Inequalities in access to U.S. care services

In the U.S., states and localities are beginning to ease social distancing policies resulting from the pandemic. With many workplaces calling Americans to return to work, the nation’s care services system, what was already broken, is now in dire need of repair or replace.

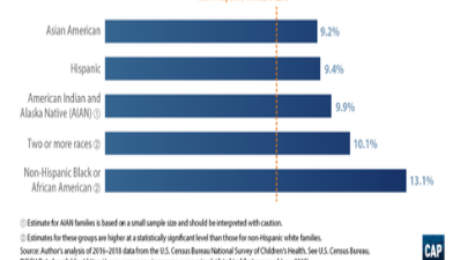

According to a recent analysis by the Center for American Progress (CAP), the lack of adequate child care services in the U.S. negatively affected communities of color before the pandemic, as parents of color were more likely than their non-Hispanic white counterparts to experience child care-related job disruptions that could affect their families’ finances.

The analysis uses the National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH) to show that before the pandemic, Black and multiracial parents experienced child care-related job disruptions—such as quitting a job, not taking a job, or greatly changing their job—due to problems with child care at nearly twice the rate of white parents.

For Black workers and workers of color, decades of occupational and residential segregation has translated to less access to telework, and therefore less flexibility within their responsibilities for young children or elders. In fact, most Black workers and workers of color (especially those who are women) have had to work through the pandemic in essential frontline occupations.

The analysis shows that prior to the pandemic, adequate and affordable child care services was short in supply, particularly for Black, Latinx, and Indigenous families. In fact, more than half of Latinx and American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) families have experiences living in a child care desert – which is an area suffering from an inadequate supply of licensed childcare.

Using child care services as an example, the analysis shows that disparities will likely worsen in the aftermath of the pandemic. A previous CAP analysis estimated that nearly 4.5 million child care slots could disappear permanently as a result of COVID-19, effectively cutting an already inadequate child care supply in half. Recent data suggest that this impact is already being felt, with more than 336,000 child care providers—many of whom are immigrants, African American, or Hispanic—losing their jobs between March and April.

Allowing care services to flounder should not be an option; a broken and inadequate care system would slow the nation’s economic recovery and in addition to deepening existing economic and racial inequalities.

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Race Inequality