How Will COVID-19 Affect Women and Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries?

Policymakers should be thinking—and worried—about how COVID-19 is expected to disproportionately affect women and girls. Gender inequality can come into even starker focus in the context of health emergencies. With COVID-19 continuing to spread, what do we see so far—and what can we expect in the future—in terms of the impacts on women and girls?

Wenham, Smith, and Morgan discuss gendered impacts in their article, “COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak,” in the Lancet. Women appear to be less likely to die from COVID-19: “Emerging evidence suggests that more men than women are dying, potentially due to sex-based immunological or gendered differences, such as patterns and prevalence of smoking.” But keep in mind that “current sex-disaggregated data are incomplete, cautioning against early assumptions.” In other research, data from 1,000+ patients in China show that “41.9% of the patients were female.” (Guan and others 2020). But beyond these direct effects, most of the other impacts affect women negatively and disproportionately.

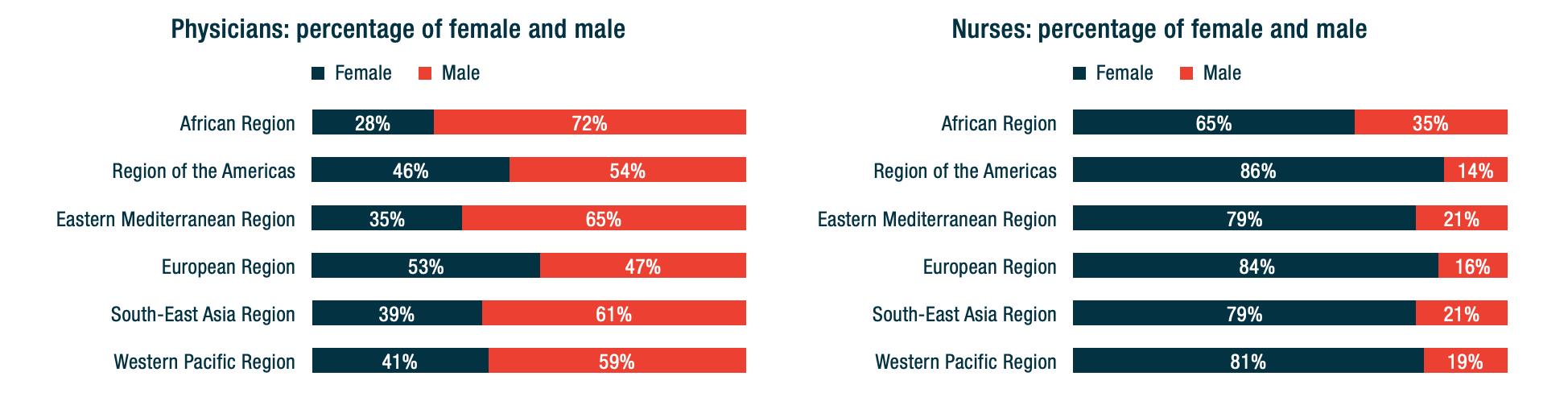

Wenham, Smith, and Morgan highlight that women will be more affected in places with more female health workers. In an analysis of 104 countries, Boniol and others (2019) show that women form 67 percent of the health workforce (see the figure below). In China, “an estimated 3000 health care workers have been infected and at least 22 have died” (Adams and Walls 2020). As the pandemic spreads, the toll on women health workers will likely be significant.

Figure. Gender distribution of health workers across 104 countries

Source: Boniol and others (2019)

Here are other areas highlighted by Wenham, Smith, and Morgan:

– School closures are likely to have a differential impact on women, who in many societies take principal responsibility for children. Women’s participation in work outside the home is likely to fall. (My colleagues Minardi, Hares, and Crawfurd have written about other impacts of school closures during an epidemic.)

-Travel restrictions will affect female foreign domestic workers. Of course, they also affect male migrants. The distribution will vary by country. Research by Korkoya and Wreh (2015) found that 70 percent of small-scale traders in Liberia are women, so domestic travel restrictions during the Ebola outbreak disproportionately affected women.

-Health resources normally dedicated to reproductive health go towards emergency response. During the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, for example, the “decrease in utilization of life-saving health services translates to 3600 additional maternal, neonatal and stillbirth deaths in the year 2014-15 under the most conservative scenario” (Sochas, Channon, and Nam 2017). In my own research (with Goldstein and Popova), we found that the disproportionate loss of health workers in areas that had few to begin with would likely lead to higher maternal mortality for years to come.

-When women have less decision-making power than men, either in households or in government, then women’s needs during an epidemic are less likely to be met.

Here are four additional concerns:

-Sexual health: During the school closures of Sierra Leone’s Ebola outbreak, “a reported increase in adolescent pregnancies during the outbreak has been attributed largely to the closure of schools.” (UNDP 2015). Bandiera and others find that in villages highly disrupted by Ebola, girls were “10.7 percentage points more likely to be become pregnant, with most of these pregnancies occurring out of wedlock.” A United Nations report gives an even higher estimate of 65 percent. The absorption of health resources by emergency response may also lead to disruptions in access to reproductive health services.

Many girls didn’t return to schools once they reopened, and there were increases in unwanted sex and transactional sex. (Notably, Bandiera and others also find that girls in villages where there were established “girls’ clubs”—safe spaces for teenage and young adult girls to gather and get job and life skills—before the epidemic experienced fewer of these adverse effects.)

-Intimate partner violence rises in the wake of emergencies: Parkinson and Clare document a 53 percent rise in the wake of an earthquake in New Zealand and nearly a doubling in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in the United States. Mobarak and Ramos find that in Bangladesh, increased seasonal migration reduces intimate partner violence, at least in part because women spend less time with the potential perpetrators of that violence. Travel restrictions may be expected to have the opposite effect.

-The burden of care usually falls on women—not just for children in the face of school closures, but also for extended family members. As family members fall ill, women are more likely to provide care for them (as documented during an Ebola outbreak in Liberia, with AIDS patients in Uganda, and in many other places), putting themselves at higher risk of exposure as well as sacrificing their time. Women are also more likely to be burdened with household tasks, which increase with more people staying at home during a quarantine.

-As Mead Over and I have discussed, health crises can trigger economic crises. Economic crises affect women disproportionately, particularly in low-income countries. Sabarwal and others found that men’s labor force participation remained largely unchanged during economic crises, whereas women’s labor force participation rose in the poorest households and fell in richer households.

-Last week, the World Health Organization declared that “this is the first pandemic caused by a coronavirus.” There have been more than 168,000 confirmed cases and more than 6,600 deaths in 148 countries as of publication of this blog. The impact of this pandemic will be felt for years to come. As women are often disproportionately affected by the follow-on effects of the disease, we have to make sure that we keep women’s rights and needs front and center in our responses. A first step in doing that is making sure that women are a central part of the teams designing those responses.

Contributed by David Evans, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development, working on education, health, and social safety nets.

This post benefitted from comments provided by Susannah Hares, Megan O’Donnell, Emily Christensen Rand, and Rachel Silverman.

Original blog published on Center for Global Development website March 16, 2020, see here for the original posting

Reposted with permission from David Evans, senior fellow at the Center for Global Development

- Published in COVID 19, Healthcare

The Homemade Value-Added Stabilizer

“Shelter in place” mandates in the early stages of the U.S. Covid-19 pandemic required many people to stay home, cook their own meals, school their own children, and entertain themselves. Unpaid work served not only as a social safety net, but also as an automatic stabilizer. While it didn’t dampen fluctuations in official Gross Domestic Product, as did unemployment insurance, it clearly helped stabilize consumption.

Just imagine what would have happened if most people had not had refrigerators, stoves, and computers—or just read reports of the plight of homeless people.

By mid-March 2020, many states and localities shut down restaurants for any services other than take-out. Home-produced meals increased of necessity. Many such meals probably consisted of convenient processed foods that could be popped into a microwave oven, but a renaissance of home cooking also became apparent, along with reliance on long-lasting, easily stored items such as rice and beans. Analysis of Google Search terms showed a sharp spike in questions concerning food preparation and storage. As one newspaper put it, America began baking its heart out. Yeast suddenly became as hard to come by as toilet paper.

In 2018, according to the American Time Use Survey, adult civilian women spent an average of .8 hours a day, and their male counterparts .4 hours a day in meal preparation. How much more did they spend in the months of March and April, and what was the monetary value of this unpaid labor, based on what it would have cost them to hire someone to plan, cook, and clean up? How much did they save on eating-out?

Many childcare centers and schools were closed, leaving parents with responsibility for home-schooling, supervising children, and keeping them from going confinement-crazy. The American Time Use Survey averaged the amount of reported time that married mothers and fathers living with children under the age of 18 spent in primary activities of caring for and helping household children over the 2013-2017 period—an average of 2.6 hours per day for mothers not employed and 1.4 hours for fathers not employed.

Under sequestration, both active care and supervisory care (defined as the time in which an adult reported that a child under the age of 13 “in their care” ) ballooned. How much did these two forms of childcare increase? How much did households save on childcare costs?

Video streaming and gaming increased dramatically, especially during afternoon hours, and people began to rely more heavily on streaming for instruction and exercise as well as entertainment. So, while they spent less money (and less travel time) on entertainment away from home, they substituted forms of entertainment that were probably less expensive, on average. How much less expensive?

Between March and May, average household income plummeted as a result of job furloughs and unemployment. The increase in time devoted to household production buffered this loss to some extent—but without answers to the questions above, we can’t know how much. Most recent impromptu household surveys have focused primarily on women’s unpaid work relative to men’s—an important, but different topic.

For years, I have protested economists’ lack of interest in total consumption—defined as the sum of money expenditures and the consumption of home-produced services.

Let me will repeat one example that I have written about in more detail elsewhere: Compare two couples, each with two small children, each earning $50,000 after taxes. Conventional measures treat them as having exactly the same income. Yet one couple may include an adult earning $50,000 and a full-time homemaker/caregiver, while the other includes two adults earning $25,000 each and obviously has less time to devote to unpaid work. If we assigned any positive value to unpaid work, the first household would obviously be better off in terms of both income and consumption.

Market income is just not a very good indicator of total consumption among households with differing inputs of unpaid work. Also, the value of unpaid work is greater in households with more than one person, because of economies of scale in food preparation and childcare. Standard equivalence scales used to adjust household income for household size and composition completely ignore these issues.

Obviously, the additional unpaid work performed while sheltering in place was a source of great stress, especially for those simultaneously telecommuting, zooming, or otherwise trying to fulfill paid employment responsibilities at home. Yet, it’s hard to deny that this work also “added value,” enabling an important form of social provisioning.

The worst-case scenario for a household with children was almost certainly one in which all adults (e.g. mother and father) were essential workers, required to keep working (often at risk to their health) but unable to work from home. Federal and state agencies tried to provide “resources” for these workers, but no guarantees were forthcoming.

In many cases, one of the adults (probably the mother) was forced to quit or take a leave of absence from paid employment. While new federal legislation gives states flexibility to pay benefits where an individual leaves employment to care for a family member, not all states do so.

Such a policy is effectively a paid family leave—something that most states have shied away from for years, making this country an international outlier. The complexity of the new legislation, plus the difficulty of actually filing for and receiving unemployment benefits, has probably kept take-up pretty low even in states that allow this option.

Just one more reason to consider policies such as federal paid family and sick leaves and a universal basic income that could help the stabilizers known as households do their job.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on May 19th, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in COVID 19, Time Use Survey, U.S., Unpaid Work

“Being at Home” is Not Free – Making Informal Care Provision Visible and Providing Support During the Pandemic

The Japanese Government responded to the COVID 19 crisis by declaring a state of emergency and announcing an economic stimulus of 108 trillion yen, 6 trillion of which is allocated to households and small to midsized businesses. However, care work is not mentioned in this state of emergency. In the face of this pandemic, the government should be taking into account the increased burden of home care that is brought on in addition to the concerns regarding the collapse of medical care.

Although medical care is very important, home goes beyond medical care in terms of responsibilities. Take, for instance, an elderly person that has home aid providing essential forms of care – preparing meals, etc. These care workers are taking on huge risks and burdens, and the fact that neither policymakers nor the press are paying attention to this is problematic.

Additionally, as hospitals are overrun with the sickest patients, many those that have contracted COVID-19 are forced to stay home, leaving relatives, especially women, to care for them without the proper PPE or the vigorous sanitation needed. This will result in further spread of the virus, and each household will take on a similar pattern to what has been seen on cruise ships. Furthermore, in Japan, many people live in small homes, making it impossible to create “quarantined zones” within the home. There is also the consideration that many of those in isolation do not have a member of the household to do the shopping. Those individuals are left without access to basic provisions and this is especially the case amongst those that live alone.

Although Prime Minister Abe has thanked the medical staff and truck drivers, he has failed to mention the family care members and the important role they play, which might indicate that family care is seen as a mere obligation, as plentiful as water or air.

The government in South Korea has taken on a much different approach, taking note of these needs, it responded by providing provisions to those that are isolated at home and are unable to go shopping. These provisions show that publicly fulfilling care needs may help in preventing the spread of the disease.

Japan technically has similar measure in place under the Japanese Infectious Disease Control Law, which requires that the government must provide necessities in order to enable individuals to stay home to prevent the spread of infection. However, in actuality, this has not been the case. In Osaka, a modern welfare policy exists to provide coupons for residents for food delivery from local restaurants, helping both those in isolation and local small businesses. This is an example that could be replicated on a national scale with the cooperation of the government and private sector.

I created a survey with colleague Mr. Nanami Suziki to investigate the ease in which people can self-isolate. The survey was distributed through the internet in April 8th and as of April 12th , 330 responses were recorded. These results indicate that domestic work within the home is on the rise, with increasing burdens for those responsible for these tasks within the home. Furthermore, the increased domestic workload is putting strain on those who are remotely working from home.

Survey results show that although in many cases both men and women work remotely, women more often end up taking on all additional home responsibilities imposed by the pandemic, including homeschooling for the children.

As a result, many women are taking leave from their jobs, are working longer hours, and are becoming sleep deprived. Additionally, the increased family stress can lead to domestic violence. Policymakers and the press need to be more attentive to these increased burdens.

Steps can be taken to alleviate this situation, beginning with making care work visible and providing compensation. Further, ensuring employment and income those providing care for individuals in quarantine. This would follow the example set by South Korea in which those that cannot be paid to take leave can apply for living expenses to be supported through the government. As it stands now, Japanese relief policies fail to recognize the increased care burden being faced in the home, primarily by women.

Further, the government should respond by distributing lunch boxes to children that are not able to attend school due to closures, helping those children living in poor households that rely on school lunch. It is also important to support to the continuation of programs that are providing this sort of social care.

There have been some positive results from this situation, such as more family time and communication. Economy is only one aspect of life and moving forward, care work should be made visible in order to create a shift in society that mainstreams the value of “life” over “economy.”

* Thanks to Asahi Okamoto, Kaori Yamamoto, and Yoon Sodam.

This blog is authored by Emiko Ochiai who is a Professor of Sociology at Kyoto University.

Originally published in Japanese to the Women’s Action Network on Monday, April 13, 2020

- Published in COVID 19, Japan, Policy, South Korea

A Time for Reflection on Care

The world outside my study is churning and whirling… as it is engulfed with the fast-evolving health situations in communities around the globe. There are many unknowns about the

COVID-19 illness that has spread rapidly in every continent and the presence of uncertainty—big time—has rattled governments, shaken markets, and upended our daily routines, to say the least.

While I join the hundreds of millions of people who constantly check the news online and in newspapers, radio and/or tv, I also take time to pause. These moments allow me to reflect on

what this difficult time that we are all experiencing means and what it says about us—as

individuals, as members of communities, and as citizens of the world.

For one, I find that:

- each individual action has multitudes of rippling effects, large and small, on others;

- the real world oscillates between predictability and unpredictability; it requires each of us to constantly assess the balance between taking caution and taking risk;

- the distinction between self-interest and altruism (promoting others’ interests) becomes more blurred given the pervasive interconnectedness of our lives;

- adaptation and flexibility are vital life skills that we need to have not just now but at all times;

- we have the ability to change as we obtain more information and as conditions around us change; the notion of fixed tastes and preferences is outmoded;

- the skills that we must hone and develop should prepare us not only to live in a competitive world but also to be able to work together, coordinate and cooperate with one another; for the greater good requires collective action.

As the impacts of the COVID-19 spread intensify, there is growing recognition among governments and the public that traditional efforts for dealing with shocks and managing risks through conventional emergency responses are inadequate. Strategic thinking is needed as much as the ability to respond quickly and to take proactive measures. There is an urgent need to build the adaptive capacity and longer-term resilience of communities and societies.

One striking fact about the current global pandemic is its tremendous effect on the care sector. This includes not only the health care systems employing doctors, nurses, aides, and other health professionals but also the unpaid care labor provided by family members, neighbors, and kin.

Many are changing their daily life patterns to provide further assistance and care support for those who are vulnerable such as their parents or grandparents and for those who are self-quarantined. Many more are willing to take the risk of exposure to care for those who have tested positive and are ill but are staying at home because the healthcare system is inadequate, inaccessible, and/or overwhelmed. The shutdown of schools and daycare centers further adds demand for unpaid care. Parents are struggling to care for their children while at the same time trying to tele-work from home.

“How can I write or have meetings with my six-year old around?”

The cloak or mantle that hides the emerging crisis of social reproduction, or the under- provision of care for people who depend on it, is removed. This global pandemic exposes the heavy demand on those who carry the responsibility for providing care for the sick, the young and the frail elderly, the vast majority of whom have been women. It has upended preconceived notions such as: each individual is a ‘Robinson Crusoe’ in families that can find their own solutions to provide care, and that one’s ability to pay should determine who accesses care in the private sector.

The Care Work and the Economy Project joins the efforts of other organizations, research institutions and advocacy groups towards making the care sector visible to policymakers. The heavy care burden that is now being shouldered by health care systems, households, communities and countries throughout the world makes it imperative to bring care work out of statistical shadows and to remove the veil of ignorance in economic policymaking.

Let us hope that this time is truly different and that the jolt brought about by the current pandemic leads to more openness in the academic community and among policymakers towards a paradigm shift and policy change.

March 2020

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, elderly care, Maria Floro, Policy