Child and Elderly Care in South Korea: Policy Analysis Using CGE Model

In Korea, fertility is constantly decreasing, and it is currently very low, the size of the elderly population is going up, and at the same time, the size of the child population is going down, the gender wage gap is the highest among the OECD countries at about 35%. Given this context, Dr. Martin Cicowiez (Universidad Nacional de la Plata) discussed a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model for South Korea developed with Hans Lofgren (World Bank) that assessed the impact of different policies related to childcare, elderly care, and the gender wage gap on the distribution of paid care and unpaid care in households, on the second day of the Concluding Annual Meeting.

Dr. Cicowiez stated that a well-structured and disaggregated model could capture the role of government policies in addressing these challenges and further inform policymaking by establishing links between care, female labor force participation, gendered wage discrimination, and social and economic outcomes such as household wellbeing.

The model features three representative households based on their care needs: working-age head with children, working-age head without children, and elderly head. And three simulations: increase in government spending on childcare, increase in government spending on eldercare, and a decrease in the wage gap by 50%. The results show an increase in time spent on paid work for both men and women if there is an increase in government spending on childcare and this increase is higher for females. The effects of increased government spending on elderly care and a decrease in the wage gap are similar but relatively smaller. All three simulations demonstrate a switch from unpaid care to market care services. It is worth noting that females experience decreased leisure when the analysis includes time spent on leisure activities. These results underscore the tradeoffs of macroeconomic policies targeted at care work.

To watch the full presentation, see below.

Written by Praveena Bandara, Research Assistant for the Care Economy Project and PhD student in Economics at American University.

- Published in Conferences, Economic Modeling, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics

CWE-GAM Scholars Leading Two Panels During 2021 IAFFE Annual Conference

This week, the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) will hold its Annual Conference: “Sustaining Life: Challenges of Multidimensional Crises” starting on Tuesday, June 22nd, and concluding Friday, June 25th. This conference will provide a forum for scholars to discuss feminist approaches to constructing “inclusive and resilient economic and political systems and [sustainting] our environment” in the context and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Care Work and the Economy Project will be leading two panel discussions on Wednesday, June 23rd and Thursday, June 24th: “Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” chaired by Elizabeth King and Ito Peng, and “Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” chaired by Young Ock Kim. In the discussions, CWE-GAM researchers will present gender-aware macroeconomic models, data collected from unique surveys of care providers and families, and microeconomic simulations used to better understand care work and the economy.

“Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” is scheduled for Wednesday, June 23rd from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time) and will contribute to ongoing efforts to “illustrate the intersectionality of care provisioning, economic growth, and distribution.” With an increasing need for care due to the rapid decline in fertility rates and aging population, South Korea offers a unique context to introduce models and analyze surveys given to households, child and eldercare workers.

There will be four papers presented in this panel:

“The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The Case of South Korea” by Cem Oyvat and Ozlem Onaran “introduces a post-Kaleckian feminist model to analyze the effects of public social expenditure and gender gaps on output and employment building on Onaran, Oyvat, and Fotopoulou (2019), and extending it with an endogenous labor supply and wage bargaining model.”

“The Quality of Life of Family Caregivers: Psychic, Physical, and Economic Costs of Eldercare in South Korea” by Jiweon Jun, Elizabeth King, and Catherine Hensly “examines the psychic, physical, and opportunity costs of caregiving within the family using data from a special-purpose national survey of 501 households conducted in Seoul in 2018.”

“Quality of Care, Commitment Level, and Working Conditions: Understanding the Care Workers’ Perspective” by Shirin Arslan, Maria Floro, Arnob Alam, Eunhye Kang, and Seung-Eun Cha uses “the 2018 Care Work Economy (CWE-GAM) survey data collected from 600 child and eldercare workers in South Korea [to] analyze patterns of commitment levels among [paid carers] in various settings such as private and public institutions as well as in homes of recipients by conducting tobit regressions and entropy econometrics for robustness checks.”

“Impacts of COVID-19 on Work-Family Balance in South Korea: Empirical Findings and Policy Implications” by Ito Peng and Jiweon Jun examines COVID-19’s unequal impact between men and women in South Korea using data from a survey distributed to “1,252 households with at least one child aged between 0 and 12 in June 2020 to find out how the first 2-month social distancing measure had affected their work, childcare arrangements, and their wellbeing.”

“Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” is scheduled for Thursday, June 24th from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time), which will share the results of gender-aware applied modelings and micro simulations for South Korea. The panel will discuss which fiscal policies are likely to be the most effective at reducing gender gaps in paid employment and which forms of public investment best contribute to reducing and redistributing unpaid work between genders and socio-economic groups.

There will be three papers presented in this panel:

“Child and Elderly Care in South Korea: Policy Analysis with a Gendered, Care-Focused Computable General Equilibrium Model” by Martin Cicowiez and Hans Lofgren presents the first care-focused and gendered model in the computable general equilibrium literature for Korea that “is built around a social accounting matrix (SAM) that covers non-GDP household services, singles out sectors for child and elderly care, and disaggregates households on the basis on care needs.”

“Care Support Ratios in Korea and the US” by Gretchen S. Donehower and Bongoh Kye takes a holistic view of care by including both paid and unpaid care for all age ranges and “create[s] [care support ratios] to understand the current care market and whether it is sustainable in the future…in two aging populations- Korea and the United States.”

“Towards a Caring and Gender-Equal Economy in South Korea: How much does the regulation of labor market working hours matter?” by Ipek Ilkkaracan and Emel Memis “use[s] a unique time-use survey on care arrangements by couples with small children in order to explore the potential of [the] reduction of full-time market work hours towards [the] narrowing of the gender gaps in paid and unpaid work.”

To learn more about the panels presented by CWE-GAM researchers and the IAFFE conference, please visit the IAFFE 2021 Annual Conference homepage and program.

This blog was contributed by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

Making Care Count

The COVID-19 pandemic has informed our understanding of the care economy, exposing disproportionate inequities that must be addressed to alleviate the international erasure of care workers. These issues are addressed in the latest Susan and Michael J. Angelides Lecture, in which Naomi Klein moderates a discussion between Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal and CWE-GAM researcher Dr. İpek İlkkaracan on COVID-19 and the care economy.

We live in an economic system that has traditionally deprioritized and invisibilized care workers, many of which are women of color, migrant, and poor women. The economic crisis brought on by the pandemic has consequently given policymakers and academics “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address [the valuation of care work] from an intersectional [approach],” states Congresswoman Jayapal.

The Care Crisis Exposed by the Pandemic Recession:

When mass unemployment hit during the pandemic, the cracks in the economic infrastructure of America began to show. As millions of people lost their jobs, the highest increase in the number of uninsured Americans was subsequently recorded. This high number of uninsured people is a direct consequence of healthcare being employer-sponsored. Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “Medicare For All would have strengthened the response to the pandemic…30 percent of COVID-19 deaths were related to a lack of insurance.”

While gains were made in the past decade in regards to gender equality in the workplace, Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “as soon as the pandemic hit, it was the women who went back to taking care of [their] families.” Dr. İpek İlkkaracan explains that this is because “the nature of women’s employment is often determined by their care responsibilities…unpaid care work is often articulated as one of the most significant barriers to labor force participation.” This notion was reflected in jobs reports—in December of 2020, women accounted for 100 percent of job loss, and within that, 154,000 Black women exited the workforce.

In its current state, the care economy produces a pattern of inequality that disproportionately affects women of color and migrant women. The average caregiver salary is $12.74, and the care work sector is marked by poor working conditions with no adequate social protections and low wages. This is why, as Congresswoman Jayapal notes, the fight for one fair wage is pertinent. “An increase in the minimum wage would give 32 million workers a raise, 60 percent of which are women while 1 in 4 of the women who would benefit from this increase are Black or Latina.”

A Framework for a More Caring Economy:

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan has developed a framework that acknowledges the care economy. This framework, coined as the Purple Economy (a nod to the color representative of many women’s movements), envisions a gender-egalitarian and caring economic system. Dr. İlkkaracan recommends “labor market regulations and investment in care services such as long-term care, early childhood education, education, and healthcare” as policy interventions to start the process of adequately valuing care.

Not only is investment in care important from a humanitarian and ethical perspective, but it is also conducive to economic stability. Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has revealed that investment in care services produces a high employment multiplier: for every dollar invested in care, three times as many jobs are created in the wider economy. This is because the care sector is intertwined with other sectors such as food, transport, and financial services. In the Asia-Pacific region, Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has shown that “up to four trillion dollars could be added to GDP if unpaid care work (75% of which done by women) was valued in market terms.” While this may seem astronomical, the amount of unpaid work completed globally in one day equates to 16.4 billion hours—which translates to two billion full-time jobs. Dr. İlkkaracan’s recent research also reveals that a “3.5-4% commitment of GDP to investment in care services would create 120 million additional jobs and have a large impact on poverty alleviation.”

To watch the full conversation and learn more about the Purple Economy, see below.

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan is a CWE-GAM researcher a part of the Rethinking Macroeconomics and Gender Aware Applied Economics Working Groups.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Gender-Equal Economy, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, U.S.

Reflections on Parental Caregiving and Household Power Dynamics

A growing concern in many countries is an aging population and an increase in the number of elderly in need of long-term care. However, the impact of elderly care on the well-being of care providers remains relatively understudied. One of the primary factors which complicate analysis is that a majority of elderly care is provided informally by family members, with adult children often comprising the largest share of care providers. The pervasiveness of unpaid care due to cultural or family ties has even limited the development of long-term care insurance in economically advanced regions like Europe. However, while children may provide an informal safety net, parental caregiving is a time-intensive task and must be met by adjustments in leisure or work hours on the part of the care provider. Hence, in order to understand the full macroeconomic implications of growing elderly care needs and the appropriate policy response, it is imperative to understand how households cope with these caregiving needs.

Economic models of elderly care have focused almost exclusively on inter-generational bargaining between parents and children or bargaining among siblings. However, little attention has been paid to the influence of care demands on the power dynamics between partners within a household (e.g. husband and wife). This is despite data showing that caregiving falls disproportionately on women and that some caregivers respond to increased parental care needs by reducing work hours, taking more flexible jobs, or by quitting paid work entirely. Moreover, caregiving may have spillover effects on the caregiver’s spouse or partner. For example, a spouse may work longer hours or reduce their spending to cope with fewer hours of paid work by the caregiver. So it is unclear to what extent partners reallocate their time and resources and share the burden of parental care needs when they arise.

In the study detailed in the CWE-GAM working series paper published May 2020, we develop a theoretical model to explore how unpaid parental caregiving can affect the allocation of time and resources across partners under different household power structures. As parental caregiving disproportionately falls on daughters, we consider a model in which a woman’s parent is in need of time-intensive care. The provision of care across partners is then a bargained outcome between the couple. We not only examine how power dynamics and work arrangements impact caregivers and their partners but also how these factors may influence unmet care needs and care recipients.

After developing our model, we use cross-country data from the Survey of Health, Age-ing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) to illustrate our theoretical concepts with some numerical exercises. Broadly our results indicate caregivers may face a “triple burden” of market work, domestic chores, and caregiving. For example, our model predicts that for a duel-earning couple in France, the total cost of unpaid parental caregiving to the male is only about 57% that of their female partner—a skewed but shared burden. The higher cost to the female stems from two sources; (1) relatively fewer hours of leisure due to her provision of unpaid care; (2) the additional mental or emotional cost of leaving her parent with some level of unmet care needs.

Overall, our theoretical and numerical results show that ignoring bargaining power differentials across partners can misrepresent the true cost of unpaid parental caregiving by not taking into account the uneven distributional consequences. Moreover, our cross-country findings suggest that lower female bargaining power results in a larger burden on female caregivers and additional unmet care needs for their parents. If bargaining power is determined by relative earnings, government policies subsidizing long-term care could decrease the well-being gap within a household by providing financial relief and improving the bargaining position of the caregiver. This could further result in reduced levels of unmet care needs and improved outcomes for elderly care recipients. We further show that inflexible work arrangements also exacerbate the total cost of unpaid caregiving to the household as well as the unequal distribution of the burden. This implies policies that promote flexibility, such as caregiver leave or part-time options, could provide substantial relief, particularly to high-intensity caregivers.

This blog was authored by Ray Miller and Neha Bairoliya, who are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in elderly care, Rethinking Macroeconomics

Reflections on The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment in South Korea

In terms of “Economic Participation and Opportunity” South Korea is one of the lowest-ranked countries in the world (124th out of 149 countries) as of 2018. Global Gender Gap Index also shows that South Korea ranks 88th in terms of female labour force participation and 121st in terms of gender wage equality for similar work. The average wages of women in South Korea are on average 36.7% lower than average male wages (as of 2012, Oyvat and Onaran, 2020). Hence, there is a significant economic gender gap in South Korea despite the fact that the country is now classified as a high-income economy. Moreover, the underdeveloped care infrastructure and reliance on unpaid care labour of women is posing serious demographic and social sustainability challenges in an aging society.

Our new research analyses the effects of public social expenditure in education, health and social care and closing gender pay gap on aggregate output and female and male employment (Oyvat and Onaran, 2020). We introduce a structuralist gendered model of the demand and supply sides of the economy with endogenous productivity, labour supply and wage bargaining. Empirically, we use a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) analysis to econometrically estimate the effects of an increase in social infrastructure spending, female and male wages, and closing the gender pay gap on aggregate output and employment of men and women in South Korea for the period of 1970-2012.

Public social expenditure, specifically education played an important role in the rise of South Korean economy. The social sector has not only been a sector that is crucial for economic growth in South Korea, but it has also been important for generating female employment and closing gender employment gaps. The share of women in employment in the social sector (education, healthcare and social care) has been greater than in the rest of the economy since the 1970s. The share of female employment in the social sector in South Korea increased from 47.4% during the period of 1988-1997 to 58.3% in 1998-2007 and to 63.2% in 2008-2012. In contrast, the share of female employment in the rest of the non-agricultural economy is only 27.7% in 1998-2007 and 28.4% in 2008-2012. The female employment share even in sectors which traditionally had a high female employment such as food, beverages, tobacco, textiles, leather, and footwear or electrical and optical equipment have been steadily declining and is lower than the female employment share in the social sector in the post-1998 period.

Our theoretical framework identifies the possible channels through which public social spending influences total output, male and female employment. In the short-run, the increase in public social spending has a positive effect on total output and female and male employment. While higher social public expenditure may increase public debt/GDP in the short-run, this negative effect is moderated as tax revenues also increase alongside aggregate income, which in turn offsets any potential crowding out effect on private investment. As the female employment share is significantly larger in the social sector than in the rest of the economy, higher public social expenditure is expected to reduce the gender employment gap.

In the medium-run, higher public social expenditure is expected to have not only a direct positive effect on labour productivity, but also an indirect positive effect through i) higher output and benefits of increasing returns to scale; ii) higher wages creating incentives for adopting labour-saving technologies; and iii) higher private expenditure in education, health and social care by the households as income, in particular female income increases. Due to these effects on productivity, we refer to public social expenditure as social infrastructure investment.

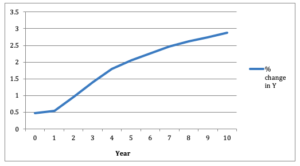

Figure 1: The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in social expenditure (YH) on aggregate non-agricultural output (Y)

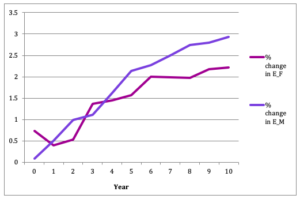

The estimation results show that a 1% increase in the public social expenditure in South Korea increases non-agricultural output by 0.5% contemporaneously, and by 2.3% in cumulative over six years and 2.9% over ten years (Figure 1). As a result female and male employment increase contemporaneously by 0.7% and 0.1% respectively (Figure 2). The short-run impact is larger for female employment as the share of women is significantly higher in the social sector compared to the rest of the non-agricultural sector. In ten years female and male employment increase by 2.2% and 2.9% respectively. Finally, labour productivity increases by 0.22% over four years.

Figure 2: The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in social expenditure (YH)on female (EF) and male employment (EM)

The results also show that an increase in female wage rate has a significant positive effect on output. A 1% increase in female wages leads to a cumulative increase in output by 0.2% in year 3 and by 0.3% over 10 years. This shows that the South Korean economy is female wage-led/gender equality-led in the medium-run; hence higher equality is conducive to growth and development. The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in the male wage rate on output is 0.2% over 10 years. It is also important to emphasize that higher male wages are not an impediment to growth in South Korea. The results also indicate the importance of improving gender equality as part of an equality-led development policy.

Our research shows that an equitable development path in which both average wages increase and gender gaps close via an upward convergence in the wages of men and women is possible in South Korea. However, the effects from wages are economically small in comparison to the strong effects of social spending. The results indicate that sustainable equitable development and a substantial increase in employment requires a mix of both labour market and fiscal policies.

This blog is authored by Cem Oyvat and Özlem Onaran are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea

Reflections on Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Growth

Despite notable progress in recent decades (including in primary school enrolment and access to the political system), gender gaps remain pervasive in rich and poor countries alike. In many developing economies, gaps in secondary and tertiary education, access to finance and health care, labor force participation, formal sector employment, entrepreneurship and earnings, remain large. In today’s low- and middle-income countries for instance, the labor force participation rate for women is only 57 percent, compared to 85 percent for men. Women’s share in the formal sector employment remains low and in recent years has even fallen in some cases. On average, women workers earn about three-quarters of what men earn. In Sub-Saharan Africa more specifically, women still have fewer years of education and fewer skills than men; and learning gaps remain large. Wage and employment gaps in certain occupations (particularly in managerial positions) and activities, and gaps in access to justice and political representation, also remain sizable.

In recent years formal academic research has shed new light on the causes of gender gaps and their consequences for economic growth. The mainstream analytical literature has identified several channels through which gender inequality may affect growth. One of them is the infrastructure-time allocation channel, which emphasizes the fact that, in addition to the conventional positive effects on factor productivity and private investment, improved access to infrastructure reduces the time that women allocate to household chores, and this may, in turn, allow them to devote more time to remunerated labor market activities. In addition, infrastructure may also have a significant impact on health and education outcomes, for both men and women, which may in turn affect their productivity, relative earnings, and indirectly the allocation of time within the family.

CWE-GAM working paper Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Growth further explores how improved access to infrastructure affects women’s time allocation decisions and how, in turn, changes in these decisions affect the process of economic growth in low-income developing countries. To do so it develops a simple two-period, gender-based overlapping generations model with public capital to explore the implications of public infrastructure on women’s time allocation and growth. The focus is on the specific impact of access to public infrastructure services (whose supply can be directly influenced by policy decisions) on female time allocation decisions between market work and home production, and its interactions with economic growth. As in some existing contributions, the basic model accounts not only for the standard productivity effect of public infrastructure but also for its effect on home production and occupational choices. In addition, the case where gender bias and bargaining power, as well as fertility choices and rearing time, are endogenous, and the case where there are two types of infrastructure, physical infrastructure (which includes transport, water supply, and sanitation, telecommunications, and energy) and social infrastructure (which includes the provision of maternal care), are also considered.

The analysis shows that by inducing women to reallocate time away from home production activities and toward market work, improved government provision of infrastructure services—assuming a sufficient degree of efficiency—may help to trigger a process through which a poor country may escape from a low-growth trap. This result is in line with those established in a number of recent contributions. It is also shown that with endogenous gender bias and bargaining power, there are two additional channels through which improved access to infrastructure can affect growth: positive effects on the level and rate of savings, which tends to promote growth. However, the increase in both the public and capital stocks implies that the net effect on the public-private capital ratio, and thus women’s time allocation, is ambiguous in general. This is due to the fact that higher private capital stock increases congestion costs, which tend to lower the public-private capital ratio. By implication, the net effect on gender equality in the market place, and economic growth, is now also ambiguous. Thus, improved access to infrastructure may not always be beneficial.

With endogenous fertility and child-rearing, improved access to infrastructure may raise the fertility rate and total rearing time, thereby mitigating the positive effect on women’s time allocated to market work. However, this effect is not robust. In addition, if there is a positive externality associated with improved access to infrastructure, this may lead not only to a reduction in time allocated to household chores but also to a reduction in total time allocated to child-rearing. In turn, this may lead to women allocating more time to market work, thereby promoting growth. Finally, the analysis highlights the fact that although the physical and social infrastructure is complementary at the microeconomic level, a trade-off exists at the macroeconomic level as a result of the government’s budget constraint. The optimal policy that internalizes this trade-off must account for the relative efficiency of investment in these two types of assets.

This blog is authored by Pierre-Richard Agénor and Madina Agénor who are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Gender Inequalities, Rethinking Macroeconomics

How I Learned to Love Macro

I have despised macroeconomics–even relatively innovative, post-Keynesian, gender-infused versions—for many years, for two big reasons. First, macro remains largely focused on an output variable, Gross Domestic Product, that systematically mismeasures the total value of material goods and services produced. Second, it treats the quantity of one of its most important inputs, labor, as exogenously given and/or relatively unimportant.

This is so wrong. Economies cannot be reduced to the production of commodities by means of commodities. They should be understood, more broadly, as the production of people by means of people. My collaborator James Heintz develops this critique in exceptionally clear and accessible terms in his new book The Economy’s Other Half. All of the participants in the Gender and Macro project under the rubric of the Care Work and The Economy project are, in one way or another, subverting the conventional paradigm.

They have actually taught me to love macroeconomics by showing how analytical models can enrich narrative accounts of social reproduction. I got so inspired that I actually sat in on a graduate course (taught by none other than James Heintz) and reviewed my calculus.

I went back and read some classic articles by Paul Samuelson and others explaining why intergenerational transfers (including the support and care of children and the elderly) cannot be organized by voluntary exchange.

James and I outlined some of the ways economists have conceptualized expenditures on children in a joint paper published in the Basque journal Ekonomiaz (also available on the Political Economy Research Institute website). Most recently, he took the lead on another joint paper that explains long-run macro models minimize the importance of demographic change (“Endogenous Growth, Population Dynamics, and Returns to Scale: Long-Run Macroeconomics When Demography Matters”).

It seems pretty obvious that models treating population growth as exogenous ignore the most important link between the family economy and the market economy. It is far less obvious that assumptions regarding constant returns to scale in production functions can have similar implications. Our paper explains why this is the case. It also develops an endogenous growth model that highlights the potentially negative macroeconomic effects of population growth rates that are either “too low” or “too high.” Microeconomic decisions don’t always magically lead to good macroeconomic outcomes.

The below-replacement fertility rates now common to many countries, including the U.S., Italy, Spain, Korea, and China, can potentially have negative macroeconomic implications, as can the high fertility rates characteristic of many sub-Saharan countries. In a sequel to this paper, we plan to develop its microeconomic foundations more fully, demonstrating the macroeconomic effects of public policies such as parental allowances and paid family leaves as well as changes in women’s bargaining power in the home. This model could also bring immigration policies into the macroeconomic limelight.

Who knew that macro could be so much fun?

Dr. Nancy Folbre is from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Rethinking Macroeconomics

Reflections on Microfinance and the Care Economy

With rollback of the developmental state under the neoliberal policy regime, financial inclusion has come to be adopted as a developmental strategy. Micro-credit schemes, which were initially promoted as tools for gender-empowerment and poverty alleviation, have in the process become increasingly absorbed within the sphere of mainstream private finance. The relatively low rates of default in this sector have attracted an influx of funds from profit oriented financial institutions. The focus has shifted from the sustainability of income generation for borrowers to that of the profitability of the lending institution. Given the higher transaction costs associated with small loans and extending outreach to marginal low income households this change of focus has undermined the social mission of microfinance to reach the poorest and most neglected households. Social priorities are being subordinated to commercial considerations.

The impact of micro-credit on both poverty and gender relations has been extensively studied. However, the implications of the growth of micro-credit for the care-economy, and their repercussions in the wider macro-economy have received less analytical attention. The neglect of the implication microfinance for the provision of care labor is surprising in the light of the original mission of microfinance, which targeted the female worker in rural areas in developing countries, with less access to earning opportunities and disproportionate responsibility for the care work. The increase in market labor implies a claim on the time of working women. In the absence of social provisioning of care, this claim on the labor time of women could lead to a squeeze on the time of rural working women

A simple two-sector post-Keynesian model allows the integration of the role of demand and care work into the analysis of microfinance. This investigation demonstrates is that micro financed enterprises face a structural constraint on the demand side from overall macroeconomic conditions, and on the supply side from the responsibility for unpaid care work borne by the female beneficiary of microfinance. Paradoxically, microfinance has been espoused as a developmental strategy in precisely the period when the role of the developmental state has been eclipsed, and cutbacks in public spending on care provisioning have been prescribed.

Slowdowns in the wider economy, would lower the demand for the output of the microfinance sector, and hence undermine the viability of these enterprises. The capacity of the microfinance sector to provide the impetus to broader demand growth in the economy is likely to be more limited in the absence of public policies to stimulate demand and investment. The capacity of microfinance to alleviate poverty and lift incomes is thus dependent on conditions in, and linkages with the wider macroeconomy. A vibrant and stable macroeconomy is the only sustainable basis for a stable microfinance sector.

We also draw attention to some of the complexities of the impact of microfinance on the provision of care. The home-based nature of microenterprises perpetuates the gendered asymmetries of care responsibility within the household. While higher female earnings can alleviate the burden of care by making care work more effective and by enabling the market to substitute for unpaid care, at the lower income levels and in a context of the inadequate social provision of care the gendered responsibility for care remains a critical constraint for the female beneficiary of micro-finance.

Some clear policy prescriptions emerge from this investigation. Donors and development agencies have been encouraging raising interest rates in order to ensure the viability and profitability of microfinance lenders. Our model suggests that high-interest rates will actually undermine the scope of microfinance as a path to better and sustainable livelihoods for poor households in rural areas. Higher interest rates in this sector impose a higher burden on the labor time of the female worker with a consequent squeeze of care-labor or the own labor time.

More significantly, the analysis suggests that microfinance cannot be an effective path to poverty alleviation or gender empowerment unless it is backed by investment in the social provisioning of care. The success of microfinance as a developmental strategy depends on wider policies that support demand and the social provision of care. There is, in the final analysis, no substitute for a developmental strategy based on public investment in support of both job creation and social provision of care.

This blog was authored by Ramaa Vasudevan and Srinivas Raghavendran are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in Economic Modeling, Gender Inequalities, Rethinking Macroeconomics