Current Situation of Care Work in South Korea: 2018 Family Survey

The Care Work and the Economy project’s 2018 fieldwork in South Korea helped us learn a great deal about how childcare and eldercare is provisioned, both in the paid and unpaid care sectors, in Korea.

The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys, including two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers and unpaid care providers. The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and recipients.

What We Learned about Family Caregiving in Korea

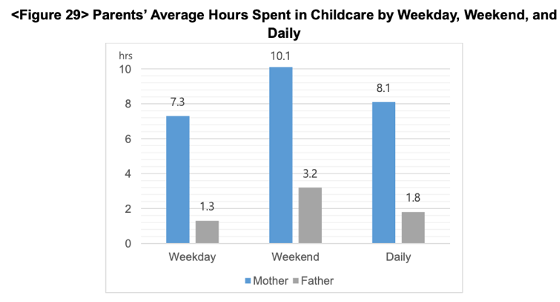

Although many families use at least one external care service to assist with childcare, 22% of respondents reported that their childcare was done only by family members (Kang et al.). Mothers spent six to seven hours more than fathers taking care of children on average.

(Kang et al.)

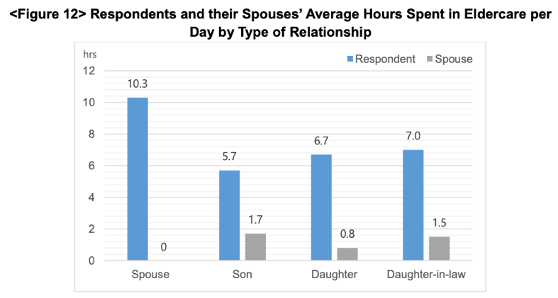

In contrast, 67% of respondents reported that their eldercare was done by family members; the rest reported using external care – usually the national LTC program. The primary caregivers were daughters-in-law (37% of the time), daughters (35%), spouses (15.6%), and sons (11%) (Kang et al.). Figure 12 shows how rather than the elder’s biological children, daughters-in-law provided the most care in terms of time, excepting the elder’s spouse.

(Kang et al.)

The cost of eldercare is shouldered solely by the primary caregiver in many cases (Kang et al., 2021)

Only 20% of family eldercare providers reported receiving regular financial support from other family members, less than 30% reported receiving help on an irregular basis, and only 8% of those over 65 years old were currently receiving LTC insurance program benefits.

Unpaid care provisioning impacts women’s employment.

The surveys showed that “families in which mothers were the sole caregiver for the child had the highest proportion of unemployed mothers, whereas families that received help with childcare from grandparents or paid care service had the highest proportion of employed mothers. With respect to both types of care arrangements, it was mostly daughters and daughters-in-law serving as primary caregiver, almost 70% of whom were unemployed.” (Kang et al.).

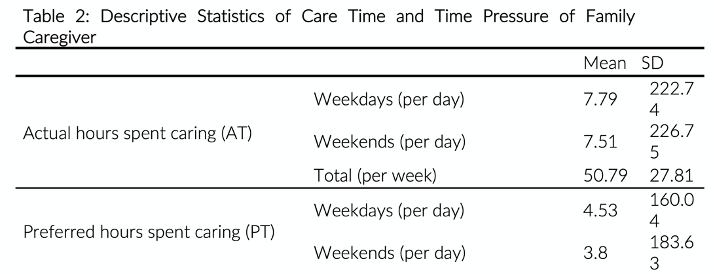

When asked about their preferred hours spent caring, eldercare workers reported a considerably lower number of hours on average than the actual hours they spent caring (see Table 2).

(Cha and Moon,2020)

Studies in the CWE-GAM Project stress concerns about the “quality of the caregiver’s life and the care they provide as well as the quality of life of the care recipient. Especially given that women are typically taking on the role of caregiver, this issue cannot be detached from concerns regarding women’s labor, women’s quality of life, and gender equality in Korea.”

Current Situation in Korea – Government Implications:

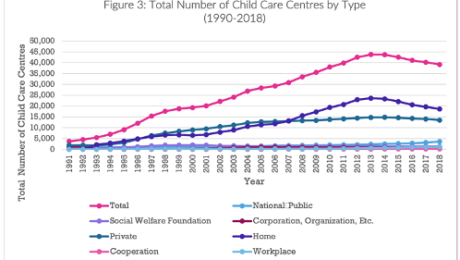

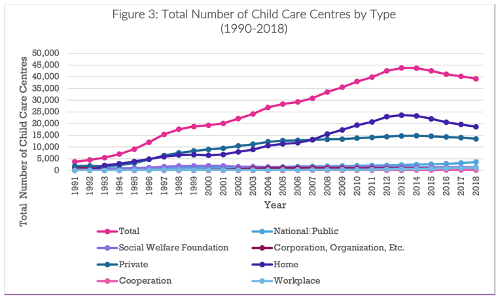

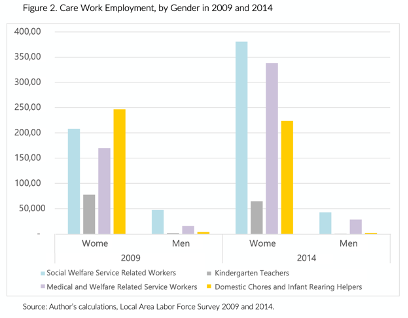

Korea currently “ranks amongst the top 10 OECD countries in terms of public investment in childcare and education” and implemented a mandatory universal LTCI program in 2008 (Peng et al 2021). Figure 2 and 3 show the evolution of child care and care work over time.

(Peng et al. 2021)

(Suh 2020)

Studies report that despite the social care expansion, “childcare and long-term care sectors are heavily dominated by women, and these care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and precariously employed. Care work is also accorded low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress” (Peng et al. 2021; Suh 2020).

Suh (2020) finds that “public investment in quality care services tends to improve the working conditions of care workers (thereby benefiting care recipients), and unregulated private provision tends to worsen them.”

This suggests that “the government and public sector should drive the effort to meet the multi-faceted challenges posed by the growing demand for care work” (Suh 2020).

“The Korean government […] continues to see care work as an extension of women’s unpaid care work and social care expenditure as something that need to be tightly controlled. A better understanding on the part of policymakers about the importance of care and the role of care work and the care economy in generating employment and positive economic growth and supporting a healthy productive economy is therefore necessary.” (Peng et al.)

This blog was contributed by Aina Krupinski Puig, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha, Seung-Eun, and Hyuna Moon. (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family

Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eunhye, Ki-Soo Eun, Jiweon Jun, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “Care

Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

Peng, Ito, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “An Overview of Care Policies and the

Status of Care Workers in South Korea.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/EHN0-R646.

Suh, Joo Yeoun. (2020). “Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea.” Care Work and the

Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/bpdf-v686.

- Published in Child Care, Elder Care, Paid Care Services, Policy, South Korea, Unpaid Care Work

Making Care Count

The COVID-19 pandemic has informed our understanding of the care economy, exposing disproportionate inequities that must be addressed to alleviate the international erasure of care workers. These issues are addressed in the latest Susan and Michael J. Angelides Lecture, in which Naomi Klein moderates a discussion between Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal and CWE-GAM researcher Dr. İpek İlkkaracan on COVID-19 and the care economy.

We live in an economic system that has traditionally deprioritized and invisibilized care workers, many of which are women of color, migrant, and poor women. The economic crisis brought on by the pandemic has consequently given policymakers and academics “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address [the valuation of care work] from an intersectional [approach],” states Congresswoman Jayapal.

The Care Crisis Exposed by the Pandemic Recession:

When mass unemployment hit during the pandemic, the cracks in the economic infrastructure of America began to show. As millions of people lost their jobs, the highest increase in the number of uninsured Americans was subsequently recorded. This high number of uninsured people is a direct consequence of healthcare being employer-sponsored. Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “Medicare For All would have strengthened the response to the pandemic…30 percent of COVID-19 deaths were related to a lack of insurance.”

While gains were made in the past decade in regards to gender equality in the workplace, Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “as soon as the pandemic hit, it was the women who went back to taking care of [their] families.” Dr. İpek İlkkaracan explains that this is because “the nature of women’s employment is often determined by their care responsibilities…unpaid care work is often articulated as one of the most significant barriers to labor force participation.” This notion was reflected in jobs reports—in December of 2020, women accounted for 100 percent of job loss, and within that, 154,000 Black women exited the workforce.

In its current state, the care economy produces a pattern of inequality that disproportionately affects women of color and migrant women. The average caregiver salary is $12.74, and the care work sector is marked by poor working conditions with no adequate social protections and low wages. This is why, as Congresswoman Jayapal notes, the fight for one fair wage is pertinent. “An increase in the minimum wage would give 32 million workers a raise, 60 percent of which are women while 1 in 4 of the women who would benefit from this increase are Black or Latina.”

A Framework for a More Caring Economy:

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan has developed a framework that acknowledges the care economy. This framework, coined as the Purple Economy (a nod to the color representative of many women’s movements), envisions a gender-egalitarian and caring economic system. Dr. İlkkaracan recommends “labor market regulations and investment in care services such as long-term care, early childhood education, education, and healthcare” as policy interventions to start the process of adequately valuing care.

Not only is investment in care important from a humanitarian and ethical perspective, but it is also conducive to economic stability. Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has revealed that investment in care services produces a high employment multiplier: for every dollar invested in care, three times as many jobs are created in the wider economy. This is because the care sector is intertwined with other sectors such as food, transport, and financial services. In the Asia-Pacific region, Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has shown that “up to four trillion dollars could be added to GDP if unpaid care work (75% of which done by women) was valued in market terms.” While this may seem astronomical, the amount of unpaid work completed globally in one day equates to 16.4 billion hours—which translates to two billion full-time jobs. Dr. İlkkaracan’s recent research also reveals that a “3.5-4% commitment of GDP to investment in care services would create 120 million additional jobs and have a large impact on poverty alleviation.”

To watch the full conversation and learn more about the Purple Economy, see below.

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan is a CWE-GAM researcher a part of the Rethinking Macroeconomics and Gender Aware Applied Economics Working Groups.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Gender-Equal Economy, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, U.S.

What is the Care Economy and Why Should We Care?

In our project, we aim to promote and advocate for gender and socioeconomic equalities. We do this by working to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes and by showing and properly valuing social and economic contributions of caregivers; and integrating care into macroeconomic policy making toolkits.

In this era of demographic shifts, economic change and chronic underinvestment in care provisioning, innovative policy solutions are desperately needed, now more than ever. Sustainable and inclusive development requires gender-sensitive policy tools that integrate new understandings of care work and its connections with labor market supply and economic and welfare outcomes.

The Care Work and the Economy Project, currently based at the Economics Department of American University and co-led by Maria S. Floro and Elizabeth King, includes more than 30 scholars around the globe, working closely together to provide policy makers, scholars, researchers and advocacy groups with gender-aware data, empirical evidence and analytical tools needed to promote creative macroeconomic and social policy solutions. In the next phase of the project, Care Economies in Context, we will be scaling up our project to include 8 different countries, in 4 global regions. I will be leading this next phase of the project, which will be based at the University of Toronto.

I define Care work is defined broadly as work and relationships that are necessary for the health, welfare, maintenance and protection of all people – young and old, able bodied, disabled, and frail. This definition may seem broad – but care– at its core is a very basic human need and a necessity. Whether we know it or now, we all participate in providing care work – paid or unpaid, and in receiving care every day.

By care economy, I am referring to the sector of economy that is responsible for the provision of care and services that contribute to the nurturing and reproduction of current and future populations. More specifically, it involves child care, elder care, education, healthcare, and personal social and domestic services that are provided in both paid and unpaid forms and within formal and informal sectors.

Care work is important because it is important work that sustains life. It is also important now in particular because it is one of the fastest expanding economic sectors and a major driver of employment growth and economic development around the world. For example, across the OCED, the service sector economy now accounts for over 70 percent of total employment and GDP. In lower- and middle-income countries, it is estimated to comprise nearly 60 percent of GDP. Within the service sector economy, care services is one of the fastest growing subsectors.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that the global employment in care jobs is expected to grow from 206 million to 358 million by 2030 simply based on sociodemographic changes. The figure will be even more dramatic to 475 million if governments invest resources to meet the UN sustainable development goal targets on education, health, long-term care and gender equality.

In Canada, the service sector already makes up for 75 percent of employment and 78 percent of GDP. Within this sector, healthcare, social assistance and education services are key drivers of economic and employment growth. In the U.S., healthcare is already the largest employer, larger than steel and auto industries put together. In short, our current and future economy is and will be increasing dominated by care services and care work.

However, at the same time, much of the care work continues to be performed for no pay, by families and friends, at home and in communities. This unpaid care work is not including in in our national GDP because GDP only takes into account work that is done for pay in the formal market. Therefore, if we only look at the GDP as a measure of the economy and economy growth, we miss a huge segment of the economy and economic activities. As the pandemic has shown, without both paid or unpaid care work, our economy will not be able to function effectively, nor would it be able to sustain itself.

What we are trying to do in our project is to make the care economy clearer and more visible by measuring and mapping out the size and shape of the economy, and to develop macroeconomic models that would help policymakers and civil society actors to develop better policies and better strategies to ensure more sustainable and equality inducing economic growth.

Listen to the full talk “The Care Work and the Economy Project” to learn about what the care economy is and why we should know more about it, particularly now.

The blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care research cluster

- Published in Canada, Child Care, Economic Modeling, Elder Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, OECD

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part I

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” This discussion delves into the foundation of project itself, its context, the analytical tools utilized in the research, as well as the external factors that have served as the catalyst for the work being done.

The Care Work and the Economy Project was developed after a group of feminist economists observed that in the effort to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes, as laid out within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, there were aspects of care work that needed to be addressed. The project includes 35 scholars from all around the world that are working to develop innovative analytical tools. The research has been applying and testing these tools in South Korea, a country that quickly industrialized in the 70s and 80s and therefore witnessed a very rapid demographic change in fertility and life expectancy.

The care economy, which is inclusive of caring for those that cannot care for themselves, underpins the production of all economies within society. This begins with the fact that if people stopped having children, which require care, then the economy would come to a halt due to lack of labor force. Generally, care work has a tendency to be undermined through a lack of gender awareness in macroeconomic modeling, which does not address care needs in any adequate manner. This aspect is also neglected within the policy making discourse, with the current economic paradigm failing to take into account the necessity for care work to achieve economic growth.

Economic models that display growth also fail to take into consideration social elements, making the assumptions that, for example, children will be cared for despite the lack of social investment into care. However, with care work there comes social, political and economic significance. The Care Work and the Economy project is working to demonstrate what a care focused macroeconomic model can reveal through the implementation of the analytic tools being developed and implemented through the research.

The absence of the care economy within macroeconomic models is in large part due to it being “invisible” since the work often unpaid. This has led to the neglect of care needs despite unpaid care work providing indispensable services in terms of economic activity and growth. The result is an emerging care crisis that has manifested itself in terms of uncared for elderly, sick and children. Furthermore, the crisis has provoked a form of silent protest against long unpaid work hours performed by women, leading to a decline in marriage and fertility rates. This in turn has resulted in a reproduction crisis.

The Care Work and the Economy project researchers are developing and using innovative analytical tools to bring care to the forefront, along with a deeper understanding of the nature of care work, while illustrating the intersectionality between care provisioning, economic growth and distribution. Although these analytical modeling tools are currently being applied in South Korea, the project believes they can be adopted and implemented into other countries as long as the provision of care is taken into context of those countries. The project research shows that governments have an important role and duty to invest in care provisions as well as comprehensive national care plans. One of the key findings is that it is important to take into account demographic change and climate change along with economic and structural changes taking place in policy making. This is a tall order but necessary to sustain economies and provide a future for next generation.

Link to Part 2 of this blog here.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

A New National Model for Preschool and Childcare in the U.S.

Frustrated with decades of inaction at the national and state level, residents of Multnomah County, Oregon put a measure on the ballot this past November to create a free, year-round, universal preschool program for all three and four year-olds in the county. Approval was resounding, the vote nearly two to one in support.

Despite years of compelling evidence for universal preschool as a powerful economic development strategy that improves educational outcomes while fighting poverty and inequality, as well as gender and racial disparities, the U.S. lags far behind many nations in the provision of early childhood education and care. But – unlike other desperate needs such as affordable housing and health care – early childhood education is relatively inexpensive, making it possible for a city or county to mount its own program.

The preschool model being created for the city of Portland, and the rest of Multnomah County, should set a new standard for public preschool programs in the U.S., meeting the needs of children, their families and preschool staff. To help children thrive and obtain the most from their later education, Multnomah County will work with a range of providers to offer a high quality program, in different languages and cultures, and in a variety of settings, including schools, centers, and family child care. The program will attain full universality within ten years, prioritizing the enrollment of children from communities of color and families with lower incomes in the early years as the program builds.

To ensure that the program works for families, they’ll also have a choice of schedules, including full and part-time, school year or year-round, and weekends as well as week days, for up to five days a week. All children may attend without cost for up to six hours a day, with ten hours a day free for families in the lower half of the income distribution.

To retain the skilled, experienced, dedicated – and almost entirely female – staff so critical to quality, teachers’ salaries will double the going rate, to equal those of kindergarten teachers. The wage floor for all classroom workers, including aides and assistant teachers, will be significantly above the minimum wage, starting at just under $20 an hour in the autumn of 2022 when the first children will be enrolled.

No public preschool system in the U.S. has yet paid a living wage to all staff members, despite cripplingly low levels of staff retention. Economist Catherine Weinberger has shown that, in the U.S., four of five employed women with college degrees in early childhood development and education do not work with young children. By contrast, high proportions of college graduates educated as nurses, accountants and others work in jobs that draw directly on their academic training.

Further, Multnomah County’s new universal preschool program will be funded by a county income tax levied on approximately eight percent of the county’s highest income households, addressing skyrocketing economic inequality and the forty-year concentration of income at the very top.

The Multnomah County ballot measure campaign was supported by an undeniable coalition of teachers, unions, organizations representing communities of color, civic and feminist groups, small business owners and environmental advocates– not to mention galvanized parents, child care workers, preschool providers, public health care workers, doctors, economists, school board members and elected officials. Two separate campaigns worked independently for years to prepare a ballot measure, emerging to find themselves aimed at the same election. The more ambitious was led by the Portland chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America while the other was headed by a philanthropy, called Social Venture Partners, working with an elected County Commissioner. The two campaigns were able to merge on their strongest combined program, after the bolder plan gathered thirty-two thousand signatures, more than enough to qualify for the ballot.

Key to our success, I believe, was creating a program that works for children, parents and workers. Too often in the U.S., fear of raising taxes has led to small, part-time and ill-paid programs serving only the least advantaged, and supported by a limited base of advocates for children from lower-income households. High quality, universal programs are not only more successful at improving educational outcomes for disadvantaged children, but enjoy the popularity necessary to sustaining funding into the future while allowing parents to work more hours or gain additional schooling.

This blog was contributed by Mary C. King who is Professor of Economics Emerita at Portland State University, Vice-President of the Oregon Center for Public Policy, Co-Chair of the Oregon Scholars Strategy Network and a founding board member of Family Forward Oregon. She has spent the past three years campaigning for universal preschool in Multnomah County, where voters decisively approved the creation of a free, year-round, full-day universal preschool program on November 3, 2021.

- Published in Child Care, U.S., Universal Preschool

Care Work and the Economy: Fieldwork in South Korea

The 2018 fieldwork for the CWE-GAM project aimed to understand and measure care work in the South Korean context in order to inform gender-aware care macroeconomic models. The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys. The quantitative surveys include two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers in eldercare and childcare (Paid Care Worker Survey) and two sets of questionnaires for the unpaid care providers in the households for eldercare and childcare (Care Work Family Survey). The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and care recipients.

PAID CARE WORK SURVEY

The Care Work and the Economy Paid Care Work Survey includes two sets of questionnaires for eldercare and childcare workers and a 24-hour time use diary. A purposive sampling method was used to sample 600 paid care workers, 300 eldercare workers and 300 childcare workers, because the exact size and distribution of paid care workers in Korea are unknown. Paid care workers are defined as those working in institutional settings, at the care recipients’ home, and informal workers working without formal contracts. The sample targeted those providing care of the elderly and children’s daily lives, excluding kindergarten teachers and health care workers at hospitals and medical eldercare facilities. The sample of paid care workers associated with institutions were allocated to reflect the national distributions of eldercare facilities and daycare centers, and the sample of informal care workers were equally allocated across regions.

The Paid Care Worker Survey collected detailed and comprehensive information on the care work provided by paid care workers. The stylized questions and time use diaries of paid care workers collect information on the type, intensity, duration, and evaluation of care work from the perspective of paid care providers. The survey aimed to investigate the characteristics and working conditions of paid care workers, including their background, condition of contract, working environment, task arrangement, and subjective evaluation of the working conditions, and their well-being. The 24-hour time use diaries were collected to provide insights on how the day of a care worker is constructed and how care work is associated with other domains of daily life and time use, which can be analyzed in tandem with the stylized questions on the well-being of care workers.

FAMILY CARE WORK SURVEY

The Care Work Family Survey also consists of two sets of questionnaires for main care providers in the household engaged in childcare and eldercare respectively. 1,000 cases of main care providers in the household were interviewed (500 cases for childcare, 500 cases for eldercare) using a stratified cluster sampling method. Because it is not possible to know the distribution of the population of people who provide unpaid care in a society, children aged below 10 and the elderly aged over 65 were treated as the target population from which to draw the sample. Based on the distribution of the 2018 National Resident Registration Data in Korea, we allocated the number of target households to each area, identified eligible households with elderly or children in need of care, and then selected eligible respondents within the selected households.

The Care Work Family Survey was developed to provide a detailed and comprehensive picture of the care arrangements in South Korea. The survey aimed to investigate how care provision is arranged for the children and the elderly and why it is arranged in such ways. Therefore, the survey collects information from the main care provider, not the care recipients themselves, as it is often the case that the main care provider is the one who knows most about the care arrangements.

After screening for eligibility, respondents were asked questions on their demographic characteristics and information on the respondent, care recipients and other household members. Respondents were asked about the specific activities involved with their care work including frequency, subjective intensity, preferences and willingness to engage in the activities. Information on care arrangements were collected as well including how the care work is shared within the household, whether there are any gaps of care provision, the history of caregivers, use of care services, and decision-making of using care services. Other information such as financial responsibility and burden, experience and evaluation of care work, dual care burdens and well-being of caregivers were collected.

IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

The purpose of the in-depth interviews of paid and unpaid caregivers was to provide useful care narratives based on the Korean context to inform macro-modelling. The qualitative research team intervened 25 family caregivers of the elderly, 20 family caregivers of children, 20 paid care workers for elderly, and 31 paid care workers for children. The interviews of family caregivers focused on the decision-making process and evaluation of care arrangements for the elderly and children. Interviewees were also asked about their experiences with caregiving. The interviews of paid caregivers focused on dual care burdens in terms of paid care work in addition to unpaid care work in the home.

SIGNIFICANCE AND LIMITATIONS

The fieldwork for paid and unpaid care work in Korea was designed and conducted to investigate the nature and context of care work in Korea. The Paid Care Worker Survey and Care Work Family Survey have distinct characteristics that contribute to enhancing our understanding about the experience of caregiving in Korea. First, the set of questions that have been developed can be commonly applied to caregivers regardless of the type of care work or the subject of care to enable comparative analysis on the experience of caregiving. Second, not only the caregiving situation, but also the broader aspect of the caregiver’s life including the preferences and attitudes of the caregiver have been studied. Third, the surveys collect detailed information on how care is arranged. Lastly, a caregiver focused 24-hour time use diary has been developed to understand which activities could be considered as care.

This fieldwork only included certain types of caregivers due to the limited budget, time, and scope of the fieldwork. For instance, the sample did not include caregivers for the disabled, caregivers who work at hospital settings, and migrant care workers, despite their importance. Also, as the family survey for childcare limited the respondents to ‘mothers’, and consequently fathers and grandparents were excluded. We hope that the future rounds of surveys can be extended to have a larger sample size and to include a broader range of caregivers. Questions explored in this fieldwork provide important information about the experience of caregiving in Korea, and we hope the fieldwork in Korea can inform fieldwork in other countries.

Learn more about care arrangements and activities in South Korea based on our analysis on the 2018 Care Work and Family Survey here.

This blog was authored by Bong (Regina) Sun Seo, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group

Caregiving in Crisis and How to Fix It: Special Issue from The American Prospect

Last month, the Prospect released a special issue featuring a series of articles surrounding family care,“Caregiving in Crisis and How to Fix It.”

To accompany this issue, a special event was hosted by the Prospect in which various activists, writers and caregivers discussed family care, child care, elderly care, paid family leave to provide care, and long term support for caregiving services.

This event featured:

David Dayen, executive producer for the Prospect

Ai-jen Poo, co-director of Caring Across Generations,

Lynnea Redmon-Williams, a caregiver working fulltime

Tasmiha Khan, Prospect contributing writer

Rhacel Salazar Parreñas, Professor of sociology at the University of Southern California

Brittany Gibson, Prospect writing fellow

See the video below for the entire discussion:

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Long Term Care Sector, Special Issues

Spirals of Inequality: A Women’s Budget Group Special Report

The Women’s Budget Group Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy, launched in February 2019, is an expert-led project aimed at developing economic policies that promote gender equality across the United Kingdom. The Commission utilizes a number of avenues and tools to achieve this objective, one of which is the recent release of the report “Spirals of Inequality: How Unpaid Care is at the Heart of Gender Inequalities.”

This first report released by the Commission seeks to trace the problem of how gender inequalities in the UK are produced and maintained by observing the problem through the following perspectives:

Unpaid Work: Women Continue to do the Lion’s Share

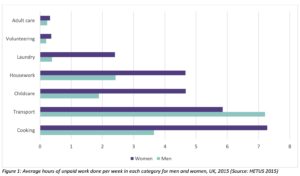

The unequal division of labor within unpaid care work is at the heart of gender inequality in the UK, with women taking on 60% of the unpaid work on average. This includes care work, cooking, and cleaning among other tasks.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

Limiting Opportunities for Paid Work: Women More Likely to Work Part-Time and Earn Less

This phenomenon puts a disproportionate strain on women and contributes to gender inequality. Mothers with young children are 3-4 times more likely to work part-time, and women, in general, are far more likely to be in precarious forms of employment such as temporary work. This is especially true for women of color. The part-time work conundrum is driving the gender gap, and on average women earn 43% less than men. Furthermore, a pay gap of 8.9% persists, further exacerbating this issue. Again, this being more predominate with women of color.

Despite women becoming increasingly educated, they persist in being overrepresented in low-wage sectors of the economy such as health and social work. Feminist economists have argued that a reason behind this is such sectors are viewed as an extension of a women’s “natural” work.

These issues create a perpetual cycle that allows for the inequality between men and women to continue.

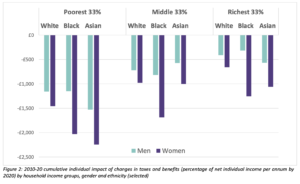

Life Course Implications: Benefits Make Up a Larger Portion of Income and Austerity Hits Harder

Among single households living in poverty, those led by women make up for 86%. Furthermore, pensioners living alone are far more likely to be at the poverty level if that individual is a woman. Since tax reforms began in 2010 throughout the UK, women have also been hit hardest. These benefits make up a large portion of women’s incomes and cuts to these benefits and tax giveaways benefit those fitting into a higher wealth bracket.

Public Services: Women Hit Hardest by Cutbacks

Cuts to public spending throughout the UK have also hit women disproportionately hard, as women are most likely to utilize public services. The poorest families and especially those in poverty-level households led by women have taken a particularly bad hit; many single mothers have had to cut living standards by up to 10% as a result of a cut to public services between 2010 and 2017.

Furthermore, these cuts have put a greater burden on family members to provide care for the elderly members of their family, much of this falling onto female members. This often comes at the expense of their own employment.

Violence Against Women: “Cause and Consequence” of Women’s Economic Equality

All of the factors that lead to the economic disparity between men and women also make it increasingly difficult for women to leave abusive partners. Furthermore, poorer households have higher rates of domestic abuse, and this perpetuating poverty limits women’s options while increasing their vulnerability.

Moving Forward: Next Steps for the Commission

The WBG Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy is striving to develop an alternative economic approach aimed at addressing these issues. Through this initiative, they aim to build an economy that is desirable, economically feasible, and necessary for fairness, sustainability, and resilience. To learn more about the Commission and its work, sign up to attend the upcoming webinar “Creating a Caring Economy: A Call to Action” on September 30, 2020.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy

Inequalities in access to U.S. care services

In the U.S., states and localities are beginning to ease social distancing policies resulting from the pandemic. With many workplaces calling Americans to return to work, the nation’s care services system, what was already broken, is now in dire need of repair or replace.

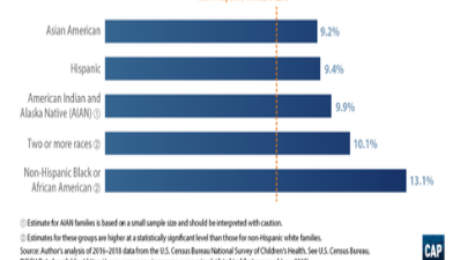

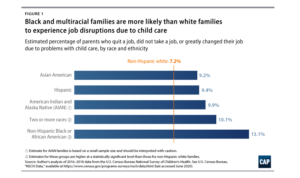

According to a recent analysis by the Center for American Progress (CAP), the lack of adequate child care services in the U.S. negatively affected communities of color before the pandemic, as parents of color were more likely than their non-Hispanic white counterparts to experience child care-related job disruptions that could affect their families’ finances.

The analysis uses the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to show that before the pandemic, Black and multiracial parents experienced child care-related job disruptions—such as quitting a job, not taking a job, or greatly changing their job—due to problems with child care at nearly twice the rate of white parents.

For Black workers and workers of color, decades of occupational and residential segregation has translated to less access to telework, and therefore less flexibility within their responsibilities for young children or elders. In fact, most Black workers and workers of color (especially those who are women) have had to work through the pandemic in essential frontline occupations.

The analysis shows that prior to the pandemic, adequate and affordable child care services was short in supply, particularly for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous families. In fact, more than half of Latinx and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) families have experiences living in a child care desert – which is an area suffering from an inadequate supply of licensed childcare.

Using child care services as an example, the analysis shows that disparities will likely worsen in the aftermath of the pandemic. A previous CAP analysis estimated that nearly 4.5 million child care slots could disappear permanently as a result of COVID-19, effectively cutting an already inadequate child care supply in half. Recent data suggest that this impact is already being felt, with more than 336,000 child care providers—many of whom are immigrants, African American, or Hispanic—losing their jobs between March and April.

Allowing care services to flounder should not be an option; a broken and inadequate care system would slow the nation’s economic recovery and in addition to deepening existing economic and racial inequalities.

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Race Inequality

Frontline Care Workers in the U.S.

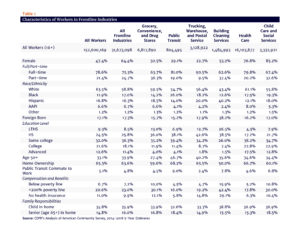

A recent report on Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in U.S. Frontline Industries by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) looks at six broad industries, employing grocery store clerks, warehouse workers, bus drivers, and care workers – including nurses, care workers at child care and residential care facilities, as well as household and community service workers.

Based on CEPR’s analysis using the American Community Survey (2014 – 2018), over half of all essential workers in the industries examined are employed in care services. More than a third of these workers are over the age of 50; and before the pandemic, nearly a quarter were living in low-income households and about half lived with a child or a senior at home.

At the national level, women workers are overrepresented in frontline industries. About one-half of all workers are women, but nearly two-thirds (64.4 percent) of frontline workers are women. Women are particularly overrepresented in care-work related industries – Healthcare (76.8 percent of workers) and Child Care and Social Services (85.2 percent).

Black and Hispanic workers, as well as other people of color are also overrepresented in many frontline industries occupations. Black workers are most overrepresented in Child Care and Social Services (19.3 percent of workers). Hispanic workers are especially overrepresented in Building Cleaning Services (40.2 percent). Immigrants are also overrepresented in Building Cleaning Services and in many frontline occupations in other frontline industries.

The report calls on U.S. congress to include important protections for frontline workers in its response to COVID-19 – including comprehensive health-care insurance, paid sick and family leave, free child-care, student loan relief and other labor protections related to workers’ health, safety and immigration status.

About the report:

A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries. Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad. Center for Economic and Policy Research. April 2020.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19

- 1

- 2