Family Caregivers’ Elder Care: Understanding Their Hard Time and Care Burden

In response to the imminent aging problem in South Korea, the National Long-Term Care Insurance (NLTCI) system was introduced in 2008. The goal of the NLTCI was to give support to the families who are taking care of their elderly. The burden of family care can be grouped into four broad categories – unpaid and at home, paid and at home, paid and in facility, and unpaid visit of the family when care recipient is in facilities. Moon et al (2019) focus on the challenges faced by providers of unpaid care within families – unpaid care by family members is the most prevalent form of elderly care in Korean society.

Korean’s attitudes or thoughts on the family care responsibility of their old parents have changed surprisingly as time passed. In 1998, 89.9% of Koreans agreed with the idea that the care responsibility of their old parents belongs to the family. In 2014, the figure dropped to about a third of the population – only 34.1% of surveyed adults agreed to share the responsibility. The authors take this trend and generational gap as the departure point for their qualitative analysis of the difficulties faced by caregivers, with a view that there might be a clash or inconsistency in the care behaviors of the family members or in their ways of thinking on elderly care.

Using a combination of oral history and in-depth interviews, Moon et al (2019) shed light on the increasing burden of labor force participation and aging parents and in-laws on Korean women. Many elderly persons need attention and care continuously for 24 hours – in this regard the public care service providers provide limited relief as they work for only three hours at a time. In addition to the public-private and paid-unpaid differences in the burden of care, the authors draw attention to the difficulty of deciding who in the family takes up the responsibility. In many cases, the traditional caretaker roles fulfilled by the daughters-in-law have shifted to the daughters of the elderly. Social norms also contributed to the disproportionate caretaking burden borne by women.

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

Care Arrangement and Caregiving Activities in South Korea: An analysis of 2018 Care Work Family Surveys on Childcare and Eldercare

The rise of the care crisis in South Korea has evolved with Korea’s demographic shifts, increasing female work force participation, and changes in the norms and values of family and care over previous decades. Childcare and eldercare, once regarded as women’s typical role within family, are now gaining more social recognition in the public realm. Kang and Eun (2019) examine the nature of, and demand for, caregiving in various areas of the South Korean economy, including family care, care services, childcare and eldercare. The study is based on the nationally representative Care Work Family Surveys on Childcare and Eldercare.

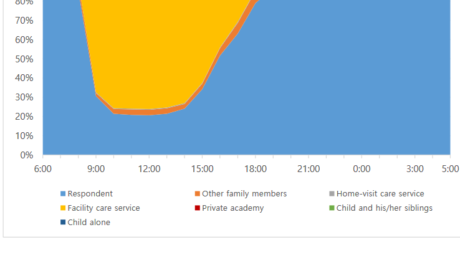

The authors find a significant gap between the number of hours spent on childcare by mothers and fathers. A majority of respondents (women) used at least one external care service. Among caregiving activities, housework such as preparing meals, cleaning, and laundry were reported as the most difficult as well as the most frequently performed activities. Relational and physical activities such as helping to dress, wash, or play with children were reported as less difficult. Caregiving for the elderly can be more complex compared to care arrangements for children, because the range of participants in the family varies. Among all respondents, daughters-in-law were the primary caregiver in the greatest number of cases, followed by daughters, spouses, and sons. Spouses spent the highest number of hours on caregiving, followed by daughter in laws. External care services were not as common for elderly care. Home visit care and home bathing services from the National Long-Term Care program were the most commonly utilized services, although the 3-hour limit per visit amounts to a low amount of total caregiving time. Assisting with bathing and using the restroom was considered especially difficult for the elderly. Housework was performed with the same intensity and frequency in both childcare and eldercare, highlighting the important role it plays in both.

This paper will be available December 2019

This blog was authored by Eunhye Kang and Ki-Soo Eun

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

Measuring the Overall Strain of Caregiving: A Multidimensional Approach

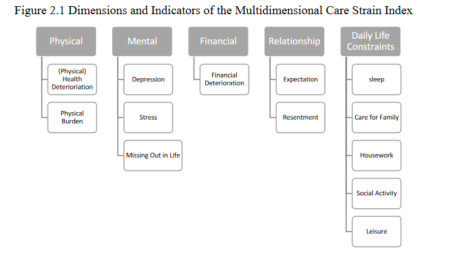

Providing care for others, especially for the frail elderly and young children, is one of the most important forms of human work that sustains our existence. However, caregiving is also often challenging and strenuous. Many informal caregivers are known to suffer negative physical, emotional, and social outcomes, and are at risk of losing their own health and well-being. Fengler and Goodrich, for example, refer to the wives of frail elderly men as ‘the hidden patient,’ warning the negative consequences of caregiving on informal caregivers. Since the 1980s, several instruments have been developed to measure the strain of caregiving among informal caregivers. Some measurements such as the Zarit Burden Interview and the Caregiver Strain Index have been applied more widely, while other measurements have been used for more specific groups of caregivers (e.g., who takes care of the elderly with cancer). Although these measures provide valuable information on various dimensions of caregiver strain, they are not sufficient to assess the overall level of strain experienced by caregivers. In most cases, these measurements consist of a list of questions or statements about the caregiver’s burden; the sum of the answers is then used to indicate the level of burden/strain experienced by the caregiver. Although useful, a simple non-weighted sum of answers may not be an accurate representation of the overall strain. For instance, two groups of caregivers may have the same average total strain score, but one group may consist of all caregivers who suffer strain in some statements, while the other group may have half of the care givers who suffer strain in all statements and the other half who do not suffer strain at all. While the marginal distribution may be the same, the joint distribution may not, and this has an important policy implication.

Adapting the Alkire-Foster method developed to measure multidimensional poverty, Jun et al (2019) propose a threshold-based approach to measuring overall caregiving strain that accounts for the multidimensionality of the caregiving experience. The approach is based on the premise that as in the case of poverty, the negative consequences of multiple strains attached to caregiving would be greater than the sum of their individual effects. The authors first identify the dimensions and indicators that are known to be important consequences of caregiving, such as physical, psychological, financial and relational strains, and daily life constraints. They then count the overlapping strains a care giver experiences under different indicators of caregiver strain. Next, they identify caregivers who are experiencing strains above a specific cut-off point as multi-dimensionally strained. This measure is tested using the data from the newly collected Survey of Eldercare and Childcare in Korea 2018, exploring whether receiving support, help and appreciation may be associated with reduced chance of being multi-dimensionally strained. By providing an overall measurement that identifies caregivers with multiple strains, the authors examine 1) which group of caregivers are more likely to be at risk; 2) which dimensions do most caregivers suffer strain; and 3) what may be potential buffers for caregiving strain.

This paper will be available December 2019

This blog was authored by Jiweon Jun, Ki-Soo Eun and Ito Peng

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

Methodology for Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea

Care work, whether unpaid or paid, lies at the heart of humanitarian concern and expression, and our societies and economies are dependent on it to survive and thrive. Across the world, women account for more than three-quarters of the total amount of unpaid care time while two-thirds of paid care workers are women (Folbre et al. 2012; ILO 2018; Yoon et al. 2011).The outsized role that women play in providing care is readily observed in South Korea, with its strong patriarchal and familistic orientation that assigns primary responsibility for the care of children and elderly to women in the household, reinforcing the economic significance of gender. While unpaid care work by family members, especially women, makes up a large part of the care provided within Korean society, the rapid aging of the population and the fact that more than 50% of the female population aged 16 and older participated in the labor force in 2016-18 underscore the importance of paid care workers in meeting care needs(ILO 2018).They tend to the most basic necessities and help sustain the well-being of those in dependent positions, such as children, frail elderly, or people with illness and/or disabilities. Broadly, there is a spectrum of paid workers providing care, ranging from informal workers such as domestic service workers, nannies, and home care aides in private homes to formal workers in child care centers, nurseries and early childhood learning centers, elder care centers, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities, to nurses and teachers.

Accounting for the contribution of paid care workers is crucial to our understanding of the centrality of care in the development of human capabilities and economic progress; itis a crucial part of the effort to make women’s work and all forms of care work more visible. As the ILO (2018) points out, “care workers close the circle between unpaid care provision and paid work” (p.166). It is also critical to understand their work conditions since they represent one of 5the fastest growing segments of the labor force. For that reason, it is of particular concern that the paid care workforce experience slow wages and difficult working conditions across occupations and industries (ILO 2018). For instance, domestic workers are most vulnerable to exploitation and abuse among all workers in the labor market (UNDP 2015), a consequence of their frequent exclusion from laws and regulations affording labor protections. Understanding paid care work is therefore critical to shedding light on the implications of economic, cultural, and policy contexts that shape the larger labor market as well.

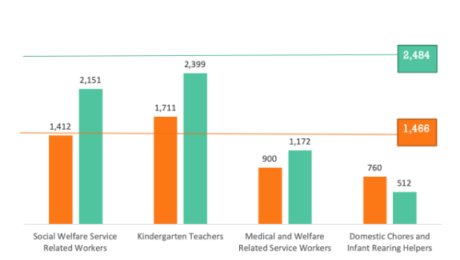

Suh (2019) provides a comprehensive picture of the paid care workforce in South Korea by measuring its size and extrapolating the median wage earnings and aggregate hours spent on care-giving by the workers using following data sources: the Local Area Labor Force Survey, Child Care Statistics, Social Services Voucher Statistics, and Long-term Care Insurance Statistical Yearbook for 2009 and 2014. The size of the paid care workforce in South Korea in this estimation focuses on the value of the labor provided by care workers that are directly and indirectly involved in elder care and childcare provision. The estimation will be used for making the paid care sector visible in the Korean Social Accounting Matrix (SAM), which serves as the base for developing the GAM Care Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model for policy analysis.

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

Methodology for Estimating the Unpaid Care Sector in South Korea

Mainstream economists continue to define economic growth in terms of conventional measures such as market employment and income per capita. Women’s taking on full-time employment outside the home, therefore, has stimulated Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth, while the social cost of a shift from informal to the formal economy has been ignored. The importance of fully recognizing the economic contributions of all forms of work –paid and unpaid–as a precondition for achieving gender equality has been proposed by feminist researchers since 1980s (Waring 1988, Folbre 1991). They have emphasized the need for empirical analysis of time devoted to unpaid care work, especially direct care of children, adults in need of assistance because of illness or disability, and the frail elderly.

Unpaid care work, i.e. household production, is the most significant part of production which is excluded from the production boundary of the system of national accounts(SNA) and hence, from the most commonly used economic indicator, Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The failure to recognize the economic value of unpaid care work leads to the belief that people who, without compensation, devote time to caring for others are unproductive or inactive and their unpaid activities fall outside the business of economic life. To be sure, unpaid household services and care work are now recognized in the landmark resolution for defining and measuring work passed during the 19th International Conference of Labour Statisticians (ICLS) in 2013. Nevertheless, the lack of recognition of unpaid care work in the national accounts hinders the promotion of gender equality at the macroeconomic level due to the importance of these accounts as instruments for policymaking.

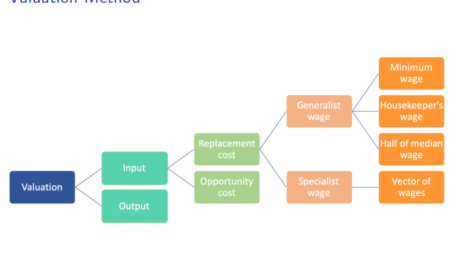

Suh (2019) first explores the concept of unpaid care work and its two forms, direct or relational care activities and indirect care activities. It then examines the role of time use data in estimating the unpaid, direct or relational care labor time provided by household members and the various methods by which this form of unpaid care work can be measured and valued, highlighting methodological and measurement issues. The input-based approach is then applied to the estimation of the imputed value of unpaid care provided by women and men aged 18 years and older based on the national Korean time use survey data and the Korean Labor Force survey for 2009and 2014. A range of wage rates is used for the estimation and differences between women and men are highlighted. These estimates are then aggregated for the population of South Korea. Finally, the paper concludes with a brief commentary on the importance of measuring and valuing unpaid care work.

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

An Overview of Care Policies and the Status of Care Workers in South Korea

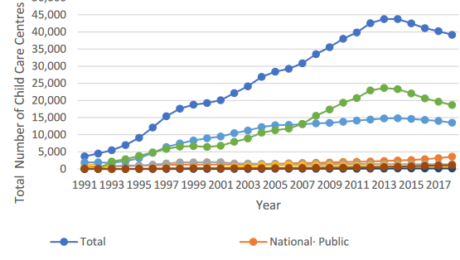

The last couple of decades have seen a dramatic transformation of the care infrastructure in South Korea. This is evident from the introductions of successive government policies and programs to socialize care and to address the issue of work-family balance. These new policies and programs have resulted in a steady expansion of publicly funded and publicly or privately provided care services for children and the elderly, financial support for families with young children, and family support programs such as maternity and parental leaves and family care leaves. Although there has been a significant amount of research on child and elder care policies in Korea, not as much attention has been paid to the status of care workers. This is unfortunate particularly given that social care expansion in Korea has been one of the most important drivers of employment growth in the country for the last decade and a half.

Peng et al (2019) provide an overview of care policies in South Korea and their developments since 2000 and discuss the status of care workers in the context of the current care infrastructure. They focus on paid childcare and elderly care as much of the country’s current care policies are directed to these two sectors. A broad overview outlines the current care policies and systems, including some data on the number of people who are affected and serviced, and some of the immediate causes of the government’s policy focus on care and of social care expansions and reforms. Recent developments in Korea’s care policies illustrate a path of progressive and successful socialization of care that has yielded a significant employment generation, particularly for women. Despite the progress in social care, however, available data suggest that the working conditions and status of care workers in Korea are not very positive: women dominate care work in both child care and elder care, and care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and their employment is precarious. Care work is also accorded with low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress.

The authors conclude by discussing the implications of South Korea’s current care infrastructure for gender equality and the care economy. To better understand the nature of care work and the status and situations of care workers, and Korea’s care infrastructure, they call for more in-depth data collection on care workers as well as more comprehensive measures of care

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The case of South Korea

According to the Global Gender Gap Index of the World Economic Forum (2018), South Korea is one of the lowest ranked countries in the world in terms of “Economic Participation and Opportunity” (124th out of 149 countries) as of 2018. The Global Gender Gap Index also shows that South Korea ranks 88th in terms of female labor force participation and 121st in terms of gender wage equality for similar work. The average wages of women in South Korea are on average 36.7% lower than average male wages (as of 2012, own calculations based on World Klems (2014) database). These statistics reflect that there is a significant economic gender gap in South Korea despite the fact that the country is now classified as a high-income economy. Moreover, the underdeveloped care infrastructure and reliance on unpaid care labor of women is posing serious demographic and social sustainability challenges in an aging society.

Existing research on the effects of public spending show a stronger positive effect of public spending in social care and education on female employment as well as total employment compared to public investment in physical infrastructure (Antonopoulos et al., 2010; Ilkkaracan, Kim and Kaya, 2015; Ilkkaracan and Kim, 2018; De Henau et al., 2016; Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou, 2019a). These employment effects have further effects on the economy and the wellbeing of the society, as microeconomic studies across the board attest that a larger share of women’s income compared to that of men’s, is spent to satisfy the needs of the household (Blumberg, 1991; Antonopoulos et al, 2010; Pahl, 2000) and a possible increase in their income leads to increased spending on children’s education and wellbeing (Vogler and Pahl, 1994; Lundeberg et al. 1997; Cappellini, Marilli and Parsons, 2014). Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou (2019a) confirm this finding at the macroeconomic level for the case of the UK. These consequently have further demand and supply side effects on output, productivity and employment (Onaran, Oyvat and Fotopoulou, 2019a; Seguino, 2017).

Oyvat & Onaran (2019) examines the short-run and medium-run impact of public spending in social infrastructure, defined as expenditure in education, childcare, health and social care on aggregate output and employment of men and women for the case of South Korea. They present a gendered Post-Kaleckian theoretical macroeconomic model. The authors estimate the macroeconomic effects of social expenditure using a vector autoregression (VAR) analysis for the period of 1970-2012. The results show that an increase in the public social infrastructure significantly increases the total non-agricultural output and employment in South Korea both the short and medium-run. Moreover, higher social infrastructure expenditure increases female employment more than male employment in the short-run and raises both male and female employment in the medium-run due to increasing aggregate output. Finally, estimates show that the South Korean economy is wage-led and gender equality-led in the short-run, hence overall equality-led, although the effects are economically small in comparison to the strong effects of increases social infrastructure spending, and become insignificant in the medium-run. The results indicate that sustainable equitable development and a substantial increase in employment requires a mix of both labor market and fiscal policies.

This paper will be available December 2019

- Published in Gender-Aware Macromodels, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea

The Provision of Elderly Care and the Macroeconomy

The dramatic increase in life expectancy in most developed and developing countries over the last few decades has led to renewed discussions around elderly care policy options, and the debates are expected to intensify as the ratio of elderly to working-age adults continues to rise. According to United Nations, the share of people aged 60 years or over is growing faster than all younger age groups. Older segments of the world population are expected to double by 2050 and to more than triple by 2100. In addition to these demographic shift, contemporary societies are still characterized by prevalent gender inequality. One aspect of gender inequality is the unequal intra-household division of labor, which is particularly important for the analysis of care policies: women still do most of the unpaid care work.

Brun et al (2019) develops an overlapping-generation model to analyze the economic effects of increasing elderly care needs and evaluate different care arrangements, including the prevalence of unpaid care work. They model the demand of care as being complementary to elders’ consumption. This complementarity increases over time, as retired households become older, making the demand for care more inelastic. They analyze how increasing care needs affect key economic aggregates, such as savings, the gendered provision of paid and unpaid care, and the female labor market participation. Finally, they use the model to study the effects of the secular increase in women’s labor supply that took place between the 70s and the 90s on the provision of care, and evaluate alternative social arrangements, e.g. market-based vs publicly provided care, that so far have only partially replaced the unpaid care traditionally provided by women.

The paper will be available December 2019

- Published in Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea

Bringing Together Research, Civil Society, and Policy Communities to Advance the Policy Discussion on Care in South Korea

Hyun Lim Lee, kindergarten teacher and organizer for the Childcare Workers Chapter of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, stood in front of the room full of civil society organization representatives and Korean and international researchers. She is passionate about her job as a kindergarten teacher and passionate about the need to improve working conditions for caregivers in South Korea. She told the group about the challenges she faces as a kindergarten teacher, explaining how the high child-to-caregiver ratio and long hours without breaks make it difficult to provide quality care. She shared how low pay and poor benefits have made it challenging to attract and retain early education teachers in the country. Lee is one of 35 participants who came together on February 25, 2019 in Seoul, South Korea to kick-off a new project led by Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) and its partner Seoul National University (SNU). The event brought together organizations working to support the power of care workers in South Korea with researchers from academia and the government to discuss the issues and challenges in getting care on the policy agenda to promote informed policies that enhance the quality of life of both those providing and receiving care.

Hyun Lim Lee, kindergarten teacher and organizer for the Childcare Workers Chapter of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, stood in front of the room full of civil society organization representatives and Korean and international researchers. She is passionate about her job as a kindergarten teacher and passionate about the need to improve working conditions for caregivers in South Korea. She told the group about the challenges she faces as a kindergarten teacher, explaining how the high child-to-caregiver ratio and long hours without breaks make it difficult to provide quality care. She shared how low pay and poor benefits have made it challenging to attract and retain early education teachers in the country. Lee is one of 35 participants who came together on February 25, 2019 in Seoul, South Korea to kick-off a new project led by Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) and its partner Seoul National University (SNU). The event brought together organizations working to support the power of care workers in South Korea with researchers from academia and the government to discuss the issues and challenges in getting care on the policy agenda to promote informed policies that enhance the quality of life of both those providing and receiving care.

Society Cannot Exist Without Care. The Economy Cannot Exist Without Care.

As Ito Peng, Professor at the University of Toronto, stressed at the February 25 kick-off conference: “Society cannot exist without care. The economy cannot exist without care.” Caring for children, the elderly, and other dependents is a vital form of work that sustains human existence, enhances individual and broader societal well-being, and promotes sustainable development. Despite producing tremendous benefits for individuals, families, and communities, care work is enormously undervalued. Peng’s concluding remarks at the conference highlighted how “we often say care is invisible, but what care workers shared with us at today’s conference shows that care is actually very visible – care is being provided all the time – it is just something people refuse to see.” This leaves paid formal caregivers, like Hyun Lim Lee, feeling underfunded and overstretched. And informal family caregivers, who are mostly women in South Korea and around the world, are left struggling to balance their care responsibilities with working conditions and career paths that tend to ignore other, non-work obligations.

CWE-GAM, a network of over 35 researchers, is producing new data and empirical evidence and developing policy tools to advance our understanding of care work, care arrangements, and policy impacts on growth, distribution, and gender equality in South Korea. The project has undertaken a national survey of paid care workers (600 respondents) that includes a 24-hour time use diary, a nationally representative household survey of families responsible for caring for children and/or elderly (1,000 respondents), and in-depth interviews with caregivers and care recipients (90 respondents). The research will provide rich information on paid caregivers – illuminating their working conditions, well-being, and providing detail on the types of activities they undertake. The research also will provide robust data on families in South Korea and how they arrange, provide, and share care responsibilities within the household. A signature output of this work is the development of new macroeconomic tools to guide decisions on fiscal policies and public investments to reduce and redistribute unpaid care work. The project will use our new data in conjunction with existing data to develop a macroeconomic model of South Korea that incorporates care to allow for a more comprehensive understanding of how specific social and economic policies impact economic, welfare and distributional outcomes.

To ensure that this research is used to inform policy design, implementation, and evaluation, CWE-GAM’s new project will convene civil society organizations, researchers, and policymakers over the next year. The first conference on February 25 developed a strong dialogue between care and women’s rights focused civil society organizations, the broader research community in South Korea, and researchers concerned with issues of care and women’s and care workers’ rights internationally. Representatives from more than 12 civil society organizations and researchers from four distinct universities as well as institutions like IOM Migration Research and Training Centre, Korea Women’s Development Institute, Korea Institute of Child Care and Education, and Population Association of Korea spent the day together to articulate and better understand the challenges facing South Korea in providing quality care as well as the challenges care workers face, ranging from issues related to well-being in their jobs to job and income insecurity.

The meeting was an incredible first-step in a long-term commitment to bring together research, civil society, and policy communities to advance the policy discussion on care in South Korea. Over the next year, the CWE-GAM team, led by SNU, will convene several small group workshops around the country and will host two more interactive conferences as well as a high-profile policy dialogue in Seoul in the Spring of 2020. The aim of the engagement is to:

-

- Support the strategic use of our research and build the capacity of groups to use research more effectively;

- Provide insights into the production of our research outputs and research-based materials; and

- Share research findings, policy recommendations, and strengthen relationships among groups and between the civil society, research, and policy communities;

The project aims to build connections among and between these communities. The hope is that working collaboratively to ensure we are producing the data and research needed by those on the frontlines working to change policy and practice will lead to more informed policies that better address the needs to those providing and receiving care.

- Published in South Korea

Current Policies and Programs Addressing Childcare and Eldercare in South Korea

South Korea has experienced rapid economic growth and accelerated industrialization and modernization within a relatively short period of time in the seventies and eighties (Jang, 2009). Social policies were heavily oriented in supporting the government’s development strategies in terms of increasing human capital and improving health through public investment in these sectors (Song, 2014). Through most of that period, families were encouraged to carry the entire burden of care work and childrearing responsibilities, and social policies played a minimal role in sharing this burden, being mainly targeted to very limited low-income groups. Furthermore, filial piety, called hyo, one of the Confucian ideologies that served as a dominant foundation of state philosophy before the modern era of South Korea, remained even after the establishment of modern government and functioned as an essential foothold in determining care responsibility, unloading it entirely to the family (Lee, 2017).

However, demographic shifts, government regime change, and democratization process highlighted the need to address issues of redistribution and welfare and the important role of the state. The concept of the state serving as the main care provider is now gaining more attention, with its importance highly underlined in the current era of low fertility rates and an aging population in South Korea. In response to increased social awareness and demands, the South Korean government has shown efforts to revalue care work and reach a range of families’ needs.

The major care policies that South Korea currently has in place are:

- the Early Childhood Education and Care Policy,

- the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) Program,

- the Maternity Protection Act, and

- welfare policies for the disabled.

Gilbert and Neil (1974) in their book Dimensions of Social Welfare Policy introduced the idea that social provision can be divided into several types; power, cash, vouchers, time, services, and opportunity. The order of each type represents the degree of freedom of choice; for example, cash represents more freedom of choice compared to services. South Korea’s social and family policies have shown preference for expanding government provided care services, rather than developing social provision in the form of time or cash benefits. However, after recovering from economic crisis (1997-1998) and welfare reform (1999-2001), the Korean government has assumed greater responsibility by legislating, financing, and providing welfare, particularly childcare and elderly care, in public sectors, community level/local government sectors and also supporting the private care market sector. Promoting more care services supported the creation of more jobs in the care sector and allowed unpaid caregivers/housewives to enter labor force as paid careworkers.

South Korea’s social policy has gone through dramatic reforms recently, with the government moving its focus beyond the expansion of existing services towards creating policies (in the form of parental/emergency care leave as well as vouchers and allowances), which provide not only services but also financial support to households who take care of dependent family members on their own.

Currently the basic model for childcare in South Korea is to provide government-supported daycare (9:00 am to 4:00 pm) and education for all children from the ages of 0-6 years. When the model was first introduced, there were several blind spots and families’ needs were not always met. For example, early morning and late-night care (i.e. after 5:00 pm) was not provided. Korean society is notorious for long workhours for employed individuals, and the model doesn’t allow many dual-earner parents to both remain in full-time employment or the model requires them to find additional, often costly, care services. Over the last few years off-hours (7:00 am to 10:00 pm) care services were created and expanded to meet these unmet care needs. In addition, to prevent sole-care burden (“독박육아”, dok-bak-yook-a) among those who raise children alone at home, community-based childcare services for unpaid caregivers (e.g. housewives) were developed by local government subsidies. The prime objective of this service was to create a space for sharing childcare information within the community; engaging in education and entertainment together; and for lessening the burden of care, through services like childcare centers and co-parenting cafés.

Although the government (both central and local) expanded social policy significantly and provided huge amounts of subsidies for these services, several policymakers and researchers point out that parents or caregivers still feel burdened with care for their children and a great proportion of the expenses are still paid by the users.. For most social services, middle-class families are not eligible or only receive partial benefits since these programs mainly target low income families.

Even though the government has expanded social welfare programs since 2000, this was not in effect to impact the fertility rate. Therefore, the service-based childcare model has brought about discussion and debate in South Korea, as people tend to recognize that public services cannot meet the various needs of every family in the country. For example, for child care services, there has been debate on whether or not it is good for young children to stay 7-10 hours in a daycare center. Some scholars have also argued that there is a need to support caring for children “at home” or providing services in a “home-like” environment (Lee and Kim. 2011).

South Korea is also facing a “parental rights movement”, with advocates promoting family time and quality time for caring for children. Providing “time” for parents is the solution they feel will help parents the most. To provide higher flexibility for dual-earner parents who at the same time want to take care of their children by themselves, the government has pushed for a full year paid parental leave program. This was designed to give additional leave to parents who get 90 days maternity leave (fully paid) if they give birth. Both employed mothers and fathers can use full year parental leave until one child gets to age 9, respectively. This leave program guarantees about 50% of personal monthly income (although there is a ceiling for the income compensation). Although this full year parental leave program started in early 2000, it had been rarely practiced, as employers and sometimes even employees were reluctant to use it. However, to boost the low fertility rate, the government is now pushing for parents with young children to actually use this program. This is done by subsidizing (relieving company tax, spending direct financial funds), both in public sectors and private companies. According to labor statistics (2017) only 34,898 mothers and 502 fathers used parental leave in the year 2009, while, in 2017, the number of parents using the leave almost doubled for mothers (78,080) and increased dramatically for fathers (12,043).

In addition to parental leave policies, a financial benefit (age 0-5 years) starting from July 2018 will be provided to families with young children, with the eligibility set by their income level.

Compared to childcare, eldercare provision in South Korea has a shorter history. In 2008, the issue of eldercare gained greater attention, due in large part to the rapid growth of the elderly population and increase in life expectancies. A state-supported model of eldercare was developed as a result. The primary eldercare provision comes from long-term care insurance (LTCI), which allows all elderly with care needs access to non-live-in domiciliary (e.g. home helper services) and community and institutional-based care services, delivered by public and/or private for- and not-for-profit service providers. Unfortunately, the LTCI covered only 7.5 percent of total elderly population (age 65+) in South Korea, according to 2016 statistics (retrieved; http://www.longtermcare.or.kr/npb), while in Japan the eligibility rate is 18.4% and 15.2% in Germany. Despite the low percentage of elderly reached, 2017 statistics show that available eldercare services (both in-home service and institutional- based service) are being used by eligible beneficiaries, 84% and 64% capacity rate. Those who are not eligible for the LTCI are able to access comparable elderly care services within the community-based elderly care providers, which are partly supported by public voucher service, but mostly the cost is paid by individual families (Oh 2014: 1166).

Unlike childcare provision, where not only services but also time and money are given to families with young children, the South Korean eldercare model focuses more narrowly on direct service provision. The LTCI sometimes financed a family member who cares for dependent elderly parents if the adult child acquires a certificate of qualification for in-home eldercare, which is very rare. This feature was introduced to support elderly care in rural areas where in-home care workers or facilities are scarce. Meanwhile, it was expanded, later on, to urban areas (Yoon, 2014) to encourage some unpaid family caregivers to obtain care certificates that enable them to take care of their own parents in a more professional settings and earn a small income. Recently, however, the government announced that they will cut down on such family allowances, which could cause a devastating situation for those family caregivers. In order to compensate their income loss, it will be necessary to get a second job as a care provider and care for other non-family members or seek part-time jobs.

In regard to out-of-pocket expenses, even those families who are eligible for the LTCI benefit are required to pay a copayment. Currently, LTCI covers about 80% for institutional care and 85% for in-home-based care (copayment 20% and 15% respectively). Adult children’s income, commonly from paid full time and part-time work, is needed for caring for their elderly parents, which might drain their time available to care for their parents. Moreover, last year in 2017, the Korean government raised the LTCI payment rate (insurance fee) as well as the copayment rate due to the wage increase for paid caregivers in the LTCI sector, which will likely reinforce the issues described above. Yet, the government announced that they will support low to middle income families by subsidizing the out-of-pocket cost.

In terms of providing leave for caring for dependent elderly, this is much more limited than cash allowance policies. Employed individuals could apply for leave (full 90 days) for a limited period to take care of their parents. However, family leave for eldercare is mostly unpaid, which is very different from parental leave that provides partial income. The low fertility rates among young couples in Korea encouraged policymakers to adopt family-friendly parental leave policies. Unfortunately, although demographic shifts in Korea are a concern (the country is the world’s fastest-aging developed economy), policymakers have not felt the same incentives and pressure to create comprehensive leave policies to enable families to take care of dependent elderly on their own.

As the preceding discussion demonstrates, developing care models in South Korea has been a continuous process, with the government creating policies in quick response to urgent issues and challenges of the time. Despite the expansion in social care provisioning there remains questions of their impact on care recipients and their families. We have little information on how families navigate through the public and private care provision and make decisions about caring for dependent children and elderly family members. The issue of how families choose among different care delivery arrangements and to what extent they are able to combine public provision with their own private resources (i.e. time and money) to meet care needs has not been addressed. To date, little is known on how paid caregivers and unpaid family members develop relationships and emotional bonds with care recipients (i.e. child or elderly), and the linkages between paid and unpaid care work.

We argue that, without a comprehensive framework and a strong view on care, welfare and development, care policies in South Korea have yet to achieve the requisite level of recognition and effective utilization. There is still room for improvement to better meet the needs of families and redistribute responsibilities of care between private households and the public.

This blog was authored by Seung-Eun Cha, Hyuna Moon & Eunhye Kang

References

Kang, Young Wook (2002). Historic Review on the Changes of Infant Rearing Policies. Korean Public Administration History Review 11: 293-332.

Choi, In-Duck. (2014). A Study on the co-payment and the effect of long-term care insurance utilization by income level and region type. Journal of Community Welfare. 48: 135-164.

Hwangbo, Young Ran. (2014). A Historical review of the infant and child care act: Based on the characteristic of the law and the law system. Journal for Early Childhood Education and Care 9(2): 125-146.

Jang, Kyung-sup (2009). Family, Life course, Politics and Economy: Compressed Modernity Seoul: Changbi.

Kim Eun-jeong and Lee Hye-suk. (2016.) Evaluation of the Impact of Child Care Subsidy Program. Korean Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

Lee Meejin. (2017). Change on the family structure and policy for elderly care. Social Welfare & Social Work, 219:20-28.

Lee Seungmie and Kim Seonmi. (2011). A Basic Study on Public Nanny Service Characteristics and Improvement Strategies. Family and Environment Research 49(4): 51-65

Na, J. and Moon, M. (2003). Integrating Policies and Systems for Early Childhood Education and Care: The Case of the Republic of Korea. Early Childhood and Family Policy Series.

Oh, Young-ran. (2014). “A Study to establish social safety net of Elderly LTCI : Implication from the community inclusive care in Japan. Critical Social Welfare Academy Conference Presentation Paper. October 2014. 1166-1185.

Peng, Ito. (2009). Paid Care Workers in the Republic of Korea. UNRISD Research report 4, New York, UNRISD.

Peng, Ito. (2011). The good, the bad and the confusing: The political economy of social care expansion in South Korea. Development and Change, 42(4), 905-923.

Song, Da-young. (2014). Socializing of Caring and Delay of the Welfare State in Korea, Journal of Korean Women’s Studies 30(4):119-152.

- Published in Policy, South Korea, Understanding and Measuring Care

- 1

- 2