Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part II

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” The discussion describes the interconnections between the crisis of care, the deepening ecological crisis and growth and accumulation processes.

There are many common threads with the climate and ecological crisis and the care crisis. Significantly, the idea that economic growth is overall beneficial. The type of economic growth generally pursued worldwide has not only increased stresses put upon the earth’s resource base but also on care labor capacity, which is similarly but wrongly perceived to be of infinite supply. Moreover, arguments that equate economic growth with overall improvement fail to recognize the distributional element of rising income inequality, which is far more nuanced. In fact, among countries that are higher income, gains from economic growth within those nations do not trickle down to everyone. When looking at care, the widening income equality gaps has shifted distribution of care givers across social classes and national boundaries. As a result, the quality and adequacy of care within a single nation can be very different, which exacerbates differences in social reproduction.

At the same time, income inequality has created a solution for the care needs of those that have the means to hire care for children and elderly, because care workers in those sectors are often paid low wages. But for the working poor, hiring care work help is inaccessible due to financial constraints, therefore they rely on their kinship networks to help provide this care. Furthermore, much of the care work burden still falls on women even as they enter to labor force. Economics and social policy in many parts of the world continue to neglect the heavy work burden put upon women and the necessity to balance household care activities and market work. What can also be observed is a global care supply chain, with the migration of women and girls to urban areas to provide care for wealthier families. Care itself is becoming one of the drivers of income inequality.

The economy is not all about material production; it is really about human vision and social provisions. However, an illusion has been created that unpaid care work is a natural resource that serves as an input for market production to promote GDP growth. However, this idea does not take into account that the wellbeing of people, especially the elderly, the sick and children should be an end in and of itself, to achieve sustainable growth. There is much work to be done to address these issues. To begin, economists must envision long term horizons that look forward to future generations while also taking into account the interdependence of life and moral responsibility. They must also integrate care and environmental consequences into our economic policy tools. Overall a new economic paradigm that includes green ecology and feminist economic concerns is needed.

Link to Part 1 of this blog here.

- Published in COVID 19, Economic Modeling, Elder Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, Field Work, Gender-Aware Macromodels, South Korea

Spirals of Inequality: A Women’s Budget Group Special Report

The Women’s Budget Group Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy, launched in February 2019, is an expert-led project aimed at developing economic policies that promote gender equality across the United Kingdom. The Commission utilizes a number of avenues and tools to achieve this objective, one of which is the recent release of the report “Spirals of Inequality: How Unpaid Care is at the Heart of Gender Inequalities.”

This first report released by the Commission seeks to trace the problem of how gender inequalities in the UK are produced and maintained by observing the problem through the following perspectives:

Unpaid Work: Women Continue to do the Lion’s Share

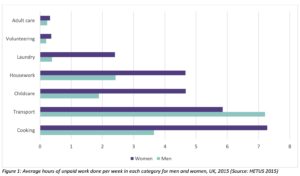

The unequal division of labor within unpaid care work is at the heart of gender inequality in the UK, with women taking on 60% of the unpaid work on average. This includes care work, cooking, and cleaning among other tasks.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

Limiting Opportunities for Paid Work: Women More Likely to Work Part-Time and Earn Less

This phenomenon puts a disproportionate strain on women and contributes to gender inequality. Mothers with young children are 3-4 times more likely to work part-time, and women, in general, are far more likely to be in precarious forms of employment such as temporary work. This is especially true for women of color. The part-time work conundrum is driving the gender gap, and on average women earn 43% less than men. Furthermore, a pay gap of 8.9% persists, further exacerbating this issue. Again, this being more predominate with women of color.

Despite women becoming increasingly educated, they persist in being overrepresented in low-wage sectors of the economy such as health and social work. Feminist economists have argued that a reason behind this is such sectors are viewed as an extension of a women’s “natural” work.

These issues create a perpetual cycle that allows for the inequality between men and women to continue.

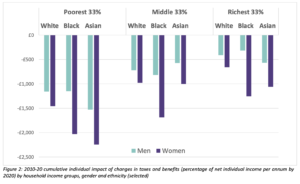

Life Course Implications: Benefits Make Up a Larger Portion of Income and Austerity Hits Harder

Among single households living in poverty, those led by women make up for 86%. Furthermore, pensioners living alone are far more likely to be at the poverty level if that individual is a woman. Since tax reforms began in 2010 throughout the UK, women have also been hit hardest. These benefits make up a large portion of women’s incomes and cuts to these benefits and tax giveaways benefit those fitting into a higher wealth bracket.

Public Services: Women Hit Hardest by Cutbacks

Cuts to public spending throughout the UK have also hit women disproportionately hard, as women are most likely to utilize public services. The poorest families and especially those in poverty-level households led by women have taken a particularly bad hit; many single mothers have had to cut living standards by up to 10% as a result of a cut to public services between 2010 and 2017.

Furthermore, these cuts have put a greater burden on family members to provide care for the elderly members of their family, much of this falling onto female members. This often comes at the expense of their own employment.

Violence Against Women: “Cause and Consequence” of Women’s Economic Equality

All of the factors that lead to the economic disparity between men and women also make it increasingly difficult for women to leave abusive partners. Furthermore, poorer households have higher rates of domestic abuse, and this perpetuating poverty limits women’s options while increasing their vulnerability.

Moving Forward: Next Steps for the Commission

The WBG Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy is striving to develop an alternative economic approach aimed at addressing these issues. Through this initiative, they aim to build an economy that is desirable, economically feasible, and necessary for fairness, sustainability, and resilience. To learn more about the Commission and its work, sign up to attend the upcoming webinar “Creating a Caring Economy: A Call to Action” on September 30, 2020.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy

Reflections on Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Growth

Despite notable progress in recent decades (including in primary school enrolment and access to the political system), gender gaps remain pervasive in rich and poor countries alike. In many developing economies, gaps in secondary and tertiary education, access to finance and health care, labor force participation, formal sector employment, entrepreneurship and earnings, remain large. In today’s low- and middle-income countries for instance, the labor force participation rate for women is only 57 percent, compared to 85 percent for men. Women’s share in the formal sector employment remains low and in recent years has even fallen in some cases. On average, women workers earn about three-quarters of what men earn. In Sub-Saharan Africa more specifically, women still have fewer years of education and fewer skills than men; and learning gaps remain large. Wage and employment gaps in certain occupations (particularly in managerial positions) and activities, and gaps in access to justice and political representation, also remain sizable.

In recent years formal academic research has shed new light on the causes of gender gaps and their consequences for economic growth. The mainstream analytical literature has identified several channels through which gender inequality may affect growth. One of them is the infrastructure-time allocation channel, which emphasizes the fact that, in addition to the conventional positive effects on factor productivity and private investment, improved access to infrastructure reduces the time that women allocate to household chores, and this may, in turn, allow them to devote more time to remunerated labor market activities. In addition, infrastructure may also have a significant impact on health and education outcomes, for both men and women, which may in turn affect their productivity, relative earnings, and indirectly the allocation of time within the family.

CWE-GAM working paper Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Growth further explores how improved access to infrastructure affects women’s time allocation decisions and how, in turn, changes in these decisions affect the process of economic growth in low-income developing countries. To do so it develops a simple two-period, gender-based overlapping generations model with public capital to explore the implications of public infrastructure on women’s time allocation and growth. The focus is on the specific impact of access to public infrastructure services (whose supply can be directly influenced by policy decisions) on female time allocation decisions between market work and home production, and its interactions with economic growth. As in some existing contributions, the basic model accounts not only for the standard productivity effect of public infrastructure but also for its effect on home production and occupational choices. In addition, the case where gender bias and bargaining power, as well as fertility choices and rearing time, are endogenous, and the case where there are two types of infrastructure, physical infrastructure (which includes transport, water supply, and sanitation, telecommunications, and energy) and social infrastructure (which includes the provision of maternal care), are also considered.

The analysis shows that by inducing women to reallocate time away from home production activities and toward market work, improved government provision of infrastructure services—assuming a sufficient degree of efficiency—may help to trigger a process through which a poor country may escape from a low-growth trap. This result is in line with those established in a number of recent contributions. It is also shown that with endogenous gender bias and bargaining power, there are two additional channels through which improved access to infrastructure can affect growth: positive effects on the level and rate of savings, which tends to promote growth. However, the increase in both the public and capital stocks implies that the net effect on the public-private capital ratio, and thus women’s time allocation, is ambiguous in general. This is due to the fact that higher private capital stock increases congestion costs, which tend to lower the public-private capital ratio. By implication, the net effect on gender equality in the market place, and economic growth, is now also ambiguous. Thus, improved access to infrastructure may not always be beneficial.

With endogenous fertility and child-rearing, improved access to infrastructure may raise the fertility rate and total rearing time, thereby mitigating the positive effect on women’s time allocated to market work. However, this effect is not robust. In addition, if there is a positive externality associated with improved access to infrastructure, this may lead not only to a reduction in time allocated to household chores but also to a reduction in total time allocated to child-rearing. In turn, this may lead to women allocating more time to market work, thereby promoting growth. Finally, the analysis highlights the fact that although the physical and social infrastructure is complementary at the microeconomic level, a trade-off exists at the macroeconomic level as a result of the government’s budget constraint. The optimal policy that internalizes this trade-off must account for the relative efficiency of investment in these two types of assets.

This blog is authored by Pierre-Richard Agénor and Madina Agénor who are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Gender Inequalities, Rethinking Macroeconomics

COVID-19 AND THE CARE ECONOMY: UN Women calls for immediate action and structural transformation for a gender-responsive recovery

A recent brief from UN Women presents emerging evidence on the impact of the COVID-19 global pandemic on the care economy.

Evidence suggests that the rising demand for care in the context of the COVID-19 crisis and response will likely deepen already existing inequalities in the gender division of labor, placing a disproportionate burden on women and girls. Not only are women over-represented among paid health care workers, girls and women also shoulders the bulk of unpaid care and domestic work that sustains families and communities on a day-to-day basis.

School closures and household isolation across the globe are moving the work of caring for children from the paid economy—schools, day-care centers, and babysitters—to the unpaid economy. So far, 1.27 billion students (72.4 percent) across 177 countries have been affected by school closures (UNESCO). The lack of childcare support is particularly problematic for essential workers, including those in the health sector, who have care responsibilities.

This brief recommends ways to transform care systems now and for the future – both the need for immediate support and the need for sustained investment in the care economy for long term recovery and resilience.

How to Transform Care Systems – Now and for the future

(UN Women, 2020)

Authors/editor(s): Bobo Diallo, Seemin Qayum, and Silke Staab 2020

- Published in COVID 19, Policy Briefs & Reports, UN Women

The Unpaid Care Work and the Labor Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys

How much time do people spend on doing paid and unpaid care work? How do women and men spend their time differently on unpaid care work? Are there any differences in time use among the regions? How do socioeconomic factors influence people’s choices to do paid and unpaid care work?

Jacques Charmes addresses these questions in recent ILO report by providing a comprehensive overview of the extent, characteristics and historical trends of unpaid care work. The report is based on the analysis of the most recent time-use surveys carried out at the national level across the world, revealing the differences in time spent on unpaid care work between women and men and among people with different socioeconomic characteristics, such as geographical location, age and income groups, education level, marital status and the presence and age of children in the household. An insightful discussion of the concepts and methodological approaches underlying the analysis of time-use data is also offered.

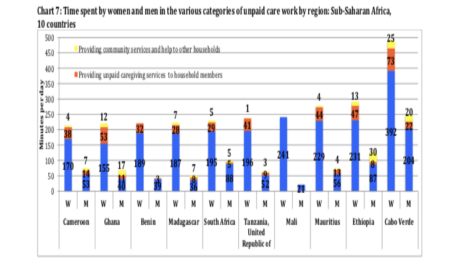

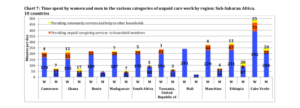

Chart 7 in the ILO Working Paper the Unpaid Care Work and the Labour Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys illustrates the time spent by women and men in various categories of unpaid care work across Sub-Saharan African countries including Cameron, Ghana, Benin, Madagascar, South Africa, Tanzania, Mali, Mauritius, Ethiopia and Cabo Verde. As with the case around the world, women in Sub-Saharan African countries are providing significantly more unpaid care services in households and communities. Read the report to learn more about time-use analysis concepts and methodologies, gender variations in paid and unpaid work across the world and across various socio-economic levels:

International Labour Organization

Gender, Equality and Diversity & ILOAIDS Branch

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy Briefs & Reports

UN Women: COVID-19 and the Crisis of the Care Economy

In a recent UN Women blog post, Silke Staab explores ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic that has swept the globe is further compounding the risk and strain put upon women in the care economy – both paid and unpaid.

Women comprise 70% of health workers globally and even higher shares of care-related occupations such as nursing, midwifery and community health work, which all require close contact with patients. The risks these front-line workers take to save lives are compounded by poor working conditions, low pay and lack of voice in health systems where medical leadership is largely controlled by men.

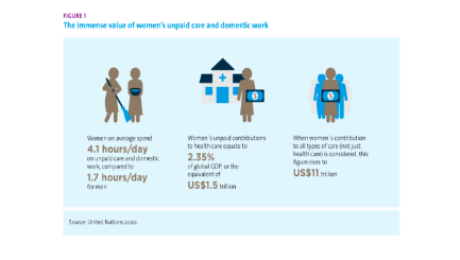

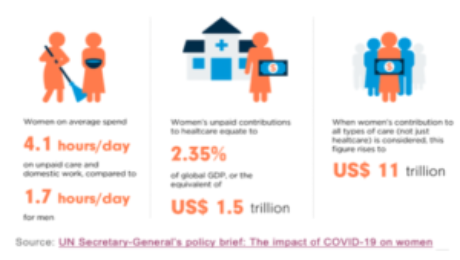

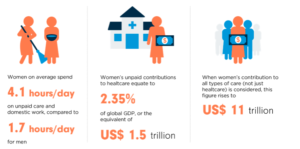

It is estimated that unpaid health care, in which the burden primarily fall onto women, is equivalent to a staggering $1.5 trillion globally. When factoring in all other types of care work, that figure climbs to $11 trillion. Furthermore, community health workers that receive no compensation, again mostly comprised of women, are vital to the health and wellbeing of communities all over the world. These care workers are in desperate need of proper equipment, training and financial support in the face of this current pandemic.

Source: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women

The increased burden of childcare due to school closures and social distancing is also bound to negatively affect the well-being of the women taking on these tasks. This is further exacerbated by the loss of assistance from elders in the family, who must keep themselves protected from COVID-19 due to being in a vulnerable category.

On the flip side of that is the reliance of elderly people on the informal care of their family members, but this reliance puts them at greater risk of being exposed. Providing these family care workers with the proper assistance and protective gear in order to continue their duties while minimizing the risk to their loved ones is an essential first step in facing this particular challenge.

Although this pandemic has caused an immense strain on the care economy, the situation has created an opportunity to reevaluate priorities and reassess the economic value of these essential services being provided through care work. A people-centered plan for economic recovery should take this into account and prioritize long-overdue investments in the care economy.

Silke Staab is a research specialist at UN Women.

This blog was originally posted on the UN Women website on April 22, 2020. Read this blog post here.

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities, UN Women

A Gender Lens on COVID-19: Investing in Nurses and Other Frontline Health Workers to Improve Health Systems

In a recent CGD blog post, author Megan O’Donnell highlighted seven areas where long-run, gender-responsive thinking can help to insulate against the consequences of pandemics like COVID-19 and their disproportionate impacts on women and girls. Here we take a deeper dive into one of those areas: the promotion of a gender-equal global health workforce in which the occupations where women predominate, such as nursing and community health work, are valued, prioritized, and properly resourced.

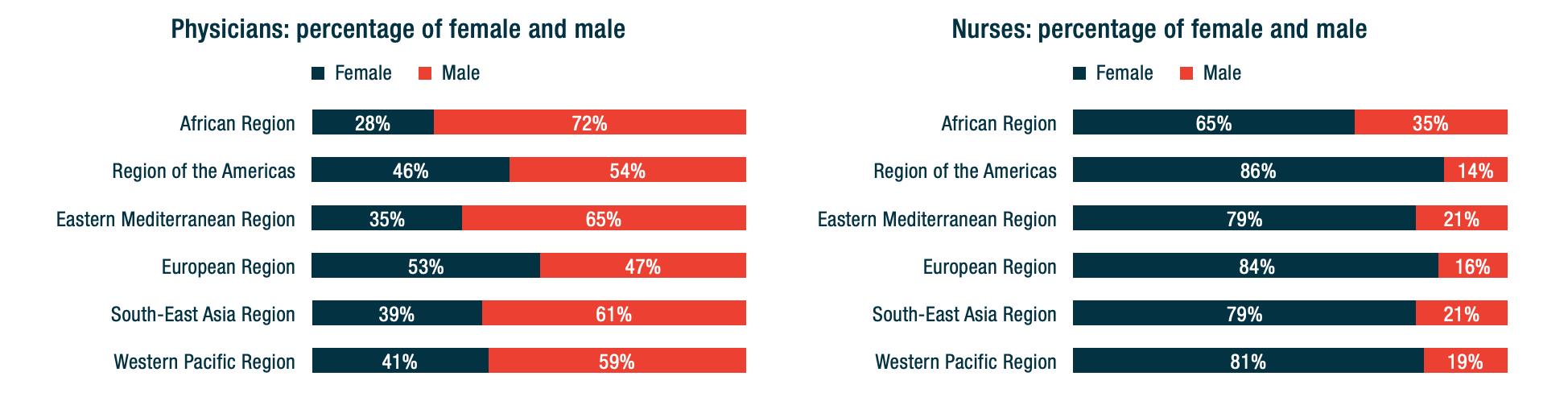

Worldwide, women make up anywhere from 65 percent (Africa) to 86 percent (Americas) of the nursing workforce. Their jobs are critical to the health, safety, and security of communities on any given day, and particularly in times of a global pandemic. And yet, more obviously now than ever before, we face a global nursing shortage. To address this critical short fall and ensure sufficient numbers and distribution of health workers to provide both emergency and routine care in time of crisis, governments need to increase and improve their long-term investment in nurses, including by addressing gender gaps in the health workforce.

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities, Healthcare

How Will COVID-19 Affect Women and Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries?

Policymakers should be thinking—and worried—about how COVID-19 is expected to disproportionately affect women and girls. Gender inequality can come into even starker focus in the context of health emergencies. With COVID-19 continuing to spread, what do we see so far—and what can we expect in the future—in terms of the impacts on women and girls?

Wenham, Smith, and Morgan discuss gendered impacts in their article, “COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak,” in the Lancet. Women appear to be less likely to die from COVID-19: “Emerging evidence suggests that more men than women are dying, potentially due to sex-based immunological or gendered differences, such as patterns and prevalence of smoking.” But keep in mind that “current sex-disaggregated data are incomplete, cautioning against early assumptions.” In other research, data from 1,000+ patients in China show that “41.9% of the patients were female.” (Guan and others 2020). But beyond these direct effects, most of the other impacts affect women negatively and disproportionately.

Wenham, Smith, and Morgan highlight that women will be more affected in places with more female health workers. In an analysis of 104 countries, Boniol and others (2019) show that women form 67 percent of the health workforce (see the figure below). In China, “an estimated 3000 health care workers have been infected and at least 22 have died” (Adams and Walls 2020). As the pandemic spreads, the toll on women health workers will likely be significant.

Figure. Gender distribution of health workers across 104 countries

Source: Boniol and others (2019)

Here are other areas highlighted by Wenham, Smith, and Morgan:

– School closures are likely to have a differential impact on women, who in many societies take principal responsibility for children. Women’s participation in work outside the home is likely to fall. (My colleagues Minardi, Hares, and Crawfurd have written about other impacts of school closures during an epidemic.)

-Travel restrictions will affect female foreign domestic workers. Of course, they also affect male migrants. The distribution will vary by country. Research by Korkoya and Wreh (2015) found that 70 percent of small-scale traders in Liberia are women, so domestic travel restrictions during the Ebola outbreak disproportionately affected women.

-Health resources normally dedicated to reproductive health go towards emergency response. During the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, for example, the “decrease in utilization of life-saving health services translates to 3600 additional maternal, neonatal and stillbirth deaths in the year 2014-15 under the most conservative scenario” (Sochas, Channon, and Nam 2017). In my own research (with Goldstein and Popova), we found that the disproportionate loss of health workers in areas that had few to begin with would likely lead to higher maternal mortality for years to come.

-When women have less decision-making power than men, either in households or in government, then women’s needs during an epidemic are less likely to be met.

Here are four additional concerns:

-Sexual health: During the school closures of Sierra Leone’s Ebola outbreak, “a reported increase in adolescent pregnancies during the outbreak has been attributed largely to the closure of schools.” (UNDP 2015). Bandiera and others find that in villages highly disrupted by Ebola, girls were “10.7 percentage points more likely to be become pregnant, with most of these pregnancies occurring out of wedlock.” A United Nations report gives an even higher estimate of 65 percent. The absorption of health resources by emergency response may also lead to disruptions in access to reproductive health services.

Many girls didn’t return to schools once they reopened, and there were increases in unwanted sex and transactional sex. (Notably, Bandiera and others also find that girls in villages where there were established “girls’ clubs”—safe spaces for teenage and young adult girls to gather and get job and life skills—before the epidemic experienced fewer of these adverse effects.)

-Intimate partner violence rises in the wake of emergencies: Parkinson and Clare document a 53 percent rise in the wake of an earthquake in New Zealand and nearly a doubling in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in the United States. Mobarak and Ramos find that in Bangladesh, increased seasonal migration reduces intimate partner violence, at least in part because women spend less time with the potential perpetrators of that violence. Travel restrictions may be expected to have the opposite effect.

-The burden of care usually falls on women—not just for children in the face of school closures, but also for extended family members. As family members fall ill, women are more likely to provide care for them (as documented during an Ebola outbreak in Liberia, with AIDS patients in Uganda, and in many other places), putting themselves at higher risk of exposure as well as sacrificing their time. Women are also more likely to be burdened with household tasks, which increase with more people staying at home during a quarantine.

-As Mead Over and I have discussed, health crises can trigger economic crises. Economic crises affect women disproportionately, particularly in low-income countries. Sabarwal and others found that men’s labor force participation remained largely unchanged during economic crises, whereas women’s labor force participation rose in the poorest households and fell in richer households.

-Last week, the World Health Organization declared that “this is the first pandemic caused by a coronavirus.” There have been more than 168,000 confirmed cases and more than 6,600 deaths in 148 countries as of publication of this blog. The impact of this pandemic will be felt for years to come. As women are often disproportionately affected by the follow-on effects of the disease, we have to make sure that we keep women’s rights and needs front and center in our responses. A first step in doing that is making sure that women are a central part of the teams designing those responses.

Contributed by David Evans, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, working on education, health, and social safety nets.

This post benefitted from comments provided by Susannah Hares, Megan O’Donnell, Emily Christensen Rand, and Rachel Silverman.

Original blog published on Center for Global Development website March 16, 2020, see here for the original posting

Reposted with permission from David Evans, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development

- Published in COVID 19, Healthcare

Those unprotected by the “economic stability shield”

This brief note raises two issues: First, the widening of gender inequalities in unpaid care work and second, the potential gendered outcomes of rising formal and informal unemployment in the affected sectors in Turkey.

Market production is at a halt, yet women are working overtime

What sustains human life, as we all know, cannot be maintained solely by market purchased goods and services. Our lives are constantly reproduced within households. The overwhelming majority of women are involved in the provisioning of the most indispensable items needed to sustain our lives and enhance their quality.

We are told that economies are experiencing a “sudden stop”. While some businesses temporarily close their doors, there is full capacity production ongoing at our homes. In technical terms, excess capacity in market production is rising, while women are working overtime. Some forms of housework now require more attention and diligence for hygienic purposes than ordinary times. Sterilizing market purchased goods, washing the clothes and cleaning the house more frequently are now necessary. The shutdown of nurseries, kindergartens and schools increased childcare work burden. Adult and elderly care burden also increased. Turkey has banned people aged 65 or older from leaving their homes on March 21 and people aged 20 or younger very recently. These developments significantly increase women’s workload. The family has already been central to the welfare regime of Turkey. Care of children, elderly and people with disabilities have been overly dependent on families. We observe once again, the family-centered welfare regime shifts the care burden onto the families.

The unemployed and informal workers

As of December 2019, prior to the pandemic, nearly 4.3 million people were unemployed. It is assumed that approximately 9-10 million people will be unemployed after the pandemic. The unemployed and their household members–nearly half the population in Turkey—are at serious poverty risk.

“Economic Stability Shield” Package consists mostly of policies that aim to help the firm owners and ignores the most vulnerable segments: the long-term unemployed, first-time job seekers and the recently employed.

The other segment of the population overlooked by the Package is the unregistered or informal workers. More than five million workers, are working informally, and hence without social security, in Turkey.

It is clear that small and medium-sized companies, where informal work is widespread will be more adversely affected by the crisis. Accommodation and food (tourism sector at large), retail trade, and textiles and apparel will be most affected due to the pandemic. We estimate that 650 thousand informal workers in these three sectors are in danger of losing their jobs. In addition, over 700 thousand informal workers from the remaining sectors are estimated to lose their jobs.

The three sectors that are most affected by job losses make up almost a quarter of non-agricultural women’s employment. Even if we assume that there would be no employer discrimination and employers act in accordance with these current rates during layoffs, around 700 thousand women will lose their jobs, and around 190 thousand of those will not have any access to social security benefits since they have been working informally.

Our lives are upside down now and the future does not look bright at all. However, it is not the time to be pessimistic either. As we all know, all inequalities are socially constructed; their elimination will be too. If our struggle to rearrange our lives during and after this epidemic; will be towards more solidarity and towards an egalitarian society, we can start by deciphering all kinds of inequality, discrimination and exploitation inside and outside our homes.

This blog was authored by Emel Memiş, Department of Economics, Ankara University, KEFA and IAFFE member; Murat Koyuncu, Department of Economics, Boğaziçi University and Şemsa Özar, Department of Economics, Boğaziçi University, KEFA member, member and former president of IAFFE

- Published in Gender Inequalities, Turkey, Unpaid Work

COVID-19 is Testing the Norm: Gender Dynamics and Care in the Midst of the Pandemic

The COVID-19 crisis has upended lives around the world. It has forced cities and countries to enforce lockdown and social distancing regulations. Schools and businesses are closed and people are told to self-isolate, stay home, telework (if your job allows), to not go out except to get essential things, and care for each other but in distance. For those who live on their own, COVID-19 is about learning to live with solitude and loneliness, except for the occasional video, online or phone chats. For others who are living in a family, it is about living together in a confined space, 24/7, balancing work and family responsibilities, and rearranging the share of housework. The COVID-19 crisis is not just leaving a trail of human and economic sufferings; it is also testing prevailing gender norms as it confines both paid and unpaid work activities for many households within the same space.

Amongst the many lessons that the COVID-19 pandemic is teaching us, one of the most important is the centrality of care in maintaining a healthy, balanced and functional society and economy. Additionally, how much of that care is implanted in and shaped by our social and cultural norms. These norms vary by culture, class, caste, ethnicity, religion, and life cycle stage. Before the COVID-19, most of us had regular normal lives: during week days, children went to schools and adults either went to work or were looking for work. Frail elderly and disabled people were given necessary care by family members, relatives, domestic/ personal service workers or care service institutions. During weekends and holidays, social, religious, cultural, and leisure activities alongside weekend domestic chores filled people’s time.

But that was before the COVID-19; it is not the same anymore. The stay-at-home, social distancing and travel restrictions have forced household members to be physically together day and night. Without the vital and often taken-for-granted services such as daycares, after school programs, and community centre activities, and without opportunities to engage in social activities with other people, many households are suddenly faced with the challenges of having to both doing market work and care for their children as well as the sick, disabled, and frail elderly member needing care. It seems that the lived experiences of informal home-based women workers are now shared by millions around the world who have dependents: the constant juggling of different demands on one’s time and the stress of having to frequently multi-task. On one hand, there is the increased level of unpaid work that needs to be done, and on the other, the necessity to earn one’s livelihood from home. Many households therefore are faced with – for the first time – the imperatives of having to share the heavy burden of unpaid work. Will it be the usual division of household work as in ordinary “normal” times? Or will the situation at hand involve new negotiations and allow some upending of gender roles?

In unexpected ways, the COVID-19 health crisis has opened windows for women and men to see and experience the other “gender” role up close and personal: those not in the labor force see and hear the day-to-day business of earning a living ala “online”, while the “breadwinners” see and hear children needing attention, help with schoolwork, crying in the background, etc. In some households, men are now more willing to take on more care work, do the laundry, clean house and cook some meals. But in other households, the current situation may intensify existing unequal gender relations and heighten tensions. Male household heads for example, may deliberately utilize traditional gender norms to maintain discipline and control. For example, women are expected to find ways of combining childcare and market work by multi-tasking or lengthening their workday in order to reduce to the minimum any distraction or job interruptions to the head. In other cases, the angst associated with no social contacts or support, employment-related anxiety and growing economic insecurity may lead to increased drinking, rising tensions and even domestic violence. Fearful of the loss of their masculine identity, men may reinforce women’s submission to patriarchal rules in the household. Unfortunately, the situation created by the COVID-19 limits the options for women to seek help when they face threats to violence or are victims.

As social norms continue to evolve and traditional gender roles within households are tested in varied ways, one thing is clear: the COVID-19 crisis is exposing, and disrupting, the core system that supports our society and underpins our economy – the mixed economy of care. In ordinary or “normal” times, our lives are made manageable and our economy sustainable because different social institutions are providing different kinds of care in both paid and unpaid forms. These include public and private institutions, such as schools, hospitals, community centers and other social and community services providing essential health, education, and other social services; within the household (mainly women) doing unpaid essential care and domestic work. We take for granted this care delivery system, especially those institutional arrangements involving unpaid labour. We forget that care collectively provided by all these institutions play an important role in supporting us socially and economically. The COVID-19 crisis is teaching us that we are all socially and economically interdependent: we all give and receive care throughout our lives, and that we must recognize, understand and find ways to ensure that care work is valued. It is also giving us the opportunity to reflect on how the responsibility for and the cost of providing care can be better shared within households as well as within society – and on how we might better restructure our mixed economy of care.

This blog was authored by Ito Peng and Maria Floro

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities