What is the Care Economy and Why Should We Care?

In our project, we aim to promote and advocate for gender and socioeconomic equalities. We do this by working to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes and by showing and properly valuing social and economic contributions of caregivers; and integrating care into macroeconomic policy making toolkits.

In this era of demographic shifts, economic change and chronic underinvestment in care provisioning, innovative policy solutions are desperately needed, now more than ever. Sustainable and inclusive development requires gender-sensitive policy tools that integrate new understandings of care work and its connections with labor market supply and economic and welfare outcomes.

The Care Work and the Economy Project, currently based at the Economics Department of American University and co-led by Maria S. Floro and Elizabeth King, includes more than 30 scholars around the globe, working closely together to provide policy makers, scholars, researchers and advocacy groups with gender-aware data, empirical evidence and analytical tools needed to promote creative macroeconomic and social policy solutions. In the next phase of the project, Care Economies in Context, we will be scaling up our project to include 8 different countries, in 4 global regions. I will be leading this next phase of the project, which will be based at the University of Toronto.

I define Care work is defined broadly as work and relationships that are necessary for the health, welfare, maintenance and protection of all people – young and old, able bodied, disabled, and frail. This definition may seem broad – but care– at its core is a very basic human need and a necessity. Whether we know it or now, we all participate in providing care work – paid or unpaid, and in receiving care every day.

By care economy, I am referring to the sector of economy that is responsible for the provision of care and services that contribute to the nurturing and reproduction of current and future populations. More specifically, it involves child care, elder care, education, healthcare, and personal social and domestic services that are provided in both paid and unpaid forms and within formal and informal sectors.

Care work is important because it is important work that sustains life. It is also important now in particular because it is one of the fastest expanding economic sectors and a major driver of employment growth and economic development around the world. For example, across the OCED, the service sector economy now accounts for over 70 percent of total employment and GDP. In lower- and middle-income countries, it is estimated to comprise nearly 60 percent of GDP. Within the service sector economy, care services is one of the fastest growing subsectors.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that the global employment in care jobs is expected to grow from 206 million to 358 million by 2030 simply based on sociodemographic changes. The figure will be even more dramatic to 475 million if governments invest resources to meet the UN sustainable development goal targets on education, health, long-term care and gender equality.

In Canada, the service sector already makes up for 75 percent of employment and 78 percent of GDP. Within this sector, healthcare, social assistance and education services are key drivers of economic and employment growth. In the U.S., healthcare is already the largest employer, larger than steel and auto industries put together. In short, our current and future economy is and will be increasing dominated by care services and care work.

However, at the same time, much of the care work continues to be performed for no pay, by families and friends, at home and in communities. This unpaid care work is not including in in our national GDP because GDP only takes into account work that is done for pay in the formal market. Therefore, if we only look at the GDP as a measure of the economy and economy growth, we miss a huge segment of the economy and economic activities. As the pandemic has shown, without both paid or unpaid care work, our economy will not be able to function effectively, nor would it be able to sustain itself.

What we are trying to do in our project is to make the care economy clearer and more visible by measuring and mapping out the size and shape of the economy, and to develop macroeconomic models that would help policymakers and civil society actors to develop better policies and better strategies to ensure more sustainable and equality inducing economic growth.

Listen to the full talk “The Care Work and the Economy Project” to learn about what the care economy is and why we should know more about it, particularly now.

The blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care research cluster

- Published in Canada, Child Care, Economic Modeling, Elder Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, OECD

The Unpaid Care Work and the Labor Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys

How much time do people spend on doing paid and unpaid care work? How do women and men spend their time differently on unpaid care work? Are there any differences in time use among the regions? How do socioeconomic factors influence people’s choices to do paid and unpaid care work?

Jacques Charmes addresses these questions in recent ILO report by providing a comprehensive overview of the extent, characteristics and historical trends of unpaid care work. The report is based on the analysis of the most recent time-use surveys carried out at the national level across the world, revealing the differences in time spent on unpaid care work between women and men and among people with different socioeconomic characteristics, such as geographical location, age and income groups, education level, marital status and the presence and age of children in the household. An insightful discussion of the concepts and methodological approaches underlying the analysis of time-use data is also offered.

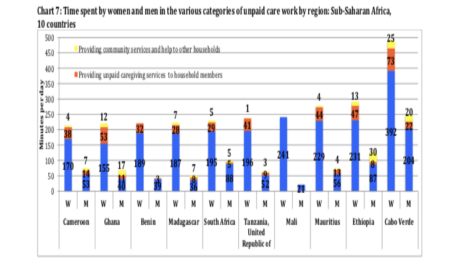

Chart 7 in the ILO Working Paper the Unpaid Care Work and the Labour Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys illustrates the time spent by women and men in various categories of unpaid care work across Sub-Saharan African countries including Cameron, Ghana, Benin, Madagascar, South Africa, Tanzania, Mali, Mauritius, Ethiopia and Cabo Verde. As with the case around the world, women in Sub-Saharan African countries are providing significantly more unpaid care services in households and communities. Read the report to learn more about time-use analysis concepts and methodologies, gender variations in paid and unpaid work across the world and across various socio-economic levels:

International Labour Organization

Gender, Equality and Diversity & ILOAIDS Branch

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy Briefs & Reports

Invisible Frontliners: Migrant Care Workers in the Time of COVID-19

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed fault lines in national healthcare and social protection systems that have made many countries – developed as well as developing – unable to quickly and efficiently deal with this new health crisis and its disastrous consequences on jobs and incomes. One segment of the population in Europe, North America and Asia’s wealthy countries is falling deep into these crevasses, and, sadly, is missing from national debates and policy agendas on the Covid-19 crisis. This group comprises the migrant care workers, especially those who provide care services to elderly, frail, and dependent persons in caregiving institutions and private homes.

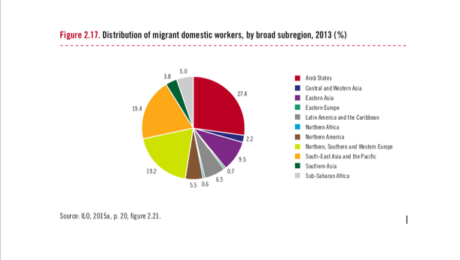

Overwhelmingly consisting of women, these migrant workers (along with minority ethnic groups) are the backbone of the childcare, elderly care and long-term care sectors. They include “nannies”, “home carers”, “social care workers”, “collaboratrice familiar”, nurses and nursing aides, among others. According to the European Commission, workers engaged in “personal and household services” are mostly women, working mainly part-time and often of migrant background. ILO estimates that globally there are 11.5 million international migrant domestic workers, and nearly 80 percent of them are employed in OECD countries. According to data on OECD countries, in 2012–13 28 percent of home-based caregivers were foreign-born.

Increasingly restrictive immigration controls in high-income countries in the past two decades have channelled a disproportionate share of immigrants into jobs in informal long-term and home-based care where wages are low, work hours are long and unpredictable, protection from abuse may be missing, and workload is heavy.[1] These are jobs that can easily be concealed from government surveillance. In the US, UK and Canada, for example, most foreign-born care workers enter the country through non-employment routes, such as family unification, refugee protection and asylum programs, and are on student, tourist and working holiday visas. An unknown number of them work clandestinely.

These migrant care workers are particularly vulnerable in the current Covid-19 pandemic for several reasons. First, eldercare homes across Europe and North America have emerged as hotspots of COVID-19 cases and account for a disproportionate share of deaths related to COVID-19. Data collated by the International Long-term Care Policy Network (hosted by the London School of Economics) across five European countries suggest that between 42 and 57 percent of deaths related to COVID-19 have so far occurred in nursing homes.

Secondly, the disproportionate and increasing share of COVID-19 deaths in eldercare homes is not simply due to the residents’ higher vulnerability due to their age and health conditions. It is also because many caregivers in these homes lack access to PPEs and are often overworked in often understaffed facilities. Being poorly paid, some of them also work in multiple facilities just to make ends meet. Poor working conditions of migrant workers in long-term and eldercare homes have been well documented by several studies – conditions regarding their work hours, allocation of responsibilities for diverse tasks and more difficult patients, low pay rates, and no overtime compensation.

Thirdly, the hundreds of thousands of migrant domestic workers who work in private homes are in the frontlines of keeping homes safe and clean. They face multiple risks as a result of the pandemic – health risks, more demands on their time, and income loss. According to the International Domestic Workers Federation, domestic workers worldwide have reported many concerns since the global pandemic began. With entire families staying home all day due to quarantine measures, domestic workers face heavier demands of cooking, cleaning, and caregiving without the benefit of additional pay for longer hours—and because of mobility restrictions, many cannot leave the homes where they work.

Finally, many care workers who have irregular migrant and/or employment status under informal arrangements have no access to unemployment and health insurance benefits, relief packages or financial aid related to COVID-19. This has been recently documented by the National Domestic Workers Alliance and the Pennsylvania Domestic Workers Alliance (networks representing nannies, caregivers and domestic workers in the US), the European Trade Union, and the Kanlungan Filipino Consortium in the UK. Those who fall ill prefer not to go to hospitals until it is too late for fear of being reported to migration authorities and because they do not have health insurance. These care frontliners are largely invisible and likely to suffer in silence

Contributed by Amy King-Dejardin, Former senior staff of ILO (Geneva) and author of the 2018 ILO report, “The Social Construction of Migrant Care Work.”

[1] King-Dejardin, A., 2019, The social construction of migrant care work, Geneva: ILO https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-migration/publications/WCMS_674622/lang–en/index.htm

*Learn more about the ILO Bureau of Gender Equality here

- Published in COVID 19, Migrant Care Workers

Domestic and Care Workers Under COVID-19

By definition, domestic workers are an essential part of the global care workforce. According to the ILO, there are 70 million domestic workers over the age of 15 working directly for private households. They therefore make up roughly 22.7% of the global care workforce (which number 308,6 million).[1] Since its foundation in 2013, the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) has worked with global unions and key audiences with the aim of including home care workers into the global agenda on “care” and to fight for the improvement of their living and working conditions.

Work in the care sector changes rapidly due to aging populations in the west and the more industrialized part of Asia. Financial demands on families who rely on unpaid care work, or the reliance by governments on private and not-for-profit sectors to play an increasing role in providing services. In Asia, most governments deny labour rights and working conditions, particularly for migrant workers, In the west, there is an increasing number of undocumented migrant domestic workers and they do not enjoy labour rights protection due to their vulnerable status. In recognition of the challenges in care work, in 2018 the IDWF Congress adopted two Resolutions (No. 3 & 4) to guide the Federation’s work and address global demands on developing inclusive care systems, special protection programs, and special attention to undocumented and migrant worker’s needs.

The new coronavirus pandemic has impacted all regions for more than three months. Domestic, household and care workers are on the frontlines in keeping families and communities healthy, but they are also most at risk. COVID19 has increased the vulnerability of the sector, which is already and broadly characterized by lack of protections, social security or recognition in many places of the world.

The IDWF consists of 74 affiliates in 57 countries, representing almost 600,000 domestic workers. Since the pandemic began, the IDWF has been actively engaging with affiliates in all regions to monitor the situation on the ground. In many countries, workers are experiencing a substantial increase in workload to ensure cleanliness and hygiene; or in taking care of older people and people with existing medical conditions.

The most critical issues identified:

– Domestic and care workers, especially the live-out/ part time are the most vulnerable group. They cannot move around and lose their jobs due to the lockdowns and social distancing rules, or their employers no longer call them in to work. Many have endured this situation for several weeks while others are losing their jobs with no prospects of finding new sources of income.

-Without income, migrant workers are especially vulnerable as they try to survive in the destination countries. In many countries, migrant workers are not eligible for medical services and hence do not get COVID-19 tests, places for quarantine or medical treatment when needed.

-Workers from rural areas working in the cities, cannot return to their families, or access relief packages provided by local governments.

-The lack of medical and social protections benefits renders domestic and care workers unprotected even when they are sick or need to be quarantined with no remuneration. IDWF and Affiliates are monitoring the mortality rates of members, a difficult task as many governments do not test or report incidents.

-Despite the essential work, domestic and care workers face increasing discrimination during the pandemic. Many workers report for being blamed for bringing the virus into their employers’ homes.

-The ability of domestic workers unions to keep their offices functioning is also compromised during quarantine or semi-quarantine time. Many unions are able to pay for the basic services and provide essential support (i.e. information, food baskets, training) from income previously generated. It is essential that union offices keep operating and maintaining their services for a range of situations that go from unfair dismissals to gender based violence.

In this situation, most organizations have shifted or stopped normal activities. With exception to those in North America and Europe, most organizations are struggling to find ways and means to address emergencies. Some countries have included domestic workers in their relief programs while others have joined hands with allies to demand governments to give out wages /cash, food, masks, sanitizers, places for quarantine. As the pandemic continues, so will the crisis on the ground.

Based on its assessment, the IDWF will continue to do research and collect data to inform advocacy. The IDWF will also set up a solidarity fund to address some of the most critical needs to enable domestic/care workers –and their families– to cope and survive with COVID-19.

[1] ILO (2018), Geneva. Care Work and Care Jobs For the Future of Decent Work.

Contributed by Sofia Trevino, Sustainability Advisor for International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) and the Project Manager for Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO)

Relevant Links:

IDWF: Decent work for Domestic Workers: Eight Good Practices from Asia

In IDWF site, resources on care work (books, articles, websites, audio)

An essay collection on Care economy: Three Years of Collective and Global Learning About Care

ILO Decent Work in the Care Economy

Care Needs and Migration for Domestic Work: Poland and Ukraine

Migrant Domestic Workers: Promoting Occupational Safety and Health

Expanding Social Security to Migrant Domestic Workers

IDWF Resolutions adopted by the 2nd Congress in 2018, Cape Town, South Africa

ILO: Social Protection for Domestic Workers: Key Policy Trends and Statistics

ILO World of Work Magazine: Violence at Work

Decent Work for Domestic Workers: Eight Good Practices from Asia, ILO and IDWF

Why We Care about Care: An Online Moderated Course on Care Economy, UN Women

Research Network of Domestic Workers Rights

WIEGO:

UN High Level Panel Report on Child Care by Rachel Moussié, Deputy Director of WIEGO Social Protection Programme.

Counting the World’s Informal Workers: A Global Snapshot

The ILO – WIEGO policy brief series on childcare for informal workers

Sofia Trevino is the Sustainability Advisor for International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) and the Project Manager for Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO)

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Domestic Workers, Policy Briefs & Reports