Climate Change and COVID-19: Why Gender Matters

This article was originally published in the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs on July 9, 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the important intersections of climate change, food security, migration, and socio-economic inequalities. An understanding of the gendered dimensions of these interconnected global concerns is crucial for developing a post-COVID recovery plan that ensures a more equal world and bolsters its resilience.

In many ways, the year 2020 spotlighted the compounding issues societies must reckon with, including climate change, COVID-19, and sustained inequality. Today, we are witnessing the drastic consequences of climate destabilization resulting largely from human actions: frequent heat waves, intense flooding and droughts, water crises, increased biodiversity loss, reduced agricultural productivity, and faster disease transmissions. Many of these underlying causes of climate change also increase the risk of future pandemics. For example, deforestation leading to loss of animal habitat forces animals to migrate and brings them into closer contact with other animals or people, increasing the likelihood of zoonotic transmission.

The effects of climate change are being felt throughout the world; its worst impacts are particularly damaging in poorer regions, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia. Severe and prolonged droughts have already affected the Sahel and most of East Africa. Meanwhile, severe storms and flooding are causing extensive damage across the world, and climate change-related food insecurity has resulted in thousands of deaths. Climate change has also intensified water scarcity, reaching critical levels in seventeen countries. Major rivers no longer reach the ocean, while reservoirs and lakes dry up and underground water aquifers are depleted. As climate change continues, drier areas will only be more prone to drought and humid areas more prone to flooding. As food, water, and other resources become increasingly strained, fierce competition over scarce natural resources is likely to escalate. In fact, natural disasters and climate-related conflicts have already dislocated millions of people. In 2017 alone, the UNHCR estimates about 30.6 million new displacements associated with conflicts across 143 countries and territories.

Making Gender Visible in Climate Change Issues

It is fundamental to note that these aforementioned issues are gendered. Gender disparities in access to resources such as land, credit, and extension training have put many women at greater risk with regards to maintaining their livelihoods and accessing food and water. Climate change not only reflects pre-existing gender inequalities, but it also reinforces them. The pivotal role of women in food security is well-documented. Recent estimates for Africa indicate that women provide 40 percent of labor in crop agriculture while at the same time providing labor in small livestock, poultry, and other food production-related activities. Many are income earners, serving as breadwinners in female-headed households while performing most of the household and family care work. However, gender inequalities in the ownership and control of household assets, gender discrimination in labor markets, and rising work burdens due to male out-migration undermine women’s income generating capabilities. Much of women’s work in food production and food access remain statistically invisible because conventional economic indicators fail to capture the significance of their contributions—contributions that are also overlooked in policymaking.

The gendered consequences of climate change include effects on migration flows. Migration has diversifies livelihoods and serves as an important coping mechanism through the promise of remittances or a better life. Internal and international migrations involve individuals and families seeking protection as refugees from the violence in their communities and states and those whose livelihoods are threatened by natural or man-made factors such as natural disasters, economic crises, or political instability. More recently, the increased frequency of extreme weather events and high temperatures have led to climate-induced migration flows exemplified by the influx of climate refugees seeking entrance into the United States in response to hurricanes, and rural-urban migration in Vietnam in response to typhoons.

The ability of households and their members to relocate varies depending on their resources and their vulnerability to the risk of falling further into poverty. Both the gendered dimension of migration and the climate shock impact on migration decisions are nuanced. Migration can challenge certain social expectations and cultural norms. Household care responsibilities and gender roles may restrain women from migrating. In the case of increased conflicts over natural resources, for instance, women are less able to flee than men as they are often responsible for taking care of the children. In Indonesia, climate shocks have promoted more migration among men. Similarly, male migration in Ethiopia and Nigeria has increased with drought and weather variability, while women are forced to stay put due to financial constraints. On the other hand, increasing demands for care workers in countries with high female labor force participation and aging populations provides employment opportunities for women, fueling international migration flows. In 2019 alone 48 percent of the 272 million (3.5 percent of the world’s population) international immigrants were female.

Gender and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The trends in climate-induced problems have foreshadowed the severity of the crises induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has affected all aspects of everyday life and work and has placed a heavy toll on families, communities, and economies. It threatens food security for tens of millions of people. The COVID-19 crisis, like the climate crisis, is causing disparate impacts across nations and social groups. It poses a much greater risk to elderly persons and those with underlying risk factors. Countries with fewer economic resources and weak social and health infrastructure are at a higher risk, not only in the short term but also in the longer term. Politically underrepresented groups suffer the most from lockdowns, rising unemployment, and unexpected medical costs, exacerbating existing economic inequalities.

More importantly, the COVID-19 crisis also unravels and further amplifies gender inequalities. As millions of people lose their jobs or become forced to work from home, many, especially mothers, are compelled to simultaneously juggle work and childcare responsibilities. Unpaid care work has increased not only with children out of school but also with the heightened care needs of the elderly and the sick, especially when health services are either inaccessible or overwhelmed. Ultimately, many women are earning less, saving less, working precarious or insecure jobs, or living close to poverty.

Gender-based violence is rapidly increasing as well. Many women are being forced to “lock down” at home with their abusers at a time when support services for survivors are being disrupted or made inaccessible. In Peru, the imposition of lockdowns has led to a 48 percent increase in phone calls to the helpline for domestic violence.

The COVID-19 pandemic also exposes the precarious employment conditions of many “essential workers” whose jobs increase their risks of infection and are often employed on temporary contracts. Migrants are among the key workers who deliver essential services; they play a critical role in essential sectors in many high-income countries working as crop pickers, food processors, care assistants, and cleaners in hospitals. These migrant workers help facilitate systemic resilience to threats, but their own vulnerabilities go unaddressed.

Conclusions

We cannot afford to ignore the particular vulnerability of women when analyzing the effects of climate change on food security and migration, and we cannot ignore their susceptibility to food insecurity and violence. As governments and policymakers grapple with the challenge of bolstering resilience, they will need to think beyond the effects of these shocks on markets and to pay more attention to the heightened social and economic inequalities. Such an objective requires a comprehensive, gendered approach that considers women’s roles in the provision of essential goods and services and the differentiated impacts of climate change.

Fiscal stimulus packages and emergency measures have been put in place by many countries to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19, but it is crucial that these responses as well as post-COVID recovery plans put women and girls’ interests and needs, rights, and protection at their center. Such responses and plans should include expanded public investment in the care delivery system, from childcare to healthcare to eldercare, which the COVID-19 crisis has disrupted. There is also a need for gender-sensitive analyses of the effects of economic, social, and migration policies along with the development of legal frameworks that effectively address domestic violence. Meaningful participation of women in policy discourse and dialogue addressing climate change is vital as they are disproportionately vulnerable.

Governments should also undertake and support the collection of sex-disaggregated data on various economic, social, and climate-change related indicators as the lack of data is sometimes used as an excuse not to implement gender-responsive policies. As UN Women has stated, “it is not just about rectifying long-standing inequalities but also about building a more just and resilient world.”

This article was written by the CWE-GAM Project’s Principal Investigator Maria S. Floro and was originally published in the Georgetown Journal for International Affairs on July 9, 2021.

- Published in COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy, Maria Floro, Policy

Women and the Pandemic in the U.S.

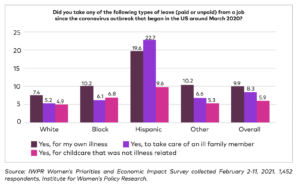

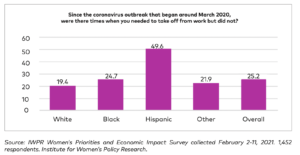

Institute for Women’s Policy Research released a report in February 2021”IWPR Women’s Priorities and Economic Impact Survey” outlining a recent poll of 1452 women in the U.S. The findings are backdropped by the experience of women throughout the pandemic and resulting economic turndown, in which 2.35 million women have left the workforce since February 2020.

Some of the key findings from this survey are:

- 1 in 4 women report that they are worse off financially than one year ago

- Nearly half of all women are worried about the financial situation of their families

- 1 in 4 women report having needed to take time work off but did not do so

- 40% of women reported care demands stopped them from working or forced them to reduce hours

- 69% of women support paid sick time to have a child, recover from a serious health condition, or care for a family member

- 20% of women with children want the Biden administration to address childcare and education in the first 100 days

In terms of women experiencing reduced paid work as a result care demands, this has also been pointed to within recent working papers put out by the

The impact of care demands on women’s paid work is explored in a number of Care Work and the Economy Working Paper Series. For instance in two recent papers, “Gender Wage Equality and Investments in Care: Modeling Equity and Production” and “Parental Caregiving and Household Dynamics”.

Education and childcare were listed among the top priorities for the Biden administration to address within the first 100 days among survey participants. This is largely because women’s ability to reenter the workforce largely depends upon safe reopening of schools and childcare facilities.

Latinas have been hit particularly hard according to this survey, reporting the highest levels of taking leave from jobs in order to provide care. However, across all ethnicities, 69 percent of women expressed strong support for paid sick leave and the ability to take time away from work to provide care or recover from illness.

The Unites States remains the only high-income country in in the world that fails to provide guaranteed paid sick or family leave for workers. The Family Medical Leave Act, which provides unpaid job protection, and only for about 56 percent of workers. The Families First Coronavirus Relief Act has provided access to paid leave as a result of the pandemic but falls short in the fact that more than 100 million workers are excluded from this because they are caregivers.

In order to address the many issues identified throughout this survey, there is strong need for targeted programs and policy solutions that will aid a gender equitable recovery. This recovery should not only address immediate short term needs but include long term strategies that will create more resilient systems that recognize the contributions of women to the workforce, society and family structure.

IWRP specific recommendations for the short term are:

- Continuing economic impact payments

- Expanding access to affordable healthcare

- Providing paid sick and medical leave

- Raising the federal minimum wage

- Building a new childcare infrastructure

Equitable economic recovery necessitates a national care system that meets the needs of all families, raises wages and provides quality childcare, treating it as a public good instead of a private obligation.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Policy, Policy Briefs & Reports, U.S.

Save the Date: Women & Migration Global Mapping Report

On March 1st the Women in Migration Network and Friedrich-Ebert- Stiftung is launching a new report mapping organizations working on gender and migration around the world “No Borders to Equality.”

This new report has mapped over 300 organizations around the world working at the intersection of gender and migration. It is based on a survey and interviews that identify key priorities, concerns, advocacy and mobilization, and which reveal the tremendous potential and importance of bringing a gender perspective to the dynamic issues of migration today.

In addition to the report (which will be available in English and with an Executive Summary in English, Spanish and French), an interactive website is being developed to help in identifying and locating these key groups in the various global regions.

To accommodate global time zones, the launch event will take place at two different times. You can register for either event:

(Asia Focus) 5pm PHST/10am CET

Register at: http://bit.ly/WIMNFESwebinar1

(Global Focus) 10am EST/4pm CET

Register at: http://bit.ly/WIMNFESwebinar2

– traducción al español

– interprétation en français

Be sure to attend this exciting event to learn more.

- Published in Events, Gender Inequalities, Policy Briefs & Reports

Spirals of Inequality: A Women’s Budget Group Special Report

The Women’s Budget Group Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy, launched in February 2019, is an expert-led project aimed at developing economic policies that promote gender equality across the United Kingdom. The Commission utilizes a number of avenues and tools to achieve this objective, one of which is the recent release of the report “Spirals of Inequality: How Unpaid Care is at the Heart of Gender Inequalities.”

This first report released by the Commission seeks to trace the problem of how gender inequalities in the UK are produced and maintained by observing the problem through the following perspectives:

Unpaid Work: Women Continue to do the Lion’s Share

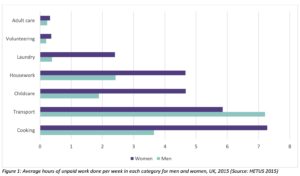

The unequal division of labor within unpaid care work is at the heart of gender inequality in the UK, with women taking on 60% of the unpaid work on average. This includes care work, cooking, and cleaning among other tasks.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

Limiting Opportunities for Paid Work: Women More Likely to Work Part-Time and Earn Less

This phenomenon puts a disproportionate strain on women and contributes to gender inequality. Mothers with young children are 3-4 times more likely to work part-time, and women, in general, are far more likely to be in precarious forms of employment such as temporary work. This is especially true for women of color. The part-time work conundrum is driving the gender gap, and on average women earn 43% less than men. Furthermore, a pay gap of 8.9% persists, further exacerbating this issue. Again, this being more predominate with women of color.

Despite women becoming increasingly educated, they persist in being overrepresented in low-wage sectors of the economy such as health and social work. Feminist economists have argued that a reason behind this is such sectors are viewed as an extension of a women’s “natural” work.

These issues create a perpetual cycle that allows for the inequality between men and women to continue.

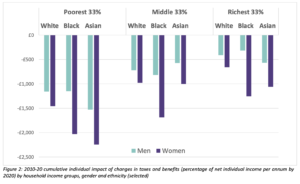

Life Course Implications: Benefits Make Up a Larger Portion of Income and Austerity Hits Harder

Among single households living in poverty, those led by women make up for 86%. Furthermore, pensioners living alone are far more likely to be at the poverty level if that individual is a woman. Since tax reforms began in 2010 throughout the UK, women have also been hit hardest. These benefits make up a large portion of women’s incomes and cuts to these benefits and tax giveaways benefit those fitting into a higher wealth bracket.

Public Services: Women Hit Hardest by Cutbacks

Cuts to public spending throughout the UK have also hit women disproportionately hard, as women are most likely to utilize public services. The poorest families and especially those in poverty-level households led by women have taken a particularly bad hit; many single mothers have had to cut living standards by up to 10% as a result of a cut to public services between 2010 and 2017.

Furthermore, these cuts have put a greater burden on family members to provide care for the elderly members of their family, much of this falling onto female members. This often comes at the expense of their own employment.

Violence Against Women: “Cause and Consequence” of Women’s Economic Equality

All of the factors that lead to the economic disparity between men and women also make it increasingly difficult for women to leave abusive partners. Furthermore, poorer households have higher rates of domestic abuse, and this perpetuating poverty limits women’s options while increasing their vulnerability.

Moving Forward: Next Steps for the Commission

The WBG Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy is striving to develop an alternative economic approach aimed at addressing these issues. Through this initiative, they aim to build an economy that is desirable, economically feasible, and necessary for fairness, sustainability, and resilience. To learn more about the Commission and its work, sign up to attend the upcoming webinar “Creating a Caring Economy: A Call to Action” on September 30, 2020.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy

Reflections on Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Growth

Despite notable progress in recent decades (including in primary school enrolment and access to the political system), gender gaps remain pervasive in rich and poor countries alike. In many developing economies, gaps in secondary and tertiary education, access to finance and health care, labor force participation, formal sector employment, entrepreneurship and earnings, remain large. In today’s low- and middle-income countries for instance, the labor force participation rate for women is only 57 percent, compared to 85 percent for men. Women’s share in the formal sector employment remains low and in recent years has even fallen in some cases. On average, women workers earn about three-quarters of what men earn. In Sub-Saharan Africa more specifically, women still have fewer years of education and fewer skills than men; and learning gaps remain large. Wage and employment gaps in certain occupations (particularly in managerial positions) and activities, and gaps in access to justice and political representation, also remain sizable.

In recent years formal academic research has shed new light on the causes of gender gaps and their consequences for economic growth. The mainstream analytical literature has identified several channels through which gender inequality may affect growth. One of them is the infrastructure-time allocation channel, which emphasizes the fact that, in addition to the conventional positive effects on factor productivity and private investment, improved access to infrastructure reduces the time that women allocate to household chores, and this may, in turn, allow them to devote more time to remunerated labor market activities. In addition, infrastructure may also have a significant impact on health and education outcomes, for both men and women, which may in turn affect their productivity, relative earnings, and indirectly the allocation of time within the family.

CWE-GAM working paper Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Growth further explores how improved access to infrastructure affects women’s time allocation decisions and how, in turn, changes in these decisions affect the process of economic growth in low-income developing countries. To do so it develops a simple two-period, gender-based overlapping generations model with public capital to explore the implications of public infrastructure on women’s time allocation and growth. The focus is on the specific impact of access to public infrastructure services (whose supply can be directly influenced by policy decisions) on female time allocation decisions between market work and home production, and its interactions with economic growth. As in some existing contributions, the basic model accounts not only for the standard productivity effect of public infrastructure but also for its effect on home production and occupational choices. In addition, the case where gender bias and bargaining power, as well as fertility choices and rearing time, are endogenous, and the case where there are two types of infrastructure, physical infrastructure (which includes transport, water supply, and sanitation, telecommunications, and energy) and social infrastructure (which includes the provision of maternal care), are also considered.

The analysis shows that by inducing women to reallocate time away from home production activities and toward market work, improved government provision of infrastructure services—assuming a sufficient degree of efficiency—may help to trigger a process through which a poor country may escape from a low-growth trap. This result is in line with those established in a number of recent contributions. It is also shown that with endogenous gender bias and bargaining power, there are two additional channels through which improved access to infrastructure can affect growth: positive effects on the level and rate of savings, which tends to promote growth. However, the increase in both the public and capital stocks implies that the net effect on the public-private capital ratio, and thus women’s time allocation, is ambiguous in general. This is due to the fact that higher private capital stock increases congestion costs, which tend to lower the public-private capital ratio. By implication, the net effect on gender equality in the market place, and economic growth, is now also ambiguous. Thus, improved access to infrastructure may not always be beneficial.

With endogenous fertility and child-rearing, improved access to infrastructure may raise the fertility rate and total rearing time, thereby mitigating the positive effect on women’s time allocated to market work. However, this effect is not robust. In addition, if there is a positive externality associated with improved access to infrastructure, this may lead not only to a reduction in time allocated to household chores but also to a reduction in total time allocated to child-rearing. In turn, this may lead to women allocating more time to market work, thereby promoting growth. Finally, the analysis highlights the fact that although the physical and social infrastructure is complementary at the microeconomic level, a trade-off exists at the macroeconomic level as a result of the government’s budget constraint. The optimal policy that internalizes this trade-off must account for the relative efficiency of investment in these two types of assets.

This blog is authored by Pierre-Richard Agénor and Madina Agénor who are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Gender Inequalities, Rethinking Macroeconomics

Reflections on Microfinance and the Care Economy

With rollback of the developmental state under the neoliberal policy regime, financial inclusion has come to be adopted as a developmental strategy. Micro-credit schemes, which were initially promoted as tools for gender-empowerment and poverty alleviation, have in the process become increasingly absorbed within the sphere of mainstream private finance. The relatively low rates of default in this sector have attracted an influx of funds from profit oriented financial institutions. The focus has shifted from the sustainability of income generation for borrowers to that of the profitability of the lending institution. Given the higher transaction costs associated with small loans and extending outreach to marginal low income households this change of focus has undermined the social mission of microfinance to reach the poorest and most neglected households. Social priorities are being subordinated to commercial considerations.

The impact of micro-credit on both poverty and gender relations has been extensively studied. However, the implications of the growth of micro-credit for the care-economy, and their repercussions in the wider macro-economy have received less analytical attention. The neglect of the implication microfinance for the provision of care labor is surprising in the light of the original mission of microfinance, which targeted the female worker in rural areas in developing countries, with less access to earning opportunities and disproportionate responsibility for the care work. The increase in market labor implies a claim on the time of working women. In the absence of social provisioning of care, this claim on the labor time of women could lead to a squeeze on the time of rural working women

A simple two-sector post-Keynesian model allows the integration of the role of demand and care work into the analysis of microfinance. This investigation demonstrates is that micro financed enterprises face a structural constraint on the demand side from overall macroeconomic conditions, and on the supply side from the responsibility for unpaid care work borne by the female beneficiary of microfinance. Paradoxically, microfinance has been espoused as a developmental strategy in precisely the period when the role of the developmental state has been eclipsed, and cutbacks in public spending on care provisioning have been prescribed.

Slowdowns in the wider economy, would lower the demand for the output of the microfinance sector, and hence undermine the viability of these enterprises. The capacity of the microfinance sector to provide the impetus to broader demand growth in the economy is likely to be more limited in the absence of public policies to stimulate demand and investment. The capacity of microfinance to alleviate poverty and lift incomes is thus dependent on conditions in, and linkages with the wider macroeconomy. A vibrant and stable macroeconomy is the only sustainable basis for a stable microfinance sector.

We also draw attention to some of the complexities of the impact of microfinance on the provision of care. The home-based nature of microenterprises perpetuates the gendered asymmetries of care responsibility within the household. While higher female earnings can alleviate the burden of care by making care work more effective and by enabling the market to substitute for unpaid care, at the lower income levels and in a context of the inadequate social provision of care the gendered responsibility for care remains a critical constraint for the female beneficiary of micro-finance.

Some clear policy prescriptions emerge from this investigation. Donors and development agencies have been encouraging raising interest rates in order to ensure the viability and profitability of microfinance lenders. Our model suggests that high-interest rates will actually undermine the scope of microfinance as a path to better and sustainable livelihoods for poor households in rural areas. Higher interest rates in this sector impose a higher burden on the labor time of the female worker with a consequent squeeze of care-labor or the own labor time.

More significantly, the analysis suggests that microfinance cannot be an effective path to poverty alleviation or gender empowerment unless it is backed by investment in the social provisioning of care. The success of microfinance as a developmental strategy depends on wider policies that support demand and the social provision of care. There is, in the final analysis, no substitute for a developmental strategy based on public investment in support of both job creation and social provision of care.

This blog was authored by Ramaa Vasudevan and Srinivas Raghavendran are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in Economic Modeling, Gender Inequalities, Rethinking Macroeconomics

Inequalities in access to U.S. care services

In the U.S., states and localities are beginning to ease social distancing policies resulting from the pandemic. With many workplaces calling Americans to return to work, the nation’s care services system, what was already broken, is now in dire need of repair or replace.

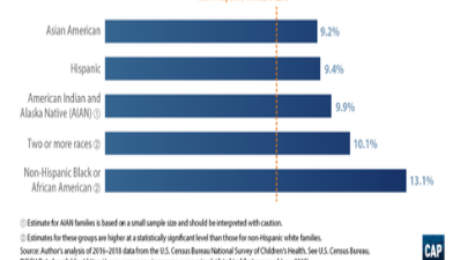

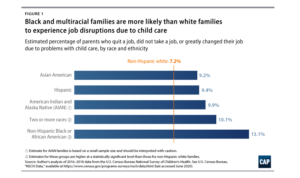

According to a recent analysis by the Center for American Progress (CAP), the lack of adequate child care services in the U.S. negatively affected communities of color before the pandemic, as parents of color were more likely than their non-Hispanic white counterparts to experience child care-related job disruptions that could affect their families’ finances.

The analysis uses the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to show that before the pandemic, Black and multiracial parents experienced child care-related job disruptions—such as quitting a job, not taking a job, or greatly changing their job—due to problems with child care at nearly twice the rate of white parents.

For Black workers and workers of color, decades of occupational and residential segregation has translated to less access to telework, and therefore less flexibility within their responsibilities for young children or elders. In fact, most Black workers and workers of color (especially those who are women) have had to work through the pandemic in essential frontline occupations.

The analysis shows that prior to the pandemic, adequate and affordable child care services was short in supply, particularly for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous families. In fact, more than half of Latinx and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) families have experiences living in a child care desert – which is an area suffering from an inadequate supply of licensed childcare.

Using child care services as an example, the analysis shows that disparities will likely worsen in the aftermath of the pandemic. A previous CAP analysis estimated that nearly 4.5 million child care slots could disappear permanently as a result of COVID-19, effectively cutting an already inadequate child care supply in half. Recent data suggest that this impact is already being felt, with more than 336,000 child care providers—many of whom are immigrants, African American, or Hispanic—losing their jobs between March and April.

Allowing care services to flounder should not be an option; a broken and inadequate care system would slow the nation’s economic recovery and in addition to deepening existing economic and racial inequalities.

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Race Inequality

UN Women: COVID-19 and the Crisis of the Care Economy

In a recent UN Women blog post, Silke Staab explores ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic that has swept the globe is further compounding the risk and strain put upon women in the care economy – both paid and unpaid.

Women comprise 70% of health workers globally and even higher shares of care-related occupations such as nursing, midwifery and community health work, which all require close contact with patients. The risks these front-line workers take to save lives are compounded by poor working conditions, low pay and lack of voice in health systems where medical leadership is largely controlled by men.

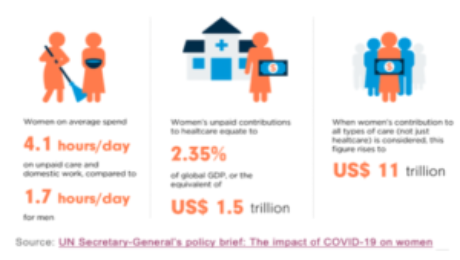

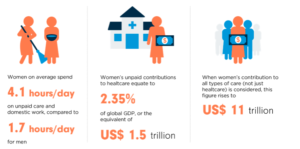

It is estimated that unpaid health care, in which the burden primarily fall onto women, is equivalent to a staggering $1.5 trillion globally. When factoring in all other types of care work, that figure climbs to $11 trillion. Furthermore, community health workers that receive no compensation, again mostly comprised of women, are vital to the health and wellbeing of communities all over the world. These care workers are in desperate need of proper equipment, training and financial support in the face of this current pandemic.

Source: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women

The increased burden of childcare due to school closures and social distancing is also bound to negatively affect the well-being of the women taking on these tasks. This is further exacerbated by the loss of assistance from elders in the family, who must keep themselves protected from COVID-19 due to being in a vulnerable category.

On the flip side of that is the reliance of elderly people on the informal care of their family members, but this reliance puts them at greater risk of being exposed. Providing these family care workers with the proper assistance and protective gear in order to continue their duties while minimizing the risk to their loved ones is an essential first step in facing this particular challenge.

Although this pandemic has caused an immense strain on the care economy, the situation has created an opportunity to reevaluate priorities and reassess the economic value of these essential services being provided through care work. A people-centered plan for economic recovery should take this into account and prioritize long-overdue investments in the care economy.

Silke Staab is a research specialist at UN Women.

This blog was originally posted on the UN Women website on April 22, 2020. Read this blog post here.

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities, UN Women

A Gender Lens on COVID-19: Investing in Nurses and Other Frontline Health Workers to Improve Health Systems

In a recent CGD blog post, author Megan O’Donnell highlighted seven areas where long-run, gender-responsive thinking can help to insulate against the consequences of pandemics like COVID-19 and their disproportionate impacts on women and girls. Here we take a deeper dive into one of those areas: the promotion of a gender-equal global health workforce in which the occupations where women predominate, such as nursing and community health work, are valued, prioritized, and properly resourced.

Worldwide, women make up anywhere from 65 percent (Africa) to 86 percent (Americas) of the nursing workforce. Their jobs are critical to the health, safety, and security of communities on any given day, and particularly in times of a global pandemic. And yet, more obviously now than ever before, we face a global nursing shortage. To address this critical short fall and ensure sufficient numbers and distribution of health workers to provide both emergency and routine care in time of crisis, governments need to increase and improve their long-term investment in nurses, including by addressing gender gaps in the health workforce.

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities, Healthcare

Those unprotected by the “economic stability shield”

This brief note raises two issues: First, the widening of gender inequalities in unpaid care work and second, the potential gendered outcomes of rising formal and informal unemployment in the affected sectors in Turkey.

Market production is at a halt, yet women are working overtime

What sustains human life, as we all know, cannot be maintained solely by market purchased goods and services. Our lives are constantly reproduced within households. The overwhelming majority of women are involved in the provisioning of the most indispensable items needed to sustain our lives and enhance their quality.

We are told that economies are experiencing a “sudden stop”. While some businesses temporarily close their doors, there is full capacity production ongoing at our homes. In technical terms, excess capacity in market production is rising, while women are working overtime. Some forms of housework now require more attention and diligence for hygienic purposes than ordinary times. Sterilizing market purchased goods, washing the clothes and cleaning the house more frequently are now necessary. The shutdown of nurseries, kindergartens and schools increased childcare work burden. Adult and elderly care burden also increased. Turkey has banned people aged 65 or older from leaving their homes on March 21 and people aged 20 or younger very recently. These developments significantly increase women’s workload. The family has already been central to the welfare regime of Turkey. Care of children, elderly and people with disabilities have been overly dependent on families. We observe once again, the family-centered welfare regime shifts the care burden onto the families.

The unemployed and informal workers

As of December 2019, prior to the pandemic, nearly 4.3 million people were unemployed. It is assumed that approximately 9-10 million people will be unemployed after the pandemic. The unemployed and their household members–nearly half the population in Turkey—are at serious poverty risk.

“Economic Stability Shield” Package consists mostly of policies that aim to help the firm owners and ignores the most vulnerable segments: the long-term unemployed, first-time job seekers and the recently employed.

The other segment of the population overlooked by the Package is the unregistered or informal workers. More than five million workers, are working informally, and hence without social security, in Turkey.

It is clear that small and medium-sized companies, where informal work is widespread will be more adversely affected by the crisis. Accommodation and food (tourism sector at large), retail trade, and textiles and apparel will be most affected due to the pandemic. We estimate that 650 thousand informal workers in these three sectors are in danger of losing their jobs. In addition, over 700 thousand informal workers from the remaining sectors are estimated to lose their jobs.

The three sectors that are most affected by job losses make up almost a quarter of non-agricultural women’s employment. Even if we assume that there would be no employer discrimination and employers act in accordance with these current rates during layoffs, around 700 thousand women will lose their jobs, and around 190 thousand of those will not have any access to social security benefits since they have been working informally.

Our lives are upside down now and the future does not look bright at all. However, it is not the time to be pessimistic either. As we all know, all inequalities are socially constructed; their elimination will be too. If our struggle to rearrange our lives during and after this epidemic; will be towards more solidarity and towards an egalitarian society, we can start by deciphering all kinds of inequality, discrimination and exploitation inside and outside our homes.

This blog was authored by Emel Memiş, Department of Economics, Ankara University, KEFA and IAFFE member; Murat Koyuncu, Department of Economics, Boğaziçi University and Şemsa Özar, Department of Economics, Boğaziçi University, KEFA member, member and former president of IAFFE

- Published in Gender Inequalities, Turkey, Unpaid Work

- 1

- 2