The Covid-19 Care Penalty

In the U.S., as elsewhere, essential workers have been rightly praised for their willingness to take on additional risk and stress. Their commitment to helping patients, students, and customers face-to-face went beyond the ordinary requirements of earning a paycheck. Yet some essential workers faced more serious risks of infection than others, and differences in pay among them were also significant. The abrupt creation of a new category of workers based on social need, rather than market forces, dramatized an important question: why do we often see a disjuncture between the social value of work and its private, pecuniary reward?

Feminist research addresses this question in a number of ways, emphasizing factors such as employer discrimination, monopoly or monopsony power, and intersectional differences in the relative bargaining power of distinct groups of workers. The distinctive features of care work—intrinsic motivation, emotional skills, team production, and positive spillover effects—have also received attention. Leila Gautham, Kristin Smith and I have been building on previous research on care penalties to show that essential workers in care services (health, education, and social service industries) are paid less than other essential workers (in law enforcement, support and waste services, transportation, agriculture, retail and financial industries) with comparable personal and work characteristics, a pattern with especially costly consequences for women. Low-wage workers such as health aides are especially vulnerable, but care penalties also help explain the vulnerability of doctors and nurses in ways mediated by unique institutional features of the U.S. health care system.

A paper on this research is now under review. Once this process is complete, I’ll come back with more details.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on June 11, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in COVID 19, Feminist Economics

Frontline Care Workers in the U.S.

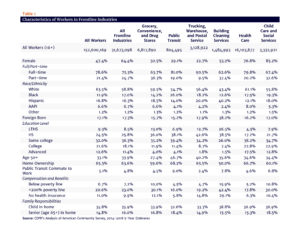

A recent report on Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in U.S. Frontline Industries by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) looks at six broad industries, employing grocery store clerks, warehouse workers, bus drivers, and care workers – including nurses, care workers at child care and residential care facilities, as well as household and community service workers.

Based on CEPR’s analysis using the American Community Survey (2014 – 2018), over half of all essential workers in the industries examined are employed in care services. More than a third of these workers are over the age of 50; and before the pandemic, nearly a quarter were living in low-income households and about half lived with a child or a senior at home.

At the national level, women workers are overrepresented in frontline industries. About one-half of all workers are women, but nearly two-thirds (64.4 percent) of frontline workers are women. Women are particularly overrepresented in care-work related industries – Healthcare (76.8 percent of workers) and Child Care and Social Services (85.2 percent).

Black and Hispanic workers, as well as other people of color are also overrepresented in many frontline industries occupations. Black workers are most overrepresented in Child Care and Social Services (19.3 percent of workers). Hispanic workers are especially overrepresented in Building Cleaning Services (40.2 percent). Immigrants are also overrepresented in Building Cleaning Services and in many frontline occupations in other frontline industries.

The report calls on U.S. congress to include important protections for frontline workers in its response to COVID-19 – including comprehensive health-care insurance, paid sick and family leave, free child-care, student loan relief and other labor protections related to workers’ health, safety and immigration status.

About the report:

A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries. Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad. Center for Economic and Policy Research. April 2020.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19

UN Women: COVID-19 and the Crisis of the Care Economy

In a recent UN Women blog post, Silke Staab explores ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic that has swept the globe is further compounding the risk and strain put upon women in the care economy – both paid and unpaid.

Women comprise 70% of health workers globally and even higher shares of care-related occupations such as nursing, midwifery and community health work, which all require close contact with patients. The risks these front-line workers take to save lives are compounded by poor working conditions, low pay and lack of voice in health systems where medical leadership is largely controlled by men.

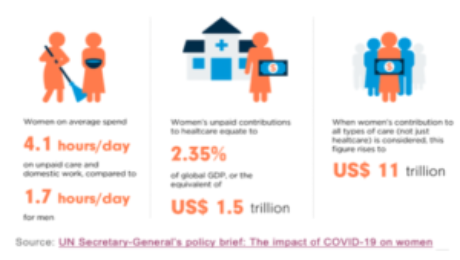

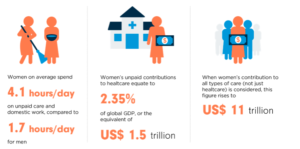

It is estimated that unpaid health care, in which the burden primarily fall onto women, is equivalent to a staggering $1.5 trillion globally. When factoring in all other types of care work, that figure climbs to $11 trillion. Furthermore, community health workers that receive no compensation, again mostly comprised of women, are vital to the health and wellbeing of communities all over the world. These care workers are in desperate need of proper equipment, training and financial support in the face of this current pandemic.

Source: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women

The increased burden of childcare due to school closures and social distancing is also bound to negatively affect the well-being of the women taking on these tasks. This is further exacerbated by the loss of assistance from elders in the family, who must keep themselves protected from COVID-19 due to being in a vulnerable category.

On the flip side of that is the reliance of elderly people on the informal care of their family members, but this reliance puts them at greater risk of being exposed. Providing these family care workers with the proper assistance and protective gear in order to continue their duties while minimizing the risk to their loved ones is an essential first step in facing this particular challenge.

Although this pandemic has caused an immense strain on the care economy, the situation has created an opportunity to reevaluate priorities and reassess the economic value of these essential services being provided through care work. A people-centered plan for economic recovery should take this into account and prioritize long-overdue investments in the care economy.

Silke Staab is a research specialist at UN Women.

This blog was originally posted on the UN Women website on April 22, 2020. Read this blog post here.

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities, UN Women

Responsibility Time

If there was ever a time we urgently needed to know more about time use, that time has come. The Covid-19 pandemic utterly changed daily rhythms for many sequestered households and the “opening up” process closed down some old routines.

I’ve done extensive work with time use data, have been in touch with several people/groups trying to measure the impact of the pandemic, and am trying to follow results being reported in other research.

My reactions are conditioned by long-standing concerns about survey methodology.

It is surprisingly hard to get an accurate picture of how people use time, because we all tend to do more than one thing at once. Also, doing is not the whole story—being present, available, on-call, and taking responsibility for others is typically far more time-consuming than specific acts of helping. This is especially true for the care of young children, people who are sick, frail, or suffering a disability.

Sheltering-in-place guidelines, combined with the social distancing, have probably had a much bigger impact on where people are, who they are with, and what they are responsible for—than on their activities.

Yet most surveys focus on activities alone, in several variations. They ask stylized questions about how much time people spent in various activities in a given time period, such as the previous day. Or, they persuade respondents to fill out a time diary in which they report what they did in specific intervals (such as every ten minutes) between waking up in the morning and going to sleep at night.

Note the prominence of the words “activities” and “doing” in both cases. Some surveys reach a bit further. The annual American Time Use Survey (ATUS), for instance, asks people if a child under the age of 13 was “in their care” while they engaged in activities. While the ATUS describes such care as a “secondary activity,” it is better interpreted as a responsibility that strongly influences the way that people organize their activities and plan their schedules.

Being on-call to provide care also creates vulnerability to brief but sometimes incessant interruptions whose impact is probably difficult to measure.

This is important because sheltering in place and sequestration almost certainly increased supervisory demands as much (if not more than) active care of young children. At the same time, social distancing guidelines limited peoples’ ability to provide any supervisory care or assistance to elderly or hospitalized family members.

Furthermore, these constraints are likely to be in place for some time—over the summer, children’s activities outside the home are likely to be restricted. Next fall, school schedules may be modified to reduce social density, by having some students come earlier or later in the day or spend some days at home learning on-line. Who will be on-call to supervise them?

From this perspective, consider some of the fascinating findings from on online survey of U.S. parents in mid-April reported in a recent briefing paper published by the Council on Contemporary Families (CCF). This survey was not based on a random sample (which would be hard to accomplish in a short time frame) and relied on stylized questions regarding time spent in specific activities.

The good news is that surveyed that mothers and fathers agree that fathers began doing more housework and childcare after the onset of the pandemic. This does not surprise me too much, since more men were at home, whether as a result of furlough, unemployment, or ability to telecommute. Like the authors of the paper, I’m hopeful that the experience of spending more time in proximity to kids will increase paternal engagement in the future.

The more striking finding, it seems to me, is that the pandemic did not increase time in domestic labor because some tasks like transporting children, attending children’s events, organizing children’s schedules/activities, and grocery shopping became less frequent.

This implies that time devoted to childcare activities declined even as on-call responsibilitiesincreased.

We need to know more about how parents experienced the intensification of such responsibilities. The CCF report is optimistic that the increased opportunities to perform paid work from home will promote a more egalitarian gender division of labor. I’m not so sure that paid work at home is viable for parents of young children without some delegation of supervisory responsibilities.

The CCF report devotes substantial attention to differences in mothers’ and fathers’ tallies of the way in which domestic responsibilities are allocated, an issue also highlighted by a recent surveys conducted by the New York Times and USA Today. These discrepancies highlight the greatest shortcoming of surveys based on stylized questions—women and men probably interpret questions differently, and reporting of relative participation (as in, who does more than whom) is particularly susceptible to social desirability bias.

Diary-based surveys—even if greatly abbreviated and simplified– would almost certainly yield more accurate results, especially if they included explicit attention to on-call responsibilities. Yet some additional stylized questions—especially about perceptions of supervisory constraints and the experience of doing paid work at home with young children present—would also be super helpful.

* I wish the ATUS also asked how much time sick or frail family members were “in your care” but it does not; nor is it clear how accurate responses to this question regarding children under the age of 13 are.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on May 27th, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Policy Briefs & Reports, Time Use Survey

A Gender Lens on COVID-19: Investing in Nurses and Other Frontline Health Workers to Improve Health Systems

In a recent CGD blog post, author Megan O’Donnell highlighted seven areas where long-run, gender-responsive thinking can help to insulate against the consequences of pandemics like COVID-19 and their disproportionate impacts on women and girls. Here we take a deeper dive into one of those areas: the promotion of a gender-equal global health workforce in which the occupations where women predominate, such as nursing and community health work, are valued, prioritized, and properly resourced.

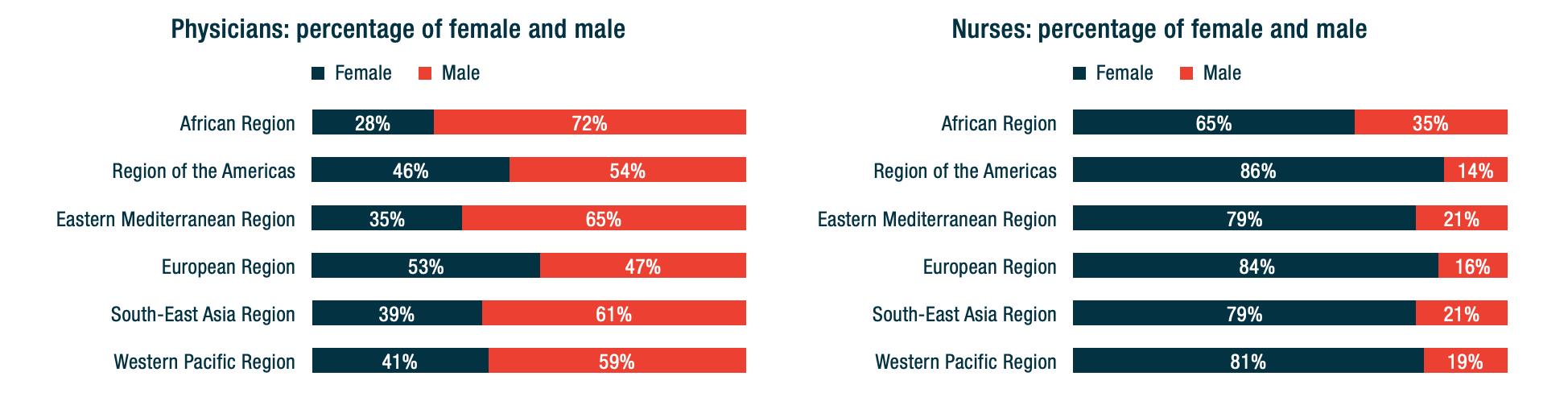

Worldwide, women make up anywhere from 65 percent (Africa) to 86 percent (Americas) of the nursing workforce. Their jobs are critical to the health, safety, and security of communities on any given day, and particularly in times of a global pandemic. And yet, more obviously now than ever before, we face a global nursing shortage. To address this critical short fall and ensure sufficient numbers and distribution of health workers to provide both emergency and routine care in time of crisis, governments need to increase and improve their long-term investment in nurses, including by addressing gender gaps in the health workforce.

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities, Healthcare

How Will COVID-19 Affect Women and Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries?

Policymakers should be thinking—and worried—about how COVID-19 is expected to disproportionately affect women and girls. Gender inequality can come into even starker focus in the context of health emergencies. With COVID-19 continuing to spread, what do we see so far—and what can we expect in the future—in terms of the impacts on women and girls?

Wenham, Smith, and Morgan discuss gendered impacts in their article, “COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak,” in the Lancet. Women appear to be less likely to die from COVID-19: “Emerging evidence suggests that more men than women are dying, potentially due to sex-based immunological or gendered differences, such as patterns and prevalence of smoking.” But keep in mind that “current sex-disaggregated data are incomplete, cautioning against early assumptions.” In other research, data from 1,000+ patients in China show that “41.9% of the patients were female.” (Guan and others 2020). But beyond these direct effects, most of the other impacts affect women negatively and disproportionately.

Wenham, Smith, and Morgan highlight that women will be more affected in places with more female health workers. In an analysis of 104 countries, Boniol and others (2019) show that women form 67 percent of the health workforce (see the figure below). In China, “an estimated 3000 health care workers have been infected and at least 22 have died” (Adams and Walls 2020). As the pandemic spreads, the toll on women health workers will likely be significant.

Figure. Gender distribution of health workers across 104 countries

Source: Boniol and others (2019)

Here are other areas highlighted by Wenham, Smith, and Morgan:

– School closures are likely to have a differential impact on women, who in many societies take principal responsibility for children. Women’s participation in work outside the home is likely to fall. (My colleagues Minardi, Hares, and Crawfurd have written about other impacts of school closures during an epidemic.)

-Travel restrictions will affect female foreign domestic workers. Of course, they also affect male migrants. The distribution will vary by country. Research by Korkoya and Wreh (2015) found that 70 percent of small-scale traders in Liberia are women, so domestic travel restrictions during the Ebola outbreak disproportionately affected women.

-Health resources normally dedicated to reproductive health go towards emergency response. During the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, for example, the “decrease in utilization of life-saving health services translates to 3600 additional maternal, neonatal and stillbirth deaths in the year 2014-15 under the most conservative scenario” (Sochas, Channon, and Nam 2017). In my own research (with Goldstein and Popova), we found that the disproportionate loss of health workers in areas that had few to begin with would likely lead to higher maternal mortality for years to come.

-When women have less decision-making power than men, either in households or in government, then women’s needs during an epidemic are less likely to be met.

Here are four additional concerns:

-Sexual health: During the school closures of Sierra Leone’s Ebola outbreak, “a reported increase in adolescent pregnancies during the outbreak has been attributed largely to the closure of schools.” (UNDP 2015). Bandiera and others find that in villages highly disrupted by Ebola, girls were “10.7 percentage points more likely to be become pregnant, with most of these pregnancies occurring out of wedlock.” A United Nations report gives an even higher estimate of 65 percent. The absorption of health resources by emergency response may also lead to disruptions in access to reproductive health services.

Many girls didn’t return to schools once they reopened, and there were increases in unwanted sex and transactional sex. (Notably, Bandiera and others also find that girls in villages where there were established “girls’ clubs”—safe spaces for teenage and young adult girls to gather and get job and life skills—before the epidemic experienced fewer of these adverse effects.)

-Intimate partner violence rises in the wake of emergencies: Parkinson and Clare document a 53 percent rise in the wake of an earthquake in New Zealand and nearly a doubling in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in the United States. Mobarak and Ramos find that in Bangladesh, increased seasonal migration reduces intimate partner violence, at least in part because women spend less time with the potential perpetrators of that violence. Travel restrictions may be expected to have the opposite effect.

-The burden of care usually falls on women—not just for children in the face of school closures, but also for extended family members. As family members fall ill, women are more likely to provide care for them (as documented during an Ebola outbreak in Liberia, with AIDS patients in Uganda, and in many other places), putting themselves at higher risk of exposure as well as sacrificing their time. Women are also more likely to be burdened with household tasks, which increase with more people staying at home during a quarantine.

-As Mead Over and I have discussed, health crises can trigger economic crises. Economic crises affect women disproportionately, particularly in low-income countries. Sabarwal and others found that men’s labor force participation remained largely unchanged during economic crises, whereas women’s labor force participation rose in the poorest households and fell in richer households.

-Last week, the World Health Organization declared that “this is the first pandemic caused by a coronavirus.” There have been more than 168,000 confirmed cases and more than 6,600 deaths in 148 countries as of publication of this blog. The impact of this pandemic will be felt for years to come. As women are often disproportionately affected by the follow-on effects of the disease, we have to make sure that we keep women’s rights and needs front and center in our responses. A first step in doing that is making sure that women are a central part of the teams designing those responses.

Contributed by David Evans, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, working on education, health, and social safety nets.

This post benefitted from comments provided by Susannah Hares, Megan O’Donnell, Emily Christensen Rand, and Rachel Silverman.

Original blog published on Center for Global Development website March 16, 2020, see here for the original posting

Reposted with permission from David Evans, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development

- Published in COVID 19, Healthcare

The Homemade Value-Added Stabilizer

“Shelter in place” mandates in the early stages of the U.S. Covid-19 pandemic required many people to stay home, cook their own meals, school their own children, and entertain themselves. Unpaid work served not only as a social safety net, but also as an automatic stabilizer. While it didn’t dampen fluctuations in official Gross Domestic Product, as did unemployment insurance, it clearly helped stabilize consumption.

Just imagine what would have happened if most people had not had refrigerators, stoves, and computers—or just read reports of the plight of homeless people.

By mid-March 2020, many states and localities shut down restaurants for any services other than take-out. Home-produced meals increased of necessity. Many such meals probably consisted of convenient processed foods that could be popped into a microwave oven, but a renaissance of home cooking also became apparent, along with reliance on long-lasting, easily stored items such as rice and beans. Analysis of Google Search terms showed a sharp spike in questions concerning food preparation and storage. As one newspaper put it, America began baking its heart out. Yeast suddenly became as hard to come by as toilet paper.

In 2018, according to the American Time Use Survey, adult civilian women spent an average of .8 hours a day, and their male counterparts .4 hours a day in meal preparation. How much more did they spend in the months of March and April, and what was the monetary value of this unpaid labor, based on what it would have cost them to hire someone to plan, cook, and clean up? How much did they save on eating-out?

Many childcare centers and schools were closed, leaving parents with responsibility for home-schooling, supervising children, and keeping them from going confinement-crazy. The American Time Use Survey averaged the amount of reported time that married mothers and fathers living with children under the age of 18 spent in primary activities of caring for and helping household children over the 2013-2017 period—an average of 2.6 hours per day for mothers not employed and 1.4 hours for fathers not employed.

Under sequestration, both active care and supervisory care (defined as the time in which an adult reported that a child under the age of 13 “in their care” ) ballooned. How much did these two forms of childcare increase? How much did households save on childcare costs?

Video streaming and gaming increased dramatically, especially during afternoon hours, and people began to rely more heavily on streaming for instruction and exercise as well as entertainment. So, while they spent less money (and less travel time) on entertainment away from home, they substituted forms of entertainment that were probably less expensive, on average. How much less expensive?

Between March and May, average household income plummeted as a result of job furloughs and unemployment. The increase in time devoted to household production buffered this loss to some extent—but without answers to the questions above, we can’t know how much. Most recent impromptu household surveys have focused primarily on women’s unpaid work relative to men’s—an important, but different topic.

For years, I have protested economists’ lack of interest in total consumption—defined as the sum of money expenditures and the consumption of home-produced services.

Let me will repeat one example that I have written about in more detail elsewhere: Compare two couples, each with two small children, each earning $50,000 after taxes. Conventional measures treat them as having exactly the same income. Yet one couple may include an adult earning $50,000 and a full-time homemaker/caregiver, while the other includes two adults earning $25,000 each and obviously has less time to devote to unpaid work. If we assigned any positive value to unpaid work, the first household would obviously be better off in terms of both income and consumption.

Market income is just not a very good indicator of total consumption among households with differing inputs of unpaid work. Also, the value of unpaid work is greater in households with more than one person, because of economies of scale in food preparation and childcare. Standard equivalence scales used to adjust household income for household size and composition completely ignore these issues.

Obviously, the additional unpaid work performed while sheltering in place was a source of great stress, especially for those simultaneously telecommuting, zooming, or otherwise trying to fulfill paid employment responsibilities at home. Yet, it’s hard to deny that this work also “added value,” enabling an important form of social provisioning.

The worst-case scenario for a household with children was almost certainly one in which all adults (e.g. mother and father) were essential workers, required to keep working (often at risk to their health) but unable to work from home. Federal and state agencies tried to provide “resources” for these workers, but no guarantees were forthcoming.

In many cases, one of the adults (probably the mother) was forced to quit or take a leave of absence from paid employment. While new federal legislation gives states flexibility to pay benefits where an individual leaves employment to care for a family member, not all states do so.

Such a policy is effectively a paid family leave—something that most states have shied away from for years, making this country an international outlier. The complexity of the new legislation, plus the difficulty of actually filing for and receiving unemployment benefits, has probably kept take-up pretty low even in states that allow this option.

Just one more reason to consider policies such as federal paid family and sick leaves and a universal basic income that could help the stabilizers known as households do their job.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on May 19th, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in COVID 19, Time Use Survey, U.S., Unpaid Work

Playing the Long Game: How a Gender Lens Can Mitigate Harm Caused by Pandemics

When crisis hits, longer-term thinking can easily, and understandably, be cast as a distraction or a luxury—even when it relates to tackling critical issues like gender inequality, climate change, or extreme poverty.

Speaking personally, I’ve felt a bit silly trying to push forward projects that focus on gender lens investing or women’s economic empowerment in the last few weeks, given that my colleagues’ and collaborators’ attention, and frankly much of my own, lies elsewhere, and with something that seems much more pressing.

But for those of us who are in the position of privilege to continue thinking long term, it’s our responsibility to do so. Working towards structural changes that will take longer to come to fruition, especially those that relate to reducing global inequality, is the only way to radically decrease the extent of harm caused by moments of crisis, especially for vulnerable populations.

Dismantling unequal power structures, and in turn ensuring that every individual—regardless of gender, age, income level, national origin, and so on—has a safety net protecting them from vulnerability to health scares, income loss, and threats of increased violence, will allow us to focus on crisis without fearing fallout across every dimension of life.

In times of pandemic, the economically vulnerable cannot afford to stay home. Women in quarantine are facing increased risks of intimate partner violence. Girls staying home from school in some parts of the world may not have the opportunity to return. And none of this would be the case if we more effectively tackled the forms of inequality that underlie these realities. Then a virus could be a virus — assuredly deadly and destructive from a health perspective – but without inciting increased abuse, poverty, and lost prospects.

My colleague David Evans, drawing upon work by Claire Wenham, Julia Smith, and Rosemary Morgan in The Lancet, recently highlighted a range of problems stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic that disproportionately impact women and girls. In hopes of continuing to move the conversation forward, I propose some solutions to those problems here, and welcome others to add to this initial list. To be clear, these actions should not distract from immediate measures to address the pandemic. But we also can’t afford to risk forgetting about them when the focus on COVID-19 has faded; otherwise history is doomed to repeat itself.

1. Promote a Gender-Equal Health Workforce

Because the health workforce is disproportionately women (67%), women are at a higher risk of exposure to the virus within medical facilities.

More doctors worldwide are still men. But the vast majority of the global health workforce consists of nurses, community health workers, and others who are less highly compensated. All health workforce jobs need to become increasingly well-compensated, high-quality jobs. Not only will this incentivize men to seek these positions, destigmatizing their current positioning as “feminine” and dismantling occupational sex segregation within the healthcare sector, but it will also ensure that those on the frontlines of protecting populations from pandemics don’t also have to fear economic fallout on a day-to-day basis.

The number of women doctors is rising. Research from other sectors tells us what works to combat occupational sex segregation, including men acting as mentors supporting women to “cross over” into higher-paying occupations. These efforts will have to be paired with those that increase the perceived (and actual) value of work in sectors, including nursing and other frontline health work, where women dominate. More research is needed on this front, both on what works to incentivize men to take up traditionally “feminine” roles and how to avoid unintended displacement of women from those occupations.

2. Protect (and Expand) Existing Health Resources

With all hands on deck to fight COVID-19, particular groups of women and girls face other health risks.

Health facilities should not have to choose between providing lifesaving care in the face of pandemics and continuing to provide support for those in need in other areas, including pregnant women, adolescent girls (who have the highest prevalence of HIV infection, and in need of life-saving medication to keep their immune systems strong), and all women and girls in need of contraceptive access.

Increased investments in health are needed to ensure critical day-to-day care is not compromised during times of crisis. Establishing a Global Health Security Challenge Fund would help ensure countries are prepared to balance day-to-day needs with additional burdens in the face of pandemic, and evidence-based prioritization strategies are needed for when resources cannot be expanded.

3. Reduce and Redistribute Unpaid Care Work Burdens

As schools close and people fall ill, women and girls will assume increased unpaid care work burdens.

Under business-as-usual scenarios, women and girls do more than their fair share of unpaid care work, which limits their educational attainment, workforce participation and advancement, and leisure time. To lessen these burdens in times of crisis and more generally, we need increased investments in child and elder care, and in the poorest countries, gender-responsive energy, water, and sanitation infrastructure that would reduce the time women and girls must spend collecting water and fuel, as well as cooking and cleaning. We also need shifts in household norms that mean men assume more unpaid care responsibilities. Initiatives focused on promoting women’s economic empowerment, such as 2X Challenge and the Women’s Global Development and Prosperity (W-GDP) initiative, as well broader investments in gender equality and economic growth, must prioritize reducing and redistributing women and girls’ unpaid care work.

4. Address Gender-Based Violence

With quarantine measures imposed and stress heightened, women are at increased risk of violence committed by their partners and family members, and essential support services are absent.

Early reports suggest that gender-based violence rates are increasing in light of COVID-19 quarantining, consistent with evidence documenting increased violence in other crisis settings. Gender-based violence needs to be elevated as its own public health crisis, and resourced accordingly.

We’re far from meeting this objective, considering that all OECD donors combined allocated less than $200 million to addressing violence against women according to 2016-17 data, and over half of this financing came from just three countries (Australia, Canada, and Norway). Increased resources should target evidence-based approaches, such as Promundo’s MenCare program.

In pandemic contexts, preparations for social distancing should include considerations of how individuals will be able to access social services when faced with violence in their households. The World Bank has taken a step in the right direction in positioning interpersonal and gender-based violence as priorities to address in its new Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Strategy, though time will tell how the bank and other donor institutions finance this priority.

5. Guarantee Girls’ Education

With schools closing as part of social distancing measures, girls who already face pressure to drop out of school may not return.

Even absent crisis, tens of millions of girls globally face pressures to drop out of school to care for siblings and do other unpaid domestic work, contribute to supporting their households financially, and/or marry and have children when they are still children themselves. These pressures may be heightened due to interruptions in their education, as observed when Ebola hit West Africa. School closures, especially those impacting adolescent girls, should be weighed against longer-term risks related to girls’ school drop-out and limited school-to-work transition prospects as a result. Where possible, efforts should be made to incentivize parents to allow their children to return to school and to ensure consistent access to sexual and reproductive health services in the interim, as unintended pregnancy is cited as a reason for girls’ failure to return to school.

6. Promote Women’s Economic Opportunities

Across the globe, women are more likely to work jobs that are low-paid, informal, and lacking in benefits.

In large part due to the disproportionate unpaid care work women take on, they are less likely to be employed full-time, in the formal workforce, or in jobs that provide paid sick leave, unemployment insurance, and other protections.

We must continue to invest in evidence-based programs and policies that improve women’s economic opportunities and support organizations such as the Self-Employed Women’s Association and Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing—organizations that are well-positioned to provide and advocate for dignified work.

Cash transfers should be considered as a means of ensuring a social safety net for those most in need. Critical to transfers’ success will be (1) ensuring that delivery mechanisms (through digital technology or otherwise) are properly designed and implemented and (2) that those in need, including low-income populations and workers vulnerable to economic backslides because of the virus, are prioritized.

7. Ensure Women’s Representation in Decision-Making and Critical Research

Women are not equally represented in decision-making roles responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force is over 90 percent men, and the team Prime Minister Johnson just assembled to lead the United Kingdom’s COVID-19 response is all men. As in the contexts of peace and security, international trade, and climate change, an exclusionary approach to decision-making will yield inferior decisions: those that don’t account for the needs and constraints of populations absent from the table.

Going forward, decision-making teams should be equally representative of men and women, and also prioritize other forms of inclusion, such as those based on race and ethnicity, as called for by Women in Global Health’s Operation 50/50 campaign.

Women must also be equally represented in clinical trials as biomedical treatments and other interventions are developed. As my colleague Carleigh Krubiner has noted speaking to the context of Ebola, women who are pregnant or breastfeeding are typically excluded from experimental studies, and in some high-fertility contexts, this means up to 80 percent of reproductive age women are virtually invisible in trial samples. Lack of representation means a lack of essential data on the types of prevention methods, treatments, and other interventions that work for women, risking higher fatality rates and other complications.

Times of crisis magnify the cracks in our systems and highlight disproportionate risks to the most vulnerable among us. COVID-19’s impacts, those already felt as well as those still anticipated, should serve as a wake-up call. They should spur action to address underlying inequalities, including those that disadvantage women and girls worldwide and make the consequences of a pandemic even worse than they would otherwise be. Increased prioritization of women and girls’ health, education, economic opportunity, safety, and decision-making power can help create a world where no one falls through the cracks. Decision-makers should realize this is inextricably linked to today’s pandemic response.

Contributed by Megan O’Donnell Assistant Director, Gender Program and Senior Policy Analyst at Center for Global Development

Original blog published on Center for Global Development website March 18, 2020, see here for the original post

Reposted with permission from Megan O’Donnell Assistant Director, Gender Program and Senior Policy Analyst at Center for Global Development

- Published in COVID 19, Gender-Equal Economy, Healthcare

Invisible Frontliners: Migrant Care Workers in the Time of COVID-19

The Covid-19 pandemic has exposed fault lines in national healthcare and social protection systems that have made many countries – developed as well as developing – unable to quickly and efficiently deal with this new health crisis and its disastrous consequences on jobs and incomes. One segment of the population in Europe, North America and Asia’s wealthy countries is falling deep into these crevasses, and, sadly, is missing from national debates and policy agendas on the Covid-19 crisis. This group comprises the migrant care workers, especially those who provide care services to elderly, frail, and dependent persons in caregiving institutions and private homes.

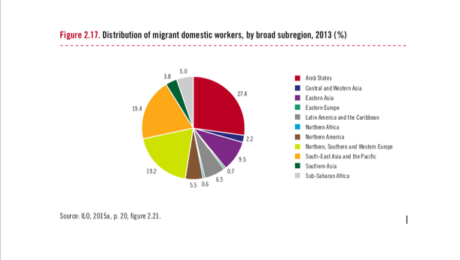

Overwhelmingly consisting of women, these migrant workers (along with minority ethnic groups) are the backbone of the childcare, elderly care and long-term care sectors. They include “nannies”, “home carers”, “social care workers”, “collaboratrice familiar”, nurses and nursing aides, among others. According to the European Commission, workers engaged in “personal and household services” are mostly women, working mainly part-time and often of migrant background. ILO estimates that globally there are 11.5 million international migrant domestic workers, and nearly 80 percent of them are employed in OECD countries. According to data on OECD countries, in 2012–13 28 percent of home-based caregivers were foreign-born.

Increasingly restrictive immigration controls in high-income countries in the past two decades have channelled a disproportionate share of immigrants into jobs in informal long-term and home-based care where wages are low, work hours are long and unpredictable, protection from abuse may be missing, and workload is heavy.[1] These are jobs that can easily be concealed from government surveillance. In the US, UK and Canada, for example, most foreign-born care workers enter the country through non-employment routes, such as family unification, refugee protection and asylum programs, and are on student, tourist and working holiday visas. An unknown number of them work clandestinely.

These migrant care workers are particularly vulnerable in the current Covid-19 pandemic for several reasons. First, eldercare homes across Europe and North America have emerged as hotspots of COVID-19 cases and account for a disproportionate share of deaths related to COVID-19. Data collated by the International Long-term Care Policy Network (hosted by the London School of Economics) across five European countries suggest that between 42 and 57 percent of deaths related to COVID-19 have so far occurred in nursing homes.

Secondly, the disproportionate and increasing share of COVID-19 deaths in eldercare homes is not simply due to the residents’ higher vulnerability due to their age and health conditions. It is also because many caregivers in these homes lack access to PPEs and are often overworked in often understaffed facilities. Being poorly paid, some of them also work in multiple facilities just to make ends meet. Poor working conditions of migrant workers in long-term and eldercare homes have been well documented by several studies – conditions regarding their work hours, allocation of responsibilities for diverse tasks and more difficult patients, low pay rates, and no overtime compensation.

Thirdly, the hundreds of thousands of migrant domestic workers who work in private homes are in the frontlines of keeping homes safe and clean. They face multiple risks as a result of the pandemic – health risks, more demands on their time, and income loss. According to the International Domestic Workers Federation, domestic workers worldwide have reported many concerns since the global pandemic began. With entire families staying home all day due to quarantine measures, domestic workers face heavier demands of cooking, cleaning, and caregiving without the benefit of additional pay for longer hours—and because of mobility restrictions, many cannot leave the homes where they work.

Finally, many care workers who have irregular migrant and/or employment status under informal arrangements have no access to unemployment and health insurance benefits, relief packages or financial aid related to COVID-19. This has been recently documented by the National Domestic Workers Alliance and the Pennsylvania Domestic Workers Alliance (networks representing nannies, caregivers and domestic workers in the US), the European Trade Union, and the Kanlungan Filipino Consortium in the UK. Those who fall ill prefer not to go to hospitals until it is too late for fear of being reported to migration authorities and because they do not have health insurance. These care frontliners are largely invisible and likely to suffer in silence

Contributed by Amy King-Dejardin, Former senior staff of ILO (Geneva) and author of the 2018 ILO report, “The Social Construction of Migrant Care Work.”

[1] King-Dejardin, A., 2019, The social construction of migrant care work, Geneva: ILO https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-migration/publications/WCMS_674622/lang–en/index.htm

*Learn more about the ILO Bureau of Gender Equality here

- Published in COVID 19, Migrant Care Workers