Caring For the Future: How Public Spending Makes a Difference

During the first week of June, the Center for Transnational Migration and Social Inclusion at Seoul University and the Care Work and the Economic Project at American University will host a conference to discuss the role of care work and the care economy in a post-pandemic future. National and international scholars will take this opportunity to discuss the role of public spending in gender equality, and its relation to economic growth.

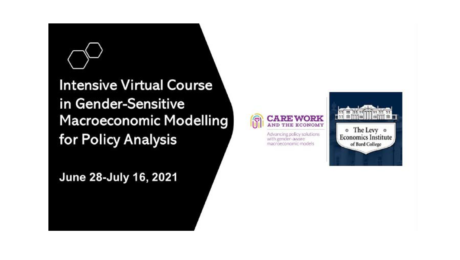

In their paper “The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The Case of South Korea”, Oyvat and Onaran (2020) use a feminist post-Kaleckian model to estimate the impact of an increase in the total social infrastructure expenditure, wages, and closing the gender pay gap on output and employment. They find that an increase in South Korea’s public social expenditure has a positive cumulative effect on output, as well as on female and male employment (hours of work) in the non-agricultural sector, both in the short and medium terms (figure below).

(Oyvat and Onaran, 2020, p.29).

Pierre-Richard Agenor and Madina Agenor in “Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation and Economic Growth” (2019) develop a two-period, gender-based overlapping generations model (OLG) with public capital to explore the implication of public infrastructure on women’s time allocation and growth. They find that government provision of infrastructure can induce women to reallocate time away from home production activities and toward market work, as well as have a significant impact on health and education for both men and women, positively affecting their productivity.

Finally, Ignacio Gonzalez, Bong Sun Seo and Maria S. Floro use a macroeconomic overlapping generations model (OLG) to incorporate long-term care and the provision of gender-based unpaid care in their paper “Norms, Gender Wage Gap and Long-Term Care” (2020). They consider the persistence of traditional gender norms as an explanation to the perpetuation of unequal distribution of care work across genders. The unfair division of unpaid care work increases the gender wage gap and creates gender-unequal equilibrium outcomes. They examine how investment in quality care services, care relevant infrastructure, and in encouragement of gender-egalitarian norms can play a role in reducing and redistributing the load of unpaid care work.

This blog was contributed by Carla (Anai) Herrera, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

Sources:

Agenor and Agenor (2019). “Access to infrastructure, women’s time allocation and economic growth” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. DOI: 10.17606/8m8y-mp65

Gonzalez Garcia, Seo, and Floro (2020). “Norms, gender wage gap and long-term care” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/7E2K-1508.

Oyvat, C. and O. Onaran (2020). “ The effect of public social infrastructure and gender equality on output and employment: The case of South Korea “ Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. DOI: 10.17606/fhq4-c294

- Published in Uncategorized

Fellows Reflect on Intensive Course in Gender-Aware Macro Modeling

Last month, the Care Work and the Economy project partnered with the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College to host a three-week Intensive Course in Gender-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling taught in three time zones. The course aimed to engage our internationally diverse pool of Fellows to enhance capacity building in research and teaching of gender-sensitive economic analysis, focusing on care and macroeconomic policy aspects.

The course was built on four pillars:

1. Understanding and measuring the care economy

2. Adapting social accounting matrices to account for paid and unpaid care activities.

3. The use of information from time-use surveys on unpaid care activities with other relevant sources and information such as national income accounts, labor force surveys, and household or special surveys

4. Performing policy-relevant economic analyses that take systematic account of the interlinkages between care, macroeconomic processes, and distribution.

With 72 Fellows from 22 countries, including Colombia, Ghana, Mexico, Mongolia (to name a few), discussions around course material were perspective-rich and interdisciplinary. Reflecting on the course, many Fellows expressed the desire to integrate the teachings of the intensive course into their research agendas or current positions:

“I am delighted [to be a part of] a fantastic cohort and faculty who want to, and actually do, think critically about [macroeconomic] modelling in a gender-aware or feminist context…I am excited about the possibility of applying what I have learned to Cuban and Latin American contexts, [and] I would like to delve deeper into the Levy Micro-Macro model to analyze gender differences [in] the Ecuadorian context using time-use data.” — Anamary Maqueira Linares, Ph.D. student at University of Massachusetts, Amherst from Ecuador

“Inspired by Professor Folbre’s [lecture], I would like to conduct research using updated time-use surveys (such as the Mexican case)…I would like to explore the differences between time-use patterns in rural areas versus urban ones in Mexico and compare data from 2014 to the recent time-use survey in 2019. I am also organizing a workshop with the Mexican Statistics Agency [to explore] how the Mexican database was built (contrasted with other countries’ surveys) and promote its use among Mexican graduate students and policymakers.” — Dulce Guevara Lopez, consultant at the Mexican Centre for Innovation in Solar Energy

“It was interesting to learn how care and social reproduction interact with gender inequality in the labour market to determine economic growth/development. I think that [this would be] a good research perspective in the African context to see how household commodities and care-time interact with the gender segmented labour market to determine economic growth.” — Dr. Mamaye Thiongane, research associate at the Regional Consortium for Research in Generational Economy (CREG) and lecturer in economics at the Public Economics Laboratory (LEP)

“The discussions around the care diamond gave me a framework to think through the situation of community health workers in India. I plan to apply the Levy model and the care dependency ratio to the time-use survey for India. The course also helped me gather feminist insights to incorporate into the macro course that I teach at university.” — Dr. Anjana Thampi, assistant professor of economics at O. P. Jindal Global University, India

“The course was a fantastic deep-dive into the theory and practice of [macroeconomic] modelling for care, and sparked new ideas for my Ph.D. research. At a time when distances feel huge, the conversations and connections with lecturers and colleagues created a sense of closeness; something I will treasure this summer.” — Maria Sandoval Guzman, Ph.D. candidate in Economics at Curtin University in Australia, and scholar at the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre and the Women in Social Economic Research Cluster

This course has strengthened the network of researchers around the world dedicated to gender equality and proper care valuation; thank you to all Fellows, Instructors, and Facilitators for their contributions. To learn more about the course, instructors, and Fellows, click here.

This blog was written by Lucie Prewitt, research and communications assistant for the Care Work and the Economy Project.

CWE-GAM Scholars Leading Two Panels During 2021 IAFFE Annual Conference

This week, the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) will hold its Annual Conference: “Sustaining Life: Challenges of Multidimensional Crises” starting on Tuesday, June 22nd, and concluding Friday, June 25th. This conference will provide a forum for scholars to discuss feminist approaches to constructing “inclusive and resilient economic and political systems and [sustainting] our environment” in the context and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Care Work and the Economy Project will be leading two panel discussions on Wednesday, June 23rd and Thursday, June 24th: “Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” chaired by Elizabeth King and Ito Peng, and “Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” chaired by Young Ock Kim. In the discussions, CWE-GAM researchers will present gender-aware macroeconomic models, data collected from unique surveys of care providers and families, and microeconomic simulations used to better understand care work and the economy.

“Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” is scheduled for Wednesday, June 23rd from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time) and will contribute to ongoing efforts to “illustrate the intersectionality of care provisioning, economic growth, and distribution.” With an increasing need for care due to the rapid decline in fertility rates and aging population, South Korea offers a unique context to introduce models and analyze surveys given to households, child and eldercare workers.

There will be four papers presented in this panel:

“The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The Case of South Korea” by Cem Oyvat and Ozlem Onaran “introduces a post-Kaleckian feminist model to analyze the effects of public social expenditure and gender gaps on output and employment building on Onaran, Oyvat, and Fotopoulou (2019), and extending it with an endogenous labor supply and wage bargaining model.”

“The Quality of Life of Family Caregivers: Psychic, Physical, and Economic Costs of Eldercare in South Korea” by Jiweon Jun, Elizabeth King, and Catherine Hensly “examines the psychic, physical, and opportunity costs of caregiving within the family using data from a special-purpose national survey of 501 households conducted in Seoul in 2018.”

“Quality of Care, Commitment Level, and Working Conditions: Understanding the Care Workers’ Perspective” by Shirin Arslan, Maria Floro, Arnob Alam, Eunhye Kang, and Seung-Eun Cha uses “the 2018 Care Work Economy (CWE-GAM) survey data collected from 600 child and eldercare workers in South Korea [to] analyze patterns of commitment levels among [paid carers] in various settings such as private and public institutions as well as in homes of recipients by conducting tobit regressions and entropy econometrics for robustness checks.”

“Impacts of COVID-19 on Work-Family Balance in South Korea: Empirical Findings and Policy Implications” by Ito Peng and Jiweon Jun examines COVID-19’s unequal impact between men and women in South Korea using data from a survey distributed to “1,252 households with at least one child aged between 0 and 12 in June 2020 to find out how the first 2-month social distancing measure had affected their work, childcare arrangements, and their wellbeing.”

“Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” is scheduled for Thursday, June 24th from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time), which will share the results of gender-aware applied modelings and micro simulations for South Korea. The panel will discuss which fiscal policies are likely to be the most effective at reducing gender gaps in paid employment and which forms of public investment best contribute to reducing and redistributing unpaid work between genders and socio-economic groups.

There will be three papers presented in this panel:

“Child and Elderly Care in South Korea: Policy Analysis with a Gendered, Care-Focused Computable General Equilibrium Model” by Martin Cicowiez and Hans Lofgren presents the first care-focused and gendered model in the computable general equilibrium literature for Korea that “is built around a social accounting matrix (SAM) that covers non-GDP household services, singles out sectors for child and elderly care, and disaggregates households on the basis on care needs.”

“Care Support Ratios in Korea and the US” by Gretchen S. Donehower and Bongoh Kye takes a holistic view of care by including both paid and unpaid care for all age ranges and “create[s] [care support ratios] to understand the current care market and whether it is sustainable in the future…in two aging populations- Korea and the United States.”

“Towards a Caring and Gender-Equal Economy in South Korea: How much does the regulation of labor market working hours matter?” by Ipek Ilkkaracan and Emel Memis “use[s] a unique time-use survey on care arrangements by couples with small children in order to explore the potential of [the] reduction of full-time market work hours towards [the] narrowing of the gender gaps in paid and unpaid work.”

To learn more about the panels presented by CWE-GAM researchers and the IAFFE conference, please visit the IAFFE 2021 Annual Conference homepage and program.

This blog was contributed by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

50 Researchers Come Together for 2019 Annual Meeting

2019 Care Work and the Economy Annual Meeting in Glasgow, Scotland

The Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) held its 2nd Annual Meeting in Glasgow, Scotland on June 30-July 2, 2019. The network of 50 researchers and stakeholders convened to discuss the project’s progress since its 2018 Annual Meeting in Berlin. The Co-Principal Investigators Maria Floro and Elizabeth King commenced the meeting by introducing the different working groups of the project and highlighting some of the project’s outputs so far. Program Officers from the sponsors The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and Open Society Foundations related their support for research on care work and its link to engendering policy and advocacy work. Find the full meeting agenda here and a summary of the meeting below.

The Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) held its 2nd Annual Meeting in Glasgow, Scotland on June 30-July 2, 2019. The network of 50 researchers and stakeholders convened to discuss the project’s progress since its 2018 Annual Meeting in Berlin. The Co-Principal Investigators Maria Floro and Elizabeth King commenced the meeting by introducing the different working groups of the project and highlighting some of the project’s outputs so far. Program Officers from the sponsors The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation and Open Society Foundations related their support for research on care work and its link to engendering policy and advocacy work. Find the full meeting agenda here and a summary of the meeting below.

Rethinking Macroeconomics (Working Group 1)

The first day of the conference was devoted to discussing theoretical papers incorporating care into macroeconomic frameworks. Elissa Braunstein, Professor of Economics at Colorado State University, recapped the papers produced in the first year:

- “Microfinance and the Care Economy” by Ramaa Vasudevan and Srinivas Raghavendran

- “Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Growth” by Pierre-Richard Agénor and Madina Agénor

- “Gendering Macroeconomic Analysis and Development Policy: A Theoretical Model for Gender Equitable Development” by Özlem Onaran, Cem Oyvat, and Eurydice Fotopoulou

- “Endogenous Growth, Population Dynamics, and Returns to Scale: Long-Run Macroeconomics when Demography Matters” by James Heintz and Nancy Folbre

- “Estimating the Role of Social Reproduction in Economic Growth” by Elissa Braunstein, Stephanie Seguino, and Levi Altringer

These 5 papers can be accessed in full here.

Five additional papers were presented at the meeting followed by active discussion and feedback:

- “The Unequal Distribution of Care Work and the Macroeconomy” by Ignacio Garcia González, Lídia Brun, Maria Floro, and Bong Sun Seo

- “Long-Term Care and Family Power Dynamics” by Ray Miller and Neha Bairoliya

- “Policy Analysis in a Macroeconomic Model of Social Reproduction” by Elissa Braunstein and Daniele Tavani

- “Impact of Policy Interventions at Reduction and Redistribution of Unpaid Care Work on Employment Generation, Time- And Income-Poverty and Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation For Turkey” by Ipek Ilkkaracan, Kijong Kim, Tom Masterson, Emel Memis, and Ajit Zacharias

- “The Effect of Gender Equality and Fiscal Policy on Growth and Employment: The Case of South Korea” by Cem Oyvat and Özlem Onaran

After each paper discussion, Braunstein led a general discussion on the persistent gaps in gender-aware macro models and the critical aspects of care incorporated in them. The attendees raised several dimensions of care including quality, its effect on labor productivity, the role of technology, its intersection with migration, and the distinction between publicly and privately provided care services. The importance of making underlying assumptions and modeling decisions transparent and the relevance of such models in other settings and institutional environments were discussed as well.

Understanding and Valuing Care (Working Group 2)

Group 2 started the second day of the meeting with the presentation of their work on accounting for and understanding care work in South Korea. Jooyeoun Suh presented the methodologies for measuring the paid and unpaid care sectors using various national datasets. Gretchen Donehower presented the methodology for projecting care demand and supply to 2030.

To understand the nature of care work in South Korea, Ito Peng gave an overview of care policies and the status of care workers. Eunhye Kang presented findings on the various care arrangements and the nature of caregiving activities for young children and frail elderly using the newly collected Care Work Family Survey data. The next presentation focused on measuring and understanding the strain of caregiving. Ito Peng introduced a multidimensional measure of caregiving strain. Hyuna Moon shared findings from her qualitative fieldwork on unpaid caregivers’ eldercare responsibilities and work burdens. Seung-Eun Cha showed how the unpaid caregivers’ desired and actual time spent on eldercare differed using the Care Work Family Survey.

Following the presentations, the meeting attendees engaged in discussion on how to define paid care work, the importance of distinguishing between public and private care services, and how much of the experience in and lessons from South Korea are generalizable to other countries.

Gender Aware Applied Modelling (Working Group 3)

Group 3 provided an update of the Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models incorporating care. Marzia Fontana and Carmen Estrades provided a literature review of applied models of gender-equitable macroeconomic policies and noted the potential contribution of CGE models. Hans Lofgren presented a gendered Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) for a CGE model in South Korea and suggested relevant policy simulations. A lively discussion ensued regarding how best to incorporate in the model social norms, migration, the relationship between care and human capital formation, and the public and private forms of care provision. Participants also shared ideas on how to present the CGE model in a convincing way to Korean policymakers such as engaging with Korean CGE modelers, validating the SAM with Statistics Korea and Korean researchers, and conducting robustness checks.

Roundtable Discussions

Elizabeth King moderated a roundtable discussion on the current and future demand for care and its implications for the economy. The issue of care is front and center due to rapidly changing demographics around the world; at the same time the types of care demand need to be carefully considered as they can differ across countries. Distinguished panelists discussed the different demands for care, which can vary by development stage, the importance of good data on care, and the search for an optimal mix or combination of family, market and public care provision.

Shahra Razavi moderated a second roundtable discussion that brought together a diverse group of academic researchers, policymakers and activists in Scotland and South Korea. The panel discussed the current situations of public care provisioning, the working conditions of paid and unpaid caregivers, and the challenges that stakeholders face in both countries. While Scotland and South Korea have taken formal measures to increase the role of government in care provision and to recognize the value of unpaid care at home, the implementation of these measures can be challenging due to social norms, rural-urban divide and problems in recruiting and retaining paid care work force. Research plays an important role in promoting effective, gender-aware care policies and in pushing the agenda for equitable, quality care provisioning.

Application to Other Countries

Participants engaged in group discussions on the possibility of adapting the Care Work and the Economy project in different parts of the world. In Latin America, Colombia and Uruguay were identified as possible countries for adaptation; both countries are at early stages of care policy implementation and have strong research capacity, with interest from advocacy groups. In Africa, the group highlighted the importance of framing the relevance of care within the context of achieving a demographic dividend. There is also need to make a strong case as to why governments should invest in care provisioning; further empirical work is required in order to fully understand the current care delivery system and varied forms of care arrangements. Two countries that can be considered for developing a care and the economy project are Senegal and Uganda. In Asia, Thailand and Mongolia are identified as potential countries for adaptation with both countries heavily relying on families for caregiving and lacking government support for care services.

Going Forward

Representatives of the Project’s three working groups expressed their commitment to collaborate and work together in moving forward with producing the final outputs of the project. Group 1 announced their plans to publish special issues of an academic journal to showcase their papers. In South Korea, Group 2 will host a conference inviting policymakers, advocacy groups and academia in October 2019 and to host a policy dialogue conference with Korean government officials and a training workshop for advocacy groups in 2020. Group 3 will move forward in revising the gendered Social Accounting Matrix based on comments raised at the meeting and in conducting simulations on policies of interest in collaboration with Group 2. Other key recommendations from the meeting participants included improving communication and exchange between working groups so as to produce a coherent set of outputs (papers), clarifying the generalizability of the Korean case study to other countries, and using different communication strategies in order to disseminate the findings.

- Published in Uncategorized

Gendering Fiscal Policy

The importance of public physical infrastructure in stimulating productivity and economic performance is embraced by most economists. However, there is less awareness that public spending in health, social care, education, and childcare should be considered as investment in social infrastructure. We therefore develop a feminist post-Keynesian/post-Kaleckian demand-led growth model to elucidate the impact of gender equality and public spending in these social sectors within a theoretical framework. In particular, we use the model to analyse the effects of fiscal policies and decreasing the gender wage-gaps on GDP, productivity (GDP per employee), and employment of men and women in both the short run and long run.

Our analysis challenges conventional thinking about the impact of public spending in health, social care, education, and childcare. Day-to-day spending in these sectors (e.g. wages of teachers, nurses, or social care workers) is considered as “current spending” rather than as investment in our national accounts. However, public spending in these social sectors have long-term benefits to society, yielding substantial productivity impacts in all other sectors of the economy by increasing people’s skills, health, and innovative capacities.

Crucially, these social sectors improve gender equality and reverse one of the most persistent dimensions of inequality in our societies; they provide crucial services which are otherwise provided by the unpaid invisible domestic labour of women. Public supply of these services helps women to participate in social and economic life more equally. This in turn further increases productivity by unleashing the hidden potential of women. Moreover, in the current gendered, occupationally segregated labour markets, these sectors employ predominantly women. More public social spending consequently leads to closing the gender-gap in employment. As a result, these expenditures are labelled as “purple public investment” by feminist economists (İlkkaracan, 2013).

Recognizing the vast amount and importance of time women spend on unpaid care at the household, which is not accounted for in the standard national accounts and measures such as GDP, is crucial for designing policies to increase gender equality. A fiscal policy stance, which aims to publicly provide the necessary social services, would socialize part of these activities and radically decrease the amount of unpaid private care. For instance. universal free childcare and nurseries open for sufficiently long hours benefit both mothers and fathers by giving them an equal chance to balance work with other social, cultural, and political aspects of their lives. Meanwhile, provision of these resources also benefits society at large by decreasing inequality between children from different backgrounds and improving the creative capacity of children. Of course, there always will be the need and desire for care provided by family members for children or the elderly in the domestic private sphere. Nevertheless, regulations such as parental leave for both mothers and fathers in addition to working time arrangements that facilitate combining care and work for both men and women should help to ensure that time for caring can be equally shared between men and women.

What, then, does this imply for fiscal policy and the setting of the budget deficit or public debt targets? Fiscal policy should be focused on the needs and well-being of society rather than aiming at a singular target for the sake of the deficit. The mainstream approach of limiting the governments’ fiscal space is based on a mistaken household analogy that the public sector should balance its budget just like any household has narrowed down the political space. Within this narrow space, the idea of a fiscal credibility rule suggests that spending on public investment can be funded by borrowing, while day-to-day spending is financed by tax revenues. Even under this limited fiscal space, the idea of defining public spending in universal health, social care, education, and childcare as investment in valuable social infrastructure would extend the scope so that fiscal policy could be financed by borrowing as well as by raising tax revenues. Furthermore, mainstream policies consider even public spending financed by increased taxation of income, wealth, and corporate profits as undesirable based on the myth that it would lead to low private investment and productivity in the long term. But this assessment is rather static as it totally ignores the positive impact of these policies on macroeconomic demand, and in turn on productivity and private investment.

Our macroeconomic model can form the basis for the empirical analysis of gender equality and fiscal policy on growth, productivity, and budget balance while also serving as a tool for policy analysis and gender-responsive budgeting. In particular, the model allows policy makers to analyse the impact of fiscal policy-based employment increases in health, social care, education, and childcare along with an upward convergence in wages in these public sector jobs with closing gender pay gaps. The model also anticipates public investment in social infrastructure to reduce women’s unpaid domestic care work, while increasing their labour supply and enabling them to spend more time in paid work. Aggregate demand is expected to be stimulated both in the short- and long-run via strong multiplier and productivity effects of public investment in social infrastructure. Higher employment and closing of the gender pay gaps via higher wages for women in the public social infrastructure sector is also expected to stimulate household consumption with positive demand effects for the economy. In the long run, government spending as well as higher wages of women are expected to increase productivity. Both the demand effects in the short-run and the long-term productivity effects, which further increase profitability, are expected to stimulate private investment as well.

Given the labour-intensive and domestic demand-oriented nature of social infrastructure and occupational segregation, such investment is expected to lead to very strong increases in the employment rates of women as well as to the creation of a substantial amount of jobs for men in all sectors of the economy due to spill-over effects of demand from the social sector to the rest of the economy. This policy thereby also contributes to closing the gender gaps in employment. Due to sectoral and occupational segregation, public spending in social infrastructure is expected to create more employment for women compared to physical infrastructure. According to empirical research based on input-output tables (Antonopoulos et al., 2010; İlkkaracan et al., 2015; De Henau et al., 2016; İlkkaracan and Kim, 2018), public investment in physical infrastructure creates fewer jobs in total, and most new jobs are predominantly male jobs. However, this research does not consider the long term effects on productivity. An empirical analysis of our model for a specific economy can further shed light on the gendered policy implications.

The expansionary effects of fiscal policy lead to higher tax revenues in the economy; hence, fiscal policy partially finances itself. The model can be used to simulate further policy-mix scenarios including increases in tax rates on capital or labour to ensure that public social infrastructure investment and closing gender gaps in these sectors can fully be financed. Progressive taxation, which improves after-tax equality in terms of income and gender, is also important in the context of public spending on non means-tested services such as universal health and social care, education and childcare. A higher tax rate on higher incomes is a way of those who can afford contributing more towards universally provided public services.

References

Antonopoulos, R., K. Kim, T. Masterson and A. Zacharias (2010) ‘Investing in Care: A Strategy for Effective and Equitable Job Creation.’ Working Paper No.610. Levy Economics Institute

De Henau, J., Himmelweit, S. Łapniewska, Z. and Perrons, D., (2016) Investing in the Care Economy: A gender analysis of employment stimulus in seven OECD countries. Report by the UK Women’s Budget Group for the International Trade Union Confederation, Brussels. https://wbg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/De_Henau_Perrons_WBG_CareEconomy_ITUC_briefing_final.pdf

İlkkaracan, İ., 2013 ‘The Purple Economy: A Call for a New Economic Order Beyond the Green’, in U. Röhr and C. van Heemstra (eds), Sustainable Economy and Green Growth: Who Cares? LIFE e.V./German Federal Ministry for the Environment, 32–7.

İlkkaracan, İ., and Kim, K. 2019. The employment generation impact of meeting SDG targets in early childhood care, education, health and long-term care in 45 countries, Geneva, ILO, forthcoming

İlkkaracan, İ., Kim, K. and Kaya, T. (2015). The Impact of Public Investment in Social Care Services on Employment, Gender Equality, and Poverty: The Turkish Case. Research Project Report, Istanbul Technical University Women’s Studies Center in Science, Engineering and Technology and the Levy Economics Institute, in partnership with ILO and UNDP Turkey, and the UNDP and UN Women Regional Offices for Europe and Central Asia

- Published in Research, Rethinking Macroeconomics, Uncategorized