Biden’s American Jobs Plan Could Be Monumental for the Care Economy in the U.S.

Last month, the Biden administration revealed the details of the $2 trillion American Jobs Plan.

The plan recognizes that investing in the care economy, as with investments in traditional infrastructure, can lift incomes, unleash productivity, and pave the path towards a more equitable economic recovery and growth.

Addressing the care crisis

Built into the plan is a pledge to “solidify the infrastructure of our care economy by creating jobs and raising wages and benefits for essential home care workers.” The plan calls for Congress to invest $400 billion towards expanding access to quality, affordable home- or community-based care for aging relatives and people with disabilities. These investments will help Americans to obtain the long-term services and support they need, while creating new jobs and offering care workers a long-overdue raise, stronger benefits, and an opportunity to organize or join a union and collectively bargain. Research has shown that increasing the pay of care workers leads to better quality care overall. Through creating well-paying care jobs with benefits and o collectively bargaining rights, as well as building state infrastructure, the plan aims to improve both the quality of job for care workers and the quality of service for care recipients.

Lack of access to childcare makes it harder for parents, especially mothers, to fully participate in the workforce, hurting families and hindering U.S. growth and competitiveness. In areas with the greatest shortage of child care slots, women’s labor force participation is about three percentage points less than in areas with a high capacity of child care slots. The pandemic has severely exacerbated this problem with more than 1 in 4 facilities still remaining closed as of December 2020. President Biden is calling on Congress to provide $25 billion to help upgrade child care facilities and increase the supply of child care in areas that need it most. These funds are to be provided through a Child Care Growth and Innovation Fund for states to build a supply of infant and toddler care in high-need areas. Also included in this $25 billion is a call for expanded tax credits to incentivize businesses to provide care facilities at their establishments. This will grant accessible, high quality care and learning environments for children of employees. This particular part of the plan is structured so that employers will receive 50 percent of the first $1 million of construction costs per facility.

Investment in care is investment in infrastructure

As Cecelia Rouse, Chair of the Economic Advisors for the Biden administration, recently indicated during a recent press conference, we need to “upgrade our definition of infrastructure” to include the care economy. Rouse defended the Biden administration’s plan to spend $400 billion of the infrastructure plan’s budget on the care economy, defining it as a legitimate infrastructure investment and a key component to addressing economic inequities in the U.S. The care economy is critical to U.S. economic activity, and its absence would greatly hinder economic productivity. The inclusion of care work and the care economy in the American Jobs Plan is a critical first step in mending a critically broken care infrastructure in the U.S.

Still, it is only the first step. The U.S. is the only industrialized nation that fails to provide national paid family leave and medical leave programs, and where hundreds of thousand sit on waiting lists for desperately needed home care. LeadingAge, which represents service providers in the sector, estimates that half of all Americans will need long-term services and support after turning 65, and that by 2040, a quarter of the U.S. population will be 65 or older. In addition to the President’s proposal for the care economy, we also need investments to finally put America on a path to universal childcare and early learning, national paid family and medical leave and paid sick days for all workers. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed both the importance of care work and the vulnerabilities of our care infrastructure. At the same time, it has also created an opportunity for us to rethink the value of care and care work, opening ways for us to rebuild a more resilient care infrastructure and a more inclusive economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Economic Recovery, Policy, U.S.

Women and the Pandemic in the U.S.

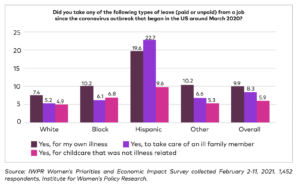

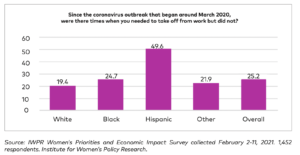

Institute for Women’s Policy Research released a report in February 2021”IWPR Women’s Priorities and Economic Impact Survey” outlining a recent poll of 1452 women in the U.S. The findings are backdropped by the experience of women throughout the pandemic and resulting economic turndown, in which 2.35 million women have left the workforce since February 2020.

Some of the key findings from this survey are:

- 1 in 4 women report that they are worse off financially than one year ago

- Nearly half of all women are worried about the financial situation of their families

- 1 in 4 women report having needed to take time work off but did not do so

- 40% of women reported care demands stopped them from working or forced them to reduce hours

- 69% of women support paid sick time to have a child, recover from a serious health condition, or care for a family member

- 20% of women with children want the Biden administration to address childcare and education in the first 100 days

In terms of women experiencing reduced paid work as a result care demands, this has also been pointed to within recent working papers put out by the

The impact of care demands on women’s paid work is explored in a number of Care Work and the Economy Working Paper Series. For instance in two recent papers, “Gender Wage Equality and Investments in Care: Modeling Equity and Production” and “Parental Caregiving and Household Dynamics”.

Education and childcare were listed among the top priorities for the Biden administration to address within the first 100 days among survey participants. This is largely because women’s ability to reenter the workforce largely depends upon safe reopening of schools and childcare facilities.

Latinas have been hit particularly hard according to this survey, reporting the highest levels of taking leave from jobs in order to provide care. However, across all ethnicities, 69 percent of women expressed strong support for paid sick leave and the ability to take time away from work to provide care or recover from illness.

The Unites States remains the only high-income country in in the world that fails to provide guaranteed paid sick or family leave for workers. The Family Medical Leave Act, which provides unpaid job protection, and only for about 56 percent of workers. The Families First Coronavirus Relief Act has provided access to paid leave as a result of the pandemic but falls short in the fact that more than 100 million workers are excluded from this because they are caregivers.

In order to address the many issues identified throughout this survey, there is strong need for targeted programs and policy solutions that will aid a gender equitable recovery. This recovery should not only address immediate short term needs but include long term strategies that will create more resilient systems that recognize the contributions of women to the workforce, society and family structure.

IWRP specific recommendations for the short term are:

- Continuing economic impact payments

- Expanding access to affordable healthcare

- Providing paid sick and medical leave

- Raising the federal minimum wage

- Building a new childcare infrastructure

Equitable economic recovery necessitates a national care system that meets the needs of all families, raises wages and provides quality childcare, treating it as a public good instead of a private obligation.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Policy, Policy Briefs & Reports, U.S.

A New National Model for Preschool and Childcare in the U.S.

Frustrated with decades of inaction at the national and state level, residents of Multnomah County, Oregon put a measure on the ballot this past November to create a free, year-round, universal preschool program for all three and four year-olds in the county. Approval was resounding, the vote nearly two to one in support.

Despite years of compelling evidence for universal preschool as a powerful economic development strategy that improves educational outcomes while fighting poverty and inequality, as well as gender and racial disparities, the U.S. lags far behind many nations in the provision of early childhood education and care. But – unlike other desperate needs such as affordable housing and health care – early childhood education is relatively inexpensive, making it possible for a city or county to mount its own program.

The preschool model being created for the city of Portland, and the rest of Multnomah County, should set a new standard for public preschool programs in the U.S., meeting the needs of children, their families and preschool staff. To help children thrive and obtain the most from their later education, Multnomah County will work with a range of providers to offer a high quality program, in different languages and cultures, and in a variety of settings, including schools, centers, and family child care. The program will attain full universality within ten years, prioritizing the enrollment of children from communities of color and families with lower incomes in the early years as the program builds.

To ensure that the program works for families, they’ll also have a choice of schedules, including full and part-time, school year or year-round, and weekends as well as week days, for up to five days a week. All children may attend without cost for up to six hours a day, with ten hours a day free for families in the lower half of the income distribution.

To retain the skilled, experienced, dedicated – and almost entirely female – staff so critical to quality, teachers’ salaries will double the going rate, to equal those of kindergarten teachers. The wage floor for all classroom workers, including aides and assistant teachers, will be significantly above the minimum wage, starting at just under $20 an hour in the autumn of 2022 when the first children will be enrolled.

No public preschool system in the U.S. has yet paid a living wage to all staff members, despite cripplingly low levels of staff retention. Economist Catherine Weinberger has shown that, in the U.S., four of five employed women with college degrees in early childhood development and education do not work with young children. By contrast, high proportions of college graduates educated as nurses, accountants and others work in jobs that draw directly on their academic training.

Further, Multnomah County’s new universal preschool program will be funded by a county income tax levied on approximately eight percent of the county’s highest income households, addressing skyrocketing economic inequality and the forty-year concentration of income at the very top.

The Multnomah County ballot measure campaign was supported by an undeniable coalition of teachers, unions, organizations representing communities of color, civic and feminist groups, small business owners and environmental advocates– not to mention galvanized parents, child care workers, preschool providers, public health care workers, doctors, economists, school board members and elected officials. Two separate campaigns worked independently for years to prepare a ballot measure, emerging to find themselves aimed at the same election. The more ambitious was led by the Portland chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America while the other was headed by a philanthropy, called Social Venture Partners, working with an elected County Commissioner. The two campaigns were able to merge on their strongest combined program, after the bolder plan gathered thirty-two thousand signatures, more than enough to qualify for the ballot.

Key to our success, I believe, was creating a program that works for children, parents and workers. Too often in the U.S., fear of raising taxes has led to small, part-time and ill-paid programs serving only the least advantaged, and supported by a limited base of advocates for children from lower-income households. High quality, universal programs are not only more successful at improving educational outcomes for disadvantaged children, but enjoy the popularity necessary to sustaining funding into the future while allowing parents to work more hours or gain additional schooling.

This blog was contributed by Mary C. King who is Professor of Economics Emerita at Portland State University, Vice-President of the Oregon Center for Public Policy, Co-Chair of the Oregon Scholars Strategy Network and a founding board member of Family Forward Oregon. She has spent the past three years campaigning for universal preschool in Multnomah County, where voters decisively approved the creation of a free, year-round, full-day universal preschool program on November 3, 2021.

- Published in Child Care, U.S., Universal Preschool

Biden’s Care Plan Has the Potential to Change Care Work in the U.S. for the Better

Joe Biden has officially accepted the Democratic Presidential nomination, and he and his team plan to make substantial investments in the infrastructure of care in the U.S. if he wins in the Presidential election. The potential of this plan to provide much-needed support for care workers, both paid and unpaid, is more important than ever amidst the pandemic.

Even prior to this pandemic, the U.S. has long suffered a caregiving crisis. Family caregiving needs often come with incredible financial, emotional, and professional burdens. Professional caregivers, disproportionately women of color, have long been underpaid and undervalued. The pandemic has exacerbated these issues, leaving parents struggling to find the care services needed while juggling careers. There are a number of measures that have been proposed by the Biden team to address the many issues currently plaguing the overall care system in the U.S. today.

Elderly individuals in nursing homes are feeling an increasing need to be cared for at home rather than in community living situations where they are more vulnerable to COVID-19 exposure. The Biden care plan addresses this by aiming to close the existing Medicaid gap to allow for home and community-based care services while creating a state innovation fund for cost-effective direct care services. This will provide more affordable and accessible care on that front. This step will also help to alleviate the extensive waitlists now existing for those under Medicaid to enter home and community care programs, providing these services for 800,000 individuals. If implemented properly, this initiative allows the opportunity to provide more functional care systems that grant greater independence to elderly individuals, while also freeing many unpaid care workers, such as family members, to pursue professional endeavors.

This plan also proposes increasing wages and benefits for caregivers and early childhood educators while providing opportunities for training, professional growth, and unions. This particular initiative takes into consideration the fact that early childhood development is incredibly important, and quality childcare is essential for children to grow into healthy, productive members of society. Universal preschool will also be provided via tax credits and sliding scale programs. Furthermore, included is an investment into safe and developmentally appropriate childcare facilities, including bonus pay for those providers that operate non-traditional hours, such as early mornings, late evening, and weekends. By increasing access to childcare centers with more flexible hours, the burden for many families will be lifted; currently, many parents that don’t work traditional Monday through Friday hours are left scrambling to find adequate care. These initiatives overall will have significant positive impacts on working parents, particularly women. Far too often, women find themselves sacrificing professional progression and development due to the constraint of inadequate or unaffordable childcare.

For those parents who grapple with the decision to further their education as a result of unaffordable and reliable care, investment in childcare centers at community colleges is also included in this plan.

Lastly, expanding the awareness of the Department of Defense fee assistance childcare programs so that all military spouses have the ability to pursue their professional development and education.

In order to pay for these initiatives, the Biden team has estimated a cost of $775 billion over the span of ten years, to be funded by rolling back certain tax breaks for those earning over $400,000 annually. A $5000 tax credit or Social Security credits for those providing unpaid care for members of their family is also proposed. Further, the plan seeks to offer low- and middle-class families up to $8000 in tax credits to assist in paying for childcare. For those that choose not to claim this credit, high-quality care is to be provided on a sliding scale, where it is estimated that families will not pay over $45 per week.

Although this plan is incredibly ambitious, and its implementation is not a guarantee, it sets a precedent that has been long lacking within the U.S. care work sphere. Implementation of these initiatives on any scale would prove beneficial to both the paid and unpaid care economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy, U.S.

Digital Forum on Reopening Long Island and Building a Fair Economy:Care Work in the COVID Crisis

Earlier this month, the Hofstra Labor Studies and the Center for the Study of Labor and Democracy in collaboration with Long Island Jobs with Justice and A.L.L.O.W. (Advancing Local Leadership Opportunities for Women) conducted a virtual forum addressing care work in the context of COVID-19. This discussion emphasized the financial and mental health challenges associated with all types of care work during this pandemic, and the immense need to address and resolve these issues in order to assist with a fair and sustainable economic recovery. Although the discussion is focused primarily on Long Island and New York, the problems indicated are applicable to care work throughout the U.S.

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that the unemployment or the stress of juggling work and home life as a result of the crisis has hit women much harder than men. This discussion utilized academia as an example of this, drawing upon data indicating that academic journal submissions have greatly increased among men since the beginning of the pandemic, but sharply decreased among women. For those working in academia, publishing work is crucial to professional advancement.

The pandemic has also shed a harsh light on the fragility of the overall childcare system in the U.S. Many families lacked adequate childcare even before the pandemic, forcing them to rely on unpaid care work. These existing issues paired with the recent closures of childcare facilities has exacerbated the problem.

Although the CARES Act did include childcare support, New York receiving $164 million going toward the childcare industry to provide protective equipment and cleaning supplies, the panel argues that while helpful those measures still did not provide adequate relief. The HEROES Act could potentially provide further relief for the care industry, but participants of this forum are less than optimistic about it providing the level relief needed.

The International Labor Organization estimates that three-quarters of unpaid care worldwide is provided by women. In the U.S. women provide 37% more unpaid care work than men on a daily basis. Among care providers in the U.S., Hispanic women do the majority of unpaid care and account for the biggest gap among men and women. Beyond traditional gender roles, this is largely tied to economics; oftentimes men have opportunities to make more money. But generally speaking, even when both parents work full time, women are still taking on more unpaid work even if they are earning more money than the male figure within the household.

There is also a societal tendency which expects care workers to be exceptionally giving. This is highlighted in the fact that even within paid care work positions, there is a fair amount of unpaid work being performed. For example, staying with an elderly person at their doctor’s appointment a couple of hours after the official workday has ended. This is a constant strain within the care industry, and COVID-19 has increased the pressure on this component of unpaid work within the paid care industry.

Additionally, the many racial and ethnic disparities within care work serve as a microcosm of larger racial inequities prevalent in society. For example, in New York, 80% of care workers are women, and a large majority of them are women of color. Furthermore, care workers in New York typically make minimum wage yet are still known to go above and beyond in their roles to ensure the best care is provided, regardless of whether or not it is part of their job description. This existing issue has been pushed to a new level due to COVID-19; now many of our care workers are putting their lives on the line.

Part of the reason that low wages are prevalent within the care sector is the historical association that care work is a “women’s job,” coming naturally and requiring little skillset. This sentiment in the U.S. is compounded by care work being viewed as the responsibility of the individual. The decision to have a family is viewed as a personal choice, therefore the basic needs of childcare are the sole responsibility of the parents, not something to be addressed via larger social safety nets.

New York is facing a particularly troubling dilemma within its care work industry. Despite the fact that a large majority of the workforce is comprised of immigrants, the guidelines that have been released outlining protection measures from COVID-19 are only available in English. This is concerning given that some workers may not yet possess the English language proficiency necessary to fully comprehend these guidelines.

In order to address these strains within the care work industry, political will and national policy are needed. The U.S. Department of Defense provides an exemplary model that could be emulated on a national scale. This government sector presently has one of the best childcare systems available in the U.S., operating on a sliding scale making it accessible to all those within the department that need it. This allows these federal employees to perform their duties with the comfort of this social safety net.

Furthermore, at the local level, immediate state, and county-level funding for care work can have a significant impact on the accessibility needed during this stressful time. Without swift action on the policy level, the issues discussed will continue and have detrimental effects on not only families, but economic recovery as well.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in COVID 19, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy, U.S.

The True Cost of Caregiving: An Aspen Institute Digital Discussion

Even in a typical year, U.S. households are estimated to experience $31.9 billion in lost wages as a result of inadequate childcare and paid leave. Roughly 1 in 5 people living in the U.S. today incur caregiving expenses, and the need for care work is experienced in nearly every household at least once. Those who are professional care workers, disproportionately women of color, are underpaid and therefore susceptible to financial insecurity. Those insecurities have been exacerbated even further amidst COVID-19 and the resulting economic downturn.

In June 2020, the Aspen Institute Business and Society Program hosted a digital discussion “Paid Leave, Livable Wage, Affordable Care: Policies that Could Avert the Next Crisis” in conjunction a policy brief “The True Cost of Caregiving” that was released in May. Within this discussion, the panel focused on the fragility of the care system and the financial stability of those providing care, both paid and unpaid. The panel not only addresses these issues but seeks to re-imagine a system in which care is treated like a public good, examines the hierarchy of human value, delves into the historical context behind care work in the U.S., the vulnerability of care workers in the current pandemic, and the inefficiency of the current care economy within the larger economic system.

A number of important questioned are addressed such as:

– How to quantify the benefits of paid leave, livable wages, and affordable care policies?

-What are feasible policy responses to COVID-19, in both the short term and long term, that can lead to better systems of caregiving in the U.S?

-What does an inclusive and equitable care system could look like?

-Who bears responsibility for building this system?

Further, this panel brings to the table the idea that care work should be invested in collectively as a nation, as opposed to being looked at as an individual burden; which puts increasing downward pressure on those who are already disadvantaged in the U.S. due to race and gender.

Policies that address these concerns could assist in not only building a more equitable system of care but have the potential to aid in averting future crises like that which the care economy finds itself in today.

- Published in Child Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy, U.S.

The Homemade Value-Added Stabilizer

“Shelter in place” mandates in the early stages of the U.S. Covid-19 pandemic required many people to stay home, cook their own meals, school their own children, and entertain themselves. Unpaid work served not only as a social safety net, but also as an automatic stabilizer. While it didn’t dampen fluctuations in official Gross Domestic Product, as did unemployment insurance, it clearly helped stabilize consumption.

Just imagine what would have happened if most people had not had refrigerators, stoves, and computers—or just read reports of the plight of homeless people.

By mid-March 2020, many states and localities shut down restaurants for any services other than take-out. Home-produced meals increased of necessity. Many such meals probably consisted of convenient processed foods that could be popped into a microwave oven, but a renaissance of home cooking also became apparent, along with reliance on long-lasting, easily stored items such as rice and beans. Analysis of Google Search terms showed a sharp spike in questions concerning food preparation and storage. As one newspaper put it, America began baking its heart out. Yeast suddenly became as hard to come by as toilet paper.

In 2018, according to the American Time Use Survey, adult civilian women spent an average of .8 hours a day, and their male counterparts .4 hours a day in meal preparation. How much more did they spend in the months of March and April, and what was the monetary value of this unpaid labor, based on what it would have cost them to hire someone to plan, cook, and clean up? How much did they save on eating-out?

Many childcare centers and schools were closed, leaving parents with responsibility for home-schooling, supervising children, and keeping them from going confinement-crazy. The American Time Use Survey averaged the amount of reported time that married mothers and fathers living with children under the age of 18 spent in primary activities of caring for and helping household children over the 2013-2017 period—an average of 2.6 hours per day for mothers not employed and 1.4 hours for fathers not employed.

Under sequestration, both active care and supervisory care (defined as the time in which an adult reported that a child under the age of 13 “in their care” ) ballooned. How much did these two forms of childcare increase? How much did households save on childcare costs?

Video streaming and gaming increased dramatically, especially during afternoon hours, and people began to rely more heavily on streaming for instruction and exercise as well as entertainment. So, while they spent less money (and less travel time) on entertainment away from home, they substituted forms of entertainment that were probably less expensive, on average. How much less expensive?

Between March and May, average household income plummeted as a result of job furloughs and unemployment. The increase in time devoted to household production buffered this loss to some extent—but without answers to the questions above, we can’t know how much. Most recent impromptu household surveys have focused primarily on women’s unpaid work relative to men’s—an important, but different topic.

For years, I have protested economists’ lack of interest in total consumption—defined as the sum of money expenditures and the consumption of home-produced services.

Let me will repeat one example that I have written about in more detail elsewhere: Compare two couples, each with two small children, each earning $50,000 after taxes. Conventional measures treat them as having exactly the same income. Yet one couple may include an adult earning $50,000 and a full-time homemaker/caregiver, while the other includes two adults earning $25,000 each and obviously has less time to devote to unpaid work. If we assigned any positive value to unpaid work, the first household would obviously be better off in terms of both income and consumption.

Market income is just not a very good indicator of total consumption among households with differing inputs of unpaid work. Also, the value of unpaid work is greater in households with more than one person, because of economies of scale in food preparation and childcare. Standard equivalence scales used to adjust household income for household size and composition completely ignore these issues.

Obviously, the additional unpaid work performed while sheltering in place was a source of great stress, especially for those simultaneously telecommuting, zooming, or otherwise trying to fulfill paid employment responsibilities at home. Yet, it’s hard to deny that this work also “added value,” enabling an important form of social provisioning.

The worst-case scenario for a household with children was almost certainly one in which all adults (e.g. mother and father) were essential workers, required to keep working (often at risk to their health) but unable to work from home. Federal and state agencies tried to provide “resources” for these workers, but no guarantees were forthcoming.

In many cases, one of the adults (probably the mother) was forced to quit or take a leave of absence from paid employment. While new federal legislation gives states flexibility to pay benefits where an individual leaves employment to care for a family member, not all states do so.

Such a policy is effectively a paid family leave—something that most states have shied away from for years, making this country an international outlier. The complexity of the new legislation, plus the difficulty of actually filing for and receiving unemployment benefits, has probably kept take-up pretty low even in states that allow this option.

Just one more reason to consider policies such as federal paid family and sick leaves and a universal basic income that could help the stabilizers known as households do their job.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on May 19th, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in COVID 19, Time Use Survey, U.S., Unpaid Work