Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective

Below is an excerpt from a recent piece “Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective” by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group. This article was published by Migrants and Systemic Resilience: A Global COVID19 Research and Policy Hub (Mig-Res-Hub).

In this think-piece I consider how we can build a resilient systemic response to the COVID-19 pandemic and future crises. I focus on systemic resilience in relation to carework and global migration of careworkers, and I approach this from an Asia-Pacific perspective. One of the fault lines exposed by the COVID-19 is the vulnerability of the existing care, carework and migration infrastructure to exogenous shocks. Asia-Pacific is an important site to examine because it is one of the major sites of global care migration, both as sender and receiver of migrant careworkers. This think-piece draws on the research from our global partnership project based at the University of Toronto, which looks at the dynamics of careworker migration in Asia-Pacific and the interconnections between social and economic forces and policies in shaping those dynamics from both sending and receiving country perspectives. The next section briefly outlines the pandemic’s impacts on carework and care migration in Asia-Pacific. I then discuss how we might achieve systemic resilience in global care migration by first emphasizing how our care systems are interlocked with the global migration of careworkers (what I call a global care interlock), and second, how we might achieve systemic resilience. Understanding the global care interlock is an important prerequisite to systemic resilience because it allows us to see carework and migration of careworkers as a part of a larger global infrastructure or ecosystem that has been, consciously or unconsciously, built, managed and sustained by multiple actors in different parts of the globe.

Read the entire article here.

This blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing research for the Understanding and Measuring Care research group.

- Published in Asia-Pacific, Child Care, COVID 19, Elder Care, Migrant Care Workers, Understanding and Measuring Care

A Narrative on Care

In 2018, the Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) Project’s Understanding and Measuring Care (UMC) Working Group set out to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of care work and the well-being of caregivers in the context of South Korea. The group used a unique qualitative method combining in-depth interview and oral historical approach to investigate care as a continuously recurring activity throughout one’s life course and a necessary part of human existence. As part of the project’s qualitative field work and with the help of Gallup Korea, the UMC Working Group conducted 96 interviews between May – December 2018, bringing together 96 comprehensive narratives of care work in the South Korea context.

The CWE-GAM Project’s qualitative field work in South Korea conducted 96 in-depth interviews of paid and unpaid caregivers to provide useful care narratives based on the Korean context to inform macro-modelling. The qualitative research team interviewed 25 family caregivers of the elderly, 20 family caregivers of children, 20 paid care workers for elderly, and 31 paid care workers for children. The interviews of family caregivers focused on the decision-making process and evaluation of care arrangements for the elderly and children. In-depth interviews were combined with an oral historical approach to gain a deeper understanding of care work, emphasizing active listening to gain a more holistic understanding of the narrator’s life story on care. Interviewees were also asked about their experiences with caregiving. The interviews of paid caregivers focused on dual care burdens in terms of paid care work in addition to unpaid care work in the home. To learn more about the CWE-GAM Project’s qualitative field work in South Korea, read the Qualitative Methodology Report by the Care Work and the Economy UMC Working Group.

The following is one of the 96 stories. The respondent, Sung, lives with and cares for her mother, who was diagnosed with dementia about ten years ago.

*******************************

Date: May 29, 2018

Seocho-gu, Seoul

Interviewer: Hyuna Moon

Interviewee: Sung (pseudonym)

Sung, born in 1968, is 50 years old. She has a son and a daughter. They are both over 19 years old. One is attending college, and the other is studying for the college entrance exam. She is currently living with her children and her mother. As for siblings, she has one younger brother who is married. About ten years ago, Sung’s mother was diagnosed with dementia. Sung’s dad cared for her mom in the beginning, but her dad was also later diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Sung thus decided to move into her parents’ house to live together. It was by the time her first child entered middle school and her second child reached the upper grades in primary school. Her dad died four years ago, and she now looks after her mother. Her mother became a grade 3 beneficiary of the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTC) in her initial stage.

When Sung found out that her parents were ill, she didn’t think about passing the care duty to her brother. The siblings first considered making living arrangements so that each of them would live with one of their parents, for instance, Sung living with their dad and her brother living their mom, but their parents did not want this; they wanted to live together, not separately. Sung also felt that she ought to take care of her mother because of her ten years of experience living abroad, away from her parents. Sung has never thought that taking care of her frail parents is a son’s or a daughter-in-law’s duty. She didn’t think it was her brother’s duty to live with their parents and provide support. Nonetheless, her brother has taken up the role of financially supporting their parents. According to Sung, this was not negotiated but naturally happened. Sung and her brother also tried having their parents stay at her brother’s house during weekends, but it was always troublesome because he was not familiar with the situation, thus constantly calling up Sung for help. This weekday/weekend division of care duty did not work for them. Sung’s mother started going to the elderly daycare center from 2015 after her husband died. Her mother moved to a different center once because the center was located too far away from Sung’s place. Sung’s mother attended the first center for two years. When the center stopped running its shuttle bus to Sung’s house, Sung had to drive her mother to and from the center for a year. During that time, she had to hire a private caregiver who was responsible for driving Sung’s mother home in the evenings.

The hired caregiver also prepared meals and did some simple house chores for Sung. Sung paid her 1,000,000 KRW ($850 USD) every month, in addition to the monthly senior center fee of 300,000~400,000 KRW ( $250 – $335 USD). Other care-related expenses include Sung’s mother’s caregiver’s wage and other care services such as home-visit bathing service on weekends, food, medical bills and daily necessities such as diapers and etc., totaling about 2,000,000 KRW ($1,700 USD) per month. Sung’s brother helped to cover their mother’s care-related expenses, as Sung’s own income also had to cover her children’s education and living costs.

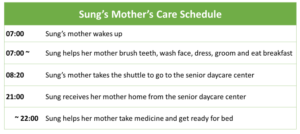

Description of Care Arrangement

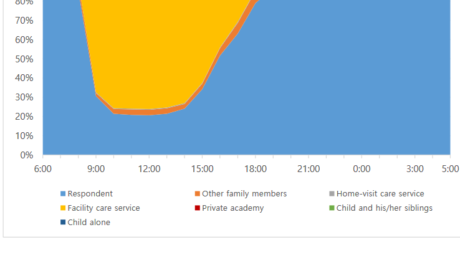

Sung’s mother goes to the senior daycare center on weekdays and receives a home-visit bathing service every Saturday morning. The current elderly care center runs a shuttle that arrives at Sung’s house at 8:20 am to pick up her mother and to ride her back home at 9 pm. Sung’s mother is using the center service fully, spending the whole day at the center. Sung takes care of her mother after 9 pm until she goes to bed. When her mother comes back home, Sung helps her take medicine and changes her clothes and diapers. Her mother sleeps before 10 pm. Sung said her mother usually gets home tired after engaging in a variety of programs and activities offered all day long at the center.

Sung thinks her mother’s enrollment at the day care center is better than her staying at home and being bored. Sung said the most difficult part in caring for her mother happens at night, when her mother wakes up due to defecation. In such instances, Sung has to respond quickly to avoid what would otherwise become an even longer night, with her having to clean up the remains that will be all over the place. It got worse since last year and called for the most attention when caring for her mother. Nevertheless, Sung said her mother’s situation of dementia is not too bad, considering that some people with dementia can be very aggressive and easily agitated. Sung’s mother is relatively well-behaved, but she has this stubbornness which makes it difficult for Sung to help her get washed and change her underwear for she finds these to be a shame.

Sung said weekend care is tougher than weekday care because she needs to prepare food for every meal. The LTC-funded caregiver visits every Saturday to provide bath support, which is of great help, but Sung also needs to partake in the bathing assistance, requiring her presence.

The Cost of Caregiving

For Sung, it was an overload of work when she started supporting her parents by living together, while also having to care for her two adolescent children and working for her job at the same time. Sung said she had suffered from depression a few years ago due to the high stress of managing all her responsibilities. She had to seek psychiatric and medical treatments to overcome her depression.

Sung is considering sending her mother to the 24-hour nursing home as her health status is gradually deteriorating. She has applied for the institution for her mother’s stay, but she faces a long waiting list with more than 200 people. Sung said the reason for such a long waiting list is because this is a public nursing home, which is believed to provide better quality care and facilities.

Two years, she said, is what she thinks as the maximum number of years that she would be able to live with her mother if the current situation holds. But if it worsens, that is, if her mother’s dementia symptoms get worse, Sung will also consider sending her mother to some other facility with a shorter waiting list but also with lower quality of care.

She said that she would have to set a deadline to her caregiving for her own sake. She does not want to spend the rest of her 50s trapped with the care duty to her mother. Her children are now independent adults. Sung wants to start living her own life. She also feels she has done enough for her mother, her families and relatives all know it, and nobody will blame her for making this decision. Sung said because she is also a human, she needs to have her life and has the right to pursue it instead of sacrificing for her family.

****************************

See the surveys utilized for conducting this research below:

2018 South Korea Eldercare and Childcare Household Survey – Childcare

2018 South Korea Eldercare and Childcare Household Survey – Eldercare

Care Work and the Economy: Fieldwork in South Korea

The 2018 fieldwork for the CWE-GAM project aimed to understand and measure care work in the South Korean context in order to inform gender-aware care macroeconomic models. The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys. The quantitative surveys include two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers in eldercare and childcare (Paid Care Worker Survey) and two sets of questionnaires for the unpaid care providers in the households for eldercare and childcare (Care Work Family Survey). The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and care recipients.

PAID CARE WORK SURVEY

The Care Work and the Economy Paid Care Work Survey includes two sets of questionnaires for eldercare and childcare workers and a 24-hour time use diary. A purposive sampling method was used to sample 600 paid care workers, 300 eldercare workers and 300 childcare workers, because the exact size and distribution of paid care workers in Korea are unknown. Paid care workers are defined as those working in institutional settings, at the care recipients’ home, and informal workers working without formal contracts. The sample targeted those providing care of the elderly and children’s daily lives, excluding kindergarten teachers and health care workers at hospitals and medical eldercare facilities. The sample of paid care workers associated with institutions were allocated to reflect the national distributions of eldercare facilities and daycare centers, and the sample of informal care workers were equally allocated across regions.

The Paid Care Worker Survey collected detailed and comprehensive information on the care work provided by paid care workers. The stylized questions and time use diaries of paid care workers collect information on the type, intensity, duration, and evaluation of care work from the perspective of paid care providers. The survey aimed to investigate the characteristics and working conditions of paid care workers, including their background, condition of contract, working environment, task arrangement, and subjective evaluation of the working conditions, and their well-being. The 24-hour time use diaries were collected to provide insights on how the day of a care worker is constructed and how care work is associated with other domains of daily life and time use, which can be analyzed in tandem with the stylized questions on the well-being of care workers.

FAMILY CARE WORK SURVEY

The Care Work Family Survey also consists of two sets of questionnaires for main care providers in the household engaged in childcare and eldercare respectively. 1,000 cases of main care providers in the household were interviewed (500 cases for childcare, 500 cases for eldercare) using a stratified cluster sampling method. Because it is not possible to know the distribution of the population of people who provide unpaid care in a society, children aged below 10 and the elderly aged over 65 were treated as the target population from which to draw the sample. Based on the distribution of the 2018 National Resident Registration Data in Korea, we allocated the number of target households to each area, identified eligible households with elderly or children in need of care, and then selected eligible respondents within the selected households.

The Care Work Family Survey was developed to provide a detailed and comprehensive picture of the care arrangements in South Korea. The survey aimed to investigate how care provision is arranged for the children and the elderly and why it is arranged in such ways. Therefore, the survey collects information from the main care provider, not the care recipients themselves, as it is often the case that the main care provider is the one who knows most about the care arrangements.

After screening for eligibility, respondents were asked questions on their demographic characteristics and information on the respondent, care recipients and other household members. Respondents were asked about the specific activities involved with their care work including frequency, subjective intensity, preferences and willingness to engage in the activities. Information on care arrangements were collected as well including how the care work is shared within the household, whether there are any gaps of care provision, the history of caregivers, use of care services, and decision-making of using care services. Other information such as financial responsibility and burden, experience and evaluation of care work, dual care burdens and well-being of caregivers were collected.

IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

The purpose of the in-depth interviews of paid and unpaid caregivers was to provide useful care narratives based on the Korean context to inform macro-modelling. The qualitative research team intervened 25 family caregivers of the elderly, 20 family caregivers of children, 20 paid care workers for elderly, and 31 paid care workers for children. The interviews of family caregivers focused on the decision-making process and evaluation of care arrangements for the elderly and children. Interviewees were also asked about their experiences with caregiving. The interviews of paid caregivers focused on dual care burdens in terms of paid care work in addition to unpaid care work in the home.

SIGNIFICANCE AND LIMITATIONS

The fieldwork for paid and unpaid care work in Korea was designed and conducted to investigate the nature and context of care work in Korea. The Paid Care Worker Survey and Care Work Family Survey have distinct characteristics that contribute to enhancing our understanding about the experience of caregiving in Korea. First, the set of questions that have been developed can be commonly applied to caregivers regardless of the type of care work or the subject of care to enable comparative analysis on the experience of caregiving. Second, not only the caregiving situation, but also the broader aspect of the caregiver’s life including the preferences and attitudes of the caregiver have been studied. Third, the surveys collect detailed information on how care is arranged. Lastly, a caregiver focused 24-hour time use diary has been developed to understand which activities could be considered as care.

This fieldwork only included certain types of caregivers due to the limited budget, time, and scope of the fieldwork. For instance, the sample did not include caregivers for the disabled, caregivers who work at hospital settings, and migrant care workers, despite their importance. Also, as the family survey for childcare limited the respondents to ‘mothers’, and consequently fathers and grandparents were excluded. We hope that the future rounds of surveys can be extended to have a larger sample size and to include a broader range of caregivers. Questions explored in this fieldwork provide important information about the experience of caregiving in Korea, and we hope the fieldwork in Korea can inform fieldwork in other countries.

Learn more about care arrangements and activities in South Korea based on our analysis on the 2018 Care Work and Family Survey here.

This blog was authored by Bong (Regina) Sun Seo, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group

Glimpse of Family Caregivers’ Context: Actual time vs. Desired time for Care

Attitudes towards family care are changing. Only 27% of Koreans surveyed in 2018 agreed that the family is responsible for elderly family member care. As for population aging, the middle age group of Korean society is becoming a true “Sandwiched Generation” (supporting both unmarried children and elderly parents) due to the longevity increase among elderly parents and postponement of marriage among the young generation. In addition, caring for grandchildren by the young elderly group is becoming more prevalent as the number of employed married women has increased in recent decades. To respond to this family burden, Long Term Care Insurance for the Elderly (LTCI) has been expanded since 2008. Statistics of the LTCI program show a stiff increase in care provision for supporting the daily lives of elderly who suffer from physical and mental ailments.

Cha & Moon (2019) investigate the nature of family care in the context of expanding public care provision. Using the 2018 Family Survey for Child and Elder Care, the authors assess the role of family care and how family members take part in the changing elderly care process. Family caregivers spend, on average, about 8 hours a day providing care to elderly family members on caring days, or about 50 hours a week. However, the average preferred number of hours for care is 24 hours per week, almost half of the actual care hours. Those who are classified as mildly or severely over-caring tend to live with their elderly family member, partly because the elder family member has a severe limitation in their Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and is unlikely to spend more than 3 hours per day alone.

On the other hand, care givers whose hours matched their desired hours are relatively young and the employment rate is higher than among other types. Compared to this matched case, over-caring is more common when attentiveness is required, when the caregiver perceives the necessity to take on greater responsibility for the elderly care recipient, and when time consuming care tasks are needed to care for the elderly family member. The authors speculate that the different types of care arrangements—under-caring, matched, and over-caring—appear to represent the sequential process of elderly care, from making regular care-visits to constantly ‘being there’ next to the recipient.

This paper will be available December 2019.

Family Caregivers’ Elder Care: Understanding Their Hard Time and Care Burden

In response to the imminent aging problem in South Korea, the National Long-Term Care Insurance (NLTCI) system was introduced in 2008. The goal of the NLTCI was to give support to the families who are taking care of their elderly. The burden of family care can be grouped into four broad categories – unpaid and at home, paid and at home, paid and in facility, and unpaid visit of the family when care recipient is in facilities. Moon et al (2019) focus on the challenges faced by providers of unpaid care within families – unpaid care by family members is the most prevalent form of elderly care in Korean society.

Korean’s attitudes or thoughts on the family care responsibility of their old parents have changed surprisingly as time passed. In 1998, 89.9% of Koreans agreed with the idea that the care responsibility of their old parents belongs to the family. In 2014, the figure dropped to about a third of the population – only 34.1% of surveyed adults agreed to share the responsibility. The authors take this trend and generational gap as the departure point for their qualitative analysis of the difficulties faced by caregivers, with a view that there might be a clash or inconsistency in the care behaviors of the family members or in their ways of thinking on elderly care.

Using a combination of oral history and in-depth interviews, Moon et al (2019) shed light on the increasing burden of labor force participation and aging parents and in-laws on Korean women. Many elderly persons need attention and care continuously for 24 hours – in this regard the public care service providers provide limited relief as they work for only three hours at a time. In addition to the public-private and paid-unpaid differences in the burden of care, the authors draw attention to the difficulty of deciding who in the family takes up the responsibility. In many cases, the traditional caretaker roles fulfilled by the daughters-in-law have shifted to the daughters of the elderly. Social norms also contributed to the disproportionate caretaking burden borne by women.

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

Care Arrangement and Caregiving Activities in South Korea: An analysis of 2018 Care Work Family Surveys on Childcare and Eldercare

The rise of the care crisis in South Korea has evolved with Korea’s demographic shifts, increasing female work force participation, and changes in the norms and values of family and care over previous decades. Childcare and eldercare, once regarded as women’s typical role within family, are now gaining more social recognition in the public realm. Kang and Eun (2019) examine the nature of, and demand for, caregiving in various areas of the South Korean economy, including family care, care services, childcare and eldercare. The study is based on the nationally representative Care Work Family Surveys on Childcare and Eldercare.

The authors find a significant gap between the number of hours spent on childcare by mothers and fathers. A majority of respondents (women) used at least one external care service. Among caregiving activities, housework such as preparing meals, cleaning, and laundry were reported as the most difficult as well as the most frequently performed activities. Relational and physical activities such as helping to dress, wash, or play with children were reported as less difficult. Caregiving for the elderly can be more complex compared to care arrangements for children, because the range of participants in the family varies. Among all respondents, daughters-in-law were the primary caregiver in the greatest number of cases, followed by daughters, spouses, and sons. Spouses spent the highest number of hours on caregiving, followed by daughter in laws. External care services were not as common for elderly care. Home visit care and home bathing services from the National Long-Term Care program were the most commonly utilized services, although the 3-hour limit per visit amounts to a low amount of total caregiving time. Assisting with bathing and using the restroom was considered especially difficult for the elderly. Housework was performed with the same intensity and frequency in both childcare and eldercare, highlighting the important role it plays in both.

This paper will be available December 2019

This blog was authored by Eunhye Kang and Ki-Soo Eun

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

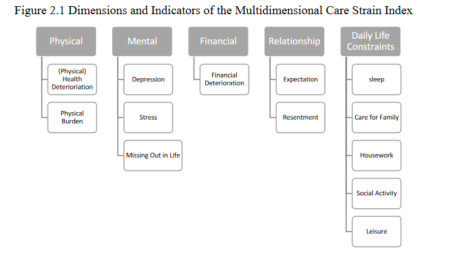

Measuring the Overall Strain of Caregiving: A Multidimensional Approach

Providing care for others, especially for the frail elderly and young children, is one of the most important forms of human work that sustains our existence. However, caregiving is also often challenging and strenuous. Many informal caregivers are known to suffer negative physical, emotional, and social outcomes, and are at risk of losing their own health and well-being. Fengler and Goodrich, for example, refer to the wives of frail elderly men as ‘the hidden patient,’ warning the negative consequences of caregiving on informal caregivers. Since the 1980s, several instruments have been developed to measure the strain of caregiving among informal caregivers. Some measurements such as the Zarit Burden Interview and the Caregiver Strain Index have been applied more widely, while other measurements have been used for more specific groups of caregivers (e.g., who takes care of the elderly with cancer). Although these measures provide valuable information on various dimensions of caregiver strain, they are not sufficient to assess the overall level of strain experienced by caregivers. In most cases, these measurements consist of a list of questions or statements about the caregiver’s burden; the sum of the answers is then used to indicate the level of burden/strain experienced by the caregiver. Although useful, a simple non-weighted sum of answers may not be an accurate representation of the overall strain. For instance, two groups of caregivers may have the same average total strain score, but one group may consist of all caregivers who suffer strain in some statements, while the other group may have half of the care givers who suffer strain in all statements and the other half who do not suffer strain at all. While the marginal distribution may be the same, the joint distribution may not, and this has an important policy implication.

Adapting the Alkire-Foster method developed to measure multidimensional poverty, Jun et al (2019) propose a threshold-based approach to measuring overall caregiving strain that accounts for the multidimensionality of the caregiving experience. The approach is based on the premise that as in the case of poverty, the negative consequences of multiple strains attached to caregiving would be greater than the sum of their individual effects. The authors first identify the dimensions and indicators that are known to be important consequences of caregiving, such as physical, psychological, financial and relational strains, and daily life constraints. They then count the overlapping strains a care giver experiences under different indicators of caregiver strain. Next, they identify caregivers who are experiencing strains above a specific cut-off point as multi-dimensionally strained. This measure is tested using the data from the newly collected Survey of Eldercare and Childcare in Korea 2018, exploring whether receiving support, help and appreciation may be associated with reduced chance of being multi-dimensionally strained. By providing an overall measurement that identifies caregivers with multiple strains, the authors examine 1) which group of caregivers are more likely to be at risk; 2) which dimensions do most caregivers suffer strain; and 3) what may be potential buffers for caregiving strain.

This paper will be available December 2019

This blog was authored by Jiweon Jun, Ki-Soo Eun and Ito Peng

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care