folbre’s work on the care sector, once considered “just girly issues” by fellow economists, are now recognized as issues belonging to the U.S.. Previously the recipient of the 1998 MacArthur “genius” grant, Dr. Folbre’s research has journeyed from “fringe idea to more mainstream policy.”

Once cast aside in policy discussions, the care crisis is finally getting the spotlight it deserves after the pandemic forced many schools and child-care centers to close, leaving “ten million mothers of school-age children out of the workforce.” The pandemic is forcing policymakers to finally face the cracks in America’s care infrastructure that Dr. Folbre and other experts have long pointed out— “a system where working parents do not have reliable, affordable child care is one where they cannot reliably build a career.”

To learn more about Dr. Folbre’s work on care, visit her blog Care Talk and read her recent book The Rise and Decline of Patriarchal Systems.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics

Making Care Count

The COVID-19 pandemic has informed our understanding of the care economy, exposing disproportionate inequities that must be addressed to alleviate the international erasure of care workers. These issues are addressed in the latest Susan and Michael J. Angelides Lecture, in which Naomi Klein moderates a discussion between Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal and CWE-GAM researcher Dr. İpek İlkkaracan on COVID-19 and the care economy.

We live in an economic system that has traditionally deprioritized and invisibilized care workers, many of which are women of color, migrant, and poor women. The economic crisis brought on by the pandemic has consequently given policymakers and academics “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address [the valuation of care work] from an intersectional [approach],” states Congresswoman Jayapal.

The Care Crisis Exposed by the Pandemic Recession:

When mass unemployment hit during the pandemic, the cracks in the economic infrastructure of America began to show. As millions of people lost their jobs, the highest increase in the number of uninsured Americans was subsequently recorded. This high number of uninsured people is a direct consequence of healthcare being employer-sponsored. Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “Medicare For All would have strengthened the response to the pandemic…30 percent of COVID-19 deaths were related to a lack of insurance.”

While gains were made in the past decade in regards to gender equality in the workplace, Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “as soon as the pandemic hit, it was the women who went back to taking care of [their] families.” Dr. İpek İlkkaracan explains that this is because “the nature of women’s employment is often determined by their care responsibilities…unpaid care work is often articulated as one of the most significant barriers to labor force participation.” This notion was reflected in jobs reports—in December of 2020, women accounted for 100 percent of job loss, and within that, 154,000 Black women exited the workforce.

In its current state, the care economy produces a pattern of inequality that disproportionately affects women of color and migrant women. The average caregiver salary is $12.74, and the care work sector is marked by poor working conditions with no adequate social protections and low wages. This is why, as Congresswoman Jayapal notes, the fight for one fair wage is pertinent. “An increase in the minimum wage would give 32 million workers a raise, 60 percent of which are women while 1 in 4 of the women who would benefit from this increase are Black or Latina.”

A Framework for a More Caring Economy:

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan has developed a framework that acknowledges the care economy. This framework, coined as the Purple Economy (a nod to the color representative of many women’s movements), envisions a gender-egalitarian and caring economic system. Dr. İlkkaracan recommends “labor market regulations and investment in care services such as long-term care, early childhood education, education, and healthcare” as policy interventions to start the process of adequately valuing care.

Not only is investment in care important from a humanitarian and ethical perspective, but it is also conducive to economic stability. Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has revealed that investment in care services produces a high employment multiplier: for every dollar invested in care, three times as many jobs are created in the wider economy. This is because the care sector is intertwined with other sectors such as food, transport, and financial services. In the Asia-Pacific region, Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has shown that “up to four trillion dollars could be added to GDP if unpaid care work (75% of which done by women) was valued in market terms.” While this may seem astronomical, the amount of unpaid work completed globally in one day equates to 16.4 billion hours—which translates to two billion full-time jobs. Dr. İlkkaracan’s recent research also reveals that a “3.5-4% commitment of GDP to investment in care services would create 120 million additional jobs and have a large impact on poverty alleviation.”

To watch the full conversation and learn more about the Purple Economy, see below.

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan is a CWE-GAM researcher a part of the Rethinking Macroeconomics and Gender Aware Applied Economics Working Groups.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Gender-Equal Economy, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, U.S.

Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective

Below is an excerpt from a recent piece “Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective” by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group. This article was published by Migrants and Systemic Resilience: A Global COVID19 Research and Policy Hub (Mig-Res-Hub).

In this think-piece I consider how we can build a resilient systemic response to the COVID-19 pandemic and future crises. I focus on systemic resilience in relation to carework and global migration of careworkers, and I approach this from an Asia-Pacific perspective. One of the fault lines exposed by the COVID-19 is the vulnerability of the existing care, carework and migration infrastructure to exogenous shocks. Asia-Pacific is an important site to examine because it is one of the major sites of global care migration, both as sender and receiver of migrant careworkers. This think-piece draws on the research from our global partnership project based at the University of Toronto, which looks at the dynamics of careworker migration in Asia-Pacific and the interconnections between social and economic forces and policies in shaping those dynamics from both sending and receiving country perspectives. The next section briefly outlines the pandemic’s impacts on carework and care migration in Asia-Pacific. I then discuss how we might achieve systemic resilience in global care migration by first emphasizing how our care systems are interlocked with the global migration of careworkers (what I call a global care interlock), and second, how we might achieve systemic resilience. Understanding the global care interlock is an important prerequisite to systemic resilience because it allows us to see carework and migration of careworkers as a part of a larger global infrastructure or ecosystem that has been, consciously or unconsciously, built, managed and sustained by multiple actors in different parts of the globe.

Read the entire article here.

This blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing research for the Understanding and Measuring Care research group.

- Published in Asia-Pacific, Child Care, COVID 19, Elder Care, Migrant Care Workers, Understanding and Measuring Care

Biden’s American Jobs Plan Could Be Monumental for the Care Economy in the U.S.

Last month, the Biden administration revealed the details of the $2 trillion American Jobs Plan.

The plan recognizes that investing in the care economy, as with investments in traditional infrastructure, can lift incomes, unleash productivity, and pave the path towards a more equitable economic recovery and growth.

Addressing the care crisis

Built into the plan is a pledge to “solidify the infrastructure of our care economy by creating jobs and raising wages and benefits for essential home care workers.” The plan calls for Congress to invest $400 billion towards expanding access to quality, affordable home- or community-based care for aging relatives and people with disabilities. These investments will help Americans to obtain the long-term services and support they need, while creating new jobs and offering care workers a long-overdue raise, stronger benefits, and an opportunity to organize or join a union and collectively bargain. Research has shown that increasing the pay of care workers leads to better quality care overall. Through creating well-paying care jobs with benefits and o collectively bargaining rights, as well as building state infrastructure, the plan aims to improve both the quality of job for care workers and the quality of service for care recipients.

Lack of access to childcare makes it harder for parents, especially mothers, to fully participate in the workforce, hurting families and hindering U.S. growth and competitiveness. In areas with the greatest shortage of child care slots, women’s labor force participation is about three percentage points less than in areas with a high capacity of child care slots. The pandemic has severely exacerbated this problem with more than 1 in 4 facilities still remaining closed as of December 2020. President Biden is calling on Congress to provide $25 billion to help upgrade child care facilities and increase the supply of child care in areas that need it most. These funds are to be provided through a Child Care Growth and Innovation Fund for states to build a supply of infant and toddler care in high-need areas. Also included in this $25 billion is a call for expanded tax credits to incentivize businesses to provide care facilities at their establishments. This will grant accessible, high quality care and learning environments for children of employees. This particular part of the plan is structured so that employers will receive 50 percent of the first $1 million of construction costs per facility.

Investment in care is investment in infrastructure

As Cecelia Rouse, Chair of the Economic Advisors for the Biden administration, recently indicated during a recent press conference, we need to “upgrade our definition of infrastructure” to include the care economy. Rouse defended the Biden administration’s plan to spend $400 billion of the infrastructure plan’s budget on the care economy, defining it as a legitimate infrastructure investment and a key component to addressing economic inequities in the U.S. The care economy is critical to U.S. economic activity, and its absence would greatly hinder economic productivity. The inclusion of care work and the care economy in the American Jobs Plan is a critical first step in mending a critically broken care infrastructure in the U.S.

Still, it is only the first step. The U.S. is the only industrialized nation that fails to provide national paid family leave and medical leave programs, and where hundreds of thousand sit on waiting lists for desperately needed home care. LeadingAge, which represents service providers in the sector, estimates that half of all Americans will need long-term services and support after turning 65, and that by 2040, a quarter of the U.S. population will be 65 or older. In addition to the President’s proposal for the care economy, we also need investments to finally put America on a path to universal childcare and early learning, national paid family and medical leave and paid sick days for all workers. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed both the importance of care work and the vulnerabilities of our care infrastructure. At the same time, it has also created an opportunity for us to rethink the value of care and care work, opening ways for us to rebuild a more resilient care infrastructure and a more inclusive economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Economic Recovery, Policy, U.S.

What is the Care Economy and Why Should We Care?

In our project, we aim to promote and advocate for gender and socioeconomic equalities. We do this by working to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes and by showing and properly valuing social and economic contributions of caregivers; and integrating care into macroeconomic policy making toolkits.

In this era of demographic shifts, economic change and chronic underinvestment in care provisioning, innovative policy solutions are desperately needed, now more than ever. Sustainable and inclusive development requires gender-sensitive policy tools that integrate new understandings of care work and its connections with labor market supply and economic and welfare outcomes.

The Care Work and the Economy Project, currently based at the Economics Department of American University and co-led by Maria S. Floro and Elizabeth King, includes more than 30 scholars around the globe, working closely together to provide policy makers, scholars, researchers and advocacy groups with gender-aware data, empirical evidence and analytical tools needed to promote creative macroeconomic and social policy solutions. In the next phase of the project, Care Economies in Context, we will be scaling up our project to include 8 different countries, in 4 global regions. I will be leading this next phase of the project, which will be based at the University of Toronto.

I define Care work is defined broadly as work and relationships that are necessary for the health, welfare, maintenance and protection of all people – young and old, able bodied, disabled, and frail. This definition may seem broad – but care– at its core is a very basic human need and a necessity. Whether we know it or now, we all participate in providing care work – paid or unpaid, and in receiving care every day.

By care economy, I am referring to the sector of economy that is responsible for the provision of care and services that contribute to the nurturing and reproduction of current and future populations. More specifically, it involves child care, elder care, education, healthcare, and personal social and domestic services that are provided in both paid and unpaid forms and within formal and informal sectors.

Care work is important because it is important work that sustains life. It is also important now in particular because it is one of the fastest expanding economic sectors and a major driver of employment growth and economic development around the world. For example, across the OCED, the service sector economy now accounts for over 70 percent of total employment and GDP. In lower- and middle-income countries, it is estimated to comprise nearly 60 percent of GDP. Within the service sector economy, care services is one of the fastest growing subsectors.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that the global employment in care jobs is expected to grow from 206 million to 358 million by 2030 simply based on sociodemographic changes. The figure will be even more dramatic to 475 million if governments invest resources to meet the UN sustainable development goal targets on education, health, long-term care and gender equality.

In Canada, the service sector already makes up for 75 percent of employment and 78 percent of GDP. Within this sector, healthcare, social assistance and education services are key drivers of economic and employment growth. In the U.S., healthcare is already the largest employer, larger than steel and auto industries put together. In short, our current and future economy is and will be increasing dominated by care services and care work.

However, at the same time, much of the care work continues to be performed for no pay, by families and friends, at home and in communities. This unpaid care work is not including in in our national GDP because GDP only takes into account work that is done for pay in the formal market. Therefore, if we only look at the GDP as a measure of the economy and economy growth, we miss a huge segment of the economy and economic activities. As the pandemic has shown, without both paid or unpaid care work, our economy will not be able to function effectively, nor would it be able to sustain itself.

What we are trying to do in our project is to make the care economy clearer and more visible by measuring and mapping out the size and shape of the economy, and to develop macroeconomic models that would help policymakers and civil society actors to develop better policies and better strategies to ensure more sustainable and equality inducing economic growth.

Listen to the full talk “The Care Work and the Economy Project” to learn about what the care economy is and why we should know more about it, particularly now.

The blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care research cluster

- Published in Canada, Child Care, Economic Modeling, Elder Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, OECD