Climate Change and COVID-19: Why Gender Matters

This article was originally published in the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs on July 9, 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the important intersections of climate change, food security, migration, and socio-economic inequalities. An understanding of the gendered dimensions of these interconnected global concerns is crucial for developing a post-COVID recovery plan that ensures a more equal world and bolsters its resilience.

In many ways, the year 2020 spotlighted the compounding issues societies must reckon with, including climate change, COVID-19, and sustained inequality. Today, we are witnessing the drastic consequences of climate destabilization resulting largely from human actions: frequent heat waves, intense flooding and droughts, water crises, increased biodiversity loss, reduced agricultural productivity, and faster disease transmissions. Many of these underlying causes of climate change also increase the risk of future pandemics. For example, deforestation leading to loss of animal habitat forces animals to migrate and brings them into closer contact with other animals or people, increasing the likelihood of zoonotic transmission.

The effects of climate change are being felt throughout the world; its worst impacts are particularly damaging in poorer regions, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia. Severe and prolonged droughts have already affected the Sahel and most of East Africa. Meanwhile, severe storms and flooding are causing extensive damage across the world, and climate change-related food insecurity has resulted in thousands of deaths. Climate change has also intensified water scarcity, reaching critical levels in seventeen countries. Major rivers no longer reach the ocean, while reservoirs and lakes dry up and underground water aquifers are depleted. As climate change continues, drier areas will only be more prone to drought and humid areas more prone to flooding. As food, water, and other resources become increasingly strained, fierce competition over scarce natural resources is likely to escalate. In fact, natural disasters and climate-related conflicts have already dislocated millions of people. In 2017 alone, the UNHCR estimates about 30.6 million new displacements associated with conflicts across 143 countries and territories.

Making Gender Visible in Climate Change Issues

It is fundamental to note that these aforementioned issues are gendered. Gender disparities in access to resources such as land, credit, and extension training have put many women at greater risk with regards to maintaining their livelihoods and accessing food and water. Climate change not only reflects pre-existing gender inequalities, but it also reinforces them. The pivotal role of women in food security is well-documented. Recent estimates for Africa indicate that women provide 40 percent of labor in crop agriculture while at the same time providing labor in small livestock, poultry, and other food production-related activities. Many are income earners, serving as breadwinners in female-headed households while performing most of the household and family care work. However, gender inequalities in the ownership and control of household assets, gender discrimination in labor markets, and rising work burdens due to male out-migration undermine women’s income generating capabilities. Much of women’s work in food production and food access remain statistically invisible because conventional economic indicators fail to capture the significance of their contributions—contributions that are also overlooked in policymaking.

The gendered consequences of climate change include effects on migration flows. Migration has diversifies livelihoods and serves as an important coping mechanism through the promise of remittances or a better life. Internal and international migrations involve individuals and families seeking protection as refugees from the violence in their communities and states and those whose livelihoods are threatened by natural or man-made factors such as natural disasters, economic crises, or political instability. More recently, the increased frequency of extreme weather events and high temperatures have led to climate-induced migration flows exemplified by the influx of climate refugees seeking entrance into the United States in response to hurricanes, and rural-urban migration in Vietnam in response to typhoons.

The ability of households and their members to relocate varies depending on their resources and their vulnerability to the risk of falling further into poverty. Both the gendered dimension of migration and the climate shock impact on migration decisions are nuanced. Migration can challenge certain social expectations and cultural norms. Household care responsibilities and gender roles may restrain women from migrating. In the case of increased conflicts over natural resources, for instance, women are less able to flee than men as they are often responsible for taking care of the children. In Indonesia, climate shocks have promoted more migration among men. Similarly, male migration in Ethiopia and Nigeria has increased with drought and weather variability, while women are forced to stay put due to financial constraints. On the other hand, increasing demands for care workers in countries with high female labor force participation and aging populations provides employment opportunities for women, fueling international migration flows. In 2019 alone 48 percent of the 272 million (3.5 percent of the world’s population) international immigrants were female.

Gender and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The trends in climate-induced problems have foreshadowed the severity of the crises induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has affected all aspects of everyday life and work and has placed a heavy toll on families, communities, and economies. It threatens food security for tens of millions of people. The COVID-19 crisis, like the climate crisis, is causing disparate impacts across nations and social groups. It poses a much greater risk to elderly persons and those with underlying risk factors. Countries with fewer economic resources and weak social and health infrastructure are at a higher risk, not only in the short term but also in the longer term. Politically underrepresented groups suffer the most from lockdowns, rising unemployment, and unexpected medical costs, exacerbating existing economic inequalities.

More importantly, the COVID-19 crisis also unravels and further amplifies gender inequalities. As millions of people lose their jobs or become forced to work from home, many, especially mothers, are compelled to simultaneously juggle work and childcare responsibilities. Unpaid care work has increased not only with children out of school but also with the heightened care needs of the elderly and the sick, especially when health services are either inaccessible or overwhelmed. Ultimately, many women are earning less, saving less, working precarious or insecure jobs, or living close to poverty.

Gender-based violence is rapidly increasing as well. Many women are being forced to “lock down” at home with their abusers at a time when support services for survivors are being disrupted or made inaccessible. In Peru, the imposition of lockdowns has led to a 48 percent increase in phone calls to the helpline for domestic violence.

The COVID-19 pandemic also exposes the precarious employment conditions of many “essential workers” whose jobs increase their risks of infection and are often employed on temporary contracts. Migrants are among the key workers who deliver essential services; they play a critical role in essential sectors in many high-income countries working as crop pickers, food processors, care assistants, and cleaners in hospitals. These migrant workers help facilitate systemic resilience to threats, but their own vulnerabilities go unaddressed.

Conclusions

We cannot afford to ignore the particular vulnerability of women when analyzing the effects of climate change on food security and migration, and we cannot ignore their susceptibility to food insecurity and violence. As governments and policymakers grapple with the challenge of bolstering resilience, they will need to think beyond the effects of these shocks on markets and to pay more attention to the heightened social and economic inequalities. Such an objective requires a comprehensive, gendered approach that considers women’s roles in the provision of essential goods and services and the differentiated impacts of climate change.

Fiscal stimulus packages and emergency measures have been put in place by many countries to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19, but it is crucial that these responses as well as post-COVID recovery plans put women and girls’ interests and needs, rights, and protection at their center. Such responses and plans should include expanded public investment in the care delivery system, from childcare to healthcare to eldercare, which the COVID-19 crisis has disrupted. There is also a need for gender-sensitive analyses of the effects of economic, social, and migration policies along with the development of legal frameworks that effectively address domestic violence. Meaningful participation of women in policy discourse and dialogue addressing climate change is vital as they are disproportionately vulnerable.

Governments should also undertake and support the collection of sex-disaggregated data on various economic, social, and climate-change related indicators as the lack of data is sometimes used as an excuse not to implement gender-responsive policies. As UN Women has stated, “it is not just about rectifying long-standing inequalities but also about building a more just and resilient world.”

This article was written by the CWE-GAM Project’s Principal Investigator Maria S. Floro and was originally published in the Georgetown Journal for International Affairs on July 9, 2021.

- Published in COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy, Maria Floro, Policy

“Girly Issues” Are Now the Country’s Issues

Dr. Nancy Folbre, an Advisor and Researcher of the CWE-GAM project and a groundbreaking feminist economist was among the first to sound the alarm about the care crisis. Dr. Folbre’s work on the care sector, once considered “just girly issues” by fellow economists, are now recognized as issues belonging to the U.S.. Previously the recipient of the 1998 MacArthur “genius” grant, Dr. Folbre’s research has journeyed from “fringe idea to more mainstream policy.”

Once cast aside in policy discussions, the care crisis is finally getting the spotlight it deserves after the pandemic forced many schools and child-care centers to close, leaving “ten million mothers of school-age children out of the workforce.” The pandemic is forcing policymakers to finally face the cracks in America’s care infrastructure that Dr. Folbre and other experts have long pointed out— “a system where working parents do not have reliable, affordable child care is one where they cannot reliably build a career.”

To learn more about Dr. Folbre’s work on care, visit her blog Care Talk and read her recent book The Rise and Decline of Patriarchal Systems.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics

CWE-GAM Scholars Leading Two Panels During 2021 IAFFE Annual Conference

This week, the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) will hold its Annual Conference: “Sustaining Life: Challenges of Multidimensional Crises” starting on Tuesday, June 22nd, and concluding Friday, June 25th. This conference will provide a forum for scholars to discuss feminist approaches to constructing “inclusive and resilient economic and political systems and [sustainting] our environment” in the context and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Care Work and the Economy Project will be leading two panel discussions on Wednesday, June 23rd and Thursday, June 24th: “Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” chaired by Elizabeth King and Ito Peng, and “Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” chaired by Young Ock Kim. In the discussions, CWE-GAM researchers will present gender-aware macroeconomic models, data collected from unique surveys of care providers and families, and microeconomic simulations used to better understand care work and the economy.

“Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” is scheduled for Wednesday, June 23rd from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time) and will contribute to ongoing efforts to “illustrate the intersectionality of care provisioning, economic growth, and distribution.” With an increasing need for care due to the rapid decline in fertility rates and aging population, South Korea offers a unique context to introduce models and analyze surveys given to households, child and eldercare workers.

There will be four papers presented in this panel:

“The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The Case of South Korea” by Cem Oyvat and Ozlem Onaran “introduces a post-Kaleckian feminist model to analyze the effects of public social expenditure and gender gaps on output and employment building on Onaran, Oyvat, and Fotopoulou (2019), and extending it with an endogenous labor supply and wage bargaining model.”

“The Quality of Life of Family Caregivers: Psychic, Physical, and Economic Costs of Eldercare in South Korea” by Jiweon Jun, Elizabeth King, and Catherine Hensly “examines the psychic, physical, and opportunity costs of caregiving within the family using data from a special-purpose national survey of 501 households conducted in Seoul in 2018.”

“Quality of Care, Commitment Level, and Working Conditions: Understanding the Care Workers’ Perspective” by Shirin Arslan, Maria Floro, Arnob Alam, Eunhye Kang, and Seung-Eun Cha uses “the 2018 Care Work Economy (CWE-GAM) survey data collected from 600 child and eldercare workers in South Korea [to] analyze patterns of commitment levels among [paid carers] in various settings such as private and public institutions as well as in homes of recipients by conducting tobit regressions and entropy econometrics for robustness checks.”

“Impacts of COVID-19 on Work-Family Balance in South Korea: Empirical Findings and Policy Implications” by Ito Peng and Jiweon Jun examines COVID-19’s unequal impact between men and women in South Korea using data from a survey distributed to “1,252 households with at least one child aged between 0 and 12 in June 2020 to find out how the first 2-month social distancing measure had affected their work, childcare arrangements, and their wellbeing.”

“Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” is scheduled for Thursday, June 24th from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time), which will share the results of gender-aware applied modelings and micro simulations for South Korea. The panel will discuss which fiscal policies are likely to be the most effective at reducing gender gaps in paid employment and which forms of public investment best contribute to reducing and redistributing unpaid work between genders and socio-economic groups.

There will be three papers presented in this panel:

“Child and Elderly Care in South Korea: Policy Analysis with a Gendered, Care-Focused Computable General Equilibrium Model” by Martin Cicowiez and Hans Lofgren presents the first care-focused and gendered model in the computable general equilibrium literature for Korea that “is built around a social accounting matrix (SAM) that covers non-GDP household services, singles out sectors for child and elderly care, and disaggregates households on the basis on care needs.”

“Care Support Ratios in Korea and the US” by Gretchen S. Donehower and Bongoh Kye takes a holistic view of care by including both paid and unpaid care for all age ranges and “create[s] [care support ratios] to understand the current care market and whether it is sustainable in the future…in two aging populations- Korea and the United States.”

“Towards a Caring and Gender-Equal Economy in South Korea: How much does the regulation of labor market working hours matter?” by Ipek Ilkkaracan and Emel Memis “use[s] a unique time-use survey on care arrangements by couples with small children in order to explore the potential of [the] reduction of full-time market work hours towards [the] narrowing of the gender gaps in paid and unpaid work.”

To learn more about the panels presented by CWE-GAM researchers and the IAFFE conference, please visit the IAFFE 2021 Annual Conference homepage and program.

This blog was contributed by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

What is the Care Economy and Why Should We Care?

In our project, we aim to promote and advocate for gender and socioeconomic equalities. We do this by working to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes and by showing and properly valuing social and economic contributions of caregivers; and integrating care into macroeconomic policy making toolkits.

In this era of demographic shifts, economic change and chronic underinvestment in care provisioning, innovative policy solutions are desperately needed, now more than ever. Sustainable and inclusive development requires gender-sensitive policy tools that integrate new understandings of care work and its connections with labor market supply and economic and welfare outcomes.

The Care Work and the Economy Project, currently based at the Economics Department of American University and co-led by Maria S. Floro and Elizabeth King, includes more than 30 scholars around the globe, working closely together to provide policy makers, scholars, researchers and advocacy groups with gender-aware data, empirical evidence and analytical tools needed to promote creative macroeconomic and social policy solutions. In the next phase of the project, Care Economies in Context, we will be scaling up our project to include 8 different countries, in 4 global regions. I will be leading this next phase of the project, which will be based at the University of Toronto.

I define Care work is defined broadly as work and relationships that are necessary for the health, welfare, maintenance and protection of all people – young and old, able bodied, disabled, and frail. This definition may seem broad – but care– at its core is a very basic human need and a necessity. Whether we know it or now, we all participate in providing care work – paid or unpaid, and in receiving care every day.

By care economy, I am referring to the sector of economy that is responsible for the provision of care and services that contribute to the nurturing and reproduction of current and future populations. More specifically, it involves child care, elder care, education, healthcare, and personal social and domestic services that are provided in both paid and unpaid forms and within formal and informal sectors.

Care work is important because it is important work that sustains life. It is also important now in particular because it is one of the fastest expanding economic sectors and a major driver of employment growth and economic development around the world. For example, across the OCED, the service sector economy now accounts for over 70 percent of total employment and GDP. In lower- and middle-income countries, it is estimated to comprise nearly 60 percent of GDP. Within the service sector economy, care services is one of the fastest growing subsectors.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that the global employment in care jobs is expected to grow from 206 million to 358 million by 2030 simply based on sociodemographic changes. The figure will be even more dramatic to 475 million if governments invest resources to meet the UN sustainable development goal targets on education, health, long-term care and gender equality.

In Canada, the service sector already makes up for 75 percent of employment and 78 percent of GDP. Within this sector, healthcare, social assistance and education services are key drivers of economic and employment growth. In the U.S., healthcare is already the largest employer, larger than steel and auto industries put together. In short, our current and future economy is and will be increasing dominated by care services and care work.

However, at the same time, much of the care work continues to be performed for no pay, by families and friends, at home and in communities. This unpaid care work is not including in in our national GDP because GDP only takes into account work that is done for pay in the formal market. Therefore, if we only look at the GDP as a measure of the economy and economy growth, we miss a huge segment of the economy and economic activities. As the pandemic has shown, without both paid or unpaid care work, our economy will not be able to function effectively, nor would it be able to sustain itself.

What we are trying to do in our project is to make the care economy clearer and more visible by measuring and mapping out the size and shape of the economy, and to develop macroeconomic models that would help policymakers and civil society actors to develop better policies and better strategies to ensure more sustainable and equality inducing economic growth.

Listen to the full talk “The Care Work and the Economy Project” to learn about what the care economy is and why we should know more about it, particularly now.

The blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care research cluster

- Published in Canada, Child Care, Economic Modeling, Elder Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, OECD

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part II

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” The discussion describes the interconnections between the crisis of care, the deepening ecological crisis and growth and accumulation processes.

There are many common threads with the climate and ecological crisis and the care crisis. Significantly, the idea that economic growth is overall beneficial. The type of economic growth generally pursued worldwide has not only increased stresses put upon the earth’s resource base but also on care labor capacity, which is similarly but wrongly perceived to be of infinite supply. Moreover, arguments that equate economic growth with overall improvement fail to recognize the distributional element of rising income inequality, which is far more nuanced. In fact, among countries that are higher income, gains from economic growth within those nations do not trickle down to everyone. When looking at care, the widening income equality gaps has shifted distribution of care givers across social classes and national boundaries. As a result, the quality and adequacy of care within a single nation can be very different, which exacerbates differences in social reproduction.

At the same time, income inequality has created a solution for the care needs of those that have the means to hire care for children and elderly, because care workers in those sectors are often paid low wages. But for the working poor, hiring care work help is inaccessible due to financial constraints, therefore they rely on their kinship networks to help provide this care. Furthermore, much of the care work burden still falls on women even as they enter to labor force. Economics and social policy in many parts of the world continue to neglect the heavy work burden put upon women and the necessity to balance household care activities and market work. What can also be observed is a global care supply chain, with the migration of women and girls to urban areas to provide care for wealthier families. Care itself is becoming one of the drivers of income inequality.

The economy is not all about material production; it is really about human vision and social provisions. However, an illusion has been created that unpaid care work is a natural resource that serves as an input for market production to promote GDP growth. However, this idea does not take into account that the wellbeing of people, especially the elderly, the sick and children should be an end in and of itself, to achieve sustainable growth. There is much work to be done to address these issues. To begin, economists must envision long term horizons that look forward to future generations while also taking into account the interdependence of life and moral responsibility. They must also integrate care and environmental consequences into our economic policy tools. Overall a new economic paradigm that includes green ecology and feminist economic concerns is needed.

Link to Part 1 of this blog here.

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part I

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” This discussion delves into the foundation of project itself, its context, the analytical tools utilized in the research, as well as the external factors that have served as the catalyst for the work being done.

The Care Work and the Economy Project was developed after a group of feminist economists observed that in the effort to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes, as laid out within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, there were aspects of care work that needed to be addressed. The project includes 35 scholars from all around the world that are working to develop innovative analytical tools. The research has been applying and testing these tools in South Korea, a country that quickly industrialized in the 70s and 80s and therefore witnessed a very rapid demographic change in fertility and life expectancy.

The care economy, which is inclusive of caring for those that cannot care for themselves, underpins the production of all economies within society. This begins with the fact that if people stopped having children, which require care, then the economy would come to a halt due to lack of labor force. Generally, care work has a tendency to be undermined through a lack of gender awareness in macroeconomic modeling, which does not address care needs in any adequate manner. This aspect is also neglected within the policy making discourse, with the current economic paradigm failing to take into account the necessity for care work to achieve economic growth.

Economic models that display growth also fail to take into consideration social elements, making the assumptions that, for example, children will be cared for despite the lack of social investment into care. However, with care work there comes social, political and economic significance. The Care Work and the Economy project is working to demonstrate what a care focused macroeconomic model can reveal through the implementation of the analytic tools being developed and implemented through the research.

The absence of the care economy within macroeconomic models is in large part due to it being “invisible” since the work often unpaid. This has led to the neglect of care needs despite unpaid care work providing indispensable services in terms of economic activity and growth. The result is an emerging care crisis that has manifested itself in terms of uncared for elderly, sick and children. Furthermore, the crisis has provoked a form of silent protest against long unpaid work hours performed by women, leading to a decline in marriage and fertility rates. This in turn has resulted in a reproduction crisis.

The Care Work and the Economy project researchers are developing and using innovative analytical tools to bring care to the forefront, along with a deeper understanding of the nature of care work, while illustrating the intersectionality between care provisioning, economic growth and distribution. Although these analytical modeling tools are currently being applied in South Korea, the project believes they can be adopted and implemented into other countries as long as the provision of care is taken into context of those countries. The project research shows that governments have an important role and duty to invest in care provisions as well as comprehensive national care plans. One of the key findings is that it is important to take into account demographic change and climate change along with economic and structural changes taking place in policy making. This is a tall order but necessary to sustain economies and provide a future for next generation.

Link to Part 2 of this blog here.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

Spirals of Inequality: A Women’s Budget Group Special Report

The Women’s Budget Group Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy, launched in February 2019, is an expert-led project aimed at developing economic policies that promote gender equality across the United Kingdom. The Commission utilizes a number of avenues and tools to achieve this objective, one of which is the recent release of the report “Spirals of Inequality: How Unpaid Care is at the Heart of Gender Inequalities.”

This first report released by the Commission seeks to trace the problem of how gender inequalities in the UK are produced and maintained by observing the problem through the following perspectives:

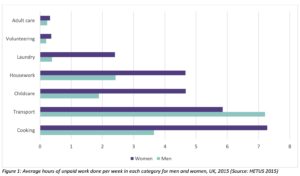

Unpaid Work: Women Continue to do the Lion’s Share

The unequal division of labor within unpaid care work is at the heart of gender inequality in the UK, with women taking on 60% of the unpaid work on average. This includes care work, cooking, and cleaning among other tasks.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

Limiting Opportunities for Paid Work: Women More Likely to Work Part-Time and Earn Less

This phenomenon puts a disproportionate strain on women and contributes to gender inequality. Mothers with young children are 3-4 times more likely to work part-time, and women, in general, are far more likely to be in precarious forms of employment such as temporary work. This is especially true for women of color. The part-time work conundrum is driving the gender gap, and on average women earn 43% less than men. Furthermore, a pay gap of 8.9% persists, further exacerbating this issue. Again, this being more predominate with women of color.

Despite women becoming increasingly educated, they persist in being overrepresented in low-wage sectors of the economy such as health and social work. Feminist economists have argued that a reason behind this is such sectors are viewed as an extension of a women’s “natural” work.

These issues create a perpetual cycle that allows for the inequality between men and women to continue.

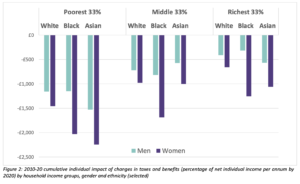

Life Course Implications: Benefits Make Up a Larger Portion of Income and Austerity Hits Harder

Among single households living in poverty, those led by women make up for 86%. Furthermore, pensioners living alone are far more likely to be at the poverty level if that individual is a woman. Since tax reforms began in 2010 throughout the UK, women have also been hit hardest. These benefits make up a large portion of women’s incomes and cuts to these benefits and tax giveaways benefit those fitting into a higher wealth bracket.

Public Services: Women Hit Hardest by Cutbacks

Cuts to public spending throughout the UK have also hit women disproportionately hard, as women are most likely to utilize public services. The poorest families and especially those in poverty-level households led by women have taken a particularly bad hit; many single mothers have had to cut living standards by up to 10% as a result of a cut to public services between 2010 and 2017.

Furthermore, these cuts have put a greater burden on family members to provide care for the elderly members of their family, much of this falling onto female members. This often comes at the expense of their own employment.

Violence Against Women: “Cause and Consequence” of Women’s Economic Equality

All of the factors that lead to the economic disparity between men and women also make it increasingly difficult for women to leave abusive partners. Furthermore, poorer households have higher rates of domestic abuse, and this perpetuating poverty limits women’s options while increasing their vulnerability.

Moving Forward: Next Steps for the Commission

The WBG Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy is striving to develop an alternative economic approach aimed at addressing these issues. Through this initiative, they aim to build an economy that is desirable, economically feasible, and necessary for fairness, sustainability, and resilience. To learn more about the Commission and its work, sign up to attend the upcoming webinar “Creating a Caring Economy: A Call to Action” on September 30, 2020.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy

The Covid-19 Care Penalty

In the U.S., as elsewhere, essential workers have been rightly praised for their willingness to take on additional risk and stress. Their commitment to helping patients, students, and customers face-to-face went beyond the ordinary requirements of earning a paycheck. Yet some essential workers faced more serious risks of infection than others, and differences in pay among them were also significant. The abrupt creation of a new category of workers based on social need, rather than market forces, dramatized an important question: why do we often see a disjuncture between the social value of work and its private, pecuniary reward?

Feminist research addresses this question in a number of ways, emphasizing factors such as employer discrimination, monopoly or monopsony power, and intersectional differences in the relative bargaining power of distinct groups of workers. The distinctive features of care work—intrinsic motivation, emotional skills, team production, and positive spillover effects—have also received attention. Leila Gautham, Kristin Smith and I have been building on previous research on care penalties to show that essential workers in care services (health, education, and social service industries) are paid less than other essential workers (in law enforcement, support and waste services, transportation, agriculture, retail and financial industries) with comparable personal and work characteristics, a pattern with especially costly consequences for women. Low-wage workers such as health aides are especially vulnerable, but care penalties also help explain the vulnerability of doctors and nurses in ways mediated by unique institutional features of the U.S. health care system.

A paper on this research is now under review. Once this process is complete, I’ll come back with more details.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on June 11, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in COVID 19, Feminist Economics

Unpaid Work, Animated

About half of all the time devoted to work in the U.S. is devoted to unpaid work in the home. The Institute for New Economic Thinking has created an adorable animation of some comments I made in an interview with them on this topic a while back.

It’s quite a lot of fun, and basically accurate. Just don’t pay too much attention to the numbers they inserted into my discussion of two families, each with a market income of $50,000–the animation seems to imply that leisure should be assigned a monetary valuation–not something I advocate. Still, the main point comes through just fine: conventional measures provide a misleading picture of living standards.

The animation provides a great introduction to the topic for students, and you can find a more academic version of the basic argument in a short briefing paper I wrote for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on June 11, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, Rethinking Macroeconomics