Fellows Reflect on Intensive Course in Gender-Aware Macro Modeling

Last month, the Care Work and the Economy project partnered with the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College to host a three-week Intensive Course in Gender-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling taught in three time zones. The course aimed to engage our internationally diverse pool of Fellows to enhance capacity building in research and teaching of gender-sensitive economic analysis, focusing on care and macroeconomic policy aspects.

The course was built on four pillars:

1. Understanding and measuring the care economy

2. Adapting social accounting matrices to account for paid and unpaid care activities.

3. The use of information from time-use surveys on unpaid care activities with other relevant sources and information such as national income accounts, labor force surveys, and household or special surveys

4. Performing policy-relevant economic analyses that take systematic account of the interlinkages between care, macroeconomic processes, and distribution.

With 72 Fellows from 22 countries, including Colombia, Ghana, Mexico, Mongolia (to name a few), discussions around course material were perspective-rich and interdisciplinary. Reflecting on the course, many Fellows expressed the desire to integrate the teachings of the intensive course into their research agendas or current positions:

“I am delighted [to be a part of] a fantastic cohort and faculty who want to, and actually do, think critically about [macroeconomic] modelling in a gender-aware or feminist context…I am excited about the possibility of applying what I have learned to Cuban and Latin American contexts, [and] I would like to delve deeper into the Levy Micro-Macro model to analyze gender differences [in] the Ecuadorian context using time-use data.” — Anamary Maqueira Linares, Ph.D. student at University of Massachusetts, Amherst from Ecuador

“Inspired by Professor Folbre’s [lecture], I would like to conduct research using updated time-use surveys (such as the Mexican case)…I would like to explore the differences between time-use patterns in rural areas versus urban ones in Mexico and compare data from 2014 to the recent time-use survey in 2019. I am also organizing a workshop with the Mexican Statistics Agency [to explore] how the Mexican database was built (contrasted with other countries’ surveys) and promote its use among Mexican graduate students and policymakers.” — Dulce Guevara Lopez, consultant at the Mexican Centre for Innovation in Solar Energy

“It was interesting to learn how care and social reproduction interact with gender inequality in the labour market to determine economic growth/development. I think that [this would be] a good research perspective in the African context to see how household commodities and care-time interact with the gender segmented labour market to determine economic growth.” — Dr. Mamaye Thiongane, research associate at the Regional Consortium for Research in Generational Economy (CREG) and lecturer in economics at the Public Economics Laboratory (LEP)

“The discussions around the care diamond gave me a framework to think through the situation of community health workers in India. I plan to apply the Levy model and the care dependency ratio to the time-use survey for India. The course also helped me gather feminist insights to incorporate into the macro course that I teach at university.” — Dr. Anjana Thampi, assistant professor of economics at O. P. Jindal Global University, India

“The course was a fantastic deep-dive into the theory and practice of [macroeconomic] modelling for care, and sparked new ideas for my Ph.D. research. At a time when distances feel huge, the conversations and connections with lecturers and colleagues created a sense of closeness; something I will treasure this summer.” — Maria Sandoval Guzman, Ph.D. candidate in Economics at Curtin University in Australia, and scholar at the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre and the Women in Social Economic Research Cluster

This course has strengthened the network of researchers around the world dedicated to gender equality and proper care valuation; thank you to all Fellows, Instructors, and Facilitators for their contributions. To learn more about the course, instructors, and Fellows, click here.

This blog was written by Lucie Prewitt, research and communications assistant for the Care Work and the Economy Project.

CWE-GAM Scholars Leading Two Panels During 2021 IAFFE Annual Conference

This week, the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) will hold its Annual Conference: “Sustaining Life: Challenges of Multidimensional Crises” starting on Tuesday, June 22nd, and concluding Friday, June 25th. This conference will provide a forum for scholars to discuss feminist approaches to constructing “inclusive and resilient economic and political systems and [sustainting] our environment” in the context and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Care Work and the Economy Project will be leading two panel discussions on Wednesday, June 23rd and Thursday, June 24th: “Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” chaired by Elizabeth King and Ito Peng, and “Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” chaired by Young Ock Kim. In the discussions, CWE-GAM researchers will present gender-aware macroeconomic models, data collected from unique surveys of care providers and families, and microeconomic simulations used to better understand care work and the economy.

“Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” is scheduled for Wednesday, June 23rd from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time) and will contribute to ongoing efforts to “illustrate the intersectionality of care provisioning, economic growth, and distribution.” With an increasing need for care due to the rapid decline in fertility rates and aging population, South Korea offers a unique context to introduce models and analyze surveys given to households, child and eldercare workers.

There will be four papers presented in this panel:

“The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The Case of South Korea” by Cem Oyvat and Ozlem Onaran “introduces a post-Kaleckian feminist model to analyze the effects of public social expenditure and gender gaps on output and employment building on Onaran, Oyvat, and Fotopoulou (2019), and extending it with an endogenous labor supply and wage bargaining model.”

“The Quality of Life of Family Caregivers: Psychic, Physical, and Economic Costs of Eldercare in South Korea” by Jiweon Jun, Elizabeth King, and Catherine Hensly “examines the psychic, physical, and opportunity costs of caregiving within the family using data from a special-purpose national survey of 501 households conducted in Seoul in 2018.”

“Quality of Care, Commitment Level, and Working Conditions: Understanding the Care Workers’ Perspective” by Shirin Arslan, Maria Floro, Arnob Alam, Eunhye Kang, and Seung-Eun Cha uses “the 2018 Care Work Economy (CWE-GAM) survey data collected from 600 child and eldercare workers in South Korea [to] analyze patterns of commitment levels among [paid carers] in various settings such as private and public institutions as well as in homes of recipients by conducting tobit regressions and entropy econometrics for robustness checks.”

“Impacts of COVID-19 on Work-Family Balance in South Korea: Empirical Findings and Policy Implications” by Ito Peng and Jiweon Jun examines COVID-19’s unequal impact between men and women in South Korea using data from a survey distributed to “1,252 households with at least one child aged between 0 and 12 in June 2020 to find out how the first 2-month social distancing measure had affected their work, childcare arrangements, and their wellbeing.”

“Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” is scheduled for Thursday, June 24th from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time), which will share the results of gender-aware applied modelings and micro simulations for South Korea. The panel will discuss which fiscal policies are likely to be the most effective at reducing gender gaps in paid employment and which forms of public investment best contribute to reducing and redistributing unpaid work between genders and socio-economic groups.

There will be three papers presented in this panel:

“Child and Elderly Care in South Korea: Policy Analysis with a Gendered, Care-Focused Computable General Equilibrium Model” by Martin Cicowiez and Hans Lofgren presents the first care-focused and gendered model in the computable general equilibrium literature for Korea that “is built around a social accounting matrix (SAM) that covers non-GDP household services, singles out sectors for child and elderly care, and disaggregates households on the basis on care needs.”

“Care Support Ratios in Korea and the US” by Gretchen S. Donehower and Bongoh Kye takes a holistic view of care by including both paid and unpaid care for all age ranges and “create[s] [care support ratios] to understand the current care market and whether it is sustainable in the future…in two aging populations- Korea and the United States.”

“Towards a Caring and Gender-Equal Economy in South Korea: How much does the regulation of labor market working hours matter?” by Ipek Ilkkaracan and Emel Memis “use[s] a unique time-use survey on care arrangements by couples with small children in order to explore the potential of [the] reduction of full-time market work hours towards [the] narrowing of the gender gaps in paid and unpaid work.”

To learn more about the panels presented by CWE-GAM researchers and the IAFFE conference, please visit the IAFFE 2021 Annual Conference homepage and program.

This blog was contributed by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part II

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” The discussion describes the interconnections between the crisis of care, the deepening ecological crisis and growth and accumulation processes.

There are many common threads with the climate and ecological crisis and the care crisis. Significantly, the idea that economic growth is overall beneficial. The type of economic growth generally pursued worldwide has not only increased stresses put upon the earth’s resource base but also on care labor capacity, which is similarly but wrongly perceived to be of infinite supply. Moreover, arguments that equate economic growth with overall improvement fail to recognize the distributional element of rising income inequality, which is far more nuanced. In fact, among countries that are higher income, gains from economic growth within those nations do not trickle down to everyone. When looking at care, the widening income equality gaps has shifted distribution of care givers across social classes and national boundaries. As a result, the quality and adequacy of care within a single nation can be very different, which exacerbates differences in social reproduction.

At the same time, income inequality has created a solution for the care needs of those that have the means to hire care for children and elderly, because care workers in those sectors are often paid low wages. But for the working poor, hiring care work help is inaccessible due to financial constraints, therefore they rely on their kinship networks to help provide this care. Furthermore, much of the care work burden still falls on women even as they enter to labor force. Economics and social policy in many parts of the world continue to neglect the heavy work burden put upon women and the necessity to balance household care activities and market work. What can also be observed is a global care supply chain, with the migration of women and girls to urban areas to provide care for wealthier families. Care itself is becoming one of the drivers of income inequality.

The economy is not all about material production; it is really about human vision and social provisions. However, an illusion has been created that unpaid care work is a natural resource that serves as an input for market production to promote GDP growth. However, this idea does not take into account that the wellbeing of people, especially the elderly, the sick and children should be an end in and of itself, to achieve sustainable growth. There is much work to be done to address these issues. To begin, economists must envision long term horizons that look forward to future generations while also taking into account the interdependence of life and moral responsibility. They must also integrate care and environmental consequences into our economic policy tools. Overall a new economic paradigm that includes green ecology and feminist economic concerns is needed.

Link to Part 1 of this blog here.

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part I

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” This discussion delves into the foundation of project itself, its context, the analytical tools utilized in the research, as well as the external factors that have served as the catalyst for the work being done.

The Care Work and the Economy Project was developed after a group of feminist economists observed that in the effort to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes, as laid out within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, there were aspects of care work that needed to be addressed. The project includes 35 scholars from all around the world that are working to develop innovative analytical tools. The research has been applying and testing these tools in South Korea, a country that quickly industrialized in the 70s and 80s and therefore witnessed a very rapid demographic change in fertility and life expectancy.

The care economy, which is inclusive of caring for those that cannot care for themselves, underpins the production of all economies within society. This begins with the fact that if people stopped having children, which require care, then the economy would come to a halt due to lack of labor force. Generally, care work has a tendency to be undermined through a lack of gender awareness in macroeconomic modeling, which does not address care needs in any adequate manner. This aspect is also neglected within the policy making discourse, with the current economic paradigm failing to take into account the necessity for care work to achieve economic growth.

Economic models that display growth also fail to take into consideration social elements, making the assumptions that, for example, children will be cared for despite the lack of social investment into care. However, with care work there comes social, political and economic significance. The Care Work and the Economy project is working to demonstrate what a care focused macroeconomic model can reveal through the implementation of the analytic tools being developed and implemented through the research.

The absence of the care economy within macroeconomic models is in large part due to it being “invisible” since the work often unpaid. This has led to the neglect of care needs despite unpaid care work providing indispensable services in terms of economic activity and growth. The result is an emerging care crisis that has manifested itself in terms of uncared for elderly, sick and children. Furthermore, the crisis has provoked a form of silent protest against long unpaid work hours performed by women, leading to a decline in marriage and fertility rates. This in turn has resulted in a reproduction crisis.

The Care Work and the Economy project researchers are developing and using innovative analytical tools to bring care to the forefront, along with a deeper understanding of the nature of care work, while illustrating the intersectionality between care provisioning, economic growth and distribution. Although these analytical modeling tools are currently being applied in South Korea, the project believes they can be adopted and implemented into other countries as long as the provision of care is taken into context of those countries. The project research shows that governments have an important role and duty to invest in care provisions as well as comprehensive national care plans. One of the key findings is that it is important to take into account demographic change and climate change along with economic and structural changes taking place in policy making. This is a tall order but necessary to sustain economies and provide a future for next generation.

Link to Part 2 of this blog here.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

A Gendered Social Accounting Matrix for South Korea

A social accounting matrix (SAM) is an economy-wide consistent representation of the payments in an economy, linking production, primary factors, and institutions (the latter often split into households, government, and the rest of the world). In the words of Round (2003), “it is a comprehensive, flexible, and dis-aggregated framework which elaborates and articulates the generation of income by activities of production and the distribution and redistribution of income between social and institutional groups.” Most of the time, a SAM refers to the economy of a country for one year. It may be used to describe the structure of an economy and as a data input to economic models, most importantly CGE models. This paper documents a gendered Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) for South Korea for 2014: the steps followed in its construction, the data sources, and what the SAM says about the economic structure of this country (for brevity from now on referred to as Korea), including gender, time use, and the role of households in providing care and other services provided by households. The SAM that is presented is the key data input to a forthcoming analysis of gender and care in Korea’s economy based on GEM Care, a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model.

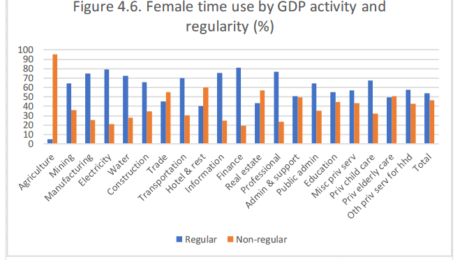

At an aggregate level, the value-added in the GDP economy is roughly 86 percent of the total (with agriculture, industry, services accounting for 2, 33, and 51 percent, respectively) and the non-GDP economy 14 percent. This information may be contrasted with aggregate time shares in terms of which, the non-GDP economy accounts for a much larger share, 40 percent. If leisure also were included, then it would on its own account for 50 percent of total time, 53 percent for men and 47 percent for women. The share of time allocated to household activities are drastically different for men and women, 15 and 57 percent, respectively. For women, non-care household services comprise the largest time using activity by a wide margin, followed by household childcare, trade services, and hotel and restaurant services. For men, manufacturing dominates, followed by trade services, household non-care services, and construction. For agriculture and industry, the lesser educated dominate all activities except electricity for both men and women. For services, the differences across sectors are drastic with some dominated by those with high education and others by those with low. These are few of the many descriptive findings from the gendered SAM developed by the authors.

This paper will be available December 2019.

This blog was authored by Binderiya Byambasuren, Kijong Kim & Hans Lofgren

Policy Analysis in a Macroeconomic Model of Social Reproduction

Since the 1990s, unpaid work and care have garnered increasing academic attention, creating the emerging fields of the economics of unpaid work and the study of “the care economy.” Most of the earlier work was oriented toward microeconomics, focusing on issues such as the household division of labor, subsistence production in developing countries, the substitution between non-market and market goods and services in households, and the role of caring motivations in sectors of the labor market in developed and developing countries. Empirical work paralleled these theoretical efforts. Examples include measuring unpaid work via time-use surveys across the world, estimating the monetary value or opportunity cost of unpaid work, and linking care with the gender–wage gap and gendered job segregation. Macroeconomic models exploring gender and economic development were rare, and even fewer macro studies examined care and unpaid work.

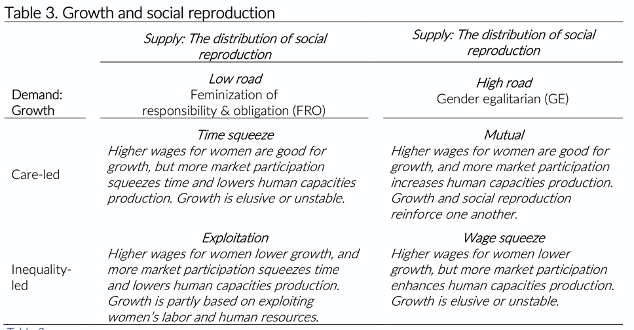

Braunstein et al. (2011) contributed to this literature by embedding unpaid work and care in a structuralist macro model, illustrating how the social structures of production matter for economic outcomes. Braunstein and Tavani (2019) recast a simplified version this model in order to generate policy implications through numerical simulation. The authors go beyond the standard utilization-labor share framing in structuralist models in order to focus on more direct measures of gender inequality and the gender composition of the labor force and of employment. The resulting producer’s equilibrium – which describes the supply side of the model – always features a positive relationship between economic activity and gender wage equality. The goods market equilibrium, or the investment-savings curve, can either be care-led or inequality-led. The model results accommodate a variety of scenarios. A reduction in non-market care time can foster both aggregate demand and gender equality, but under some conditions it is also possible that there are trade-offs between economic activity and gender equality.

This paper will be available in December 2019.

Impact of Investing in Social Care on Employment Generation, Time- and Income-Poverty and Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation for Turkey

CONTRIBUTORS

İpek İlkkaracan, EMEL MEMIS, KIJONG KIM, TOM MASTERSON, and Ajit Zacharias

Feminist economists have long emphasized the recognition, reduction and redistribution of unpaid care work (the so-called 3R strategy) as a primary policy intervention towards closing of the gender economic gaps. Investing in a social care infrastructure is an important component of the 3R strategy. Universal access to quality care services enables reduction of the unpaid work burden through its redistribution from the domestic sphere to the public sphere. Public investment and expenditure, however, is a question of fiscal policy at the helm of macroeconomists and policy-makers who are often gender blind and also adopt the mainstream approach of public expenditure constraint. Several waves of empirical research have examined the allocation of sectoral allocation of public expenditure through macro-micro simulations.

Yet until recently, studies have failed to explore an important outcome of investing in social care from a gender perspective, namely gendered patterns of time allocation. While investing in social care creates jobs for some women, enhances their access to employment and earnings, it also increases the requirements on their time through higher paid work hours. Simultaneous access to services alleviates the unpaid work burden of women with care dependent household members. The net welfare impact for different groups of women and men taking both time- and income-effects into consideration is an empirical question.

The forthcoming paper titled “Impact of Policy Interventions at Reduction and Redistribution of Unpaid Care Work On Employment Generation, Time- And Income-Poverty And Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation For Turkey” by Ilkkaracan, Kim, Masteron, Memis, and Zacharias uses an applied macro-micro simulation policy modelling approach to explore the gendered impact of increased public expenditures on social care service expansion on new employment and income generation, time allocation to paid versus unpaid work, time- and consumption poverty. An increase in social care spending triggers two types of effects at the household and individual level: It generates new jobs improving access of previously non-employed persons (predominantly women) to employment and income generation, but at the expense of increasing paid work time of job recipients. Simultaneously, improved access to childcare services reduces unpaid work time in the households with small children. The authors use a statistically matched data set from the 2015 Time Use Survey (TUS) and the Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) in Turkey to assess the impacts on individual and household well-being, not only in terms of gains in employment and income, but also in terms of potential changes in household production responsibilities and time deficits.

The paper will be available December 2019

The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The case of South Korea

According to the Global Gender Gap Index of the World Economic Forum (2018), South Korea is one of the lowest ranked countries in the world in terms of “Economic Participation and Opportunity” (124th out of 149 countries) as of 2018. The Global Gender Gap Index also shows that South Korea ranks 88th in terms of female labor force participation and 121st in terms of gender wage equality for similar work. The average wages of women in South Korea are on average 36.7% lower than average male wages (as of 2012, own calculations based on World Klems (2014) database). These statistics reflect that there is a significant economic gender gap in South Korea despite the fact that the country is now classified as a high-income economy. Moreover, the underdeveloped care infrastructure and reliance on unpaid care labor of women is posing serious demographic and social sustainability challenges in an aging society.

Existing research on the effects of public spending show a stronger positive effect of public spending in social care and education on female employment as well as total employment compared to public investment in physical infrastructure (Antonopoulos et al., 2010; Ilkkaracan, Kim and Kaya, 2015; Ilkkaracan and Kim, 2018; De Henau et al., 2016; Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou, 2019a). These employment effects have further effects on the economy and the wellbeing of the society, as microeconomic studies across the board attest that a larger share of women’s income compared to that of men’s, is spent to satisfy the needs of the household (Blumberg, 1991; Antonopoulos et al, 2010; Pahl, 2000) and a possible increase in their income leads to increased spending on children’s education and wellbeing (Vogler and Pahl, 1994; Lundeberg et al. 1997; Cappellini, Marilli and Parsons, 2014). Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou (2019a) confirm this finding at the macroeconomic level for the case of the UK. These consequently have further demand and supply side effects on output, productivity and employment (Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou, 2019a; Seguino, 2017).

Oyvat & Onaran (2019) examines the short-run and medium-run impact of public spending in social infrastructure, defined as expenditure in education, childcare, health and social care on aggregate output and employment of men and women for the case of South Korea. They present a gendered Post-Kaleckian theoretical macroeconomic model. The authors estimate the macroeconomic effects of social expenditure using a vector autoregression (VAR) analysis for the period of 1970-2012. The results show that an increase in the public social infrastructure significantly increases the total non-agricultural output and employment in South Korea both the short and medium-run. Moreover, higher social infrastructure expenditure increases female employment more than male employment in the short-run and raises both male and female employment in the medium-run due to increasing aggregate output. Finally, estimates show that the South Korean economy is wage-led and gender equality-led in the short-run, hence overall equality-led, although the effects are economically small in comparison to the strong effects of increases social infrastructure spending, and become insignificant in the medium-run. The results indicate that sustainable equitable development and a substantial increase in employment requires a mix of both labor market and fiscal policies.

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in Gender-Aware Macromodels, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea

- 1

- 2