Unpaid Work, Animated

About half of all the time devoted to work in the U.S. is devoted to unpaid work in the home. The Institute for New Economic Thinking has created an adorable animation of some comments I made in an interview with them on this topic a while back.

It’s quite a lot of fun, and basically accurate. Just don’t pay too much attention to the numbers they inserted into my discussion of two families, each with a market income of $50,000–the animation seems to imply that leisure should be assigned a monetary valuation–not something I advocate. Still, the main point comes through just fine: conventional measures provide a misleading picture of living standards.

The animation provides a great introduction to the topic for students, and you can find a more academic version of the basic argument in a short briefing paper I wrote for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on June 11, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, Rethinking Macroeconomics

A Gendered Social Accounting Matrix for South Korea

A social accounting matrix (SAM) is an economy-wide consistent representation of the payments in an economy, linking production, primary factors, and institutions (the latter often split into households, government, and the rest of the world). In the words of Round (2003), “it is a comprehensive, flexible, and dis-aggregated framework which elaborates and articulates the generation of income by activities of production and the distribution and redistribution of income between social and institutional groups.” Most of the time, a SAM refers to the economy of a country for one year. It may be used to describe the structure of an economy and as a data input to economic models, most importantly CGE models. This paper documents a gendered Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) for South Korea for 2014: the steps followed in its construction, the data sources, and what the SAM says about the economic structure of this country (for brevity from now on referred to as Korea), including gender, time use, and the role of households in providing care and other services provided by households. The SAM that is presented is the key data input to a forthcoming analysis of gender and care in Korea’s economy based on GEM Care, a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model.

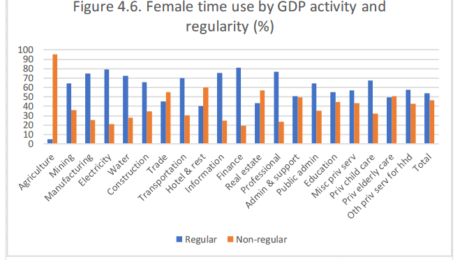

At an aggregate level, the value-added in the GDP economy is roughly 86 percent of the total (with agriculture, industry, services accounting for 2, 33, and 51 percent, respectively) and the non-GDP economy 14 percent. This information may be contrasted with aggregate time shares in terms of which, the non-GDP economy accounts for a much larger share, 40 percent. If leisure also were included, then it would on its own account for 50 percent of total time, 53 percent for men and 47 percent for women. The share of time allocated to household activities are drastically different for men and women, 15 and 57 percent, respectively. For women, non-care household services comprise the largest time using activity by a wide margin, followed by household childcare, trade services, and hotel and restaurant services. For men, manufacturing dominates, followed by trade services, household non-care services, and construction. For agriculture and industry, the lesser educated dominate all activities except electricity for both men and women. For services, the differences across sectors are drastic with some dominated by those with high education and others by those with low. These are few of the many descriptive findings from the gendered SAM developed by the authors.

This paper will be available December 2019.

This blog was authored by Binderiya Byambasuren, Kijong Kim & Hans Lofgren

Policy Analysis in a Macroeconomic Model of Social Reproduction

Since the 1990s, unpaid work and care have garnered increasing academic attention, creating the emerging fields of the economics of unpaid work and the study of “the care economy.” Most of the earlier work was oriented toward microeconomics, focusing on issues such as the household division of labor, subsistence production in developing countries, the substitution between non-market and market goods and services in households, and the role of caring motivations in sectors of the labor market in developed and developing countries. Empirical work paralleled these theoretical efforts. Examples include measuring unpaid work via time-use surveys across the world, estimating the monetary value or opportunity cost of unpaid work, and linking care with the gender–wage gap and gendered job segregation. Macroeconomic models exploring gender and economic development were rare, and even fewer macro studies examined care and unpaid work.

Braunstein et al. (2011) contributed to this literature by embedding unpaid work and care in a structuralist macro model, illustrating how the social structures of production matter for economic outcomes. Braunstein and Tavani (2019) recast a simplified version this model in order to generate policy implications through numerical simulation. The authors go beyond the standard utilization-labor share framing in structuralist models in order to focus on more direct measures of gender inequality and the gender composition of the labor force and of employment. The resulting producer’s equilibrium – which describes the supply side of the model – always features a positive relationship between economic activity and gender wage equality. The goods market equilibrium, or the investment-savings curve, can either be care-led or inequality-led. The model results accommodate a variety of scenarios. A reduction in non-market care time can foster both aggregate demand and gender equality, but under some conditions it is also possible that there are trade-offs between economic activity and gender equality.

This paper will be available in December 2019.

Impact of Investing in Social Care on Employment Generation, Time- and Income-Poverty and Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation for Turkey

CONTRIBUTORS

İpek İlkkaracan, EMEL MEMIS, KIJONG KIM, TOM MASTERSON, and Ajit Zacharias

Feminist economists have long emphasized the recognition, reduction and redistribution of unpaid care work (the so-called 3R strategy) as a primary policy intervention towards closing of the gender economic gaps. Investing in a social care infrastructure is an important component of the 3R strategy. Universal access to quality care services enables reduction of the unpaid work burden through its redistribution from the domestic sphere to the public sphere. Public investment and expenditure, however, is a question of fiscal policy at the helm of macroeconomists and policy-makers who are often gender blind and also adopt the mainstream approach of public expenditure constraint. Several waves of empirical research have examined the allocation of sectoral allocation of public expenditure through macro-micro simulations.

Yet until recently, studies have failed to explore an important outcome of investing in social care from a gender perspective, namely gendered patterns of time allocation. While investing in social care creates jobs for some women, enhances their access to employment and earnings, it also increases the requirements on their time through higher paid work hours. Simultaneous access to services alleviates the unpaid work burden of women with care dependent household members. The net welfare impact for different groups of women and men taking both time- and income-effects into consideration is an empirical question.

The forthcoming paper titled “Impact of Policy Interventions at Reduction and Redistribution of Unpaid Care Work On Employment Generation, Time- And Income-Poverty And Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation For Turkey” by Ilkkaracan, Kim, Masteron, Memis, and Zacharias uses an applied macro-micro simulation policy modelling approach to explore the gendered impact of increased public expenditures on social care service expansion on new employment and income generation, time allocation to paid versus unpaid work, time- and consumption poverty. An increase in social care spending triggers two types of effects at the household and individual level: It generates new jobs improving access of previously non-employed persons (predominantly women) to employment and income generation, but at the expense of increasing paid work time of job recipients. Simultaneously, improved access to childcare services reduces unpaid work time in the households with small children. The authors use a statistically matched data set from the 2015 Time Use Survey (TUS) and the Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) in Turkey to assess the impacts on individual and household well-being, not only in terms of gains in employment and income, but also in terms of potential changes in household production responsibilities and time deficits.

The paper will be available December 2019

The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The case of South Korea

According to the Global Gender Gap Index of the World Economic Forum (2018), South Korea is one of the lowest ranked countries in the world in terms of “Economic Participation and Opportunity” (124th out of 149 countries) as of 2018. The Global Gender Gap Index also shows that South Korea ranks 88th in terms of female labor force participation and 121st in terms of gender wage equality for similar work. The average wages of women in South Korea are on average 36.7% lower than average male wages (as of 2012, own calculations based on World Klems (2014) database). These statistics reflect that there is a significant economic gender gap in South Korea despite the fact that the country is now classified as a high-income economy. Moreover, the underdeveloped care infrastructure and reliance on unpaid care labor of women is posing serious demographic and social sustainability challenges in an aging society.

Existing research on the effects of public spending show a stronger positive effect of public spending in social care and education on female employment as well as total employment compared to public investment in physical infrastructure (Antonopoulos et al., 2010; Ilkkaracan, Kim and Kaya, 2015; Ilkkaracan and Kim, 2018; De Henau et al., 2016; Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou, 2019a). These employment effects have further effects on the economy and the wellbeing of the society, as microeconomic studies across the board attest that a larger share of women’s income compared to that of men’s, is spent to satisfy the needs of the household (Blumberg, 1991; Antonopoulos et al, 2010; Pahl, 2000) and a possible increase in their income leads to increased spending on children’s education and wellbeing (Vogler and Pahl, 1994; Lundeberg et al. 1997; Cappellini, Marilli and Parsons, 2014). Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou (2019a) confirm this finding at the macroeconomic level for the case of the UK. These consequently have further demand and supply side effects on output, productivity and employment (Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou, 2019a; Seguino, 2017).

Oyvat & Onaran (2019) examines the short-run and medium-run impact of public spending in social infrastructure, defined as expenditure in education, childcare, health and social care on aggregate output and employment of men and women for the case of South Korea. They present a gendered Post-Kaleckian theoretical macroeconomic model. The authors estimate the macroeconomic effects of social expenditure using a vector autoregression (VAR) analysis for the period of 1970-2012. The results show that an increase in the public social infrastructure significantly increases the total non-agricultural output and employment in South Korea both the short and medium-run. Moreover, higher social infrastructure expenditure increases female employment more than male employment in the short-run and raises both male and female employment in the medium-run due to increasing aggregate output. Finally, estimates show that the South Korean economy is wage-led and gender equality-led in the short-run, hence overall equality-led, although the effects are economically small in comparison to the strong effects of increases social infrastructure spending, and become insignificant in the medium-run. The results indicate that sustainable equitable development and a substantial increase in employment requires a mix of both labor market and fiscal policies.

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in Gender-Aware Macromodels, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea

The Provision of Elderly Care and the Macroeconomy

The dramatic increase in life expectancy in most developed and developing countries over the last few decades has led to renewed discussions around elderly care policy options, and the debates are expected to intensify as the ratio of elderly to working-age adults continues to rise. According to United Nations, the share of people aged 60 years or over is growing faster than all younger age groups. Older segments of the world population are expected to double by 2050 and to more than triple by 2100. In addition to these demographic shift, contemporary societies are still characterized by prevalent gender inequality. One aspect of gender inequality is the unequal intra-household division of labor, which is particularly important for the analysis of care policies: women still do most of the unpaid care work.

Brun et al (2019) develops an overlapping-generation model to analyze the economic effects of increasing elderly care needs and evaluate different care arrangements, including the prevalence of unpaid care work. They model the demand of care as being complementary to elders’ consumption. This complementarity increases over time, as retired households become older, making the demand for care more inelastic. They analyze how increasing care needs affect key economic aggregates, such as savings, the gendered provision of paid and unpaid care, and the female labor market participation. Finally, they use the model to study the effects of the secular increase in women’s labor supply that took place between the 70s and the 90s on the provision of care, and evaluate alternative social arrangements, e.g. market-based vs publicly provided care, that so far have only partially replaced the unpaid care traditionally provided by women.

The paper will be available December 2019

- Published in Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea

Options for modeling the distributional impact of care policies using a computable general equilibrium (CGE) framework

The importance of public investment and adequate care policies for gender equality has come to the forefront of the policy agenda in recent years. The Sustainable Development Goals framework for the first time explicitly recognizes the unequal distribution of unpaid domestic work and care as main source of gender inequality. Target 5.4, in particular, draws attention to the role that public policies can play in providing infrastructure and social services to both reduce and redistribute domestic work and care., Gender-aware Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models which account for different dimensions of gender inequality in the economy could be adopted to evaluate the gender distributional effects of these policies. Fontana et al. (2019) provide a review of this approach, highlighting the challenges therein as well as the ways forward.

CGE models are representation of the functioning of an entire economy drawing on detailed empirical data, and can be fairly disaggregated in terms of sectors, factors of production and household categories. Existing Gender-Aware CGE (CGGE) have been mostly used to simulate trade related policy changes and fall into two broad categories: those that use a gender-disaggregated approach and those that use a ‘two-systems’ approach. The first set of models disaggregate standard economic variables and categories such as production activities and labour factors to highlight female-intensive sectors. However, unless these disaggregations are accompanied by behavioural rules that reflect the causes of unequal gender patterns, this approach does not generate plausible results

The second set of models are closer to a feminist economics approach as they include unpaid care work and its interaction with the market economy. However existing applications tend to model unpaid care work simply as a constraint to women’s participation in the paid market economy and are limited to comparative statics as opposed to dynamic analysis. There is therefore the need to develop a more nuanced approach that incorporates a range of labour market imperfections as well as dynamic dimensions to better capture the gendered nature of both the market and the non-market economy. Such approach would enable CGE modelers to better explore the distributional implications of alternative care related fiscal policy simulations. Fontana et al. (2019) also review CGE papers that are not gender-aware but incorporate labour market imperfections and dynamic processes that are relevant for gender analysis.

Using insights from these different bodies of CGE literature, they suggest several ways forward for modelling the gender distributional effects of public policies. First, modelers need to disaggregate their data sets not only by gender but also by other socio-economic characteristics to highlight how gender intersects with other sources of disadvantage and to reflect the specific gendered structure of a particular economy. For example, mothers of infants and elderly women face different challenges related to both work and care provision. Second, modelers should consider different wage setting mechanisms and rules of operation of the labour market to better represent the causes of gender discrimination. For example, women in many countries tend to be crowded in a fewer sectors and occupations than men, including into care sectors that offer poor working conditions and pay. Third, modelers need to move beyond modelling unpaid work as simply a constraint to labour market participation and emphasize its role in human capacity development in the long term. To this end, a dynamic approach would be especially useful.

The paper will be available December 2019

- Published in Gender-Aware Macromodels, Rethinking Macroeconomics

Microfinance and the Care Economy

Financial inclusion has been adopted as a developmental strategy with the roll-back of the developmental state under the neoliberal policy regime. As a result, mainstream private finance has utilized microcredit schemes with increasing frequency, even though such schemes initially were touted almost exclusively as tools for gender-empowerment and poverty alleviation. The relatively low rates of default in this sector have attracted an influx of funds from profit-oriented financial institutions, shifting focus from the sustainability of income generation for borrowers to that of the profitability of the lending institution. Given the higher transaction costs associated with small loans and extending outreach to marginal low-income households, this change has undermined the social mission of microfinance to reach the poorest and most neglected households. It appears social priorities are being subordinated to commercial considerations.

The impact of microcredit on both poverty and gender relations has been studied extensively. Yet the implications of microcredit growth for the care-economy, and their repercussions in the wider macro-economy, have received much less analytical attention. This neglect of care-labor provision in particular is surprising given that microfinance originally targeted female workers in rural areas in developing countries with less access to earning opportunities and disproportionate responsibility for care work. The increase in market labor implies a claim on the time of working women. In the absence of social provisioning of care, this claim on the labor time of women likely could lead to a squeeze on the time of rural working women.

We propose a simple two sector post-Keynesian model to integrate the role of demand and care work into the analysis of microfinance. This investigation demonstrates how micro-financed enterprises face a structural constraint on the demand-side from overall macroeconomic conditions. They likewise face a constraint on the supply side from the responsibility for unpaid care work borne by the female beneficiary of microfinance. Paradoxically, microfinance has been espoused as a developmental strategy in precisely the period when the role of the developmental state has been eclipsed and cutbacks in public spending on care provisioning have been prescribed.

Meanwhile, slowdowns in the wider economy lower the demand for the output of the microfinance sector, undermining the viability of these enterprises. The capacity of the microfinance sector to provide the impetus to broader demand growth in the economy therefore is likely to be more limited in the absence of public policies to stimulate demand and investment. The capacity of microfinance to alleviate poverty and lift incomes is thus dependent on conditions in, and linkages with, the wider macroeconomy. A vibrant and stable macroeconomy is the only sustainable basis for a stable microfinance sector.

We also draw attention to some of the complexities of the impact of microfinance for the provision of care. The home-based nature of microenterprise perpetuates the gendered asymmetries of care responsibility within the household. While higher female earnings can alleviate the burden of care by making care work more effective and by enabling the market to substitute for unpaid care, the gendered responsibility for care remains a critical constraint for the female beneficiary of microfinance at the lower income levels and in the context of inadequate social provision of care.

Some clear policy prescriptions emerge from this investigation. Donors and development agencies have been encouraging raising interest rates in order to ensure the viability and profitability of microfinance lenders. However, our model suggests that high interest rates will undermine the scope of microfinance as a path to better and sustainable livelihoods for poor households in rural areas. Higher interest rates in this sector impose a higher burden on the labor-time of the female worker with a consequent squeeze of care-labor or own-labor time.

More significantly, the analysis suggests that microfinance cannot be an effective path to poverty alleviation or gender empowerment, unless it is backed by investment in the social provisioning of care. The success of microfinance as a developmental strategy depends on wider policies that support demand and the social provision of care. Ultimately, there is no substitute for a developmental strategy based on public investment in support of both job creation and social provision of care.

- Published in Research, Rethinking Macroeconomics

(More) Economic Lessons from the Great Recession of 2008

The global financial crisis that began in 2008 resulted in the widespread destruction of jobs. Effects were felt disproportionately among subordinate racial groups and women. While mainstream analyses emphasize regulatory lapses in the financial sector as the principal factor triggering the crisis, the root causes run much deeper. Feminist and stratification economists have enlarged the lens of economists to explore the role that growing inequality played leading up to the crisis. Furthermore, they have made important contributions to the analysis of the macro-level impact of crisis and, with this, to macroeconomic theory and policy (for a detailed discussion, see Seguino 2019).

- Cuts to social spending and economic instability have long-term negative effects on human development and productivity, in part through the gender effects of crisis and austerity.

Women tend to bear greater responsibility than men when it comes to ensuring children receive proper care. They are also among the hardest hit by crises and austerity because they control fewer resources and are more concentrated in low-wage jobs that are insecure and lack benefits (Karamessini & Rubery 2013). Because of women’s predominant responsibility for social reproduction, these effects subsequently are transmitted to children—and the impact can be long-lasting. Neuroscience research over the last 20 years details the mechanisms by which this occurs, but economists have yet to recognize its lessons and significance (Katsnelson 2015; Hair et. al., 2016). Children’s brains are especially susceptible to neurobiological changes, and the effects are harsher on poorer than on wealthier families. A recent study shows, for example, that the brains of children and adolescents with higher family income and more parental education have larger surface areas than their poorer, less-educated peers (Noble et. al., 2015). The regions of the brain most affected are those associated with language, executive functioning, motional control, and memory, negatively impacting the development of children’s cognitive skills. These effects last well into adult life.

This research suggests that economists must redefine their conception and scope of hysteresis, or path dependence. Until now, hysteresis only has been applied to the current labor force, but neuroscience research demonstrates the long-term effects of deprivation on the human brain, especially in children. The economic vulnerability of women and people of color affects children and thus long-run productivity growth. Many macroeconomists have not yet integrated this channel of productivity growth into macro models. Were they to do this, the problem of gender and racial inequality and the shredding of the social safety net would receive the attention they deserve as determinants of long-run growth.

- Targeted public investment can reduce intergroup inequalities and stimulate growth.

Time-use research finds that women are responsible—through gender norms and stereotypes—for a disproportionate share of unpaid work, comprised of care of self and others, and maintenance of the household. Women’s unpaid care burden, crucial for supporting and expanding human capacities of the current and future labor force, inhibits their participation in paid work. Women’s limited access to income, as a result, redounds negatively on children, given evidence of their greater (than male) responsibility for children’s well-being (Doss 2013). This points to the centrality of public investment to reduce women’s care burden.

A number of scholars have explored the gender effects of physical infrastructure investment (in, for example, sanitation, roads, and electricity) [Agénor et. al., 2010]. They find that such investments reduce women’s care burden, particularly in low-income countries where women spend a significant amount of time on unpaid work such as fetching water and firewood. Because these investments help to reduce time poverty (due to time spent on unpaid work), they expand women’s ability to take on paid work, which in turn increases their bargaining power in the household to direct resources to children, promoting long-run productivity growth as a result.

Similarly, physical infrastructure investments can be used to address racial inequalities. In developed countries, for example, residential segregation combines with infrastructure inequality, as the recent case of contaminated water in Flint, Michigan has shown. In addition, lead, asbestos, and chemical toxins worsen the health of children in those communities with life-long effects on their cognitive development and thus productivity. These conditions represent a key aspect of intergroup inequality. But they also have macroeconomic implications as a result of the effect on labor productivity and thus growth.

- Social infrastructure spending promotes gender equality, productivity growth, and creates fiscal space.

Keynesian economists emphasize the effect of government spending on aggregate demand and growth. Feminist heterodox economists take this further, underscoring the importance of strategically targeting government spending to achieve a broader set of goals, including gender and racial equality, and productivity growth. They thus contribute to an understanding of both the demand- and supply-side effects of government spending.

Targeting government spending to social infrastructure (which includes such sectors as childcare, education, and health) expands human capacities. Qualities that make human beings economically effective, such as emotional maturity, patience, self-confidence, and the ability to work in teams have a public goods quality with positive spillover effects on economy-wide productivity (Braunstein, et. al. 2011). Because care work (both paid and unpaid) is a highly gendered activity, with women providing the bulk of the labor, social infrastructure investment can improve women’s access to paid work.

In a recent study, Dehenau & Himmelweit (2016) assess the impact of a public investment of 2% of GDP to either the care or construction sector. They find that in the short-term, government spending targeted to the care sector reduces women’s unpaid work and creates more paid jobs than spending in the construction sector. In the medium term, wages in care sector rise. Given that this sector is one that is female-dominated in employment, the gender wage gap narrows. In the long term, productivity rises due to improvements in human capacities. Antonopoulos et. al. (2011) obtain similar results, with the added outcome that in the US, social service jobs have stronger positive effects on disadvantaged and poor workers (that is, women and people of color).

This spending also has the salutary effect of creating fiscal space over the medium run. As a result, feminist research highlights that it is useful substitute the term social spending with social infrastructure spending, because targeted spending on social infrastructure produces a stream of financial returns into the future due to impact on productivity and incomes. As such, using fiscal policy to promote gender and racial equality creates fiscal space. It is time for economists to begin thinking of such spending as an investment rather than merely as a form of discretionary spending, or a target for cuts during hard economic times.

Macroeconomists, and for that matter economists and policymakers more generally, can benefit from a greater focus on intergroup inequalities by race and gender. This is because macro policy has differential race, gender and class effects. Policies (and models) that fail to incorporate the dynamic effects of intergroup inequality can lead to unintended and harmful outcomes. And intergroup inequality in turn affects important macroeconomic outcomes, including employment and productivity growth.

On the policy side, while explicitly targeted gender and race policies may be helpful, it should be noted that policies that may appear to be gender and race neutral can nevertheless close gaps. For example, sector-specific fiscal spending, full-employment policies, capital controls that reduce volatility, and labor market regulations to address insecure work may benefit all workers but be particularly effective in improving the lives of people of color and women, all with simultaneous economy wide-benefits on productivity growth.

The bottom line:

For some macroeconomists, gender and racial inequality and the impact of macro policies on children may appear to be outside their realm of focus. They are encouraged to resist the temptation to focus their sights too narrowly. Just as class dynamics have macroeconomic implications as demonstrated by Kaleckian economists, so too do gender and race. The effects are not only on the demand side, but also on the supply side of the economy with important implications for fiscal policies that that ensure a path to equity-led growth.

This blog was authored by Stephanie Seguino.

REFERENCES

Agénor, P.-R, Canuto, O., & da Silva, L. P. (2010). On Gender and Growth: The Role of Intergenerational Health Externalities and Women’s Occupational Constraints. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 5492.

Antonopoulos, R., Masterson, T., & Zacharias, A. (2011). Investing in Care: A Strategy for Effective and Equitable Job Creation. In Antonopoulos, A. (ed), Gender Perspectives and Gender Impacts of the Global Economic Crisis, London: Routledge, pp. 47-72.

Braunstein, E., van Staveren, I., & Tavani, D. (2011). Embedding Care and Unpaid Work in Macroeconomic Modeling: A Structuralist Approach. Feminist Economics 17(4), 5-31.

De Henau, J. & Himmelweit, S. (2016). Developing a Macro-Micro Model for Analysis of Gender Impacts of Public Policy. Paper presented at Gender and Macroeconomics: Current State of Research and Future Directions, Levy Economics Institute, Bard College, New York City, March 9, 2016.

Doss, C. (2013): Bargaining and Resource Allocation in Developing Countries. World Bank Research Observer 28(1): 52–78.

Hair, N., J. Hanson, B. Wolfe, and S. Pollak. (2105). “Association of Child Poverty, Brain Development, and Academic Achievement. JAMA Pediatrics 169(9), 822-829.

Karamessini, M. & Rubery, J. (2013). Women and Austerity: The Economic Crisis and the Future for Gender Equality, Routledge IAFFE Advances in Feminist Economics.

Katsnelson, A. (2015). News Feature: The Neuroscience of Poverty. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112(51), 15530-15532.

Noble, K., S. Houston, N. Brito, H. Bartsch, E. Kan, J. Kuperman, N. Akshoomoff, D. Amaral, C. Bloss, O. Libiger, N. Schork, S. Murray, B. Casey, L. Chang, T. Ernst, J. Frazier, J. Gruen, D. Kennedy, P. Van Zijl, S. Mostoofsky, W. Kaufmann, T. Kenet, A. Dale, T. Jernigan, & E. Sowell. (2015). Family Income, Parental Education and Brain Structure in Children and Adolescents. Nature Neuroscience, 18, 773–778.

Seguino, S. 2019 (forthcoming). Feminist and Stratification Theories: Lessons from the Crisis and Their Relevance for Post-Keynesian Theory. European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies.

- Published in Research, Rethinking Macroeconomics

Gendering Fiscal Policy

The importance of public physical infrastructure in stimulating productivity and economic performance is embraced by most economists. However, there is less awareness that public spending in health, social care, education, and childcare should be considered as investment in social infrastructure. We therefore develop a feminist post-Keynesian/post-Kaleckian demand-led growth model to elucidate the impact of gender equality and public spending in these social sectors within a theoretical framework. In particular, we use the model to analyse the effects of fiscal policies and decreasing the gender wage-gaps on GDP, productivity (GDP per employee), and employment of men and women in both the short run and long run.

Our analysis challenges conventional thinking about the impact of public spending in health, social care, education, and childcare. Day-to-day spending in these sectors (e.g. wages of teachers, nurses, or social care workers) is considered as “current spending” rather than as investment in our national accounts. However, public spending in these social sectors have long-term benefits to society, yielding substantial productivity impacts in all other sectors of the economy by increasing people’s skills, health, and innovative capacities.

Crucially, these social sectors improve gender equality and reverse one of the most persistent dimensions of inequality in our societies; they provide crucial services which are otherwise provided by the unpaid invisible domestic labour of women. Public supply of these services helps women to participate in social and economic life more equally. This in turn further increases productivity by unleashing the hidden potential of women. Moreover, in the current gendered, occupationally segregated labour markets, these sectors employ predominantly women. More public social spending consequently leads to closing the gender-gap in employment. As a result, these expenditures are labelled as “purple public investment” by feminist economists (İlkkaracan, 2013).

Recognizing the vast amount and importance of time women spend on unpaid care at the household, which is not accounted for in the standard national accounts and measures such as GDP, is crucial for designing policies to increase gender equality. A fiscal policy stance, which aims to publicly provide the necessary social services, would socialize part of these activities and radically decrease the amount of unpaid private care. For instance. universal free childcare and nurseries open for sufficiently long hours benefit both mothers and fathers by giving them an equal chance to balance work with other social, cultural, and political aspects of their lives. Meanwhile, provision of these resources also benefits society at large by decreasing inequality between children from different backgrounds and improving the creative capacity of children. Of course, there always will be the need and desire for care provided by family members for children or the elderly in the domestic private sphere. Nevertheless, regulations such as parental leave for both mothers and fathers in addition to working time arrangements that facilitate combining care and work for both men and women should help to ensure that time for caring can be equally shared between men and women.

What, then, does this imply for fiscal policy and the setting of the budget deficit or public debt targets? Fiscal policy should be focused on the needs and well-being of society rather than aiming at a singular target for the sake of the deficit. The mainstream approach of limiting the governments’ fiscal space is based on a mistaken household analogy that the public sector should balance its budget just like any household has narrowed down the political space. Within this narrow space, the idea of a fiscal credibility rule suggests that spending on public investment can be funded by borrowing, while day-to-day spending is financed by tax revenues. Even under this limited fiscal space, the idea of defining public spending in universal health, social care, education, and childcare as investment in valuable social infrastructure would extend the scope so that fiscal policy could be financed by borrowing as well as by raising tax revenues. Furthermore, mainstream policies consider even public spending financed by increased taxation of income, wealth, and corporate profits as undesirable based on the myth that it would lead to low private investment and productivity in the long term. But this assessment is rather static as it totally ignores the positive impact of these policies on macroeconomic demand, and in turn on productivity and private investment.

Our macroeconomic model can form the basis for the empirical analysis of gender equality and fiscal policy on growth, productivity, and budget balance while also serving as a tool for policy analysis and gender-responsive budgeting. In particular, the model allows policy makers to analyse the impact of fiscal policy-based employment increases in health, social care, education, and childcare along with an upward convergence in wages in these public sector jobs with closing gender pay gaps. The model also anticipates public investment in social infrastructure to reduce women’s unpaid domestic care work, while increasing their labour supply and enabling them to spend more time in paid work. Aggregate demand is expected to be stimulated both in the short- and long-run via strong multiplier and productivity effects of public investment in social infrastructure. Higher employment and closing of the gender pay gaps via higher wages for women in the public social infrastructure sector is also expected to stimulate household consumption with positive demand effects for the economy. In the long run, government spending as well as higher wages of women are expected to increase productivity. Both the demand effects in the short-run and the long-term productivity effects, which further increase profitability, are expected to stimulate private investment as well.

Given the labour-intensive and domestic demand-oriented nature of social infrastructure and occupational segregation, such investment is expected to lead to very strong increases in the employment rates of women as well as to the creation of a substantial amount of jobs for men in all sectors of the economy due to spill-over effects of demand from the social sector to the rest of the economy. This policy thereby also contributes to closing the gender gaps in employment. Due to sectoral and occupational segregation, public spending in social infrastructure is expected to create more employment for women compared to physical infrastructure. According to empirical research based on input-output tables (Antonopoulos et al., 2010; İlkkaracan et al., 2015; De Henau et al., 2016; İlkkaracan and Kim, 2018), public investment in physical infrastructure creates fewer jobs in total, and most new jobs are predominantly male jobs. However, this research does not consider the long term effects on productivity. An empirical analysis of our model for a specific economy can further shed light on the gendered policy implications.

The expansionary effects of fiscal policy lead to higher tax revenues in the economy; hence, fiscal policy partially finances itself. The model can be used to simulate further policy-mix scenarios including increases in tax rates on capital or labour to ensure that public social infrastructure investment and closing gender gaps in these sectors can fully be financed. Progressive taxation, which improves after-tax equality in terms of income and gender, is also important in the context of public spending on non means-tested services such as universal health and social care, education and childcare. A higher tax rate on higher incomes is a way of those who can afford contributing more towards universally provided public services.

References

Antonopoulos, R., K. Kim, T. Masterson and A. Zacharias (2010) ‘Investing in Care: A Strategy for Effective and Equitable Job Creation.’ Working Paper No.610. Levy Economics Institute

De Henau, J., Himmelweit, S. Łapniewska, Z. and Perrons, D., (2016) Investing in the Care Economy: A gender analysis of employment stimulus in seven OECD countries. Report by the UK Women’s Budget Group for the International Trade Union Confederation, Brussels. https://wbg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/De_Henau_Perrons_WBG_CareEconomy_ITUC_briefing_final.pdf

İlkkaracan, İ., 2013 ‘The Purple Economy: A Call for a New Economic Order Beyond the Green’, in U. Röhr and C. van Heemstra (eds), Sustainable Economy and Green Growth: Who Cares? LIFE e.V./German Federal Ministry for the Environment, 32–7.

İlkkaracan, İ., and Kim, K. 2019. The employment generation impact of meeting SDG targets in early childhood care, education, health and long-term care in 45 countries, Geneva, ILO, forthcoming

İlkkaracan, İ., Kim, K. and Kaya, T. (2015). The Impact of Public Investment in Social Care Services on Employment, Gender Equality, and Poverty: The Turkish Case. Research Project Report, Istanbul Technical University Women’s Studies Center in Science, Engineering and Technology and the Levy Economics Institute, in partnership with ILO and UNDP Turkey, and the UNDP and UN Women Regional Offices for Europe and Central Asia

- Published in Research, Rethinking Macroeconomics, Uncategorized