Care Arrangement and Caregiving Activities in South Korea: An analysis of 2018 Care Work Family Surveys on Childcare and Eldercare

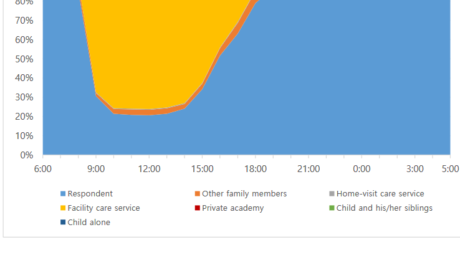

The rise of the care crisis in South Korea has evolved with Korea’s demographic shifts, increasing female work force participation, and changes in the norms and values of family and care over previous decades. Childcare and eldercare, once regarded as women’s typical role within family, are now gaining more social recognition in the public realm. Kang and Eun (2019) examine the nature of, and demand for, caregiving in various areas of the South Korean economy, including family care, care services, childcare and eldercare. The study is based on the nationally representative Care Work Family Surveys on Childcare and Eldercare.

The authors find a significant gap between the number of hours spent on childcare by mothers and fathers. A majority of respondents (women) used at least one external care service. Among caregiving activities, housework such as preparing meals, cleaning, and laundry were reported as the most difficult as well as the most frequently performed activities. Relational and physical activities such as helping to dress, wash, or play with children were reported as less difficult. Caregiving for the elderly can be more complex compared to care arrangements for children, because the range of participants in the family varies. Among all respondents, daughters-in-law were the primary caregiver in the greatest number of cases, followed by daughters, spouses, and sons. Spouses spent the highest number of hours on caregiving, followed by daughter in laws. External care services were not as common for elderly care. Home visit care and home bathing services from the National Long-Term Care program were the most commonly utilized services, although the 3-hour limit per visit amounts to a low amount of total caregiving time. Assisting with bathing and using the restroom was considered especially difficult for the elderly. Housework was performed with the same intensity and frequency in both childcare and eldercare, highlighting the important role it plays in both.

This paper will be available December 2019

This blog was authored by Eunhye Kang and Ki-Soo Eun

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

Measuring the Overall Strain of Caregiving: A Multidimensional Approach

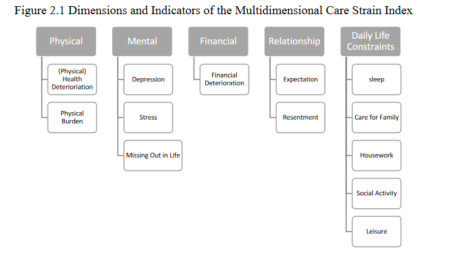

Providing care for others, especially for the frail elderly and young children, is one of the most important forms of human work that sustains our existence. However, caregiving is also often challenging and strenuous. Many informal caregivers are known to suffer negative physical, emotional, and social outcomes, and are at risk of losing their own health and well-being. Fengler and Goodrich, for example, refer to the wives of frail elderly men as ‘the hidden patient,’ warning the negative consequences of caregiving on informal caregivers. Since the 1980s, several instruments have been developed to measure the strain of caregiving among informal caregivers. Some measurements such as the Zarit Burden Interview and the Caregiver Strain Index have been applied more widely, while other measurements have been used for more specific groups of caregivers (e.g., who takes care of the elderly with cancer). Although these measures provide valuable information on various dimensions of caregiver strain, they are not sufficient to assess the overall level of strain experienced by caregivers. In most cases, these measurements consist of a list of questions or statements about the caregiver’s burden; the sum of the answers is then used to indicate the level of burden/strain experienced by the caregiver. Although useful, a simple non-weighted sum of answers may not be an accurate representation of the overall strain. For instance, two groups of caregivers may have the same average total strain score, but one group may consist of all caregivers who suffer strain in some statements, while the other group may have half of the care givers who suffer strain in all statements and the other half who do not suffer strain at all. While the marginal distribution may be the same, the joint distribution may not, and this has an important policy implication.

Adapting the Alkire-Foster method developed to measure multidimensional poverty, Jun et al (2019) propose a threshold-based approach to measuring overall caregiving strain that accounts for the multidimensionality of the caregiving experience. The approach is based on the premise that as in the case of poverty, the negative consequences of multiple strains attached to caregiving would be greater than the sum of their individual effects. The authors first identify the dimensions and indicators that are known to be important consequences of caregiving, such as physical, psychological, financial and relational strains, and daily life constraints. They then count the overlapping strains a care giver experiences under different indicators of caregiver strain. Next, they identify caregivers who are experiencing strains above a specific cut-off point as multi-dimensionally strained. This measure is tested using the data from the newly collected Survey of Eldercare and Childcare in Korea 2018, exploring whether receiving support, help and appreciation may be associated with reduced chance of being multi-dimensionally strained. By providing an overall measurement that identifies caregivers with multiple strains, the authors examine 1) which group of caregivers are more likely to be at risk; 2) which dimensions do most caregivers suffer strain; and 3) what may be potential buffers for caregiving strain.

This paper will be available December 2019

This blog was authored by Jiweon Jun, Ki-Soo Eun and Ito Peng

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

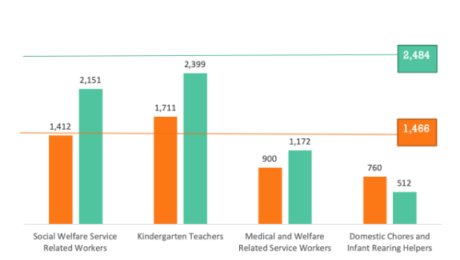

Methodology for Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea

Care work, whether unpaid or paid, lies at the heart of humanitarian concern and expression, and our societies and economies are dependent on it to survive and thrive. Across the world, women account for more than three-quarters of the total amount of unpaid care time while two-thirds of paid care workers are women (Folbre et al. 2012; ILO 2018; Yoon et al. 2011).The outsized role that women play in providing care is readily observed in South Korea, with its strong patriarchal and familistic orientation that assigns primary responsibility for the care of children and elderly to women in the household, reinforcing the economic significance of gender. While unpaid care work by family members, especially women, makes up a large part of the care provided within Korean society, the rapid aging of the population and the fact that more than 50% of the female population aged 16 and older participated in the labor force in 2016-18 underscore the importance of paid care workers in meeting care needs(ILO 2018).They tend to the most basic necessities and help sustain the well-being of those in dependent positions, such as children, frail elderly, or people with illness and/or disabilities. Broadly, there is a spectrum of paid workers providing care, ranging from informal workers such as domestic service workers, nannies, and home care aides in private homes to formal workers in child care centers, nurseries and early childhood learning centers, elder care centers, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities, to nurses and teachers.

Accounting for the contribution of paid care workers is crucial to our understanding of the centrality of care in the development of human capabilities and economic progress; itis a crucial part of the effort to make women’s work and all forms of care work more visible. As the ILO (2018) points out, “care workers close the circle between unpaid care provision and paid work” (p.166). It is also critical to understand their work conditions since they represent one of 5the fastest growing segments of the labor force. For that reason, it is of particular concern that the paid care workforce experience slow wages and difficult working conditions across occupations and industries (ILO 2018). For instance, domestic workers are most vulnerable to exploitation and abuse among all workers in the labor market (UNDP 2015), a consequence of their frequent exclusion from laws and regulations affording labor protections. Understanding paid care work is therefore critical to shedding light on the implications of economic, cultural, and policy contexts that shape the larger labor market as well.

Suh (2019) provides a comprehensive picture of the paid care workforce in South Korea by measuring its size and extrapolating the median wage earnings and aggregate hours spent on care-giving by the workers using following data sources: the Local Area Labor Force Survey, Child Care Statistics, Social Services Voucher Statistics, and Long-term Care Insurance Statistical Yearbook for 2009 and 2014. The size of the paid care workforce in South Korea in this estimation focuses on the value of the labor provided by care workers that are directly and indirectly involved in elder care and childcare provision. The estimation will be used for making the paid care sector visible in the Korean Social Accounting Matrix (SAM), which serves as the base for developing the GAM Care Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model for policy analysis.

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

Methodology for Estimating the Unpaid Care Sector in South Korea

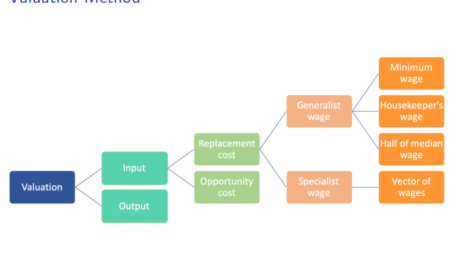

Mainstream economists continue to define economic growth in terms of conventional measures such as market employment and income per capita. Women’s taking on full-time employment outside the home, therefore, has stimulated Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, while the social cost of a shift from informal to the formal economy has been ignored. The importance of fully recognizing the economic contributions of all forms of work –paid and unpaid–as a precondition for achieving gender equality has been proposed by feminist researchers since 1980s (Waring 1988, Folbre 1991). They have emphasized the need for empirical analysis of time devoted to unpaid care work, especially direct care of children, adults in need of assistance because of illness or disability, and the frail elderly.

Unpaid care work, i.e. household production, is the most significant part of production which is excluded from the production boundary of the system of national accounts(SNA) and hence, from the most commonly used economic indicator, Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The failure to recognize the economic value of unpaid care work leads to the belief that people who, without compensation, devote time to caring for others are unproductive or inactive and their unpaid activities fall outside the business of economic life. To be sure, unpaid household services and care work are now recognized in the landmark resolution for defining and measuring work passed during the 19th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) in 2013. Nevertheless, the lack of recognition of unpaid care work in the national accounts hinders the promotion of gender equality at the macroeconomic level due to the importance of these accounts as instruments for policymaking.

Suh (2019) first explores the concept of unpaid care work and its two forms, direct or relational care activities and indirect care activities. It then examines the role of time use data in estimating the unpaid, direct or relational care labor time provided by household members and the various methods by which this form of unpaid care work can be measured and valued, highlighting methodological and measurement issues. The input-based approach is then applied to the estimation of the imputed value of unpaid care provided by women and men aged 18 years and older based on the national Korean time use survey data and the Korean Labor Force survey for 2009and 2014. A range of wage rates is used for the estimation and differences between women and men are highlighted. These estimates are then aggregated for the population of South Korea. Finally, the paper concludes with a brief commentary on the importance of measuring and valuing unpaid care work.

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

An Overview of Care Policies and the Status of Care Workers in South Korea

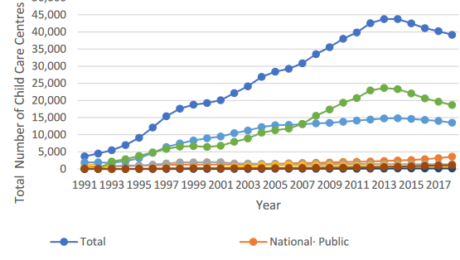

The last couple of decades have seen a dramatic transformation of the care infrastructure in South Korea. This is evident from the introductions of successive government policies and programs to socialize care and to address the issue of work-family balance. These new policies and programs have resulted in a steady expansion of publicly funded and publicly or privately provided care services for children and the elderly, financial support for families with young children, and family support programs such as maternity and parental leaves and family care leaves. Although there has been a significant amount of research on child and elder care policies in Korea, not as much attention has been paid to the status of care workers. This is unfortunate particularly given that social care expansion in Korea has been one of the most important drivers of employment growth in the country for the last decade and a half.

Peng et al (2019) provide an overview of care policies in South Korea and their developments since 2000 and discuss the status of care workers in the context of the current care infrastructure. They focus on paid childcare and elderly care as much of the country’s current care policies are directed to these two sectors. A broad overview outlines the current care policies and systems, including some data on the number of people who are affected and serviced, and some of the immediate causes of the government’s policy focus on care and of social care expansions and reforms. Recent developments in Korea’s care policies illustrate a path of progressive and successful socialization of care that has yielded a significant employment generation, particularly for women. Despite the progress in social care, however, available data suggest that the working conditions and status of care workers in Korea are not very positive: women dominate care work in both child care and elder care, and care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and their employment is precarious. Care work is also accorded with low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress.

The authors conclude by discussing the implications of South Korea’s current care infrastructure for gender equality and the care economy. To better understand the nature of care work and the status and situations of care workers, and Korea’s care infrastructure, they call for more in-depth data collection on care workers as well as more comprehensive measures of care

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

Policy Analysis in a Macroeconomic Model of Social Reproduction

Since the 1990s, unpaid work and care have garnered increasing academic attention, creating the emerging fields of the economics of unpaid work and the study of “the care economy.” Most of the earlier work was oriented toward microeconomics, focusing on issues such as the household division of labor, subsistence production in developing countries, the substitution between non-market and market goods and services in households, and the role of caring motivations in sectors of the labor market in developed and developing countries. Empirical work paralleled these theoretical efforts. Examples include measuring unpaid work via time-use surveys across the world, estimating the monetary value or opportunity cost of unpaid work, and linking care with the gender–wage gap and gendered job segregation. Macroeconomic models exploring gender and economic development were rare, and even fewer macro studies examined care and unpaid work.

Braunstein et al. (2011) contributed to this literature by embedding unpaid work and care in a structuralist macro model, illustrating how the social structures of production matter for economic outcomes. Braunstein and Tavani (2019) recast a simplified version this model in order to generate policy implications through numerical simulation. The authors go beyond the standard utilization-labor share framing in structuralist models in order to focus on more direct measures of gender inequality and the gender composition of the labor force and of employment. The resulting producer’s equilibrium – which describes the supply side of the model – always features a positive relationship between economic activity and gender wage equality. The goods market equilibrium, or the investment-savings curve, can either be care-led or inequality-led. The model results accommodate a variety of scenarios. A reduction in non-market care time can foster both aggregate demand and gender equality, but under some conditions it is also possible that there are trade-offs between economic activity and gender equality.

This paper will be available in December 2019.

Informal Caregiving, Family Power Dynamics, and Labor Market Rigidities

A growing concern in many countries is an aging population and an increase in the number of elderly in need of long-term care (LTC). However, the economic and welfare implications of LTC provision remain relatively understudied. One of the primary factors which complicates welfare analysis is that a bulk of elderly care is provided by family members. Norton (2000) estimates that roughly two-thirds of LTC is provided informally. The pervasiveness of informal care due to cultural or family ties has even limited the development of LTC insurance in economically advanced regions like Europe (Costa-Font, 2010). Hence, in order to understand the full macroeconomic implications of growing LTC demands and the appropriate policy response, it is imperative to explore how households cope with these caregiving needs.

Informal caregiving is a time intensive task and must be met by adjustments along leisure or work margins on the part of the care provider. But do caregivers share the full burden of care with other members of their household? Standard cooperative models of the household suggest the welfare burden of care would be distributed across household members (e.g. husband and wife). However, existing literature shows that caregiving falls disproportionately on women as compared to men.

Miller and Bairoliya (2019) develop and calibrate a simple collective model of intra-household bargaining to analyze the time and resource allocation decisions associated with informal care. The authors show that a decrease in bargaining power increases one’s share of the welfare burden. If bargaining power is endogenously determined by relative earnings, the welfare cost of caregiving can fall disproportionately on a single partner, resulting in a “triple burden” of market work, home production, and caregiving. Labor market rigidities exacerbate the total welfare cost of informal caregiving to the household as well as the unequal distribution of the burden.

The paper will be available December 2019

- Published in Understanding and Measuring Care

Impact of Investing in Social Care on Employment Generation, Time- and Income-Poverty and Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation for Turkey

CONTRIBUTORS

İpek İlkkaracan, EMEL MEMIS, KIJONG KIM, TOM MASTERSON, and Ajit Zacharias

Feminist economists have long emphasized the recognition, reduction and redistribution of unpaid care work (the so-called 3R strategy) as a primary policy intervention towards closing of the gender economic gaps. Investing in a social care infrastructure is an important component of the 3R strategy. Universal access to quality care services enables reduction of the unpaid work burden through its redistribution from the domestic sphere to the public sphere. Public investment and expenditure, however, is a question of fiscal policy at the helm of macroeconomists and policy-makers who are often gender blind and also adopt the mainstream approach of public expenditure constraint. Several waves of empirical research have examined the allocation of sectoral allocation of public expenditure through macro-micro simulations.

Yet until recently, studies have failed to explore an important outcome of investing in social care from a gender perspective, namely gendered patterns of time allocation. While investing in social care creates jobs for some women, enhances their access to employment and earnings, it also increases the requirements on their time through higher paid work hours. Simultaneous access to services alleviates the unpaid work burden of women with care dependent household members. The net welfare impact for different groups of women and men taking both time- and income-effects into consideration is an empirical question.

The forthcoming paper titled “Impact of Policy Interventions at Reduction and Redistribution of Unpaid Care Work On Employment Generation, Time- And Income-Poverty And Gender Gaps: A Macro-Micro Policy Simulation For Turkey” by Ilkkaracan, Kim, Masteron, Memis, and Zacharias uses an applied macro-micro simulation policy modelling approach to explore the gendered impact of increased public expenditures on social care service expansion on new employment and income generation, time allocation to paid versus unpaid work, time- and consumption poverty. An increase in social care spending triggers two types of effects at the household and individual level: It generates new jobs improving access of previously non-employed persons (predominantly women) to employment and income generation, but at the expense of increasing paid work time of job recipients. Simultaneously, improved access to childcare services reduces unpaid work time in the households with small children. The authors use a statistically matched data set from the 2015 Time Use Survey (TUS) and the Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) in Turkey to assess the impacts on individual and household well-being, not only in terms of gains in employment and income, but also in terms of potential changes in household production responsibilities and time deficits.

The paper will be available December 2019

The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The case of South Korea

According to the Global Gender Gap Index of the World Economic Forum (2018), South Korea is one of the lowest ranked countries in the world in terms of “Economic Participation and Opportunity” (124th out of 149 countries) as of 2018. The Global Gender Gap Index also shows that South Korea ranks 88th in terms of female labor force participation and 121st in terms of gender wage equality for similar work. The average wages of women in South Korea are on average 36.7% lower than average male wages (as of 2012, own calculations based on World Klems (2014) database). These statistics reflect that there is a significant economic gender gap in South Korea despite the fact that the country is now classified as a high-income economy. Moreover, the underdeveloped care infrastructure and reliance on unpaid care labor of women is posing serious demographic and social sustainability challenges in an aging society.

Existing research on the effects of public spending show a stronger positive effect of public spending in social care and education on female employment as well as total employment compared to public investment in physical infrastructure (Antonopoulos et al., 2010; Ilkkaracan, Kim and Kaya, 2015; Ilkkaracan and Kim, 2018; De Henau et al., 2016; Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou, 2019a). These employment effects have further effects on the economy and the wellbeing of the society, as microeconomic studies across the board attest that a larger share of women’s income compared to that of men’s, is spent to satisfy the needs of the household (Blumberg, 1991; Antonopoulos et al, 2010; Pahl, 2000) and a possible increase in their income leads to increased spending on children’s education and wellbeing (Vogler and Pahl, 1994; Lundeberg et al. 1997; Cappellini, Marilli and Parsons, 2014). Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou (2019a) confirm this finding at the macroeconomic level for the case of the UK. These consequently have further demand and supply side effects on output, productivity and employment (Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou, 2019a; Seguino, 2017).

Oyvat & Onaran (2019) examines the short-run and medium-run impact of public spending in social infrastructure, defined as expenditure in education, childcare, health and social care on aggregate output and employment of men and women for the case of South Korea. They present a gendered Post-Kaleckian theoretical macroeconomic model. The authors estimate the macroeconomic effects of social expenditure using a vector autoregression (VAR) analysis for the period of 1970-2012. The results show that an increase in the public social infrastructure significantly increases the total non-agricultural output and employment in South Korea both the short and medium-run. Moreover, higher social infrastructure expenditure increases female employment more than male employment in the short-run and raises both male and female employment in the medium-run due to increasing aggregate output. Finally, estimates show that the South Korean economy is wage-led and gender equality-led in the short-run, hence overall equality-led, although the effects are economically small in comparison to the strong effects of increases social infrastructure spending, and become insignificant in the medium-run. The results indicate that sustainable equitable development and a substantial increase in employment requires a mix of both labor market and fiscal policies.

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in Gender-Aware Macromodels, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea