COVID-19 AND THE CARE ECONOMY: UN Women calls for immediate action and structural transformation for a gender-responsive recovery

A recent brief from UN Women presents emerging evidence on the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic on the care economy.

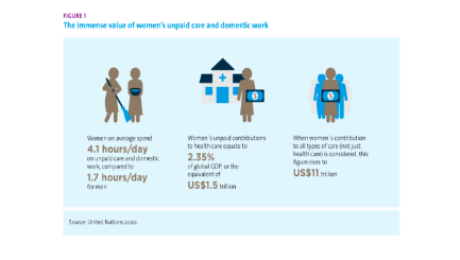

Evidence suggests that the rising demand for care in the context of the COVID-19 crisis and response will likely deepen already existing inequalities in the gender division of labor, placing a disproportionate burden on women and girls. Not only are women over-represented among paid health care workers, girls and women also shoulders the bulk of unpaid care and domestic work that sustains families and communities on a day-to-day basis.

School closures and household isolation across the globe are moving the work of caring for children from the paid economy—schools, day-care centers, and babysitters—to the unpaid economy. So far, 1.27 billion students (72.4 percent) across 177 countries have been affected by school closures (UNESCO). The lack of childcare support is particularly problematic for essential workers, including those in the health sector, who have care responsibilities.

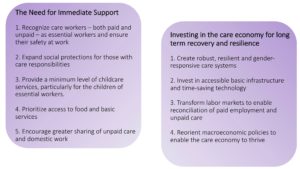

This brief recommends ways to transform care systems now and for the future – both the need for immediate support and the need for sustained investment in the care economy for long term recovery and resilience.

How to Transform Care Systems – Now and for the future

(UN Women, 2020)

Authors/editor(s): Bobo Diallo, Seemin Qayum, and Silke Staab 2020

- Published in COVID 19, Policy Briefs & Reports, UN Women

Inequalities in access to U.S. care services

In the U.S., states and localities are beginning to ease social distancing policies resulting from the pandemic. With many workplaces calling Americans to return to work, the nation’s care services system, what was already broken, is now in dire need of repair or replace.

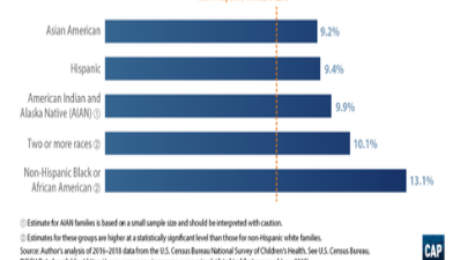

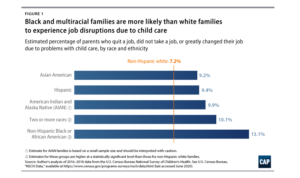

According to a recent analysis by the Center for American Progress (CAP), the lack of adequate child care services in the U.S. negatively affected communities of color before the pandemic, as parents of color were more likely than their non-Hispanic white counterparts to experience child care-related job disruptions that could affect their families’ finances.

The analysis uses the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to show that before the pandemic, Black and multiracial parents experienced child care-related job disruptions—such as quitting a job, not taking a job, or greatly changing their job—due to problems with child care at nearly twice the rate of white parents.

For Black workers and workers of color, decades of occupational and residential segregation has translated to less access to telework, and therefore less flexibility within their responsibilities for young children or elders. In fact, most Black workers and workers of color (especially those who are women) have had to work through the pandemic in essential frontline occupations.

The analysis shows that prior to the pandemic, adequate and affordable child care services was short in supply, particularly for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous families. In fact, more than half of Latinx and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) families have experiences living in a child care desert – which is an area suffering from an inadequate supply of licensed childcare.

Using child care services as an example, the analysis shows that disparities will likely worsen in the aftermath of the pandemic. A previous CAP analysis estimated that nearly 4.5 million child care slots could disappear permanently as a result of COVID-19, effectively cutting an already inadequate child care supply in half. Recent data suggest that this impact is already being felt, with more than 336,000 child care providers—many of whom are immigrants, African American, or Hispanic—losing their jobs between March and April.

Allowing care services to flounder should not be an option; a broken and inadequate care system would slow the nation’s economic recovery and in addition to deepening existing economic and racial inequalities.

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Race Inequality

The Unpaid Care Work and the Labor Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys

How much time do people spend on doing paid and unpaid care work? How do women and men spend their time differently on unpaid care work? Are there any differences in time use among the regions? How do socioeconomic factors influence people’s choices to do paid and unpaid care work?

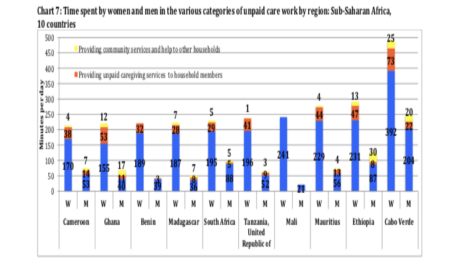

Jacques Charmes addresses these questions in recent ILO report by providing a comprehensive overview of the extent, characteristics and historical trends of unpaid care work. The report is based on the analysis of the most recent time-use surveys carried out at the national level across the world, revealing the differences in time spent on unpaid care work between women and men and among people with different socioeconomic characteristics, such as geographical location, age and income groups, education level, marital status and the presence and age of children in the household. An insightful discussion of the concepts and methodological approaches underlying the analysis of time-use data is also offered.

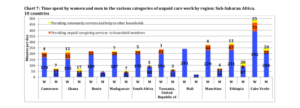

Chart 7 in the ILO Working Paper the Unpaid Care Work and the Labour Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys illustrates the time spent by women and men in various categories of unpaid care work across Sub-Saharan African countries including Cameron, Ghana, Benin, Madagascar, South Africa, Tanzania, Mali, Mauritius, Ethiopia and Cabo Verde. As with the case around the world, women in Sub-Saharan African countries are providing significantly more unpaid care services in households and communities. Read the report to learn more about time-use analysis concepts and methodologies, gender variations in paid and unpaid work across the world and across various socio-economic levels:

International Labour Organization

Gender, Equality and Diversity & ILOAIDS Branch

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy Briefs & Reports

Responsibility Time

If there was ever a time we urgently needed to know more about time use, that time has come. The Covid-19 pandemic utterly changed daily rhythms for many sequestered households and the “opening up” process closed down some old routines.

I’ve done extensive work with time use data, have been in touch with several people/groups trying to measure the impact of the pandemic, and am trying to follow results being reported in other research.

My reactions are conditioned by long-standing concerns about survey methodology.

It is surprisingly hard to get an accurate picture of how people use time, because we all tend to do more than one thing at once. Also, doing is not the whole story—being present, available, on-call, and taking responsibility for others is typically far more time-consuming than specific acts of helping. This is especially true for the care of young children, people who are sick, frail, or suffering a disability.

Sheltering-in-place guidelines, combined with the social distancing, have probably had a much bigger impact on where people are, who they are with, and what they are responsible for—than on their activities.

Yet most surveys focus on activities alone, in several variations. They ask stylized questions about how much time people spent in various activities in a given time period, such as the previous day. Or, they persuade respondents to fill out a time diary in which they report what they did in specific intervals (such as every ten minutes) between waking up in the morning and going to sleep at night.

Note the prominence of the words “activities” and “doing” in both cases. Some surveys reach a bit further. The annual American Time Use Survey (ATUS), for instance, asks people if a child under the age of 13 was “in their care” while they engaged in activities. While the ATUS describes such care as a “secondary activity,” it is better interpreted as a responsibility that strongly influences the way that people organize their activities and plan their schedules.

Being on-call to provide care also creates vulnerability to brief but sometimes incessant interruptions whose impact is probably difficult to measure.

This is important because sheltering in place and sequestration almost certainly increased supervisory demands as much (if not more than) active care of young children. At the same time, social distancing guidelines limited peoples’ ability to provide any supervisory care or assistance to elderly or hospitalized family members.

Furthermore, these constraints are likely to be in place for some time—over the summer, children’s activities outside the home are likely to be restricted. Next fall, school schedules may be modified to reduce social density, by having some students come earlier or later in the day or spend some days at home learning on-line. Who will be on-call to supervise them?

From this perspective, consider some of the fascinating findings from on online survey of U.S. parents in mid-April reported in a recent briefing paper published by the Council on Contemporary Families (CCF). This survey was not based on a random sample (which would be hard to accomplish in a short time frame) and relied on stylized questions regarding time spent in specific activities.

The good news is that surveyed that mothers and fathers agree that fathers began doing more housework and childcare after the onset of the pandemic. This does not surprise me too much, since more men were at home, whether as a result of furlough, unemployment, or ability to telecommute. Like the authors of the paper, I’m hopeful that the experience of spending more time in proximity to kids will increase paternal engagement in the future.

The more striking finding, it seems to me, is that the pandemic did not increase time in domestic labor because some tasks like transporting children, attending children’s events, organizing children’s schedules/activities, and grocery shopping became less frequent.

This implies that time devoted to childcare activities declined even as on-call responsibilitiesincreased.

We need to know more about how parents experienced the intensification of such responsibilities. The CCF report is optimistic that the increased opportunities to perform paid work from home will promote a more egalitarian gender division of labor. I’m not so sure that paid work at home is viable for parents of young children without some delegation of supervisory responsibilities.

The CCF report devotes substantial attention to differences in mothers’ and fathers’ tallies of the way in which domestic responsibilities are allocated, an issue also highlighted by a recent surveys conducted by the New York Times and USA Today. These discrepancies highlight the greatest shortcoming of surveys based on stylized questions—women and men probably interpret questions differently, and reporting of relative participation (as in, who does more than whom) is particularly susceptible to social desirability bias.

Diary-based surveys—even if greatly abbreviated and simplified– would almost certainly yield more accurate results, especially if they included explicit attention to on-call responsibilities. Yet some additional stylized questions—especially about perceptions of supervisory constraints and the experience of doing paid work at home with young children present—would also be super helpful.

* I wish the ATUS also asked how much time sick or frail family members were “in your care” but it does not; nor is it clear how accurate responses to this question regarding children under the age of 13 are.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on May 27th, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Policy Briefs & Reports, Time Use Survey

Policy Brief for Gendering Macroeconomic Analysis and Development: A Theoretical Model for Gender Equitable Development

The CWE-GAM team presents an engendered macroeconomic model as a tool to analyze the role of gender equality and fiscal policy on growth and development.[1]The model incorporates realistic structural features of a market economy –such as excess production capacity and involuntary unemployment– and incorporates an unpaid reproductive sector as well as the physical and social sectors in the public and private market economy. The addition of the unpaid reproductive sector explicitly incorporates the provision of domestic care, establishing a more holistic representation of how the workforce is kept fed, healthy, and able to work. This three-sector model is designed to serve as a tool for policy analysis and gender-responsive budgeting to develop a policy mix targeted toward more gender-equitable development. This brief provides a general overview of the model and example policy analyses.

For complete details of the model and discussion of related literature, please see the full working paper published to the Care Work and the Economy website click here

- Published in Economic Modeling, Gender Inequalities, Policy Briefs & Reports