“Girly Issues” Are Now the Country’s Issues

Dr. Nancy Folbre, an Advisor and Researcher of the CWE-GAM project and a groundbreaking feminist economist was among the first to sound the alarm about the care crisis. Dr. Folbre’s work on the care sector, once considered “just girly issues” by fellow economists, are now recognized as issues belonging to the U.S.. Previously the recipient of the 1998 MacArthur “genius” grant, Dr. Folbre’s research has journeyed from “fringe idea to more mainstream policy.”

Once cast aside in policy discussions, the care crisis is finally getting the spotlight it deserves after the pandemic forced many schools and child-care centers to close, leaving “ten million mothers of school-age children out of the workforce.” The pandemic is forcing policymakers to finally face the cracks in America’s care infrastructure that Dr. Folbre and other experts have long pointed out— “a system where working parents do not have reliable, affordable child care is one where they cannot reliably build a career.”

To learn more about Dr. Folbre’s work on care, visit her blog Care Talk and read her recent book The Rise and Decline of Patriarchal Systems.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics

Biden’s American Jobs Plan Could Be Monumental for the Care Economy in the U.S.

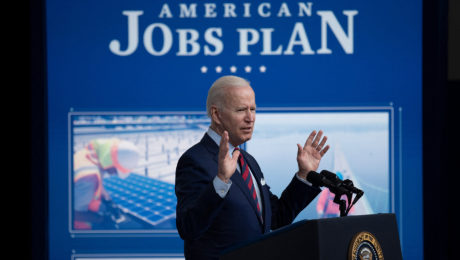

Last month, the Biden administration revealed the details of the $2 trillion American Jobs Plan.

The plan recognizes that investing in the care economy, as with investments in traditional infrastructure, can lift incomes, unleash productivity, and pave the path towards a more equitable economic recovery and growth.

Addressing the care crisis

Built into the plan is a pledge to “solidify the infrastructure of our care economy by creating jobs and raising wages and benefits for essential home care workers.” The plan calls for Congress to invest $400 billion towards expanding access to quality, affordable home- or community-based care for aging relatives and people with disabilities. These investments will help Americans to obtain the long-term services and support they need, while creating new jobs and offering care workers a long-overdue raise, stronger benefits, and an opportunity to organize or join a union and collectively bargain. Research has shown that increasing the pay of care workers leads to better quality care overall. Through creating well-paying care jobs with benefits and o collectively bargaining rights, as well as building state infrastructure, the plan aims to improve both the quality of job for care workers and the quality of service for care recipients.

Lack of access to childcare makes it harder for parents, especially mothers, to fully participate in the workforce, hurting families and hindering U.S. growth and competitiveness. In areas with the greatest shortage of child care slots, women’s labor force participation is about three percentage points less than in areas with a high capacity of child care slots. The pandemic has severely exacerbated this problem with more than 1 in 4 facilities still remaining closed as of December 2020. President Biden is calling on Congress to provide $25 billion to help upgrade child care facilities and increase the supply of child care in areas that need it most. These funds are to be provided through a Child Care Growth and Innovation Fund for states to build a supply of infant and toddler care in high-need areas. Also included in this $25 billion is a call for expanded tax credits to incentivize businesses to provide care facilities at their establishments. This will grant accessible, high quality care and learning environments for children of employees. This particular part of the plan is structured so that employers will receive 50 percent of the first $1 million of construction costs per facility.

Investment in care is investment in infrastructure

As Cecelia Rouse, Chair of the Economic Advisors for the Biden administration, recently indicated during a recent press conference, we need to “upgrade our definition of infrastructure” to include the care economy. Rouse defended the Biden administration’s plan to spend $400 billion of the infrastructure plan’s budget on the care economy, defining it as a legitimate infrastructure investment and a key component to addressing economic inequities in the U.S. The care economy is critical to U.S. economic activity, and its absence would greatly hinder economic productivity. The inclusion of care work and the care economy in the American Jobs Plan is a critical first step in mending a critically broken care infrastructure in the U.S.

Still, it is only the first step. The U.S. is the only industrialized nation that fails to provide national paid family leave and medical leave programs, and where hundreds of thousand sit on waiting lists for desperately needed home care. LeadingAge, which represents service providers in the sector, estimates that half of all Americans will need long-term services and support after turning 65, and that by 2040, a quarter of the U.S. population will be 65 or older. In addition to the President’s proposal for the care economy, we also need investments to finally put America on a path to universal childcare and early learning, national paid family and medical leave and paid sick days for all workers. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed both the importance of care work and the vulnerabilities of our care infrastructure. At the same time, it has also created an opportunity for us to rethink the value of care and care work, opening ways for us to rebuild a more resilient care infrastructure and a more inclusive economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Economic Recovery, Policy, U.S.

Women and the Pandemic in the U.S.

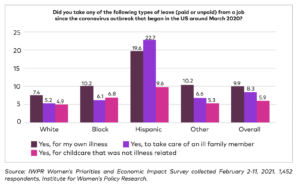

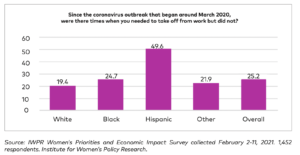

Institute for Women’s Policy Research released a report in February 2021”IWPR Women’s Priorities and Economic Impact Survey” outlining a recent poll of 1452 women in the U.S. The findings are backdropped by the experience of women throughout the pandemic and resulting economic turndown, in which 2.35 million women have left the workforce since February 2020.

Some of the key findings from this survey are:

- 1 in 4 women report that they are worse off financially than one year ago

- Nearly half of all women are worried about the financial situation of their families

- 1 in 4 women report having needed to take time work off but did not do so

- 40% of women reported care demands stopped them from working or forced them to reduce hours

- 69% of women support paid sick time to have a child, recover from a serious health condition, or care for a family member

- 20% of women with children want the Biden administration to address childcare and education in the first 100 days

In terms of women experiencing reduced paid work as a result care demands, this has also been pointed to within recent working papers put out by the

The impact of care demands on women’s paid work is explored in a number of Care Work and the Economy Working Paper Series. For instance in two recent papers, “Gender Wage Equality and Investments in Care: Modeling Equity and Production” and “Parental Caregiving and Household Dynamics”.

Education and childcare were listed among the top priorities for the Biden administration to address within the first 100 days among survey participants. This is largely because women’s ability to reenter the workforce largely depends upon safe reopening of schools and childcare facilities.

Latinas have been hit particularly hard according to this survey, reporting the highest levels of taking leave from jobs in order to provide care. However, across all ethnicities, 69 percent of women expressed strong support for paid sick leave and the ability to take time away from work to provide care or recover from illness.

The Unites States remains the only high-income country in in the world that fails to provide guaranteed paid sick or family leave for workers. The Family Medical Leave Act, which provides unpaid job protection, and only for about 56 percent of workers. The Families First Coronavirus Relief Act has provided access to paid leave as a result of the pandemic but falls short in the fact that more than 100 million workers are excluded from this because they are caregivers.

In order to address the many issues identified throughout this survey, there is strong need for targeted programs and policy solutions that will aid a gender equitable recovery. This recovery should not only address immediate short term needs but include long term strategies that will create more resilient systems that recognize the contributions of women to the workforce, society and family structure.

IWRP specific recommendations for the short term are:

- Continuing economic impact payments

- Expanding access to affordable healthcare

- Providing paid sick and medical leave

- Raising the federal minimum wage

- Building a new childcare infrastructure

Equitable economic recovery necessitates a national care system that meets the needs of all families, raises wages and provides quality childcare, treating it as a public good instead of a private obligation.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Policy, Policy Briefs & Reports, U.S.

A Time for Reflection on Care

The world outside my study is churning and whirling… as it is engulfed with the fast-evolving health situations in communities around the globe. There are many unknowns about the

COVID-19 illness that has spread rapidly in every continent and the presence of uncertainty—big time—has rattled governments, shaken markets, and upended our daily routines, to say the least.

While I join the hundreds of millions of people who constantly check the news online and in newspapers, radio and/or tv, I also take time to pause. These moments allow me to reflect on

what this difficult time that we are all experiencing means and what it says about us—as

individuals, as members of communities, and as citizens of the world.

For one, I find that:

- each individual action has multitudes of rippling effects, large and small, on others;

- the real world oscillates between predictability and unpredictability; it requires each of us to constantly assess the balance between taking caution and taking risk;

- the distinction between self-interest and altruism (promoting others’ interests) becomes more blurred given the pervasive interconnectedness of our lives;

- adaptation and flexibility are vital life skills that we need to have not just now but at all times;

- we have the ability to change as we obtain more information and as conditions around us change; the notion of fixed tastes and preferences is outmoded;

- the skills that we must hone and develop should prepare us not only to live in a competitive world but also to be able to work together, coordinate and cooperate with one another; for the greater good requires collective action.

As the impacts of the COVID-19 spread intensify, there is growing recognition among governments and the public that traditional efforts for dealing with shocks and managing risks through conventional emergency responses are inadequate. Strategic thinking is needed as much as the ability to respond quickly and to take proactive measures. There is an urgent need to build the adaptive capacity and longer-term resilience of communities and societies.

One striking fact about the current global pandemic is its tremendous effect on the care sector. This includes not only the health care systems employing doctors, nurses, aides, and other health professionals but also the unpaid care labor provided by family members, neighbors, and kin.

Many are changing their daily life patterns to provide further assistance and care support for those who are vulnerable such as their parents or grandparents and for those who are self-quarantined. Many more are willing to take the risk of exposure to care for those who have tested positive and are ill but are staying at home because the healthcare system is inadequate, inaccessible, and/or overwhelmed. The shutdown of schools and daycare centers further adds demand for unpaid care. Parents are struggling to care for their children while at the same time trying to tele-work from home.

“How can I write or have meetings with my six-year old around?”

The cloak or mantle that hides the emerging crisis of social reproduction, or the under- provision of care for people who depend on it, is removed. This global pandemic exposes the heavy demand on those who carry the responsibility for providing care for the sick, the young and the frail elderly, the vast majority of whom have been women. It has upended preconceived notions such as: each individual is a ‘Robinson Crusoe’ in families that can find their own solutions to provide care, and that one’s ability to pay should determine who accesses care in the private sector.

The Care Work and the Economy Project joins the efforts of other organizations, research institutions and advocacy groups towards making the care sector visible to policymakers. The heavy care burden that is now being shouldered by health care systems, households, communities and countries throughout the world makes it imperative to bring care work out of statistical shadows and to remove the veil of ignorance in economic policymaking.

Let us hope that this time is truly different and that the jolt brought about by the current pandemic leads to more openness in the academic community and among policymakers towards a paradigm shift and policy change.

March 2020

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, elderly care, Maria Floro, Policy