The Unpaid Care Work and the Labor Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys

How much time do people spend on doing paid and unpaid care work? How do women and men spend their time differently on unpaid care work? Are there any differences in time use among the regions? How do socioeconomic factors influence people’s choices to do paid and unpaid care work?

Jacques Charmes addresses these questions in recent ILO report by providing a comprehensive overview of the extent, characteristics and historical trends of unpaid care work. The report is based on the analysis of the most recent time-use surveys carried out at the national level across the world, revealing the differences in time spent on unpaid care work between women and men and among people with different socioeconomic characteristics, such as geographical location, age and income groups, education level, marital status and the presence and age of children in the household. An insightful discussion of the concepts and methodological approaches underlying the analysis of time-use data is also offered.

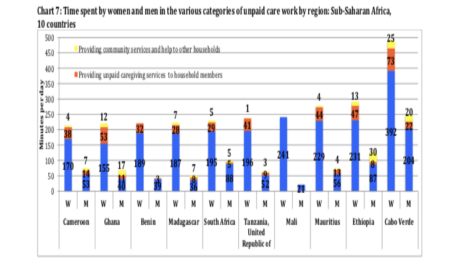

Chart 7 in the ILO Working Paper the Unpaid Care Work and the Labour Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys illustrates the time spent by women and men in various categories of unpaid care work across Sub-Saharan African countries including Cameron, Ghana, Benin, Madagascar, South Africa, Tanzania, Mali, Mauritius, Ethiopia and Cabo Verde. As with the case around the world, women in Sub-Saharan African countries are providing significantly more unpaid care services in households and communities. Read the report to learn more about time-use analysis concepts and methodologies, gender variations in paid and unpaid work across the world and across various socio-economic levels:

International Labour Organization

Gender, Equality and Diversity & ILOAIDS Branch

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy Briefs & Reports

Responsibility Time

If there was ever a time we urgently needed to know more about time use, that time has come. The Covid-19 pandemic utterly changed daily rhythms for many sequestered households and the “opening up” process closed down some old routines.

I’ve done extensive work with time use data, have been in touch with several people/groups trying to measure the impact of the pandemic, and am trying to follow results being reported in other research.

My reactions are conditioned by long-standing concerns about survey methodology.

It is surprisingly hard to get an accurate picture of how people use time, because we all tend to do more than one thing at once. Also, doing is not the whole story—being present, available, on-call, and taking responsibility for others is typically far more time-consuming than specific acts of helping. This is especially true for the care of young children, people who are sick, frail, or suffering a disability.

Sheltering-in-place guidelines, combined with the social distancing, have probably had a much bigger impact on where people are, who they are with, and what they are responsible for—than on their activities.

Yet most surveys focus on activities alone, in several variations. They ask stylized questions about how much time people spent in various activities in a given time period, such as the previous day. Or, they persuade respondents to fill out a time diary in which they report what they did in specific intervals (such as every ten minutes) between waking up in the morning and going to sleep at night.

Note the prominence of the words “activities” and “doing” in both cases. Some surveys reach a bit further. The annual American Time Use Survey (ATUS), for instance, asks people if a child under the age of 13 was “in their care” while they engaged in activities. While the ATUS describes such care as a “secondary activity,” it is better interpreted as a responsibility that strongly influences the way that people organize their activities and plan their schedules.

Being on-call to provide care also creates vulnerability to brief but sometimes incessant interruptions whose impact is probably difficult to measure.

This is important because sheltering in place and sequestration almost certainly increased supervisory demands as much (if not more than) active care of young children. At the same time, social distancing guidelines limited peoples’ ability to provide any supervisory care or assistance to elderly or hospitalized family members.

Furthermore, these constraints are likely to be in place for some time—over the summer, children’s activities outside the home are likely to be restricted. Next fall, school schedules may be modified to reduce social density, by having some students come earlier or later in the day or spend some days at home learning on-line. Who will be on-call to supervise them?

From this perspective, consider some of the fascinating findings from on online survey of U.S. parents in mid-April reported in a recent briefing paper published by the Council on Contemporary Families (CCF). This survey was not based on a random sample (which would be hard to accomplish in a short time frame) and relied on stylized questions regarding time spent in specific activities.

The good news is that surveyed that mothers and fathers agree that fathers began doing more housework and childcare after the onset of the pandemic. This does not surprise me too much, since more men were at home, whether as a result of furlough, unemployment, or ability to telecommute. Like the authors of the paper, I’m hopeful that the experience of spending more time in proximity to kids will increase paternal engagement in the future.

The more striking finding, it seems to me, is that the pandemic did not increase time in domestic labor because some tasks like transporting children, attending children’s events, organizing children’s schedules/activities, and grocery shopping became less frequent.

This implies that time devoted to childcare activities declined even as on-call responsibilitiesincreased.

We need to know more about how parents experienced the intensification of such responsibilities. The CCF report is optimistic that the increased opportunities to perform paid work from home will promote a more egalitarian gender division of labor. I’m not so sure that paid work at home is viable for parents of young children without some delegation of supervisory responsibilities.

The CCF report devotes substantial attention to differences in mothers’ and fathers’ tallies of the way in which domestic responsibilities are allocated, an issue also highlighted by a recent surveys conducted by the New York Times and USA Today. These discrepancies highlight the greatest shortcoming of surveys based on stylized questions—women and men probably interpret questions differently, and reporting of relative participation (as in, who does more than whom) is particularly susceptible to social desirability bias.

Diary-based surveys—even if greatly abbreviated and simplified– would almost certainly yield more accurate results, especially if they included explicit attention to on-call responsibilities. Yet some additional stylized questions—especially about perceptions of supervisory constraints and the experience of doing paid work at home with young children present—would also be super helpful.

* I wish the ATUS also asked how much time sick or frail family members were “in your care” but it does not; nor is it clear how accurate responses to this question regarding children under the age of 13 are.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on May 27th, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Policy Briefs & Reports, Time Use Survey

Domestic and Care Workers Under COVID-19

By definition, domestic workers are an essential part of the global care workforce. According to the ILO, there are 70 million domestic workers over the age of 15 working directly for private households. They therefore make up roughly 22.7% of the global care workforce (which number 308,6 million).[1] Since its foundation in 2013, the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) has worked with global unions and key audiences with the aim of including home care workers into the global agenda on “care” and to fight for the improvement of their living and working conditions.

Work in the care sector changes rapidly due to aging populations in the west and the more industrialized part of Asia. Financial demands on families who rely on unpaid care work, or the reliance by governments on private and not-for-profit sectors to play an increasing role in providing services. In Asia, most governments deny labour rights and working conditions, particularly for migrant workers, In the west, there is an increasing number of undocumented migrant domestic workers and they do not enjoy labour rights protection due to their vulnerable status. In recognition of the challenges in care work, in 2018 the IDWF Congress adopted two Resolutions (No. 3 & 4) to guide the Federation’s work and address global demands on developing inclusive care systems, special protection programs, and special attention to undocumented and migrant worker’s needs.

The new coronavirus pandemic has impacted all regions for more than three months. Domestic, household and care workers are on the frontlines in keeping families and communities healthy, but they are also most at risk. COVID19 has increased the vulnerability of the sector, which is already and broadly characterized by lack of protections, social security or recognition in many places of the world.

The IDWF consists of 74 affiliates in 57 countries, representing almost 600,000 domestic workers. Since the pandemic began, the IDWF has been actively engaging with affiliates in all regions to monitor the situation on the ground. In many countries, workers are experiencing a substantial increase in workload to ensure cleanliness and hygiene; or in taking care of older people and people with existing medical conditions.

The most critical issues identified:

– Domestic and care workers, especially the live-out/ part time are the most vulnerable group. They cannot move around and lose their jobs due to the lockdowns and social distancing rules, or their employers no longer call them in to work. Many have endured this situation for several weeks while others are losing their jobs with no prospects of finding new sources of income.

-Without income, migrant workers are especially vulnerable as they try to survive in the destination countries. In many countries, migrant workers are not eligible for medical services and hence do not get COVID-19 tests, places for quarantine or medical treatment when needed.

-Workers from rural areas working in the cities, cannot return to their families, or access relief packages provided by local governments.

-The lack of medical and social protections benefits renders domestic and care workers unprotected even when they are sick or need to be quarantined with no remuneration. IDWF and Affiliates are monitoring the mortality rates of members, a difficult task as many governments do not test or report incidents.

-Despite the essential work, domestic and care workers face increasing discrimination during the pandemic. Many workers report for being blamed for bringing the virus into their employers’ homes.

-The ability of domestic workers unions to keep their offices functioning is also compromised during quarantine or semi-quarantine time. Many unions are able to pay for the basic services and provide essential support (i.e. information, food baskets, training) from income previously generated. It is essential that union offices keep operating and maintaining their services for a range of situations that go from unfair dismissals to gender based violence.

In this situation, most organizations have shifted or stopped normal activities. With exception to those in North America and Europe, most organizations are struggling to find ways and means to address emergencies. Some countries have included domestic workers in their relief programs while others have joined hands with allies to demand governments to give out wages /cash, food, masks, sanitizers, places for quarantine. As the pandemic continues, so will the crisis on the ground.

Based on its assessment, the IDWF will continue to do research and collect data to inform advocacy. The IDWF will also set up a solidarity fund to address some of the most critical needs to enable domestic/care workers –and their families– to cope and survive with COVID-19.

[1] ILO (2018), Geneva. Care Work and Care Jobs For the Future of Decent Work.

Contributed by Sofia Trevino, Sustainability Advisor for International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) and the Project Manager for Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO)

Relevant Links:

IDWF: Decent work for Domestic Workers: Eight Good Practices from Asia

In IDWF site, resources on care work (books, articles, websites, audio)

An essay collection on Care economy: Three Years of Collective and Global Learning About Care

ILO Decent Work in the Care Economy

Care Needs and Migration for Domestic Work: Poland and Ukraine

Migrant Domestic Workers: Promoting Occupational Safety and Health

Expanding Social Security to Migrant Domestic Workers

IDWF Resolutions adopted by the 2nd Congress in 2018, Cape Town, South Africa

ILO: Social Protection for Domestic Workers: Key Policy Trends and Statistics

ILO World of Work Magazine: Violence at Work

Decent Work for Domestic Workers: Eight Good Practices from Asia, ILO and IDWF

Why We Care about Care: An Online Moderated Course on Care Economy, UN Women

Research Network of Domestic Workers Rights

WIEGO:

UN High Level Panel Report on Child Care by Rachel Moussié, Deputy Director of WIEGO Social Protection Programme.

Counting the World’s Informal Workers: A Global Snapshot

The ILO – WIEGO policy brief series on childcare for informal workers

Sofia Trevino is the Sustainability Advisor for International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) and the Project Manager for Women in Informal Employment Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO)

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Domestic Workers, Policy Briefs & Reports

Are We All Care Workers Now?

Who, exactly, are care workers, other than the people we need most right now, as the covid-19 pandemic overlays the division of labor with a new division of risk?

I’ve long been an advocate of using the term “care worker” rather than “caregiver” even though the work can be and often is, at least in part, a gift. Because care–whether performed for pay, or not–is at the crux of any sustainable economic system. All work depends on the successful production and maintenance of workers themselves. Yet because this very notion of care-as-work is relatively new, there is little agreement on its exact boundaries.

When I first started pursuing this issue with Paula England, we emphasized hands-on or face-to-face work that develops the capabilities of the care recipient, an essential aspect of the services that health care providers, workers, child care and elder care workers provide. This emphasis could be translated into a specific list of Census-designated occupations, grounding empirical research on the relative pay of care workers that has revealed significant pay penalties for both women and men in such occupations, controlling for many other variables such as education, experience, and unionization.

I liked this broad definition because it spanned paid and unpaid work, low-wage and relatively high-wage occupations, women and men, creating potential for new political alliances. Sociologists initially embraced the definition with some enthusiasm. Not so, economists, and Robert Solow, who attended some meetings of the Russell Sage Foundation Network on Care Work, pushed us for more specificity.

I felt some affinity with Kenneth Arrow’s insistence on the limits of markets and with efficiency-wage theories pointing to the difficulty of monitoring worker productivity, so added another twist to the definition: work in which concern for the welfare of the care recipient is likely to affect the quality of the service provided. In other words, work not performed entirely for money, akin to what some economists have termed “public service motivation” but more…personal.

Still not quite right. Sociologist Mignon Duffy has argued eloquently in Making Care Count that this definition privileges what she calls “nurturant care,” deflecting attention from the drudgery of menial care tasks–the emptying of bed pans, cleaning of toilets, and mopping of floors often performed by the most disempowered members of society. “Dirty” work itself is devalued. Duffy’s work has nudged me to focus more on industry–the economic consequences, for instance, of being employed in health care, education, or social services, regardless of occupation.

The pandemic, however, has pushed me over a cliff, because it is redefining the meaning of “dirty” work–now, any work that increases the risk of exposure to a potentially deadly virus: not just health care, child care, and elder care and unpaid care for family members, but also food services, package delivery, police protection, home repair services, garbage collection…the list goes on. We rely heavily on the motivations of such workers to minimize our own–as well as their own–chances of infection.

The entire sequestration/shelter-in-place/social distancing strategy relies heavily on good will and voluntary compliance. The very invisibility of covid-19 blurs the boundaries between love and money, us and them. The healthy now may later be sick, the sick now may later be dead. When risk is shared, the overlaps between solidarity and self-interest expand.

Yet so many boundaries, however blurry, remain in place. Whether because of who they are or what they do, some workers face much greater risks than others. It’s not enough to cheer them on, to offer them applause or a bit of extra cash.

If we are all care workers now we should do everything in our power to protect our own.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on April 4, 2020. See https://blogs.umass.edu/folbre/

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massechusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, elderly care

A Time for Reflection on Care

The world outside my study is churning and whirling… as it is engulfed with the fast-evolving health situations in communities around the globe. There are many unknowns about the

COVID-19 illness that has spread rapidly in every continent and the presence of uncertainty—big time—has rattled governments, shaken markets, and upended our daily routines, to say the least.

While I join the hundreds of millions of people who constantly check the news online and in newspapers, radio and/or tv, I also take time to pause. These moments allow me to reflect on

what this difficult time that we are all experiencing means and what it says about us—as

individuals, as members of communities, and as citizens of the world.

For one, I find that:

- each individual action has multitudes of rippling effects, large and small, on others;

- the real world oscillates between predictability and unpredictability; it requires each of us to constantly assess the balance between taking caution and taking risk;

- the distinction between self-interest and altruism (promoting others’ interests) becomes more blurred given the pervasive interconnectedness of our lives;

- adaptation and flexibility are vital life skills that we need to have not just now but at all times;

- we have the ability to change as we obtain more information and as conditions around us change; the notion of fixed tastes and preferences is outmoded;

- the skills that we must hone and develop should prepare us not only to live in a competitive world but also to be able to work together, coordinate and cooperate with one another; for the greater good requires collective action.

As the impacts of the COVID-19 spread intensify, there is growing recognition among governments and the public that traditional efforts for dealing with shocks and managing risks through conventional emergency responses are inadequate. Strategic thinking is needed as much as the ability to respond quickly and to take proactive measures. There is an urgent need to build the adaptive capacity and longer-term resilience of communities and societies.

One striking fact about the current global pandemic is its tremendous effect on the care sector. This includes not only the health care systems employing doctors, nurses, aides, and other health professionals but also the unpaid care labor provided by family members, neighbors, and kin.

Many are changing their daily life patterns to provide further assistance and care support for those who are vulnerable such as their parents or grandparents and for those who are self-quarantined. Many more are willing to take the risk of exposure to care for those who have tested positive and are ill but are staying at home because the healthcare system is inadequate, inaccessible, and/or overwhelmed. The shutdown of schools and daycare centers further adds demand for unpaid care. Parents are struggling to care for their children while at the same time trying to tele-work from home.

“How can I write or have meetings with my six-year old around?”

The cloak or mantle that hides the emerging crisis of social reproduction, or the under- provision of care for people who depend on it, is removed. This global pandemic exposes the heavy demand on those who carry the responsibility for providing care for the sick, the young and the frail elderly, the vast majority of whom have been women. It has upended preconceived notions such as: each individual is a ‘Robinson Crusoe’ in families that can find their own solutions to provide care, and that one’s ability to pay should determine who accesses care in the private sector.

The Care Work and the Economy Project joins the efforts of other organizations, research institutions and advocacy groups towards making the care sector visible to policymakers. The heavy care burden that is now being shouldered by health care systems, households, communities and countries throughout the world makes it imperative to bring care work out of statistical shadows and to remove the veil of ignorance in economic policymaking.

Let us hope that this time is truly different and that the jolt brought about by the current pandemic leads to more openness in the academic community and among policymakers towards a paradigm shift and policy change.

March 2020

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, elderly care, Maria Floro, Policy