LTC Sector Faces a Number of Challenges, Today and Going Forward: An OECD Report

OECD Health Policy Studies has released a 2020 report “Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly.” This report addresses a number of important issues while acknowledging the tremendous impact that COVID 19 has had on elderly people and their caretakers. Across OECD countries, more than one out of every six individuals is above the age of 65, and of those roughly 60% live with multiple chronic conditions, making them even more susceptible to the potentially deadly impacts of the virus. Furthermore, many elderly individuals struggle with sufficient access to social support and lack the ability to properly deal with the mental strain of living in a world being affected by a global pandemic.

Beyond these strains, there is a crisis in workforce shortcomings of the Long Term Care (LTC) Sector, which becomes even more problematic in light of the fact that an estimated 50% of COVID 19 related deaths are occurring in LTC facilities. This OECD report begins by addressing many of these shortfalls within the LTC sector, and policies that have the potential to address them.

Within three-quarters of OECD countries, the aging population has outpaced the workforce within the sector since 2011. This is the case even in the countries that have a higher workforce supply than the OECD average such as Japan and the U.S. Within the sector, women make up 90% of the LTC workforce. Attracting a younger workforce has been particularly difficult, and on top of that maintaining workers over the age of 50 is also a challenge. This is even more concerning given that the median age of LTC workers is currently 45.

Many OECD nations have made moves toward relocating their elderly out of facilities and back into the community. This is provoked by the desire to match the preferences of their elderly populations with home-based care, in addition to containing LTC spending. However, a lack of home-based workers has made this challenging, and LTC institution-based workers remain representative of the sector’s workforce across the OECD. This is in large part due to the fact that these institutions cater to the most disabled, which requires a larger workforce. Furthermore, many community-based solutions are not yet equipped to take in these types of complex cases.

The aging of the postwar “baby boom” generation is a factor that will contribute to the increased need for LTC workforce. This also contributes to the predicted increase in labor shortages in the sector to meet the needs of this population going forward. Further, unpaid informal care workers, like that of family members that would care for this aging population, have seen an increase in their own professional workload burdens. When the workload of professional life and caretaking becomes too great, LTC facilities are a means in which to relieve some of that strain. Additionally, as birth rates decline, families become smaller and more women are pursuing professional endeavors, the availability of informal caregivers for the aging population decreases looking into the future. This contributes to another foreseen LTC workforce shortage in the future.

These shortages call for an increase in recruitment within the LTC sector. As the sector workforce ages, attracting younger workers has proven difficult as they, mostly women, are drawn to sectors that have a more appealing image such as a child or hospital care. Additionally, LTC jobs are still widely considered to be feminine positions, and the sentiment on this subject matter has been slow to change.

Foreign-born workers play a significant role in recruiting and retaining LTC workforce. They are highly over representative within LTC across the OECD when compared to other care sectors, and many of them are young, Often, they tend to come into the sector with high levels of skill sets, even overqualified. Micro-econometric analysis has shown that in the U.S. and the UK, these foreign-born workers have higher retention rates than others within the sector.

In terms of recruitment, drumming up interest in the available positions is also problematic. In some cases, many vacancies receive no applications at all. On top of this, recruiters often have a difficult time identifying qualified candidates out of those that do apply.

In order to address this, many countries have focused on four main policies:

– Target recruitment to the traditional pool

– Improve the Image of the sector

-Recruit outside the traditional pool

-Increase the recruitment of for foreign-born workers

Overall, better policies are needed in order to improve recruitment within the LTC sector, and thus far few OECD nations have implemented policies in order to do so. By addressing these issues addressed within the first section of this report, there is potential for effective improvement.

- Published in elderly care, Long Term Care Sector, Policy

Webinar (09/30/2020): Creating a Caring Economy

On Wednesday, September 30th at 10:00 -11:30 am BST, the Women’s Budget Group (WBG) will be a hosting a webinar titled “Creating a Care Economy” which will discuss the work being done within the Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy and the launch of its digital final report. This report comes at a unique time in our history, amidst a devastating global pandemic and on the brink of a harsh economic recession. The commission has taken this unprecedented time to pose the question: “do we really want to go back to business as usual?”

The Women’s Budget Group, (WBG) based out the United Kingdom, is an independent network of policy experts, academic researchers, and campaigners, harboring a vision of a “caring economy that promotes gender equality.” This non-profit organization works hard toward producing vigorous analysis intended to influence policymakers while also building the knowledge and confidence of individuals to talk about feminist economics. WBG achieves this through offering training and creating resources that are accessible and informative.

In February of 2019, WBG launched the Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy. This project works proactively to develop policies that promote gender equality across the UK, and is the first of its kind. This commission is chaired by Diane Elson.

The commission has thus far produced a number of helpful resources. To begin they have produced a short video entitled Spirals of Inequality which delves into how unpaid care is at the heart of gender inequality. This video is also accompanied by a short brief and a longer, more in-depth accompanying paper. They also have an ongoing blog, and have commissioned a number of papers focusing on four areas: Public Services, Social Security and Taxation, and an Enabling Environment. Additionally, they have gathered a number of calls for evidence, which collects evidence from many experts in varying sectors.

The final report that will be explored within this upcoming webinar will lay out a roadmap in which to build a more caring economy, outlining out the how, the why, and acting as a call to action across all the four nations encompassed within the United Kingdom.

Learn more and register for the webinar here.

- Published in Events, Gender-Equal Economy

Biden’s Care Plan Has the Potential to Change Care Work in the U.S. for the Better

Joe Biden has officially accepted the Democratic Presidential nomination, and he and his team plan to make substantial investments in the infrastructure of care in the U.S. if he wins in the Presidential election. The potential of this plan to provide much-needed support for care workers, both paid and unpaid, is more important than ever amidst the pandemic.

Even prior to this pandemic, the U.S. has long suffered a caregiving crisis. Family caregiving needs often come with incredible financial, emotional, and professional burdens. Professional caregivers, disproportionately women of color, have long been underpaid and undervalued. The pandemic has exacerbated these issues, leaving parents struggling to find the care services needed while juggling careers. There are a number of measures that have been proposed by the Biden team to address the many issues currently plaguing the overall care system in the U.S. today.

Elderly individuals in nursing homes are feeling an increasing need to be cared for at home rather than in community living situations where they are more vulnerable to COVID-19 exposure. The Biden care plan addresses this by aiming to close the existing Medicaid gap to allow for home and community-based care services while creating a state innovation fund for cost-effective direct care services. This will provide more affordable and accessible care on that front. This step will also help to alleviate the extensive waitlists now existing for those under Medicaid to enter home and community care programs, providing these services for 800,000 individuals. If implemented properly, this initiative allows the opportunity to provide more functional care systems that grant greater independence to elderly individuals, while also freeing many unpaid care workers, such as family members, to pursue professional endeavors.

This plan also proposes increasing wages and benefits for caregivers and early childhood educators while providing opportunities for training, professional growth, and unions. This particular initiative takes into consideration the fact that early childhood development is incredibly important, and quality childcare is essential for children to grow into healthy, productive members of society. Universal preschool will also be provided via tax credits and sliding scale programs. Furthermore, included is an investment into safe and developmentally appropriate childcare facilities, including bonus pay for those providers that operate non-traditional hours, such as early mornings, late evening, and weekends. By increasing access to childcare centers with more flexible hours, the burden for many families will be lifted; currently, many parents that don’t work traditional Monday through Friday hours are left scrambling to find adequate care. These initiatives overall will have significant positive impacts on working parents, particularly women. Far too often, women find themselves sacrificing professional progression and development due to the constraint of inadequate or unaffordable childcare.

For those parents who grapple with the decision to further their education as a result of unaffordable and reliable care, investment in childcare centers at community colleges is also included in this plan.

Lastly, expanding the awareness of the Department of Defense fee assistance childcare programs so that all military spouses have the ability to pursue their professional development and education.

In order to pay for these initiatives, the Biden team has estimated a cost of $775 billion over the span of ten years, to be funded by rolling back certain tax breaks for those earning over $400,000 annually. A $5000 tax credit or Social Security credits for those providing unpaid care for members of their family is also proposed. Further, the plan seeks to offer low- and middle-class families up to $8000 in tax credits to assist in paying for childcare. For those that choose not to claim this credit, high-quality care is to be provided on a sliding scale, where it is estimated that families will not pay over $45 per week.

Although this plan is incredibly ambitious, and its implementation is not a guarantee, it sets a precedent that has been long lacking within the U.S. care work sphere. Implementation of these initiatives on any scale would prove beneficial to both the paid and unpaid care economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy, U.S.

Reflections on Parental Caregiving and Household Power Dynamics

A growing concern in many countries is an aging population and an increase in the number of elderly in need of long-term care. However, the impact of elderly care on the well-being of care providers remains relatively understudied. One of the primary factors which complicate analysis is that a majority of elderly care is provided informally by family members, with adult children often comprising the largest share of care providers. The pervasiveness of unpaid care due to cultural or family ties has even limited the development of long-term care insurance in economically advanced regions like Europe. However, while children may provide an informal safety net, parental caregiving is a time-intensive task and must be met by adjustments in leisure or work hours on the part of the care provider. Hence, in order to understand the full macroeconomic implications of growing elderly care needs and the appropriate policy response, it is imperative to understand how households cope with these caregiving needs.

Economic models of elderly care have focused almost exclusively on inter-generational bargaining between parents and children or bargaining among siblings. However, little attention has been paid to the influence of care demands on the power dynamics between partners within a household (e.g. husband and wife). This is despite data showing that caregiving falls disproportionately on women and that some caregivers respond to increased parental care needs by reducing work hours, taking more flexible jobs, or by quitting paid work entirely. Moreover, caregiving may have spillover effects on the caregiver’s spouse or partner. For example, a spouse may work longer hours or reduce their spending to cope with fewer hours of paid work by the caregiver. So it is unclear to what extent partners reallocate their time and resources and share the burden of parental care needs when they arise.

In the study detailed in the CWE-GAM working series paper published May 2020, we develop a theoretical model to explore how unpaid parental caregiving can affect the allocation of time and resources across partners under different household power structures. As parental caregiving disproportionately falls on daughters, we consider a model in which a woman’s parent is in need of time-intensive care. The provision of care across partners is then a bargained outcome between the couple. We not only examine how power dynamics and work arrangements impact caregivers and their partners but also how these factors may influence unmet care needs and care recipients.

After developing our model, we use cross-country data from the Survey of Health, Age-ing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) to illustrate our theoretical concepts with some numerical exercises. Broadly our results indicate caregivers may face a “triple burden” of market work, domestic chores, and caregiving. For example, our model predicts that for a duel-earning couple in France, the total cost of unpaid parental caregiving to the male is only about 57% that of their female partner—a skewed but shared burden. The higher cost to the female stems from two sources; (1) relatively fewer hours of leisure due to her provision of unpaid care; (2) the additional mental or emotional cost of leaving her parent with some level of unmet care needs.

Overall, our theoretical and numerical results show that ignoring bargaining power differentials across partners can misrepresent the true cost of unpaid parental caregiving by not taking into account the uneven distributional consequences. Moreover, our cross-country findings suggest that lower female bargaining power results in a larger burden on female caregivers and additional unmet care needs for their parents. If bargaining power is determined by relative earnings, government policies subsidizing long-term care could decrease the well-being gap within a household by providing financial relief and improving the bargaining position of the caregiver. This could further result in reduced levels of unmet care needs and improved outcomes for elderly care recipients. We further show that inflexible work arrangements also exacerbate the total cost of unpaid caregiving to the household as well as the unequal distribution of the burden. This implies policies that promote flexibility, such as caregiver leave or part-time options, could provide substantial relief, particularly to high-intensity caregivers.

This blog was authored by Ray Miller and Neha Bairoliya, who are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in elderly care, Rethinking Macroeconomics

Reflections on The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment in South Korea

In terms of “Economic Participation and Opportunity” South Korea is one of the lowest-ranked countries in the world (124th out of 149 countries) as of 2018. Global Gender Gap Index also shows that South Korea ranks 88th in terms of female labour force participation and 121st in terms of gender wage equality for similar work. The average wages of women in South Korea are on average 36.7% lower than average male wages (as of 2012, Oyvat and Onaran, 2020). Hence, there is a significant economic gender gap in South Korea despite the fact that the country is now classified as a high-income economy. Moreover, the underdeveloped care infrastructure and reliance on unpaid care labour of women is posing serious demographic and social sustainability challenges in an aging society.

Our new research analyses the effects of public social expenditure in education, health and social care and closing gender pay gap on aggregate output and female and male employment (Oyvat and Onaran, 2020). We introduce a structuralist gendered model of the demand and supply sides of the economy with endogenous productivity, labour supply and wage bargaining. Empirically, we use a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) analysis to econometrically estimate the effects of an increase in social infrastructure spending, female and male wages, and closing the gender pay gap on aggregate output and employment of men and women in South Korea for the period of 1970-2012.

Public social expenditure, specifically education played an important role in the rise of South Korean economy. The social sector has not only been a sector that is crucial for economic growth in South Korea, but it has also been important for generating female employment and closing gender employment gaps. The share of women in employment in the social sector (education, healthcare and social care) has been greater than in the rest of the economy since the 1970s. The share of female employment in the social sector in South Korea increased from 47.4% during the period of 1988-1997 to 58.3% in 1998-2007 and to 63.2% in 2008-2012. In contrast, the share of female employment in the rest of the non-agricultural economy is only 27.7% in 1998-2007 and 28.4% in 2008-2012. The female employment share even in sectors which traditionally had a high female employment such as food, beverages, tobacco, textiles, leather, and footwear or electrical and optical equipment have been steadily declining and is lower than the female employment share in the social sector in the post-1998 period.

Our theoretical framework identifies the possible channels through which public social spending influences total output, male and female employment. In the short-run, the increase in public social spending has a positive effect on total output and female and male employment. While higher social public expenditure may increase public debt/GDP in the short-run, this negative effect is moderated as tax revenues also increase alongside aggregate income, which in turn offsets any potential crowding out effect on private investment. As the female employment share is significantly larger in the social sector than in the rest of the economy, higher public social expenditure is expected to reduce the gender employment gap.

In the medium-run, higher public social expenditure is expected to have not only a direct positive effect on labour productivity, but also an indirect positive effect through i) higher output and benefits of increasing returns to scale; ii) higher wages creating incentives for adopting labour-saving technologies; and iii) higher private expenditure in education, health and social care by the households as income, in particular female income increases. Due to these effects on productivity, we refer to public social expenditure as social infrastructure investment.

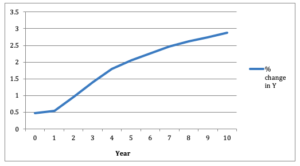

Figure 1: The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in social expenditure (YH) on aggregate non-agricultural output (Y)

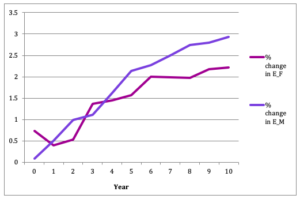

The estimation results show that a 1% increase in the public social expenditure in South Korea increases non-agricultural output by 0.5% contemporaneously, and by 2.3% in cumulative over six years and 2.9% over ten years (Figure 1). As a result female and male employment increase contemporaneously by 0.7% and 0.1% respectively (Figure 2). The short-run impact is larger for female employment as the share of women is significantly higher in the social sector compared to the rest of the non-agricultural sector. In ten years female and male employment increase by 2.2% and 2.9% respectively. Finally, labour productivity increases by 0.22% over four years.

Figure 2: The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in social expenditure (YH)on female (EF) and male employment (EM)

The results also show that an increase in female wage rate has a significant positive effect on output. A 1% increase in female wages leads to a cumulative increase in output by 0.2% in year 3 and by 0.3% over 10 years. This shows that the South Korean economy is female wage-led/gender equality-led in the medium-run; hence higher equality is conducive to growth and development. The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in the male wage rate on output is 0.2% over 10 years. It is also important to emphasize that higher male wages are not an impediment to growth in South Korea. The results also indicate the importance of improving gender equality as part of an equality-led development policy.

Our research shows that an equitable development path in which both average wages increase and gender gaps close via an upward convergence in the wages of men and women is possible in South Korea. However, the effects from wages are economically small in comparison to the strong effects of social spending. The results indicate that sustainable equitable development and a substantial increase in employment requires a mix of both labour market and fiscal policies.

This blog is authored by Cem Oyvat and Özlem Onaran are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea