Investing in Quality Care has Positive Macroeconomic Effects

Recent research by Lenore Palladino and Chirag Lala of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts Amherst, examines the effects of critical public investment in childcare, home health care, and paid family and medical leave (PFML) for the U.S. workforce, as proposed by the American Jobs Plan and the American Family Plan by the Biden-Harris Administration.

The authors find that investing in childcare and home health care workforce has positive macroeconomic effects, and the care workforce spends its own money on goods and services through the rest of the economy. They also find that PFML positively boosts the economy, as workers spend the wage replacement income they earn.

The authors model the effects of a $42.5 billion annual investment in childcare and a $40 billion investment in home health care with a minimum wage of $15 an hour and find that the proposed investment can create 564,000 additional jobs throughout the economy, and results in an increase in labor income of $82 billion annually. They find that universal paid family and medical leave, as proposed by the American Families Plan, would increase household income nationally by $28.5 billion, of which $19 billion would be wage replacement directly from the paid leave program, and $9.4 billion would be income earned by workers throughout the economy as people receiving wage replacement spend money on goods and services. This means that for every dollar spent on wage replacement as part of the paid leave program, other workers would earn an additional $.50.

RESEARCH BRIEF: The Economic Effects of Investing in Quality Care Jobs and Paid Family and Medical Leave

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, program manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project.

- Published in Care Infrastructure, Child Care, Elder Care, elderly care, Gender-Equal Economy, Healthcare, Macroeconomics, Policy

A Gender Lens on COVID-19: Investing in Nurses and Other Frontline Health Workers to Improve Health Systems

In a recent CGD blog post, author Megan O’Donnell highlighted seven areas where long-run, gender-responsive thinking can help to insulate against the consequences of pandemics like COVID-19 and their disproportionate impacts on women and girls. Here we take a deeper dive into one of those areas: the promotion of a gender-equal global health workforce in which the occupations where women predominate, such as nursing and community health work, are valued, prioritized, and properly resourced.

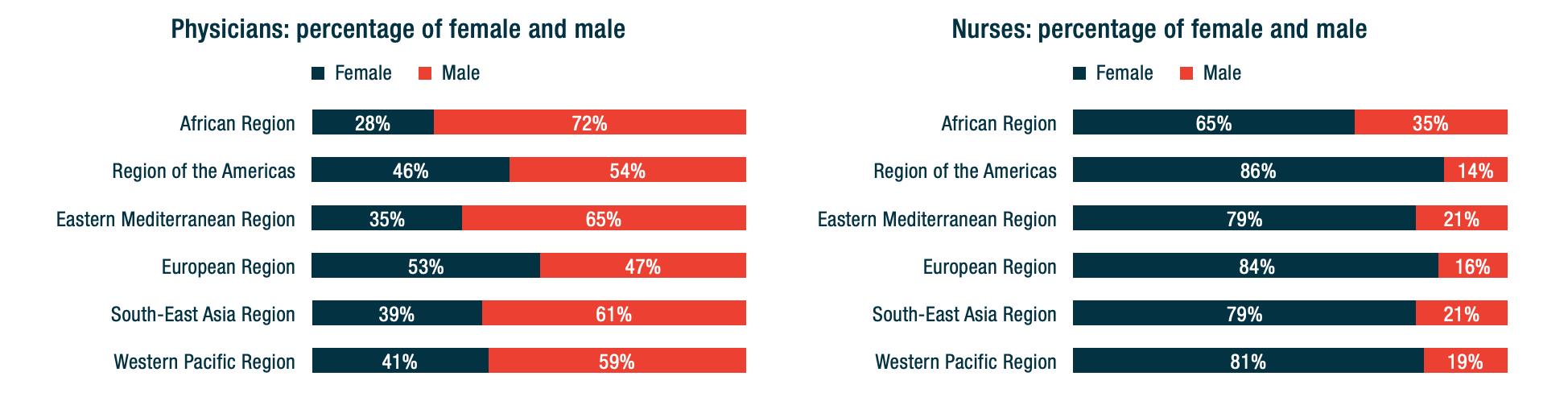

Worldwide, women make up anywhere from 65 percent (Africa) to 86 percent (Americas) of the nursing workforce. Their jobs are critical to the health, safety, and security of communities on any given day, and particularly in times of a global pandemic. And yet, more obviously now than ever before, we face a global nursing shortage. To address this critical short fall and ensure sufficient numbers and distribution of health workers to provide both emergency and routine care in time of crisis, governments need to increase and improve their long-term investment in nurses, including by addressing gender gaps in the health workforce.

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities, Healthcare

How Will COVID-19 Affect Women and Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries?

Policymakers should be thinking—and worried—about how COVID-19 is expected to disproportionately affect women and girls. Gender inequality can come into even starker focus in the context of health emergencies. With COVID-19 continuing to spread, what do we see so far—and what can we expect in the future—in terms of the impacts on women and girls?

Wenham, Smith, and Morgan discuss gendered impacts in their article, “COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak,” in the Lancet. Women appear to be less likely to die from COVID-19: “Emerging evidence suggests that more men than women are dying, potentially due to sex-based immunological or gendered differences, such as patterns and prevalence of smoking.” But keep in mind that “current sex-disaggregated data are incomplete, cautioning against early assumptions.” In other research, data from 1,000+ patients in China show that “41.9% of the patients were female.” (Guan and others 2020). But beyond these direct effects, most of the other impacts affect women negatively and disproportionately.

Wenham, Smith, and Morgan highlight that women will be more affected in places with more female health workers. In an analysis of 104 countries, Boniol and others (2019) show that women form 67 percent of the health workforce (see the figure below). In China, “an estimated 3000 health care workers have been infected and at least 22 have died” (Adams and Walls 2020). As the pandemic spreads, the toll on women health workers will likely be significant.

Figure. Gender distribution of health workers across 104 countries

Source: Boniol and others (2019)

Here are other areas highlighted by Wenham, Smith, and Morgan:

– School closures are likely to have a differential impact on women, who in many societies take principal responsibility for children. Women’s participation in work outside the home is likely to fall. (My colleagues Minardi, Hares, and Crawfurd have written about other impacts of school closures during an epidemic.)

-Travel restrictions will affect female foreign domestic workers. Of course, they also affect male migrants. The distribution will vary by country. Research by Korkoya and Wreh (2015) found that 70 percent of small-scale traders in Liberia are women, so domestic travel restrictions during the Ebola outbreak disproportionately affected women.

-Health resources normally dedicated to reproductive health go towards emergency response. During the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, for example, the “decrease in utilization of life-saving health services translates to 3600 additional maternal, neonatal and stillbirth deaths in the year 2014-15 under the most conservative scenario” (Sochas, Channon, and Nam 2017). In my own research (with Goldstein and Popova), we found that the disproportionate loss of health workers in areas that had few to begin with would likely lead to higher maternal mortality for years to come.

-When women have less decision-making power than men, either in households or in government, then women’s needs during an epidemic are less likely to be met.

Here are four additional concerns:

-Sexual health: During the school closures of Sierra Leone’s Ebola outbreak, “a reported increase in adolescent pregnancies during the outbreak has been attributed largely to the closure of schools.” (UNDP 2015). Bandiera and others find that in villages highly disrupted by Ebola, girls were “10.7 percentage points more likely to be become pregnant, with most of these pregnancies occurring out of wedlock.” A United Nations report gives an even higher estimate of 65 percent. The absorption of health resources by emergency response may also lead to disruptions in access to reproductive health services.

Many girls didn’t return to schools once they reopened, and there were increases in unwanted sex and transactional sex. (Notably, Bandiera and others also find that girls in villages where there were established “girls’ clubs”—safe spaces for teenage and young adult girls to gather and get job and life skills—before the epidemic experienced fewer of these adverse effects.)

-Intimate partner violence rises in the wake of emergencies: Parkinson and Clare document a 53 percent rise in the wake of an earthquake in New Zealand and nearly a doubling in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in the United States. Mobarak and Ramos find that in Bangladesh, increased seasonal migration reduces intimate partner violence, at least in part because women spend less time with the potential perpetrators of that violence. Travel restrictions may be expected to have the opposite effect.

-The burden of care usually falls on women—not just for children in the face of school closures, but also for extended family members. As family members fall ill, women are more likely to provide care for them (as documented during an Ebola outbreak in Liberia, with AIDS patients in Uganda, and in many other places), putting themselves at higher risk of exposure as well as sacrificing their time. Women are also more likely to be burdened with household tasks, which increase with more people staying at home during a quarantine.

-As Mead Over and I have discussed, health crises can trigger economic crises. Economic crises affect women disproportionately, particularly in low-income countries. Sabarwal and others found that men’s labor force participation remained largely unchanged during economic crises, whereas women’s labor force participation rose in the poorest households and fell in richer households.

-Last week, the World Health Organization declared that “this is the first pandemic caused by a coronavirus.” There have been more than 168,000 confirmed cases and more than 6,600 deaths in 148 countries as of publication of this blog. The impact of this pandemic will be felt for years to come. As women are often disproportionately affected by the follow-on effects of the disease, we have to make sure that we keep women’s rights and needs front and center in our responses. A first step in doing that is making sure that women are a central part of the teams designing those responses.

Contributed by David Evans, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, working on education, health, and social safety nets.

This post benefitted from comments provided by Susannah Hares, Megan O’Donnell, Emily Christensen Rand, and Rachel Silverman.

Original blog published on Center for Global Development website March 16, 2020, see here for the original posting

Reposted with permission from David Evans, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development

- Published in COVID 19, Healthcare

Playing the Long Game: How a Gender Lens Can Mitigate Harm Caused by Pandemics

When crisis hits, longer-term thinking can easily, and understandably, be cast as a distraction or a luxury—even when it relates to tackling critical issues like gender inequality, climate change, or extreme poverty.

Speaking personally, I’ve felt a bit silly trying to push forward projects that focus on gender lens investing or women’s economic empowerment in the last few weeks, given that my colleagues’ and collaborators’ attention, and frankly much of my own, lies elsewhere, and with something that seems much more pressing.

But for those of us who are in the position of privilege to continue thinking long term, it’s our responsibility to do so. Working towards structural changes that will take longer to come to fruition, especially those that relate to reducing global inequality, is the only way to radically decrease the extent of harm caused by moments of crisis, especially for vulnerable populations.

Dismantling unequal power structures, and in turn ensuring that every individual—regardless of gender, age, income level, national origin, and so on—has a safety net protecting them from vulnerability to health scares, income loss, and threats of increased violence, will allow us to focus on crisis without fearing fallout across every dimension of life.

In times of pandemic, the economically vulnerable cannot afford to stay home. Women in quarantine are facing increased risks of intimate partner violence. Girls staying home from school in some parts of the world may not have the opportunity to return. And none of this would be the case if we more effectively tackled the forms of inequality that underlie these realities. Then a virus could be a virus — assuredly deadly and destructive from a health perspective – but without inciting increased abuse, poverty, and lost prospects.

My colleague David Evans, drawing upon work by Claire Wenham, Julia Smith, and Rosemary Morgan in The Lancet, recently highlighted a range of problems stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic that disproportionately impact women and girls. In hopes of continuing to move the conversation forward, I propose some solutions to those problems here, and welcome others to add to this initial list. To be clear, these actions should not distract from immediate measures to address the pandemic. But we also can’t afford to risk forgetting about them when the focus on COVID-19 has faded; otherwise history is doomed to repeat itself.

1. Promote a Gender-Equal Health Workforce

Because the health workforce is disproportionately women (67%), women are at a higher risk of exposure to the virus within medical facilities.

More doctors worldwide are still men. But the vast majority of the global health workforce consists of nurses, community health workers, and others who are less highly compensated. All health workforce jobs need to become increasingly well-compensated, high-quality jobs. Not only will this incentivize men to seek these positions, destigmatizing their current positioning as “feminine” and dismantling occupational sex segregation within the healthcare sector, but it will also ensure that those on the frontlines of protecting populations from pandemics don’t also have to fear economic fallout on a day-to-day basis.

The number of women doctors is rising. Research from other sectors tells us what works to combat occupational sex segregation, including men acting as mentors supporting women to “cross over” into higher-paying occupations. These efforts will have to be paired with those that increase the perceived (and actual) value of work in sectors, including nursing and other frontline health work, where women dominate. More research is needed on this front, both on what works to incentivize men to take up traditionally “feminine” roles and how to avoid unintended displacement of women from those occupations.

2. Protect (and Expand) Existing Health Resources

With all hands on deck to fight COVID-19, particular groups of women and girls face other health risks.

Health facilities should not have to choose between providing lifesaving care in the face of pandemics and continuing to provide support for those in need in other areas, including pregnant women, adolescent girls (who have the highest prevalence of HIV infection, and in need of life-saving medication to keep their immune systems strong), and all women and girls in need of contraceptive access.

Increased investments in health are needed to ensure critical day-to-day care is not compromised during times of crisis. Establishing a Global Health Security Challenge Fund would help ensure countries are prepared to balance day-to-day needs with additional burdens in the face of pandemic, and evidence-based prioritization strategies are needed for when resources cannot be expanded.

3. Reduce and Redistribute Unpaid Care Work Burdens

As schools close and people fall ill, women and girls will assume increased unpaid care work burdens.

Under business-as-usual scenarios, women and girls do more than their fair share of unpaid care work, which limits their educational attainment, workforce participation and advancement, and leisure time. To lessen these burdens in times of crisis and more generally, we need increased investments in child and elder care, and in the poorest countries, gender-responsive energy, water, and sanitation infrastructure that would reduce the time women and girls must spend collecting water and fuel, as well as cooking and cleaning. We also need shifts in household norms that mean men assume more unpaid care responsibilities. Initiatives focused on promoting women’s economic empowerment, such as 2X Challenge and the Women’s Global Development and Prosperity (W-GDP) initiative, as well broader investments in gender equality and economic growth, must prioritize reducing and redistributing women and girls’ unpaid care work.

4. Address Gender-Based Violence

With quarantine measures imposed and stress heightened, women are at increased risk of violence committed by their partners and family members, and essential support services are absent.

Early reports suggest that gender-based violence rates are increasing in light of COVID-19 quarantining, consistent with evidence documenting increased violence in other crisis settings. Gender-based violence needs to be elevated as its own public health crisis, and resourced accordingly.

We’re far from meeting this objective, considering that all OECD donors combined allocated less than $200 million to addressing violence against women according to 2016-17 data, and over half of this financing came from just three countries (Australia, Canada, and Norway). Increased resources should target evidence-based approaches, such as Promundo’s MenCare program.

In pandemic contexts, preparations for social distancing should include considerations of how individuals will be able to access social services when faced with violence in their households. The World Bank has taken a step in the right direction in positioning interpersonal and gender-based violence as priorities to address in its new Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Strategy, though time will tell how the bank and other donor institutions finance this priority.

5. Guarantee Girls’ Education

With schools closing as part of social distancing measures, girls who already face pressure to drop out of school may not return.

Even absent crisis, tens of millions of girls globally face pressures to drop out of school to care for siblings and do other unpaid domestic work, contribute to supporting their households financially, and/or marry and have children when they are still children themselves. These pressures may be heightened due to interruptions in their education, as observed when Ebola hit West Africa. School closures, especially those impacting adolescent girls, should be weighed against longer-term risks related to girls’ school drop-out and limited school-to-work transition prospects as a result. Where possible, efforts should be made to incentivize parents to allow their children to return to school and to ensure consistent access to sexual and reproductive health services in the interim, as unintended pregnancy is cited as a reason for girls’ failure to return to school.

6. Promote Women’s Economic Opportunities

Across the globe, women are more likely to work jobs that are low-paid, informal, and lacking in benefits.

In large part due to the disproportionate unpaid care work women take on, they are less likely to be employed full-time, in the formal workforce, or in jobs that provide paid sick leave, unemployment insurance, and other protections.

We must continue to invest in evidence-based programs and policies that improve women’s economic opportunities and support organizations such as the Self-Employed Women’s Association and Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing—organizations that are well-positioned to provide and advocate for dignified work.

Cash transfers should be considered as a means of ensuring a social safety net for those most in need. Critical to transfers’ success will be (1) ensuring that delivery mechanisms (through digital technology or otherwise) are properly designed and implemented and (2) that those in need, including low-income populations and workers vulnerable to economic backslides because of the virus, are prioritized.

7. Ensure Women’s Representation in Decision-Making and Critical Research

Women are not equally represented in decision-making roles responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force is over 90 percent men, and the team Prime Minister Johnson just assembled to lead the United Kingdom’s COVID-19 response is all men. As in the contexts of peace and security, international trade, and climate change, an exclusionary approach to decision-making will yield inferior decisions: those that don’t account for the needs and constraints of populations absent from the table.

Going forward, decision-making teams should be equally representative of men and women, and also prioritize other forms of inclusion, such as those based on race and ethnicity, as called for by Women in Global Health’s Operation 50/50 campaign.

Women must also be equally represented in clinical trials as biomedical treatments and other interventions are developed. As my colleague Carleigh Krubiner has noted speaking to the context of Ebola, women who are pregnant or breastfeeding are typically excluded from experimental studies, and in some high-fertility contexts, this means up to 80 percent of reproductive age women are virtually invisible in trial samples. Lack of representation means a lack of essential data on the types of prevention methods, treatments, and other interventions that work for women, risking higher fatality rates and other complications.

Times of crisis magnify the cracks in our systems and highlight disproportionate risks to the most vulnerable among us. COVID-19’s impacts, those already felt as well as those still anticipated, should serve as a wake-up call. They should spur action to address underlying inequalities, including those that disadvantage women and girls worldwide and make the consequences of a pandemic even worse than they would otherwise be. Increased prioritization of women and girls’ health, education, economic opportunity, safety, and decision-making power can help create a world where no one falls through the cracks. Decision-makers should realize this is inextricably linked to today’s pandemic response.

Contributed by Megan O’Donnell Assistant Director, Gender Program and Senior Policy Analyst at Center for Global Development

Original blog published on Center for Global Development website March 18, 2020, see here for the original post

Reposted with permission from Megan O’Donnell Assistant Director, Gender Program and Senior Policy Analyst at Center for Global Development

- Published in COVID 19, Gender-Equal Economy, Healthcare