Investing in Quality Care has Positive Macroeconomic Effects

Recent research by Lenore Palladino and Chirag Lala of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts Amherst, examines the effects of critical public investment in childcare, home health care, and paid family and medical leave (PFML) for the U.S. workforce, as proposed by the American Jobs Plan and the American Family Plan by the Biden-Harris Administration.

The authors find that investing in childcare and home health care workforce has positive macroeconomic effects, and the care workforce spends its own money on goods and services through the rest of the economy. They also find that PFML positively boosts the economy, as workers spend the wage replacement income they earn.

The authors model the effects of a $42.5 billion annual investment in childcare and a $40 billion investment in home health care with a minimum wage of $15 an hour and find that the proposed investment can create 564,000 additional jobs throughout the economy, and results in an increase in labor income of $82 billion annually. They find that universal paid family and medical leave, as proposed by the American Families Plan, would increase household income nationally by $28.5 billion, of which $19 billion would be wage replacement directly from the paid leave program, and $9.4 billion would be income earned by workers throughout the economy as people receiving wage replacement spend money on goods and services. This means that for every dollar spent on wage replacement as part of the paid leave program, other workers would earn an additional $.50.

RESEARCH BRIEF: The Economic Effects of Investing in Quality Care Jobs and Paid Family and Medical Leave

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, program manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project.

- Published in Care Infrastructure, Child Care, Elder Care, elderly care, Gender-Equal Economy, Healthcare, Macroeconomics, Policy

Caregiving in Crisis and How to Fix It: Special Issue from The American Prospect

Last month, the Prospect released a special issue featuring a series of articles surrounding family care,“Caregiving in Crisis and How to Fix It.”

To accompany this issue, a special event was hosted by the Prospect in which various activists, writers and caregivers discussed family care, child care, elderly care, paid family leave to provide care, and long term support for caregiving services.

This event featured:

David Dayen, executive producer for the Prospect

Ai-jen Poo, co-director of Caring Across Generations,

Lynnea Redmon-Williams, a caregiver working fulltime

Tasmiha Khan, Prospect contributing writer

Rhacel Salazar Parreñas, Professor of sociology at the University of Southern California

Brittany Gibson, Prospect writing fellow

See the video below for the entire discussion:

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Long Term Care Sector, Special Issues

COVID, the Old and Canada-What’s Wrong With Us? A Massey Dialogues Discussion

A recent virtual presentation from Massey College, “The Massey Dialogues: COVID, the old and Canada – What’s wrong with us?” brought together a panel to discuss how the detrimental impacts of COVID-19 in Ontario and Quebec fall alarmingly onto the elderly population. In fact, 80 per cent of pandemic deaths in Canada have occurred among the institutionalized elderly, the highest proportion in the world.

Ito Peng joins this conversation as a special guest to discuss the pandemic and its impact on Canada’s Long Term Care (LTC) sector, and ways through which the dominant thinking around market value/productivity neglects to value the work that older adults have already contributed to the economy throughout their lives, and fails to recognize their role as keepers of history and caretakers themselves.

In this discussion, Ito Peng is joined by Massey Fellows Dorothy Pringle, Husayn Marani and Michael Valpy.

- Published in COVID 19, elderly care, Expert Dialogues & Forums

LTC Sector Faces a Number of Challenges, Today and Going Forward: An OECD Report

OECD Health Policy Studies has released a 2020 report “Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly.” This report addresses a number of important issues while acknowledging the tremendous impact that COVID 19 has had on elderly people and their caretakers. Across OECD countries, more than one out of every six individuals is above the age of 65, and of those roughly 60% live with multiple chronic conditions, making them even more susceptible to the potentially deadly impacts of the virus. Furthermore, many elderly individuals struggle with sufficient access to social support and lack the ability to properly deal with the mental strain of living in a world being affected by a global pandemic.

Beyond these strains, there is a crisis in workforce shortcomings of the Long Term Care (LTC) Sector, which becomes even more problematic in light of the fact that an estimated 50% of COVID 19 related deaths are occurring in LTC facilities. This OECD report begins by addressing many of these shortfalls within the LTC sector, and policies that have the potential to address them.

Within three-quarters of OECD countries, the aging population has outpaced the workforce within the sector since 2011. This is the case even in the countries that have a higher workforce supply than the OECD average such as Japan and the U.S. Within the sector, women make up 90% of the LTC workforce. Attracting a younger workforce has been particularly difficult, and on top of that maintaining workers over the age of 50 is also a challenge. This is even more concerning given that the median age of LTC workers is currently 45.

Many OECD nations have made moves toward relocating their elderly out of facilities and back into the community. This is provoked by the desire to match the preferences of their elderly populations with home-based care, in addition to containing LTC spending. However, a lack of home-based workers has made this challenging, and LTC institution-based workers remain representative of the sector’s workforce across the OECD. This is in large part due to the fact that these institutions cater to the most disabled, which requires a larger workforce. Furthermore, many community-based solutions are not yet equipped to take in these types of complex cases.

The aging of the postwar “baby boom” generation is a factor that will contribute to the increased need for LTC workforce. This also contributes to the predicted increase in labor shortages in the sector to meet the needs of this population going forward. Further, unpaid informal care workers, like that of family members that would care for this aging population, have seen an increase in their own professional workload burdens. When the workload of professional life and caretaking becomes too great, LTC facilities are a means in which to relieve some of that strain. Additionally, as birth rates decline, families become smaller and more women are pursuing professional endeavors, the availability of informal caregivers for the aging population decreases looking into the future. This contributes to another foreseen LTC workforce shortage in the future.

These shortages call for an increase in recruitment within the LTC sector. As the sector workforce ages, attracting younger workers has proven difficult as they, mostly women, are drawn to sectors that have a more appealing image such as a child or hospital care. Additionally, LTC jobs are still widely considered to be feminine positions, and the sentiment on this subject matter has been slow to change.

Foreign-born workers play a significant role in recruiting and retaining LTC workforce. They are highly over representative within LTC across the OECD when compared to other care sectors, and many of them are young, Often, they tend to come into the sector with high levels of skill sets, even overqualified. Micro-econometric analysis has shown that in the U.S. and the UK, these foreign-born workers have higher retention rates than others within the sector.

In terms of recruitment, drumming up interest in the available positions is also problematic. In some cases, many vacancies receive no applications at all. On top of this, recruiters often have a difficult time identifying qualified candidates out of those that do apply.

In order to address this, many countries have focused on four main policies:

– Target recruitment to the traditional pool

– Improve the Image of the sector

-Recruit outside the traditional pool

-Increase the recruitment of for foreign-born workers

Overall, better policies are needed in order to improve recruitment within the LTC sector, and thus far few OECD nations have implemented policies in order to do so. By addressing these issues addressed within the first section of this report, there is potential for effective improvement.

- Published in elderly care, Long Term Care Sector, Policy

Biden’s Care Plan Has the Potential to Change Care Work in the U.S. for the Better

Joe Biden has officially accepted the Democratic Presidential nomination, and he and his team plan to make substantial investments in the infrastructure of care in the U.S. if he wins in the Presidential election. The potential of this plan to provide much-needed support for care workers, both paid and unpaid, is more important than ever amidst the pandemic.

Even prior to this pandemic, the U.S. has long suffered a caregiving crisis. Family caregiving needs often come with incredible financial, emotional, and professional burdens. Professional caregivers, disproportionately women of color, have long been underpaid and undervalued. The pandemic has exacerbated these issues, leaving parents struggling to find the care services needed while juggling careers. There are a number of measures that have been proposed by the Biden team to address the many issues currently plaguing the overall care system in the U.S. today.

Elderly individuals in nursing homes are feeling an increasing need to be cared for at home rather than in community living situations where they are more vulnerable to COVID-19 exposure. The Biden care plan addresses this by aiming to close the existing Medicaid gap to allow for home and community-based care services while creating a state innovation fund for cost-effective direct care services. This will provide more affordable and accessible care on that front. This step will also help to alleviate the extensive waitlists now existing for those under Medicaid to enter home and community care programs, providing these services for 800,000 individuals. If implemented properly, this initiative allows the opportunity to provide more functional care systems that grant greater independence to elderly individuals, while also freeing many unpaid care workers, such as family members, to pursue professional endeavors.

This plan also proposes increasing wages and benefits for caregivers and early childhood educators while providing opportunities for training, professional growth, and unions. This particular initiative takes into consideration the fact that early childhood development is incredibly important, and quality childcare is essential for children to grow into healthy, productive members of society. Universal preschool will also be provided via tax credits and sliding scale programs. Furthermore, included is an investment into safe and developmentally appropriate childcare facilities, including bonus pay for those providers that operate non-traditional hours, such as early mornings, late evening, and weekends. By increasing access to childcare centers with more flexible hours, the burden for many families will be lifted; currently, many parents that don’t work traditional Monday through Friday hours are left scrambling to find adequate care. These initiatives overall will have significant positive impacts on working parents, particularly women. Far too often, women find themselves sacrificing professional progression and development due to the constraint of inadequate or unaffordable childcare.

For those parents who grapple with the decision to further their education as a result of unaffordable and reliable care, investment in childcare centers at community colleges is also included in this plan.

Lastly, expanding the awareness of the Department of Defense fee assistance childcare programs so that all military spouses have the ability to pursue their professional development and education.

In order to pay for these initiatives, the Biden team has estimated a cost of $775 billion over the span of ten years, to be funded by rolling back certain tax breaks for those earning over $400,000 annually. A $5000 tax credit or Social Security credits for those providing unpaid care for members of their family is also proposed. Further, the plan seeks to offer low- and middle-class families up to $8000 in tax credits to assist in paying for childcare. For those that choose not to claim this credit, high-quality care is to be provided on a sliding scale, where it is estimated that families will not pay over $45 per week.

Although this plan is incredibly ambitious, and its implementation is not a guarantee, it sets a precedent that has been long lacking within the U.S. care work sphere. Implementation of these initiatives on any scale would prove beneficial to both the paid and unpaid care economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy, U.S.

Reflections on Parental Caregiving and Household Power Dynamics

A growing concern in many countries is an aging population and an increase in the number of elderly in need of long-term care. However, the impact of elderly care on the well-being of care providers remains relatively understudied. One of the primary factors which complicate analysis is that a majority of elderly care is provided informally by family members, with adult children often comprising the largest share of care providers. The pervasiveness of unpaid care due to cultural or family ties has even limited the development of long-term care insurance in economically advanced regions like Europe. However, while children may provide an informal safety net, parental caregiving is a time-intensive task and must be met by adjustments in leisure or work hours on the part of the care provider. Hence, in order to understand the full macroeconomic implications of growing elderly care needs and the appropriate policy response, it is imperative to understand how households cope with these caregiving needs.

Economic models of elderly care have focused almost exclusively on inter-generational bargaining between parents and children or bargaining among siblings. However, little attention has been paid to the influence of care demands on the power dynamics between partners within a household (e.g. husband and wife). This is despite data showing that caregiving falls disproportionately on women and that some caregivers respond to increased parental care needs by reducing work hours, taking more flexible jobs, or by quitting paid work entirely. Moreover, caregiving may have spillover effects on the caregiver’s spouse or partner. For example, a spouse may work longer hours or reduce their spending to cope with fewer hours of paid work by the caregiver. So it is unclear to what extent partners reallocate their time and resources and share the burden of parental care needs when they arise.

In the study detailed in the CWE-GAM working series paper published May 2020, we develop a theoretical model to explore how unpaid parental caregiving can affect the allocation of time and resources across partners under different household power structures. As parental caregiving disproportionately falls on daughters, we consider a model in which a woman’s parent is in need of time-intensive care. The provision of care across partners is then a bargained outcome between the couple. We not only examine how power dynamics and work arrangements impact caregivers and their partners but also how these factors may influence unmet care needs and care recipients.

After developing our model, we use cross-country data from the Survey of Health, Age-ing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) to illustrate our theoretical concepts with some numerical exercises. Broadly our results indicate caregivers may face a “triple burden” of market work, domestic chores, and caregiving. For example, our model predicts that for a duel-earning couple in France, the total cost of unpaid parental caregiving to the male is only about 57% that of their female partner—a skewed but shared burden. The higher cost to the female stems from two sources; (1) relatively fewer hours of leisure due to her provision of unpaid care; (2) the additional mental or emotional cost of leaving her parent with some level of unmet care needs.

Overall, our theoretical and numerical results show that ignoring bargaining power differentials across partners can misrepresent the true cost of unpaid parental caregiving by not taking into account the uneven distributional consequences. Moreover, our cross-country findings suggest that lower female bargaining power results in a larger burden on female caregivers and additional unmet care needs for their parents. If bargaining power is determined by relative earnings, government policies subsidizing long-term care could decrease the well-being gap within a household by providing financial relief and improving the bargaining position of the caregiver. This could further result in reduced levels of unmet care needs and improved outcomes for elderly care recipients. We further show that inflexible work arrangements also exacerbate the total cost of unpaid caregiving to the household as well as the unequal distribution of the burden. This implies policies that promote flexibility, such as caregiver leave or part-time options, could provide substantial relief, particularly to high-intensity caregivers.

This blog was authored by Ray Miller and Neha Bairoliya, who are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in elderly care, Rethinking Macroeconomics

The Unpaid Care Work and the Labor Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys

How much time do people spend on doing paid and unpaid care work? How do women and men spend their time differently on unpaid care work? Are there any differences in time use among the regions? How do socioeconomic factors influence people’s choices to do paid and unpaid care work?

Jacques Charmes addresses these questions in recent ILO report by providing a comprehensive overview of the extent, characteristics and historical trends of unpaid care work. The report is based on the analysis of the most recent time-use surveys carried out at the national level across the world, revealing the differences in time spent on unpaid care work between women and men and among people with different socioeconomic characteristics, such as geographical location, age and income groups, education level, marital status and the presence and age of children in the household. An insightful discussion of the concepts and methodological approaches underlying the analysis of time-use data is also offered.

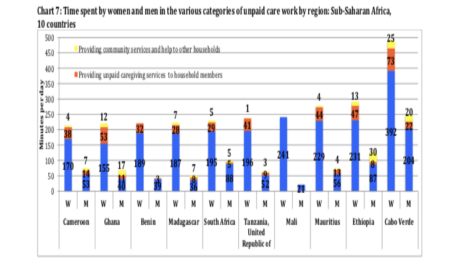

Chart 7 in the ILO Working Paper the Unpaid Care Work and the Labour Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys illustrates the time spent by women and men in various categories of unpaid care work across Sub-Saharan African countries including Cameron, Ghana, Benin, Madagascar, South Africa, Tanzania, Mali, Mauritius, Ethiopia and Cabo Verde. As with the case around the world, women in Sub-Saharan African countries are providing significantly more unpaid care services in households and communities. Read the report to learn more about time-use analysis concepts and methodologies, gender variations in paid and unpaid work across the world and across various socio-economic levels:

International Labour Organization

Gender, Equality and Diversity & ILOAIDS Branch

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy Briefs & Reports

Are We All Care Workers Now?

Who, exactly, are care workers, other than the people we need most right now, as the covid-19 pandemic overlays the division of labor with a new division of risk?

I’ve long been an advocate of using the term “care worker” rather than “caregiver” even though the work can be and often is, at least in part, a gift. Because care–whether performed for pay, or not–is at the crux of any sustainable economic system. All work depends on the successful production and maintenance of workers themselves. Yet because this very notion of care-as-work is relatively new, there is little agreement on its exact boundaries.

When I first started pursuing this issue with Paula England, we emphasized hands-on or face-to-face work that develops the capabilities of the care recipient, an essential aspect of the services that health care providers, workers, child care and elder care workers provide. This emphasis could be translated into a specific list of Census-designated occupations, grounding empirical research on the relative pay of care workers that has revealed significant pay penalties for both women and men in such occupations, controlling for many other variables such as education, experience, and unionization.

I liked this broad definition because it spanned paid and unpaid work, low-wage and relatively high-wage occupations, women and men, creating potential for new political alliances. Sociologists initially embraced the definition with some enthusiasm. Not so, economists, and Robert Solow, who attended some meetings of the Russell Sage Foundation Network on Care Work, pushed us for more specificity.

I felt some affinity with Kenneth Arrow’s insistence on the limits of markets and with efficiency-wage theories pointing to the difficulty of monitoring worker productivity, so added another twist to the definition: work in which concern for the welfare of the care recipient is likely to affect the quality of the service provided. In other words, work not performed entirely for money, akin to what some economists have termed “public service motivation” but more…personal.

Still not quite right. Sociologist Mignon Duffy has argued eloquently in Making Care Count that this definition privileges what she calls “nurturant care,” deflecting attention from the drudgery of menial care tasks–the emptying of bed pans, cleaning of toilets, and mopping of floors often performed by the most disempowered members of society. “Dirty” work itself is devalued. Duffy’s work has nudged me to focus more on industry–the economic consequences, for instance, of being employed in health care, education, or social services, regardless of occupation.

The pandemic, however, has pushed me over a cliff, because it is redefining the meaning of “dirty” work–now, any work that increases the risk of exposure to a potentially deadly virus: not just health care, child care, and elder care and unpaid care for family members, but also food services, package delivery, police protection, home repair services, garbage collection…the list goes on. We rely heavily on the motivations of such workers to minimize our own–as well as their own–chances of infection.

The entire sequestration/shelter-in-place/social distancing strategy relies heavily on good will and voluntary compliance. The very invisibility of covid-19 blurs the boundaries between love and money, us and them. The healthy now may later be sick, the sick now may later be dead. When risk is shared, the overlaps between solidarity and self-interest expand.

Yet so many boundaries, however blurry, remain in place. Whether because of who they are or what they do, some workers face much greater risks than others. It’s not enough to cheer them on, to offer them applause or a bit of extra cash.

If we are all care workers now we should do everything in our power to protect our own.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on April 4, 2020. See https://blogs.umass.edu/folbre/

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massechusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, elderly care

A Time for Reflection on Care

The world outside my study is churning and whirling… as it is engulfed with the fast-evolving health situations in communities around the globe. There are many unknowns about the

COVID-19 illness that has spread rapidly in every continent and the presence of uncertainty—big time—has rattled governments, shaken markets, and upended our daily routines, to say the least.

While I join the hundreds of millions of people who constantly check the news online and in newspapers, radio and/or tv, I also take time to pause. These moments allow me to reflect on

what this difficult time that we are all experiencing means and what it says about us—as

individuals, as members of communities, and as citizens of the world.

For one, I find that:

- each individual action has multitudes of rippling effects, large and small, on others;

- the real world oscillates between predictability and unpredictability; it requires each of us to constantly assess the balance between taking caution and taking risk;

- the distinction between self-interest and altruism (promoting others’ interests) becomes more blurred given the pervasive interconnectedness of our lives;

- adaptation and flexibility are vital life skills that we need to have not just now but at all times;

- we have the ability to change as we obtain more information and as conditions around us change; the notion of fixed tastes and preferences is outmoded;

- the skills that we must hone and develop should prepare us not only to live in a competitive world but also to be able to work together, coordinate and cooperate with one another; for the greater good requires collective action.

As the impacts of the COVID-19 spread intensify, there is growing recognition among governments and the public that traditional efforts for dealing with shocks and managing risks through conventional emergency responses are inadequate. Strategic thinking is needed as much as the ability to respond quickly and to take proactive measures. There is an urgent need to build the adaptive capacity and longer-term resilience of communities and societies.

One striking fact about the current global pandemic is its tremendous effect on the care sector. This includes not only the health care systems employing doctors, nurses, aides, and other health professionals but also the unpaid care labor provided by family members, neighbors, and kin.

Many are changing their daily life patterns to provide further assistance and care support for those who are vulnerable such as their parents or grandparents and for those who are self-quarantined. Many more are willing to take the risk of exposure to care for those who have tested positive and are ill but are staying at home because the healthcare system is inadequate, inaccessible, and/or overwhelmed. The shutdown of schools and daycare centers further adds demand for unpaid care. Parents are struggling to care for their children while at the same time trying to tele-work from home.

“How can I write or have meetings with my six-year old around?”

The cloak or mantle that hides the emerging crisis of social reproduction, or the under- provision of care for people who depend on it, is removed. This global pandemic exposes the heavy demand on those who carry the responsibility for providing care for the sick, the young and the frail elderly, the vast majority of whom have been women. It has upended preconceived notions such as: each individual is a ‘Robinson Crusoe’ in families that can find their own solutions to provide care, and that one’s ability to pay should determine who accesses care in the private sector.

The Care Work and the Economy Project joins the efforts of other organizations, research institutions and advocacy groups towards making the care sector visible to policymakers. The heavy care burden that is now being shouldered by health care systems, households, communities and countries throughout the world makes it imperative to bring care work out of statistical shadows and to remove the veil of ignorance in economic policymaking.

Let us hope that this time is truly different and that the jolt brought about by the current pandemic leads to more openness in the academic community and among policymakers towards a paradigm shift and policy change.

March 2020

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, elderly care, Maria Floro, Policy