Global Nonprofit Leaders on Why Women’s Time and Work Must be Part of Future Policy Choices

Last year, before the outbreak of COVID-19, the Hewlett Foundation teamed up with StoryCorps to record conversations with six nonprofit leaders working from Nairobi to Mexico City to make women’s lives, including paid and unpaid work, visible and part of economic policy decisions. Their professional endeavors—and personal motivations—help us see the different ways women experience day-to-day life, and are affected by social and economic changes, including the COVID-19 pandemic and prevention measures.

Maria Floro grew up in the Philippines and saw her parents treat her and her brother very differently. She was expected to help in the household work, including cleaning her brother’s room—something that nagged at her even when she was only four or five years old. Jenna Harvey watched her mother take on the majority of care work in her home and for her grandparents. It made her curious about gender and the unpaid work women do to make the world run.

Today, Floro is an economics professor at American University and runs Care Work and the Economy, a network of researchers interested in incorporating care work and gender into macroeconomic and social policies. Harvey is the global Focal Cities coordinator for Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing & Organizing (WIEGO). As a global network—with Accra, Dakar, Delhi, Lima, and Mexico City as focal cities—WIEGO helps street vendors, waste pickers, domestic workers, and other informal workers organize themselves and use research and analysis to urge local, national, and global policymakers to improve their working conditions and opportunities.

Memory Kachambwa’s first fight was with a boy on a bus outside her farming town near Harare, Zimbabwe. “Who appointed you to be captain of the bus?” she remembers telling him when he tried to take charge and told her to sit quiet. Today she runs the African Women’s Development and Communication Network (FEMNET) based in Nairobi. FEMNET’s 800 members in 46 African countries work to create an African society where women and girls live with dignity and equal rights.

In her StoryCorps conversation, Kachambwa speaks with Gretchen Donehower, who leads the Counting Women’s Work project at the University of California at Berkeley. As a teenager, Donehower told her mom she wanted to be the first female chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board. She now runs a global research project that has teams in 60 countries tracking how men, women, girls, and boys produce, consume, transfer, and save economic resources—including with a new tool developed to track this during the coronavirus.

Kachambwa and Donehower recall another health crisis that put a large extra unpaid care burden on women in sub-Saharan Africa: HIV/AIDS. Women, including grandmothers, were often the ones who cared for the sick and for orphaned children. Policymakers, they say, need to include the cost of women’s time caretaking to figure out how and where to allocate resources to respond to health and economic crises. The care economy, Kachambwa and Donehower agree, is part of the economy.

This blog was authored by Sarah Jane Straats from the Hewlett Foundation.

Original blog published by Hewlett Foundation on October 19, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Sarah Jane Straats.

- Published in Leaders in Non-profit, Special Issues

COVID, the Old and Canada-What’s Wrong With Us? A Massey Dialogues Discussion

A recent virtual presentation from Massey College, “The Massey Dialogues: COVID, the old and Canada – What’s wrong with us?” brought together a panel to discuss how the detrimental impacts of COVID-19 in Ontario and Quebec fall alarmingly onto the elderly population. In fact, 80 per cent of pandemic deaths in Canada have occurred among the institutionalized elderly, the highest proportion in the world.

Ito Peng joins this conversation as a special guest to discuss the pandemic and its impact on Canada’s Long Term Care (LTC) sector, and ways through which the dominant thinking around market value/productivity neglects to value the work that older adults have already contributed to the economy throughout their lives, and fails to recognize their role as keepers of history and caretakers themselves.

In this discussion, Ito Peng is joined by Massey Fellows Dorothy Pringle, Husayn Marani and Michael Valpy.

- Published in COVID 19, elderly care, Expert Dialogues & Forums

U.S. Needs to Save Child Care Before It’s Too Late

The childcare system in the US was already in a critical state of inadequacy, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made this worse. A recent report released by the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (JEC) – “We Need to Save Child Care Before It’s Too late” – explores the U.S. childcare crisis in detail, outlining the shortages in child care and the consequent economics effects of those shortages.

According to the report, as of August 2020, roughly 214,000 U.S. childcare workers were out of a job and 4 out of 5 childcare providers expected to close permanently if no public assistance is provided. This is of course having a trickle-down effect on the working parents that rely on this childcare, and 13% of parents reported having to reduce their working hours.

This issue is further compounded in the many areas throughout the country considered to be “childcare deserts” where the supply of childcare falls well below the demand and for many families is not accessible due to cost constraints. Although there are assistance programs available for those in need, such as the Head Start program, many of those that qualify still do not receive assistance due to severe lack of funding. In over half of states, childcare and early childhood education exceeds the cost of college tuition, and bearing this burden is extremely difficult for lower income families.

Middle income families that do not qualify at all for government funded programs are under even more strain with the financial obligations of childcare. Infant care is in particular incredibly expensive, and a median income family home could spend anywhere from 23% to 77% of their income on the care of their infant, depending on the state. For single mothers in the median income range, this could be from 29% to 94%.

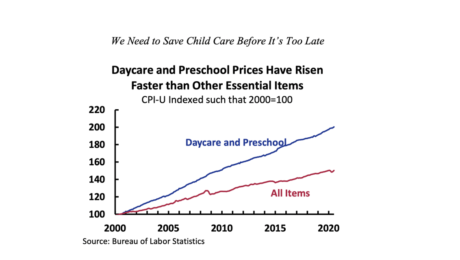

Childcare costs in the U.S. are exponentially higher than its OECD counterparts. The U.S. spends less that half the amount of its GDP on childcare in comparison to the average of other OECD nations. In fact, the U.S. spends 3 to 6 times less than France, New Zealand, and all the Nordic countries. Where in many OECD nations, childcare is free or very inexpensive, making it widely accessible, in the US, the accessibility and quality of childcare for working parents is contingents upon their economic status. A lack of accessible and affordable childcare leads to lost earnings for parents, an estimated $20 – $35 billion in total, according to the Economic Policy Institute. This in turn translates into a loss of roughly $4.2 billion dollars in federal and state tax revenue per year. The cost of childcare is skyrocketing past the rate of inflations as well, between the years 2000 and 2020, day care and preschool costs rose double that of inflation.

Extensive research has shown that accessible and affordable childcare has strong positive economic benefits and contributes to the well-being of children and parents. Without the benefit of accessible and affordable childcare, many parents, mostly women, experience reduced earnings for the duration of their careers. This also contributes tremendously to the gender wage gap. Furthermore, according to a 2015 Council of Economic Advisors report, every dollar spent on childcare and early education carries the potential to yield eight dollars in societal benefit.

Childcare workers also struggle due to low wages, poor benefits, and precarious working conditions. In 2017, an average childcare employer kept 13 workers on payroll, each of whom earned just $20,886 on average in annual compensation. In 2019, the median hourly wage of U.S. childcare workers was $11.65, a near-poverty wage. Nonetheless, employee’s compensation is the highest cost for these establishments, as they must maintain a low ratio of children to caretaker, which varies from state to state. Cost of rent is another major expense for childcare providers, but reducing the size of the facility, and therefore the rent costs, is not a viable option as crowding and lack of outdoor space has been shown to increase the risk of infections and injury within the centers.

There is still a great amount of work to be done in the U.S. The CARES Act passed in March of 2020 provided $3.5 billion of funding to states in childcare subsidies for low income families. Additionally, the inclusion of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) provided $2.3 billion to childcare providers across the country, enabling 460,000 childcare workers to remain employed. Although these measures were helpful, much more assistance is still needed. For the most part, smaller childcare centers and home-based programs were not able to access these PPP funds at all, with only 29% of them receiving these funds. The vast majority of childcare operations across the board, many of which single-person operations, were also not able to access these PPP funds at all. The HEROES Act, passed in the House of Representatives in May, would provide another $7 billion in relief for childcare centers and $850 to fund child and family care for essential workers. However, this legislation has stalled in the Senate.

This pandemic has dealt a devastating blow to an already inadequate childcare system in the U.S. Without desperately needed assistance, the U.S. faces the potential of losing 80% of its childcare capacity. This will in turn deprive working parents of the critical services and infrastructure needed for the economy to recover. Read the complete report “We Need to Save Child Care Before It’s Too Late.”

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Policy, U.S.

Spirals of Inequality: A Women’s Budget Group Special Report

The Women’s Budget Group Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy, launched in February 2019, is an expert-led project aimed at developing economic policies that promote gender equality across the United Kingdom. The Commission utilizes a number of avenues and tools to achieve this objective, one of which is the recent release of the report “Spirals of Inequality: How Unpaid Care is at the Heart of Gender Inequalities.”

This first report released by the Commission seeks to trace the problem of how gender inequalities in the UK are produced and maintained by observing the problem through the following perspectives:

Unpaid Work: Women Continue to do the Lion’s Share

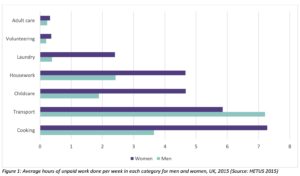

The unequal division of labor within unpaid care work is at the heart of gender inequality in the UK, with women taking on 60% of the unpaid work on average. This includes care work, cooking, and cleaning among other tasks.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

Limiting Opportunities for Paid Work: Women More Likely to Work Part-Time and Earn Less

This phenomenon puts a disproportionate strain on women and contributes to gender inequality. Mothers with young children are 3-4 times more likely to work part-time, and women, in general, are far more likely to be in precarious forms of employment such as temporary work. This is especially true for women of color. The part-time work conundrum is driving the gender gap, and on average women earn 43% less than men. Furthermore, a pay gap of 8.9% persists, further exacerbating this issue. Again, this being more predominate with women of color.

Despite women becoming increasingly educated, they persist in being overrepresented in low-wage sectors of the economy such as health and social work. Feminist economists have argued that a reason behind this is such sectors are viewed as an extension of a women’s “natural” work.

These issues create a perpetual cycle that allows for the inequality between men and women to continue.

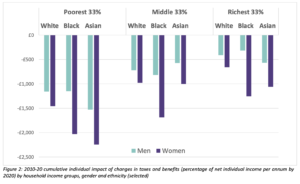

Life Course Implications: Benefits Make Up a Larger Portion of Income and Austerity Hits Harder

Among single households living in poverty, those led by women make up for 86%. Furthermore, pensioners living alone are far more likely to be at the poverty level if that individual is a woman. Since tax reforms began in 2010 throughout the UK, women have also been hit hardest. These benefits make up a large portion of women’s incomes and cuts to these benefits and tax giveaways benefit those fitting into a higher wealth bracket.

Public Services: Women Hit Hardest by Cutbacks

Cuts to public spending throughout the UK have also hit women disproportionately hard, as women are most likely to utilize public services. The poorest families and especially those in poverty-level households led by women have taken a particularly bad hit; many single mothers have had to cut living standards by up to 10% as a result of a cut to public services between 2010 and 2017.

Furthermore, these cuts have put a greater burden on family members to provide care for the elderly members of their family, much of this falling onto female members. This often comes at the expense of their own employment.

Violence Against Women: “Cause and Consequence” of Women’s Economic Equality

All of the factors that lead to the economic disparity between men and women also make it increasingly difficult for women to leave abusive partners. Furthermore, poorer households have higher rates of domestic abuse, and this perpetuating poverty limits women’s options while increasing their vulnerability.

Moving Forward: Next Steps for the Commission

The WBG Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy is striving to develop an alternative economic approach aimed at addressing these issues. Through this initiative, they aim to build an economy that is desirable, economically feasible, and necessary for fairness, sustainability, and resilience. To learn more about the Commission and its work, sign up to attend the upcoming webinar “Creating a Caring Economy: A Call to Action” on September 30, 2020.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy