Climate Change and COVID-19: Why Gender Matters

This article was originally published in the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs on July 9, 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the important intersections of climate change, food security, migration, and socio-economic inequalities. An understanding of the gendered dimensions of these interconnected global concerns is crucial for developing a post-COVID recovery plan that ensures a more equal world and bolsters its resilience.

In many ways, the year 2020 spotlighted the compounding issues societies must reckon with, including climate change, COVID-19, and sustained inequality. Today, we are witnessing the drastic consequences of climate destabilization resulting largely from human actions: frequent heat waves, intense flooding and droughts, water crises, increased biodiversity loss, reduced agricultural productivity, and faster disease transmissions. Many of these underlying causes of climate change also increase the risk of future pandemics. For example, deforestation leading to loss of animal habitat forces animals to migrate and brings them into closer contact with other animals or people, increasing the likelihood of zoonotic transmission.

The effects of climate change are being felt throughout the world; its worst impacts are particularly damaging in poorer regions, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia. Severe and prolonged droughts have already affected the Sahel and most of East Africa. Meanwhile, severe storms and flooding are causing extensive damage across the world, and climate change-related food insecurity has resulted in thousands of deaths. Climate change has also intensified water scarcity, reaching critical levels in seventeen countries. Major rivers no longer reach the ocean, while reservoirs and lakes dry up and underground water aquifers are depleted. As climate change continues, drier areas will only be more prone to drought and humid areas more prone to flooding. As food, water, and other resources become increasingly strained, fierce competition over scarce natural resources is likely to escalate. In fact, natural disasters and climate-related conflicts have already dislocated millions of people. In 2017 alone, the UNHCR estimates about 30.6 million new displacements associated with conflicts across 143 countries and territories.

Making Gender Visible in Climate Change Issues

It is fundamental to note that these aforementioned issues are gendered. Gender disparities in access to resources such as land, credit, and extension training have put many women at greater risk with regards to maintaining their livelihoods and accessing food and water. Climate change not only reflects pre-existing gender inequalities, but it also reinforces them. The pivotal role of women in food security is well-documented. Recent estimates for Africa indicate that women provide 40 percent of labor in crop agriculture while at the same time providing labor in small livestock, poultry, and other food production-related activities. Many are income earners, serving as breadwinners in female-headed households while performing most of the household and family care work. However, gender inequalities in the ownership and control of household assets, gender discrimination in labor markets, and rising work burdens due to male out-migration undermine women’s income generating capabilities. Much of women’s work in food production and food access remain statistically invisible because conventional economic indicators fail to capture the significance of their contributions—contributions that are also overlooked in policymaking.

The gendered consequences of climate change include effects on migration flows. Migration has diversifies livelihoods and serves as an important coping mechanism through the promise of remittances or a better life. Internal and international migrations involve individuals and families seeking protection as refugees from the violence in their communities and states and those whose livelihoods are threatened by natural or man-made factors such as natural disasters, economic crises, or political instability. More recently, the increased frequency of extreme weather events and high temperatures have led to climate-induced migration flows exemplified by the influx of climate refugees seeking entrance into the United States in response to hurricanes, and rural-urban migration in Vietnam in response to typhoons.

The ability of households and their members to relocate varies depending on their resources and their vulnerability to the risk of falling further into poverty. Both the gendered dimension of migration and the climate shock impact on migration decisions are nuanced. Migration can challenge certain social expectations and cultural norms. Household care responsibilities and gender roles may restrain women from migrating. In the case of increased conflicts over natural resources, for instance, women are less able to flee than men as they are often responsible for taking care of the children. In Indonesia, climate shocks have promoted more migration among men. Similarly, male migration in Ethiopia and Nigeria has increased with drought and weather variability, while women are forced to stay put due to financial constraints. On the other hand, increasing demands for care workers in countries with high female labor force participation and aging populations provides employment opportunities for women, fueling international migration flows. In 2019 alone 48 percent of the 272 million (3.5 percent of the world’s population) international immigrants were female.

Gender and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The trends in climate-induced problems have foreshadowed the severity of the crises induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has affected all aspects of everyday life and work and has placed a heavy toll on families, communities, and economies. It threatens food security for tens of millions of people. The COVID-19 crisis, like the climate crisis, is causing disparate impacts across nations and social groups. It poses a much greater risk to elderly persons and those with underlying risk factors. Countries with fewer economic resources and weak social and health infrastructure are at a higher risk, not only in the short term but also in the longer term. Politically underrepresented groups suffer the most from lockdowns, rising unemployment, and unexpected medical costs, exacerbating existing economic inequalities.

More importantly, the COVID-19 crisis also unravels and further amplifies gender inequalities. As millions of people lose their jobs or become forced to work from home, many, especially mothers, are compelled to simultaneously juggle work and childcare responsibilities. Unpaid care work has increased not only with children out of school but also with the heightened care needs of the elderly and the sick, especially when health services are either inaccessible or overwhelmed. Ultimately, many women are earning less, saving less, working precarious or insecure jobs, or living close to poverty.

Gender-based violence is rapidly increasing as well. Many women are being forced to “lock down” at home with their abusers at a time when support services for survivors are being disrupted or made inaccessible. In Peru, the imposition of lockdowns has led to a 48 percent increase in phone calls to the helpline for domestic violence.

The COVID-19 pandemic also exposes the precarious employment conditions of many “essential workers” whose jobs increase their risks of infection and are often employed on temporary contracts. Migrants are among the key workers who deliver essential services; they play a critical role in essential sectors in many high-income countries working as crop pickers, food processors, care assistants, and cleaners in hospitals. These migrant workers help facilitate systemic resilience to threats, but their own vulnerabilities go unaddressed.

Conclusions

We cannot afford to ignore the particular vulnerability of women when analyzing the effects of climate change on food security and migration, and we cannot ignore their susceptibility to food insecurity and violence. As governments and policymakers grapple with the challenge of bolstering resilience, they will need to think beyond the effects of these shocks on markets and to pay more attention to the heightened social and economic inequalities. Such an objective requires a comprehensive, gendered approach that considers women’s roles in the provision of essential goods and services and the differentiated impacts of climate change.

Fiscal stimulus packages and emergency measures have been put in place by many countries to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19, but it is crucial that these responses as well as post-COVID recovery plans put women and girls’ interests and needs, rights, and protection at their center. Such responses and plans should include expanded public investment in the care delivery system, from childcare to healthcare to eldercare, which the COVID-19 crisis has disrupted. There is also a need for gender-sensitive analyses of the effects of economic, social, and migration policies along with the development of legal frameworks that effectively address domestic violence. Meaningful participation of women in policy discourse and dialogue addressing climate change is vital as they are disproportionately vulnerable.

Governments should also undertake and support the collection of sex-disaggregated data on various economic, social, and climate-change related indicators as the lack of data is sometimes used as an excuse not to implement gender-responsive policies. As UN Women has stated, “it is not just about rectifying long-standing inequalities but also about building a more just and resilient world.”

This article was written by the CWE-GAM Project’s Principal Investigator Maria S. Floro and was originally published in the Georgetown Journal for International Affairs on July 9, 2021.

- Published in COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy, Maria Floro, Policy

“Girly Issues” Are Now the Country’s Issues

Dr. Nancy Folbre, an Advisor and Researcher of the CWE-GAM project and a groundbreaking feminist economist was among the first to sound the alarm about the care crisis. Dr. Folbre’s work on the care sector, once considered “just girly issues” by fellow economists, are now recognized as issues belonging to the U.S.. Previously the recipient of the 1998 MacArthur “genius” grant, Dr. Folbre’s research has journeyed from “fringe idea to more mainstream policy.”

Once cast aside in policy discussions, the care crisis is finally getting the spotlight it deserves after the pandemic forced many schools and child-care centers to close, leaving “ten million mothers of school-age children out of the workforce.” The pandemic is forcing policymakers to finally face the cracks in America’s care infrastructure that Dr. Folbre and other experts have long pointed out— “a system where working parents do not have reliable, affordable child care is one where they cannot reliably build a career.”

To learn more about Dr. Folbre’s work on care, visit her blog Care Talk and read her recent book The Rise and Decline of Patriarchal Systems.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics

Making Care Count

The COVID-19 pandemic has informed our understanding of the care economy, exposing disproportionate inequities that must be addressed to alleviate the international erasure of care workers. These issues are addressed in the latest Susan and Michael J. Angelides Lecture, in which Naomi Klein moderates a discussion between Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal and CWE-GAM researcher Dr. İpek İlkkaracan on COVID-19 and the care economy.

We live in an economic system that has traditionally deprioritized and invisibilized care workers, many of which are women of color, migrant, and poor women. The economic crisis brought on by the pandemic has consequently given policymakers and academics “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address [the valuation of care work] from an intersectional [approach],” states Congresswoman Jayapal.

The Care Crisis Exposed by the Pandemic Recession:

When mass unemployment hit during the pandemic, the cracks in the economic infrastructure of America began to show. As millions of people lost their jobs, the highest increase in the number of uninsured Americans was subsequently recorded. This high number of uninsured people is a direct consequence of healthcare being employer-sponsored. Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “Medicare For All would have strengthened the response to the pandemic…30 percent of COVID-19 deaths were related to a lack of insurance.”

While gains were made in the past decade in regards to gender equality in the workplace, Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “as soon as the pandemic hit, it was the women who went back to taking care of [their] families.” Dr. İpek İlkkaracan explains that this is because “the nature of women’s employment is often determined by their care responsibilities…unpaid care work is often articulated as one of the most significant barriers to labor force participation.” This notion was reflected in jobs reports—in December of 2020, women accounted for 100 percent of job loss, and within that, 154,000 Black women exited the workforce.

In its current state, the care economy produces a pattern of inequality that disproportionately affects women of color and migrant women. The average caregiver salary is $12.74, and the care work sector is marked by poor working conditions with no adequate social protections and low wages. This is why, as Congresswoman Jayapal notes, the fight for one fair wage is pertinent. “An increase in the minimum wage would give 32 million workers a raise, 60 percent of which are women while 1 in 4 of the women who would benefit from this increase are Black or Latina.”

A Framework for a More Caring Economy:

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan has developed a framework that acknowledges the care economy. This framework, coined as the Purple Economy (a nod to the color representative of many women’s movements), envisions a gender-egalitarian and caring economic system. Dr. İlkkaracan recommends “labor market regulations and investment in care services such as long-term care, early childhood education, education, and healthcare” as policy interventions to start the process of adequately valuing care.

Not only is investment in care important from a humanitarian and ethical perspective, but it is also conducive to economic stability. Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has revealed that investment in care services produces a high employment multiplier: for every dollar invested in care, three times as many jobs are created in the wider economy. This is because the care sector is intertwined with other sectors such as food, transport, and financial services. In the Asia-Pacific region, Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has shown that “up to four trillion dollars could be added to GDP if unpaid care work (75% of which done by women) was valued in market terms.” While this may seem astronomical, the amount of unpaid work completed globally in one day equates to 16.4 billion hours—which translates to two billion full-time jobs. Dr. İlkkaracan’s recent research also reveals that a “3.5-4% commitment of GDP to investment in care services would create 120 million additional jobs and have a large impact on poverty alleviation.”

To watch the full conversation and learn more about the Purple Economy, see below.

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan is a CWE-GAM researcher a part of the Rethinking Macroeconomics and Gender Aware Applied Economics Working Groups.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Gender-Equal Economy, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, U.S.

Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective

Below is an excerpt from a recent piece “Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective” by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group. This article was published by Migrants and Systemic Resilience: A Global COVID19 Research and Policy Hub (Mig-Res-Hub).

In this think-piece I consider how we can build a resilient systemic response to the COVID-19 pandemic and future crises. I focus on systemic resilience in relation to carework and global migration of careworkers, and I approach this from an Asia-Pacific perspective. One of the fault lines exposed by the COVID-19 is the vulnerability of the existing care, carework and migration infrastructure to exogenous shocks. Asia-Pacific is an important site to examine because it is one of the major sites of global care migration, both as sender and receiver of migrant careworkers. This think-piece draws on the research from our global partnership project based at the University of Toronto, which looks at the dynamics of careworker migration in Asia-Pacific and the interconnections between social and economic forces and policies in shaping those dynamics from both sending and receiving country perspectives. The next section briefly outlines the pandemic’s impacts on carework and care migration in Asia-Pacific. I then discuss how we might achieve systemic resilience in global care migration by first emphasizing how our care systems are interlocked with the global migration of careworkers (what I call a global care interlock), and second, how we might achieve systemic resilience. Understanding the global care interlock is an important prerequisite to systemic resilience because it allows us to see carework and migration of careworkers as a part of a larger global infrastructure or ecosystem that has been, consciously or unconsciously, built, managed and sustained by multiple actors in different parts of the globe.

Read the entire article here.

This blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing research for the Understanding and Measuring Care research group.

- Published in Asia-Pacific, Child Care, COVID 19, Elder Care, Migrant Care Workers, Understanding and Measuring Care

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part II

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” The discussion describes the interconnections between the crisis of care, the deepening ecological crisis and growth and accumulation processes.

There are many common threads with the climate and ecological crisis and the care crisis. Significantly, the idea that economic growth is overall beneficial. The type of economic growth generally pursued worldwide has not only increased stresses put upon the earth’s resource base but also on care labor capacity, which is similarly but wrongly perceived to be of infinite supply. Moreover, arguments that equate economic growth with overall improvement fail to recognize the distributional element of rising income inequality, which is far more nuanced. In fact, among countries that are higher income, gains from economic growth within those nations do not trickle down to everyone. When looking at care, the widening income equality gaps has shifted distribution of care givers across social classes and national boundaries. As a result, the quality and adequacy of care within a single nation can be very different, which exacerbates differences in social reproduction.

At the same time, income inequality has created a solution for the care needs of those that have the means to hire care for children and elderly, because care workers in those sectors are often paid low wages. But for the working poor, hiring care work help is inaccessible due to financial constraints, therefore they rely on their kinship networks to help provide this care. Furthermore, much of the care work burden still falls on women even as they enter to labor force. Economics and social policy in many parts of the world continue to neglect the heavy work burden put upon women and the necessity to balance household care activities and market work. What can also be observed is a global care supply chain, with the migration of women and girls to urban areas to provide care for wealthier families. Care itself is becoming one of the drivers of income inequality.

The economy is not all about material production; it is really about human vision and social provisions. However, an illusion has been created that unpaid care work is a natural resource that serves as an input for market production to promote GDP growth. However, this idea does not take into account that the wellbeing of people, especially the elderly, the sick and children should be an end in and of itself, to achieve sustainable growth. There is much work to be done to address these issues. To begin, economists must envision long term horizons that look forward to future generations while also taking into account the interdependence of life and moral responsibility. They must also integrate care and environmental consequences into our economic policy tools. Overall a new economic paradigm that includes green ecology and feminist economic concerns is needed.

Link to Part 1 of this blog here.

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part I

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” This discussion delves into the foundation of project itself, its context, the analytical tools utilized in the research, as well as the external factors that have served as the catalyst for the work being done.

The Care Work and the Economy Project was developed after a group of feminist economists observed that in the effort to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes, as laid out within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, there were aspects of care work that needed to be addressed. The project includes 35 scholars from all around the world that are working to develop innovative analytical tools. The research has been applying and testing these tools in South Korea, a country that quickly industrialized in the 70s and 80s and therefore witnessed a very rapid demographic change in fertility and life expectancy.

The care economy, which is inclusive of caring for those that cannot care for themselves, underpins the production of all economies within society. This begins with the fact that if people stopped having children, which require care, then the economy would come to a halt due to lack of labor force. Generally, care work has a tendency to be undermined through a lack of gender awareness in macroeconomic modeling, which does not address care needs in any adequate manner. This aspect is also neglected within the policy making discourse, with the current economic paradigm failing to take into account the necessity for care work to achieve economic growth.

Economic models that display growth also fail to take into consideration social elements, making the assumptions that, for example, children will be cared for despite the lack of social investment into care. However, with care work there comes social, political and economic significance. The Care Work and the Economy project is working to demonstrate what a care focused macroeconomic model can reveal through the implementation of the analytic tools being developed and implemented through the research.

The absence of the care economy within macroeconomic models is in large part due to it being “invisible” since the work often unpaid. This has led to the neglect of care needs despite unpaid care work providing indispensable services in terms of economic activity and growth. The result is an emerging care crisis that has manifested itself in terms of uncared for elderly, sick and children. Furthermore, the crisis has provoked a form of silent protest against long unpaid work hours performed by women, leading to a decline in marriage and fertility rates. This in turn has resulted in a reproduction crisis.

The Care Work and the Economy project researchers are developing and using innovative analytical tools to bring care to the forefront, along with a deeper understanding of the nature of care work, while illustrating the intersectionality between care provisioning, economic growth and distribution. Although these analytical modeling tools are currently being applied in South Korea, the project believes they can be adopted and implemented into other countries as long as the provision of care is taken into context of those countries. The project research shows that governments have an important role and duty to invest in care provisions as well as comprehensive national care plans. One of the key findings is that it is important to take into account demographic change and climate change along with economic and structural changes taking place in policy making. This is a tall order but necessary to sustain economies and provide a future for next generation.

Link to Part 2 of this blog here.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

Hawai’i and Canada Provide Lessons for Feminist Economic Recovery from COVID-19

The need for an inclusive, gender-equitable recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is slowly gaining recognition as it lays bare and exacerbates inequities in economic, social, health, and environmental policies and programs.

The Hawai’i State Commission on the Status of Women convened a working group to develop and share principles and practices for implementing a gender-responsive and feminist response to COVID-19, culminating in the publication of Building Bridges, Not Walking on Backs: A Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for COVID-19.

Similarly, the YWCA Canada and the Institute for Gender and the Economy (GATE) at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management published a joint assessment, A Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for Canada: Making the Economy Work for Everyone. The plan highlights critical principles and provides actionable recommendations for the government to develop and implement post-pandemic recovery policies that are equitable and inclusive of all marginalized people.

Together, the Canadian and Hawaiian plans provide a roadmap to recovery through gender-transformative policy-making. Both are built on an intersectional analysis of the impact of the pandemic and call for an approach to economic recovery that examines and confronts the root causes of inequality, including but not limited to patriarchy, ableism, queerphobia, white supremacy, colonialism, classicism, and racism.

A recent brief by Alexandra Solomon, Kate Hawkins, Rosemary Morgan of the Gender and COVID-19 Working Group describes the intersecting, complementary, and mutually reinforcing elements of the two frameworks and echoes the call for feminist economic recovery. It provides a collection of best practices for the core tenets of post-pandemic policy-making which should be echoed and adapted by policy-makers from other settings.

Key Recommendations to Policymakers:

- Pandemic responses should be underpinned by data that is disaggregated by sex and other markets of inequity at the national and subnational level. This data should be made public and used in decision making.

- Women-led organizations, feminist academics and women’s experiences and ideas should be at the center of recovery efforts in government bodies, official consultations and online spaces.

- The provision of universally accessible, free childcare and long-term eldercare should be central to economic recovery plans and attempts to ‘open up’ the economy. Precariously employed immigrant care workers should be provided with an expedited path to permanent resident status.

- Austerity-induced budget cuts should be avoided as they impact most greatly on the poor, women and other marginalized groups. Instead policy-makers should strengthen public welfare assistance (such as unemployment benefit) and labor rights (such as paid sick leave, family leave and a guaranteed living wage).

- Special stimulus funds should be designated for high risk groups, such as those who are not eligible under existing government schemes, are disproportionately experiencing financial hardship and poverty, and already face barriers to accessing their rights to health, safety, independence and education.

- Invest in universal, affordable, and sustainable access to water, sanitation, hygiene and housing, and prioritize closing the gender digital divide.

- Support women in female dominated economic sectors particularly hard hit by the pandemic as well as historically marginalized women workers, such as Indigenous women and sex workers.

- A feminist recovery is aligned with a ‘green’ recovery and the two should be considered in conjunction.

- Revisions of fiscal and monetary policies should be taken as opportunities to address inequality in wages, employment, and quality of life.

- Health systems should be restructured to focus on Universal Health Coverage and to address problems in service access and quality due to sexism, colonialism and white supremacy. Tackling the social determinants of health should be a priority.

- All hate, violence, and oppression against women, gender-diverse people, and Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities must be addressed in the COVID-19 recovery.

READ FULL BREIF:

Solomon, A., Hawkins, K., and Morgan, R. (2020). Hawaii and Canada: Providing lessons for feminist pandemic recovery plans to COVID-19.The Gender and COVID-19 Working Group.

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in COVID 19, Policy, Policy Briefs & Reports

COVID, the Old and Canada-What’s Wrong With Us? A Massey Dialogues Discussion

A recent virtual presentation from Massey College, “The Massey Dialogues: COVID, the old and Canada – What’s wrong with us?” brought together a panel to discuss how the detrimental impacts of COVID-19 in Ontario and Quebec fall alarmingly onto the elderly population. In fact, 80 per cent of pandemic deaths in Canada have occurred among the institutionalized elderly, the highest proportion in the world.

Ito Peng joins this conversation as a special guest to discuss the pandemic and its impact on Canada’s Long Term Care (LTC) sector, and ways through which the dominant thinking around market value/productivity neglects to value the work that older adults have already contributed to the economy throughout their lives, and fails to recognize their role as keepers of history and caretakers themselves.

In this discussion, Ito Peng is joined by Massey Fellows Dorothy Pringle, Husayn Marani and Michael Valpy.

- Published in COVID 19, elderly care, Expert Dialogues & Forums

Digital Forum on Reopening Long Island and Building a Fair Economy:Care Work in the COVID Crisis

Earlier this month, the Hofstra Labor Studies and the Center for the Study of Labor and Democracy in collaboration with Long Island Jobs with Justice and A.L.L.O.W. (Advancing Local Leadership Opportunities for Women) conducted a virtual forum addressing care work in the context of COVID-19. This discussion emphasized the financial and mental health challenges associated with all types of care work during this pandemic, and the immense need to address and resolve these issues in order to assist with a fair and sustainable economic recovery. Although the discussion is focused primarily on Long Island and New York, the problems indicated are applicable to care work throughout the U.S.

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that the unemployment or the stress of juggling work and home life as a result of the crisis has hit women much harder than men. This discussion utilized academia as an example of this, drawing upon data indicating that academic journal submissions have greatly increased among men since the beginning of the pandemic, but sharply decreased among women. For those working in academia, publishing work is crucial to professional advancement.

The pandemic has also shed a harsh light on the fragility of the overall childcare system in the U.S. Many families lacked adequate childcare even before the pandemic, forcing them to rely on unpaid care work. These existing issues paired with the recent closures of childcare facilities has exacerbated the problem.

Although the CARES Act did include childcare support, New York receiving $164 million going toward the childcare industry to provide protective equipment and cleaning supplies, the panel argues that while helpful those measures still did not provide adequate relief. The HEROES Act could potentially provide further relief for the care industry, but participants of this forum are less than optimistic about it providing the level relief needed.

The International Labor Organization estimates that three-quarters of unpaid care worldwide is provided by women. In the U.S. women provide 37% more unpaid care work than men on a daily basis. Among care providers in the U.S., Hispanic women do the majority of unpaid care and account for the biggest gap among men and women. Beyond traditional gender roles, this is largely tied to economics; oftentimes men have opportunities to make more money. But generally speaking, even when both parents work full time, women are still taking on more unpaid work even if they are earning more money than the male figure within the household.

There is also a societal tendency which expects care workers to be exceptionally giving. This is highlighted in the fact that even within paid care work positions, there is a fair amount of unpaid work being performed. For example, staying with an elderly person at their doctor’s appointment a couple of hours after the official workday has ended. This is a constant strain within the care industry, and COVID-19 has increased the pressure on this component of unpaid work within the paid care industry.

Additionally, the many racial and ethnic disparities within care work serve as a microcosm of larger racial inequities prevalent in society. For example, in New York, 80% of care workers are women, and a large majority of them are women of color. Furthermore, care workers in New York typically make minimum wage yet are still known to go above and beyond in their roles to ensure the best care is provided, regardless of whether or not it is part of their job description. This existing issue has been pushed to a new level due to COVID-19; now many of our care workers are putting their lives on the line.

Part of the reason that low wages are prevalent within the care sector is the historical association that care work is a “women’s job,” coming naturally and requiring little skillset. This sentiment in the U.S. is compounded by care work being viewed as the responsibility of the individual. The decision to have a family is viewed as a personal choice, therefore the basic needs of childcare are the sole responsibility of the parents, not something to be addressed via larger social safety nets.

New York is facing a particularly troubling dilemma within its care work industry. Despite the fact that a large majority of the workforce is comprised of immigrants, the guidelines that have been released outlining protection measures from COVID-19 are only available in English. This is concerning given that some workers may not yet possess the English language proficiency necessary to fully comprehend these guidelines.

In order to address these strains within the care work industry, political will and national policy are needed. The U.S. Department of Defense provides an exemplary model that could be emulated on a national scale. This government sector presently has one of the best childcare systems available in the U.S., operating on a sliding scale making it accessible to all those within the department that need it. This allows these federal employees to perform their duties with the comfort of this social safety net.

Furthermore, at the local level, immediate state, and county-level funding for care work can have a significant impact on the accessibility needed during this stressful time. Without swift action on the policy level, the issues discussed will continue and have detrimental effects on not only families, but economic recovery as well.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in COVID 19, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy, U.S.

COVID-19 AND THE CARE ECONOMY: UN Women calls for immediate action and structural transformation for a gender-responsive recovery

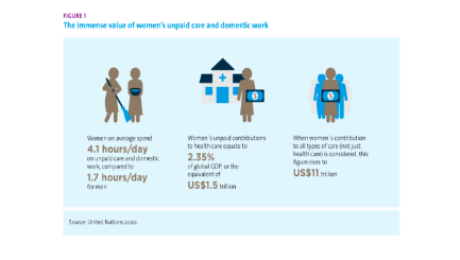

A recent brief from UN Women presents emerging evidence on the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic on the care economy.

Evidence suggests that the rising demand for care in the context of the COVID-19 crisis and response will likely deepen already existing inequalities in the gender division of labor, placing a disproportionate burden on women and girls. Not only are women over-represented among paid health care workers, girls and women also shoulders the bulk of unpaid care and domestic work that sustains families and communities on a day-to-day basis.

School closures and household isolation across the globe are moving the work of caring for children from the paid economy—schools, day-care centers, and babysitters—to the unpaid economy. So far, 1.27 billion students (72.4 percent) across 177 countries have been affected by school closures (UNESCO). The lack of childcare support is particularly problematic for essential workers, including those in the health sector, who have care responsibilities.

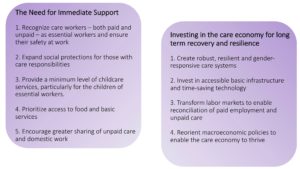

This brief recommends ways to transform care systems now and for the future – both the need for immediate support and the need for sustained investment in the care economy for long term recovery and resilience.

How to Transform Care Systems – Now and for the future

(UN Women, 2020)

Authors/editor(s): Bobo Diallo, Seemin Qayum, and Silke Staab 2020

- Published in COVID 19, Policy Briefs & Reports, UN Women