Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective

Below is an excerpt from a recent piece “Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective” by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group. This article was published by Migrants and Systemic Resilience: A Global COVID19 Research and Policy Hub (Mig-Res-Hub).

In this think-piece I consider how we can build a resilient systemic response to the COVID-19 pandemic and future crises. I focus on systemic resilience in relation to carework and global migration of careworkers, and I approach this from an Asia-Pacific perspective. One of the fault lines exposed by the COVID-19 is the vulnerability of the existing care, carework and migration infrastructure to exogenous shocks. Asia-Pacific is an important site to examine because it is one of the major sites of global care migration, both as sender and receiver of migrant careworkers. This think-piece draws on the research from our global partnership project based at the University of Toronto, which looks at the dynamics of careworker migration in Asia-Pacific and the interconnections between social and economic forces and policies in shaping those dynamics from both sending and receiving country perspectives. The next section briefly outlines the pandemic’s impacts on carework and care migration in Asia-Pacific. I then discuss how we might achieve systemic resilience in global care migration by first emphasizing how our care systems are interlocked with the global migration of careworkers (what I call a global care interlock), and second, how we might achieve systemic resilience. Understanding the global care interlock is an important prerequisite to systemic resilience because it allows us to see carework and migration of careworkers as a part of a larger global infrastructure or ecosystem that has been, consciously or unconsciously, built, managed and sustained by multiple actors in different parts of the globe.

Read the entire article here.

This blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing research for the Understanding and Measuring Care research group.

- Published in Asia-Pacific, Child Care, COVID 19, Elder Care, Migrant Care Workers, Understanding and Measuring Care

Invisible Frontliners: Migrant Care Workers in the Time of COVID-19

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed fault lines in national healthcare and social protection systems that have made many countries – developed as well as developing – unable to quickly and efficiently deal with this new health crisis and its disastrous consequences on jobs and incomes. One segment of the population in Europe, North America and Asia’s wealthy countries is falling deep into these crevasses, and, sadly, is missing from national debates and policy agendas on the Covid-19 crisis. This group comprises the migrant care workers, especially those who provide care services to elderly, frail, and dependent persons in caregiving institutions and private homes.

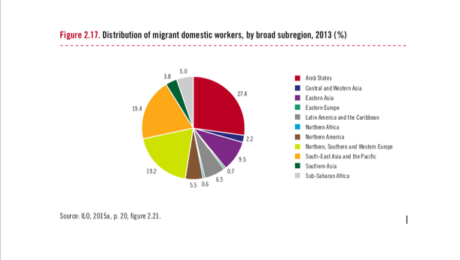

Overwhelmingly consisting of women, these migrant workers (along with minority ethnic groups) are the backbone of the childcare, elderly care and long-term care sectors. They include “nannies”, “home carers”, “social care workers”, “collaboratrice familiar”, nurses and nursing aides, among others. According to the European Commission, workers engaged in “personal and household services” are mostly women, working mainly part-time and often of migrant background. ILO estimates that globally there are 11.5 million international migrant domestic workers, and nearly 80 percent of them are employed in OECD countries. According to data on OECD countries, in 2012–13 28 percent of home-based caregivers were foreign-born.

Increasingly restrictive immigration controls in high-income countries in the past two decades have channelled a disproportionate share of immigrants into jobs in informal long-term and home-based care where wages are low, work hours are long and unpredictable, protection from abuse may be missing, and workload is heavy.[1] These are jobs that can easily be concealed from government surveillance. In the US, UK and Canada, for example, most foreign-born care workers enter the country through non-employment routes, such as family unification, refugee protection and asylum programs, and are on student, tourist and working holiday visas. An unknown number of them work clandestinely.

These migrant care workers are particularly vulnerable in the current Covid-19 pandemic for several reasons. First, eldercare homes across Europe and North America have emerged as hotspots of COVID-19 cases and account for a disproportionate share of deaths related to COVID-19. Data collated by the International Long-term Care Policy Network (hosted by the London School of Economics) across five European countries suggest that between 42 and 57 percent of deaths related to COVID-19 have so far occurred in nursing homes.

Secondly, the disproportionate and increasing share of COVID-19 deaths in eldercare homes is not simply due to the residents’ higher vulnerability due to their age and health conditions. It is also because many caregivers in these homes lack access to PPEs and are often overworked in often understaffed facilities. Being poorly paid, some of them also work in multiple facilities just to make ends meet. Poor working conditions of migrant workers in long-term and eldercare homes have been well documented by several studies – conditions regarding their work hours, allocation of responsibilities for diverse tasks and more difficult patients, low pay rates, and no overtime compensation.

Thirdly, the hundreds of thousands of migrant domestic workers who work in private homes are in the frontlines of keeping homes safe and clean. They face multiple risks as a result of the pandemic – health risks, more demands on their time, and income loss. According to the International Domestic Workers Federation, domestic workers worldwide have reported many concerns since the global pandemic began. With entire families staying home all day due to quarantine measures, domestic workers face heavier demands of cooking, cleaning, and caregiving without the benefit of additional pay for longer hours—and because of mobility restrictions, many cannot leave the homes where they work.

Finally, many care workers who have irregular migrant and/or employment status under informal arrangements have no access to unemployment and health insurance benefits, relief packages or financial aid related to COVID-19. This has been recently documented by the National Domestic Workers Alliance and the Pennsylvania Domestic Workers Alliance (networks representing nannies, caregivers and domestic workers in the US), the European Trade Union, and the Kanlungan Filipino Consortium in the UK. Those who fall ill prefer not to go to hospitals until it is too late for fear of being reported to migration authorities and because they do not have health insurance. These care frontliners are largely invisible and likely to suffer in silence

Contributed by Amy King-Dejardin, Former senior staff of ILO (Geneva) and author of the 2018 ILO report, “The Social Construction of Migrant Care Work.”

[1] King-Dejardin, A., 2019, The social construction of migrant care work, Geneva: ILO https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-migration/publications/WCMS_674622/lang–en/index.htm

*Learn more about the ILO Bureau of Gender Equality here

- Published in COVID 19, Migrant Care Workers