Current Situation of Care Work in South Korea: 2018 Family Survey

The Care Work and the Economy project’s 2018 fieldwork in South Korea helped us learn a great deal about how childcare and eldercare is provisioned, both in the paid and unpaid care sectors, in Korea.

The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys, including two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers and unpaid care providers. The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and recipients.

What We Learned about Family Caregiving in Korea

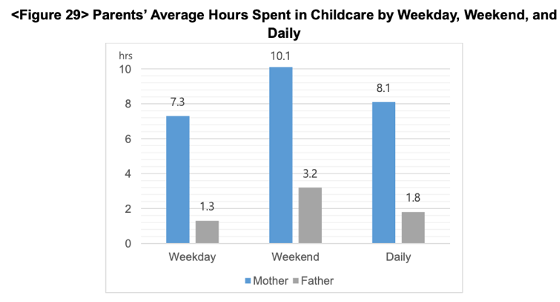

Although many families use at least one external care service to assist with childcare, 22% of respondents reported that their childcare was done only by family members (Kang et al.). Mothers spent six to seven hours more than fathers taking care of children on average.

(Kang et al.)

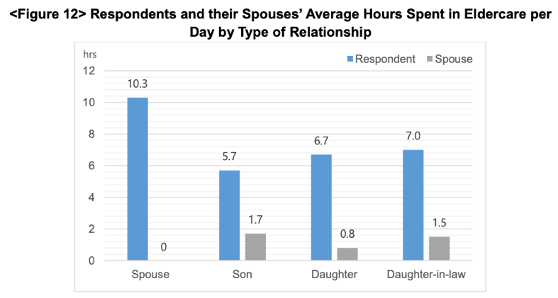

In contrast, 67% of respondents reported that their eldercare was done by family members; the rest reported using external care – usually the national LTC program. The primary caregivers were daughters-in-law (37% of the time), daughters (35%), spouses (15.6%), and sons (11%) (Kang et al.). Figure 12 shows how rather than the elder’s biological children, daughters-in-law provided the most care in terms of time, excepting the elder’s spouse.

(Kang et al.)

The cost of eldercare is shouldered solely by the primary caregiver in many cases (Kang et al., 2021)

Only 20% of family eldercare providers reported receiving regular financial support from other family members, less than 30% reported receiving help on an irregular basis, and only 8% of those over 65 years old were currently receiving LTC insurance program benefits.

Unpaid care provisioning impacts women’s employment.

The surveys showed that “families in which mothers were the sole caregiver for the child had the highest proportion of unemployed mothers, whereas families that received help with childcare from grandparents or paid care service had the highest proportion of employed mothers. With respect to both types of care arrangements, it was mostly daughters and daughters-in-law serving as primary caregiver, almost 70% of whom were unemployed.” (Kang et al.).

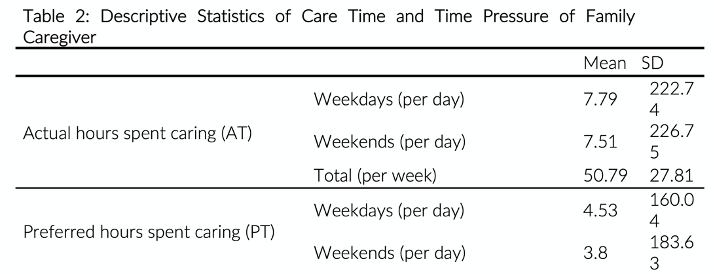

When asked about their preferred hours spent caring, eldercare workers reported a considerably lower number of hours on average than the actual hours they spent caring (see Table 2).

(Cha and Moon,2020)

Studies in the CWE-GAM Project stress concerns about the “quality of the caregiver’s life and the care they provide as well as the quality of life of the care recipient. Especially given that women are typically taking on the role of caregiver, this issue cannot be detached from concerns regarding women’s labor, women’s quality of life, and gender equality in Korea.”

Current Situation in Korea – Government Implications:

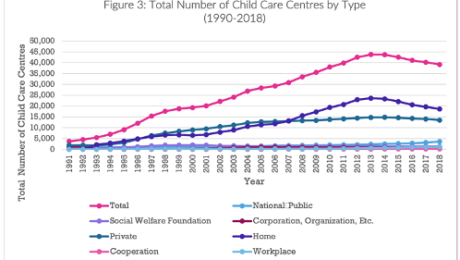

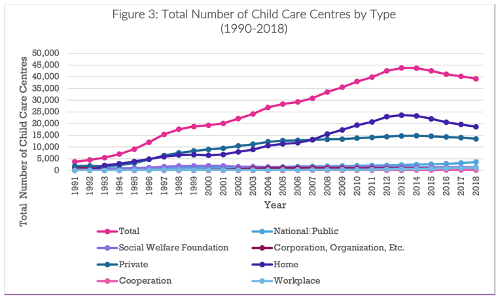

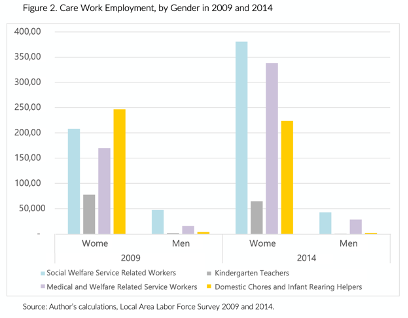

Korea currently “ranks amongst the top 10 OECD countries in terms of public investment in childcare and education” and implemented a mandatory universal LTCI program in 2008 (Peng et al 2021). Figure 2 and 3 show the evolution of child care and care work over time.

(Peng et al. 2021)

(Suh 2020)

Studies report that despite the social care expansion, “childcare and long-term care sectors are heavily dominated by women, and these care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and precariously employed. Care work is also accorded low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress” (Peng et al. 2021; Suh 2020).

Suh (2020) finds that “public investment in quality care services tends to improve the working conditions of care workers (thereby benefiting care recipients), and unregulated private provision tends to worsen them.”

This suggests that “the government and public sector should drive the effort to meet the multi-faceted challenges posed by the growing demand for care work” (Suh 2020).

“The Korean government […] continues to see care work as an extension of women’s unpaid care work and social care expenditure as something that need to be tightly controlled. A better understanding on the part of policymakers about the importance of care and the role of care work and the care economy in generating employment and positive economic growth and supporting a healthy productive economy is therefore necessary.” (Peng et al.)

This blog was contributed by Aina Krupinski Puig, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha, Seung-Eun, and Hyuna Moon. (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family

Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eunhye, Ki-Soo Eun, Jiweon Jun, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “Care

Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

Peng, Ito, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “An Overview of Care Policies and the

Status of Care Workers in South Korea.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/EHN0-R646.

Suh, Joo Yeoun. (2020). “Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea.” Care Work and the

Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/bpdf-v686.

- Published in Child Care, Elder Care, Paid Care Services, Policy, South Korea, Unpaid Care Work

Making Care Count

The COVID-19 pandemic has informed our understanding of the care economy, exposing disproportionate inequities that must be addressed to alleviate the international erasure of care workers. These issues are addressed in the latest Susan and Michael J. Angelides Lecture, in which Naomi Klein moderates a discussion between Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal and CWE-GAM researcher Dr. İpek İlkkaracan on COVID-19 and the care economy.

We live in an economic system that has traditionally deprioritized and invisibilized care workers, many of which are women of color, migrant, and poor women. The economic crisis brought on by the pandemic has consequently given policymakers and academics “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address [the valuation of care work] from an intersectional [approach],” states Congresswoman Jayapal.

The Care Crisis Exposed by the Pandemic Recession:

When mass unemployment hit during the pandemic, the cracks in the economic infrastructure of America began to show. As millions of people lost their jobs, the highest increase in the number of uninsured Americans was subsequently recorded. This high number of uninsured people is a direct consequence of healthcare being employer-sponsored. Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “Medicare For All would have strengthened the response to the pandemic…30 percent of COVID-19 deaths were related to a lack of insurance.”

While gains were made in the past decade in regards to gender equality in the workplace, Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “as soon as the pandemic hit, it was the women who went back to taking care of [their] families.” Dr. İpek İlkkaracan explains that this is because “the nature of women’s employment is often determined by their care responsibilities…unpaid care work is often articulated as one of the most significant barriers to labor force participation.” This notion was reflected in jobs reports—in December of 2020, women accounted for 100 percent of job loss, and within that, 154,000 Black women exited the workforce.

In its current state, the care economy produces a pattern of inequality that disproportionately affects women of color and migrant women. The average caregiver salary is $12.74, and the care work sector is marked by poor working conditions with no adequate social protections and low wages. This is why, as Congresswoman Jayapal notes, the fight for one fair wage is pertinent. “An increase in the minimum wage would give 32 million workers a raise, 60 percent of which are women while 1 in 4 of the women who would benefit from this increase are Black or Latina.”

A Framework for a More Caring Economy:

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan has developed a framework that acknowledges the care economy. This framework, coined as the Purple Economy (a nod to the color representative of many women’s movements), envisions a gender-egalitarian and caring economic system. Dr. İlkkaracan recommends “labor market regulations and investment in care services such as long-term care, early childhood education, education, and healthcare” as policy interventions to start the process of adequately valuing care.

Not only is investment in care important from a humanitarian and ethical perspective, but it is also conducive to economic stability. Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has revealed that investment in care services produces a high employment multiplier: for every dollar invested in care, three times as many jobs are created in the wider economy. This is because the care sector is intertwined with other sectors such as food, transport, and financial services. In the Asia-Pacific region, Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has shown that “up to four trillion dollars could be added to GDP if unpaid care work (75% of which done by women) was valued in market terms.” While this may seem astronomical, the amount of unpaid work completed globally in one day equates to 16.4 billion hours—which translates to two billion full-time jobs. Dr. İlkkaracan’s recent research also reveals that a “3.5-4% commitment of GDP to investment in care services would create 120 million additional jobs and have a large impact on poverty alleviation.”

To watch the full conversation and learn more about the Purple Economy, see below.

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan is a CWE-GAM researcher a part of the Rethinking Macroeconomics and Gender Aware Applied Economics Working Groups.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Gender-Equal Economy, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, U.S.

Biden’s American Jobs Plan Could Be Monumental for the Care Economy in the U.S.

Last month, the Biden administration revealed the details of the $2 trillion American Jobs Plan.

The plan recognizes that investing in the care economy, as with investments in traditional infrastructure, can lift incomes, unleash productivity, and pave the path towards a more equitable economic recovery and growth.

Addressing the care crisis

Built into the plan is a pledge to “solidify the infrastructure of our care economy by creating jobs and raising wages and benefits for essential home care workers.” The plan calls for Congress to invest $400 billion towards expanding access to quality, affordable home- or community-based care for aging relatives and people with disabilities. These investments will help Americans to obtain the long-term services and support they need, while creating new jobs and offering care workers a long-overdue raise, stronger benefits, and an opportunity to organize or join a union and collectively bargain. Research has shown that increasing the pay of care workers leads to better quality care overall. Through creating well-paying care jobs with benefits and o collectively bargaining rights, as well as building state infrastructure, the plan aims to improve both the quality of job for care workers and the quality of service for care recipients.

Lack of access to childcare makes it harder for parents, especially mothers, to fully participate in the workforce, hurting families and hindering U.S. growth and competitiveness. In areas with the greatest shortage of child care slots, women’s labor force participation is about three percentage points less than in areas with a high capacity of child care slots. The pandemic has severely exacerbated this problem with more than 1 in 4 facilities still remaining closed as of December 2020. President Biden is calling on Congress to provide $25 billion to help upgrade child care facilities and increase the supply of child care in areas that need it most. These funds are to be provided through a Child Care Growth and Innovation Fund for states to build a supply of infant and toddler care in high-need areas. Also included in this $25 billion is a call for expanded tax credits to incentivize businesses to provide care facilities at their establishments. This will grant accessible, high quality care and learning environments for children of employees. This particular part of the plan is structured so that employers will receive 50 percent of the first $1 million of construction costs per facility.

Investment in care is investment in infrastructure

As Cecelia Rouse, Chair of the Economic Advisors for the Biden administration, recently indicated during a recent press conference, we need to “upgrade our definition of infrastructure” to include the care economy. Rouse defended the Biden administration’s plan to spend $400 billion of the infrastructure plan’s budget on the care economy, defining it as a legitimate infrastructure investment and a key component to addressing economic inequities in the U.S. The care economy is critical to U.S. economic activity, and its absence would greatly hinder economic productivity. The inclusion of care work and the care economy in the American Jobs Plan is a critical first step in mending a critically broken care infrastructure in the U.S.

Still, it is only the first step. The U.S. is the only industrialized nation that fails to provide national paid family leave and medical leave programs, and where hundreds of thousand sit on waiting lists for desperately needed home care. LeadingAge, which represents service providers in the sector, estimates that half of all Americans will need long-term services and support after turning 65, and that by 2040, a quarter of the U.S. population will be 65 or older. In addition to the President’s proposal for the care economy, we also need investments to finally put America on a path to universal childcare and early learning, national paid family and medical leave and paid sick days for all workers. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed both the importance of care work and the vulnerabilities of our care infrastructure. At the same time, it has also created an opportunity for us to rethink the value of care and care work, opening ways for us to rebuild a more resilient care infrastructure and a more inclusive economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Economic Recovery, Policy, U.S.

Women and the Pandemic in the U.S.

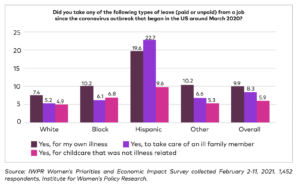

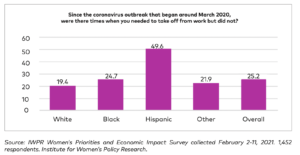

Institute for Women’s Policy Research released a report in February 2021”IWPR Women’s Priorities and Economic Impact Survey” outlining a recent poll of 1452 women in the U.S. The findings are backdropped by the experience of women throughout the pandemic and resulting economic turndown, in which 2.35 million women have left the workforce since February 2020.

Some of the key findings from this survey are:

- 1 in 4 women report that they are worse off financially than one year ago

- Nearly half of all women are worried about the financial situation of their families

- 1 in 4 women report having needed to take time work off but did not do so

- 40% of women reported care demands stopped them from working or forced them to reduce hours

- 69% of women support paid sick time to have a child, recover from a serious health condition, or care for a family member

- 20% of women with children want the Biden administration to address childcare and education in the first 100 days

In terms of women experiencing reduced paid work as a result care demands, this has also been pointed to within recent working papers put out by the

The impact of care demands on women’s paid work is explored in a number of Care Work and the Economy Working Paper Series. For instance in two recent papers, “Gender Wage Equality and Investments in Care: Modeling Equity and Production” and “Parental Caregiving and Household Dynamics”.

Education and childcare were listed among the top priorities for the Biden administration to address within the first 100 days among survey participants. This is largely because women’s ability to reenter the workforce largely depends upon safe reopening of schools and childcare facilities.

Latinas have been hit particularly hard according to this survey, reporting the highest levels of taking leave from jobs in order to provide care. However, across all ethnicities, 69 percent of women expressed strong support for paid sick leave and the ability to take time away from work to provide care or recover from illness.

The Unites States remains the only high-income country in in the world that fails to provide guaranteed paid sick or family leave for workers. The Family Medical Leave Act, which provides unpaid job protection, and only for about 56 percent of workers. The Families First Coronavirus Relief Act has provided access to paid leave as a result of the pandemic but falls short in the fact that more than 100 million workers are excluded from this because they are caregivers.

In order to address the many issues identified throughout this survey, there is strong need for targeted programs and policy solutions that will aid a gender equitable recovery. This recovery should not only address immediate short term needs but include long term strategies that will create more resilient systems that recognize the contributions of women to the workforce, society and family structure.

IWRP specific recommendations for the short term are:

- Continuing economic impact payments

- Expanding access to affordable healthcare

- Providing paid sick and medical leave

- Raising the federal minimum wage

- Building a new childcare infrastructure

Equitable economic recovery necessitates a national care system that meets the needs of all families, raises wages and provides quality childcare, treating it as a public good instead of a private obligation.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Policy, Policy Briefs & Reports, U.S.

Hawai’i and Canada Provide Lessons for Feminist Economic Recovery from COVID-19

The need for an inclusive, gender-equitable recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is slowly gaining recognition as it lays bare and exacerbates inequities in economic, social, health, and environmental policies and programs.

The Hawai’i State Commission on the Status of Women convened a working group to develop and share principles and practices for implementing a gender-responsive and feminist response to COVID-19, culminating in the publication of Building Bridges, Not Walking on Backs: A Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for COVID-19.

Similarly, the YWCA Canada and the Institute for Gender and the Economy (GATE) at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management published a joint assessment, A Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for Canada: Making the Economy Work for Everyone. The plan highlights critical principles and provides actionable recommendations for the government to develop and implement post-pandemic recovery policies that are equitable and inclusive of all marginalized people.

Together, the Canadian and Hawaiian plans provide a roadmap to recovery through gender-transformative policy-making. Both are built on an intersectional analysis of the impact of the pandemic and call for an approach to economic recovery that examines and confronts the root causes of inequality, including but not limited to patriarchy, ableism, queerphobia, white supremacy, colonialism, classicism, and racism.

A recent brief by Alexandra Solomon, Kate Hawkins, Rosemary Morgan of the Gender and COVID-19 Working Group describes the intersecting, complementary, and mutually reinforcing elements of the two frameworks and echoes the call for feminist economic recovery. It provides a collection of best practices for the core tenets of post-pandemic policy-making which should be echoed and adapted by policy-makers from other settings.

Key Recommendations to Policymakers:

- Pandemic responses should be underpinned by data that is disaggregated by sex and other markets of inequity at the national and subnational level. This data should be made public and used in decision making.

- Women-led organizations, feminist academics and women’s experiences and ideas should be at the center of recovery efforts in government bodies, official consultations and online spaces.

- The provision of universally accessible, free childcare and long-term eldercare should be central to economic recovery plans and attempts to ‘open up’ the economy. Precariously employed immigrant care workers should be provided with an expedited path to permanent resident status.

- Austerity-induced budget cuts should be avoided as they impact most greatly on the poor, women and other marginalized groups. Instead policy-makers should strengthen public welfare assistance (such as unemployment benefit) and labor rights (such as paid sick leave, family leave and a guaranteed living wage).

- Special stimulus funds should be designated for high risk groups, such as those who are not eligible under existing government schemes, are disproportionately experiencing financial hardship and poverty, and already face barriers to accessing their rights to health, safety, independence and education.

- Invest in universal, affordable, and sustainable access to water, sanitation, hygiene and housing, and prioritize closing the gender digital divide.

- Support women in female dominated economic sectors particularly hard hit by the pandemic as well as historically marginalized women workers, such as Indigenous women and sex workers.

- A feminist recovery is aligned with a ‘green’ recovery and the two should be considered in conjunction.

- Revisions of fiscal and monetary policies should be taken as opportunities to address inequality in wages, employment, and quality of life.

- Health systems should be restructured to focus on Universal Health Coverage and to address problems in service access and quality due to sexism, colonialism and white supremacy. Tackling the social determinants of health should be a priority.

- All hate, violence, and oppression against women, gender-diverse people, and Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities must be addressed in the COVID-19 recovery.

READ FULL BREIF:

Solomon, A., Hawkins, K., and Morgan, R. (2020). Hawaii and Canada: Providing lessons for feminist pandemic recovery plans to COVID-19.The Gender and COVID-19 Working Group.

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in COVID 19, Policy, Policy Briefs & Reports

U.S. Needs to Save Child Care Before It’s Too Late

The childcare system in the US was already in a critical state of inadequacy, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made this worse. A recent report released by the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (JEC) – “We Need to Save Child Care Before It’s Too late” – explores the U.S. childcare crisis in detail, outlining the shortages in child care and the consequent economics effects of those shortages.

According to the report, as of August 2020, roughly 214,000 U.S. childcare workers were out of a job and 4 out of 5 childcare providers expected to close permanently if no public assistance is provided. This is of course having a trickle-down effect on the working parents that rely on this childcare, and 13% of parents reported having to reduce their working hours.

This issue is further compounded in the many areas throughout the country considered to be “childcare deserts” where the supply of childcare falls well below the demand and for many families is not accessible due to cost constraints. Although there are assistance programs available for those in need, such as the Head Start program, many of those that qualify still do not receive assistance due to severe lack of funding. In over half of states, childcare and early childhood education exceeds the cost of college tuition, and bearing this burden is extremely difficult for lower income families.

Middle income families that do not qualify at all for government funded programs are under even more strain with the financial obligations of childcare. Infant care is in particular incredibly expensive, and a median income family home could spend anywhere from 23% to 77% of their income on the care of their infant, depending on the state. For single mothers in the median income range, this could be from 29% to 94%.

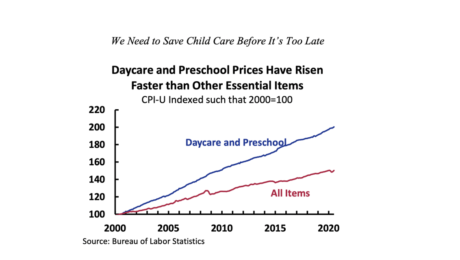

Childcare costs in the U.S. are exponentially higher than its OECD counterparts. The U.S. spends less that half the amount of its GDP on childcare in comparison to the average of other OECD nations. In fact, the U.S. spends 3 to 6 times less than France, New Zealand, and all the Nordic countries. Where in many OECD nations, childcare is free or very inexpensive, making it widely accessible, in the US, the accessibility and quality of childcare for working parents is contingents upon their economic status. A lack of accessible and affordable childcare leads to lost earnings for parents, an estimated $20 – $35 billion in total, according to the Economic Policy Institute. This in turn translates into a loss of roughly $4.2 billion dollars in federal and state tax revenue per year. The cost of childcare is skyrocketing past the rate of inflations as well, between the years 2000 and 2020, day care and preschool costs rose double that of inflation.

Extensive research has shown that accessible and affordable childcare has strong positive economic benefits and contributes to the well-being of children and parents. Without the benefit of accessible and affordable childcare, many parents, mostly women, experience reduced earnings for the duration of their careers. This also contributes tremendously to the gender wage gap. Furthermore, according to a 2015 Council of Economic Advisors report, every dollar spent on childcare and early education carries the potential to yield eight dollars in societal benefit.

Childcare workers also struggle due to low wages, poor benefits, and precarious working conditions. In 2017, an average childcare employer kept 13 workers on payroll, each of whom earned just $20,886 on average in annual compensation. In 2019, the median hourly wage of U.S. childcare workers was $11.65, a near-poverty wage. Nonetheless, employee’s compensation is the highest cost for these establishments, as they must maintain a low ratio of children to caretaker, which varies from state to state. Cost of rent is another major expense for childcare providers, but reducing the size of the facility, and therefore the rent costs, is not a viable option as crowding and lack of outdoor space has been shown to increase the risk of infections and injury within the centers.

There is still a great amount of work to be done in the U.S. The CARES Act passed in March of 2020 provided $3.5 billion of funding to states in childcare subsidies for low income families. Additionally, the inclusion of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) provided $2.3 billion to childcare providers across the country, enabling 460,000 childcare workers to remain employed. Although these measures were helpful, much more assistance is still needed. For the most part, smaller childcare centers and home-based programs were not able to access these PPP funds at all, with only 29% of them receiving these funds. The vast majority of childcare operations across the board, many of which single-person operations, were also not able to access these PPP funds at all. The HEROES Act, passed in the House of Representatives in May, would provide another $7 billion in relief for childcare centers and $850 to fund child and family care for essential workers. However, this legislation has stalled in the Senate.

This pandemic has dealt a devastating blow to an already inadequate childcare system in the U.S. Without desperately needed assistance, the U.S. faces the potential of losing 80% of its childcare capacity. This will in turn deprive working parents of the critical services and infrastructure needed for the economy to recover. Read the complete report “We Need to Save Child Care Before It’s Too Late.”

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Policy, U.S.

LTC Sector Faces a Number of Challenges, Today and Going Forward: An OECD Report

OECD Health Policy Studies has released a 2020 report “Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly.” This report addresses a number of important issues while acknowledging the tremendous impact that COVID 19 has had on elderly people and their caretakers. Across OECD countries, more than one out of every six individuals is above the age of 65, and of those roughly 60% live with multiple chronic conditions, making them even more susceptible to the potentially deadly impacts of the virus. Furthermore, many elderly individuals struggle with sufficient access to social support and lack the ability to properly deal with the mental strain of living in a world being affected by a global pandemic.

Beyond these strains, there is a crisis in workforce shortcomings of the Long Term Care (LTC) Sector, which becomes even more problematic in light of the fact that an estimated 50% of COVID 19 related deaths are occurring in LTC facilities. This OECD report begins by addressing many of these shortfalls within the LTC sector, and policies that have the potential to address them.

Within three-quarters of OECD countries, the aging population has outpaced the workforce within the sector since 2011. This is the case even in the countries that have a higher workforce supply than the OECD average such as Japan and the U.S. Within the sector, women make up 90% of the LTC workforce. Attracting a younger workforce has been particularly difficult, and on top of that maintaining workers over the age of 50 is also a challenge. This is even more concerning given that the median age of LTC workers is currently 45.

Many OECD nations have made moves toward relocating their elderly out of facilities and back into the community. This is provoked by the desire to match the preferences of their elderly populations with home-based care, in addition to containing LTC spending. However, a lack of home-based workers has made this challenging, and LTC institution-based workers remain representative of the sector’s workforce across the OECD. This is in large part due to the fact that these institutions cater to the most disabled, which requires a larger workforce. Furthermore, many community-based solutions are not yet equipped to take in these types of complex cases.

The aging of the postwar “baby boom” generation is a factor that will contribute to the increased need for LTC workforce. This also contributes to the predicted increase in labor shortages in the sector to meet the needs of this population going forward. Further, unpaid informal care workers, like that of family members that would care for this aging population, have seen an increase in their own professional workload burdens. When the workload of professional life and caretaking becomes too great, LTC facilities are a means in which to relieve some of that strain. Additionally, as birth rates decline, families become smaller and more women are pursuing professional endeavors, the availability of informal caregivers for the aging population decreases looking into the future. This contributes to another foreseen LTC workforce shortage in the future.

These shortages call for an increase in recruitment within the LTC sector. As the sector workforce ages, attracting younger workers has proven difficult as they, mostly women, are drawn to sectors that have a more appealing image such as a child or hospital care. Additionally, LTC jobs are still widely considered to be feminine positions, and the sentiment on this subject matter has been slow to change.

Foreign-born workers play a significant role in recruiting and retaining LTC workforce. They are highly over representative within LTC across the OECD when compared to other care sectors, and many of them are young, Often, they tend to come into the sector with high levels of skill sets, even overqualified. Micro-econometric analysis has shown that in the U.S. and the UK, these foreign-born workers have higher retention rates than others within the sector.

In terms of recruitment, drumming up interest in the available positions is also problematic. In some cases, many vacancies receive no applications at all. On top of this, recruiters often have a difficult time identifying qualified candidates out of those that do apply.

In order to address this, many countries have focused on four main policies:

– Target recruitment to the traditional pool

– Improve the Image of the sector

-Recruit outside the traditional pool

-Increase the recruitment of for foreign-born workers

Overall, better policies are needed in order to improve recruitment within the LTC sector, and thus far few OECD nations have implemented policies in order to do so. By addressing these issues addressed within the first section of this report, there is potential for effective improvement.

- Published in elderly care, Long Term Care Sector, Policy

Biden’s Care Plan Has the Potential to Change Care Work in the U.S. for the Better

Joe Biden has officially accepted the Democratic Presidential nomination, and he and his team plan to make substantial investments in the infrastructure of care in the U.S. if he wins in the Presidential election. The potential of this plan to provide much-needed support for care workers, both paid and unpaid, is more important than ever amidst the pandemic.

Even prior to this pandemic, the U.S. has long suffered a caregiving crisis. Family caregiving needs often come with incredible financial, emotional, and professional burdens. Professional caregivers, disproportionately women of color, have long been underpaid and undervalued. The pandemic has exacerbated these issues, leaving parents struggling to find the care services needed while juggling careers. There are a number of measures that have been proposed by the Biden team to address the many issues currently plaguing the overall care system in the U.S. today.

Elderly individuals in nursing homes are feeling an increasing need to be cared for at home rather than in community living situations where they are more vulnerable to COVID-19 exposure. The Biden care plan addresses this by aiming to close the existing Medicaid gap to allow for home and community-based care services while creating a state innovation fund for cost-effective direct care services. This will provide more affordable and accessible care on that front. This step will also help to alleviate the extensive waitlists now existing for those under Medicaid to enter home and community care programs, providing these services for 800,000 individuals. If implemented properly, this initiative allows the opportunity to provide more functional care systems that grant greater independence to elderly individuals, while also freeing many unpaid care workers, such as family members, to pursue professional endeavors.

This plan also proposes increasing wages and benefits for caregivers and early childhood educators while providing opportunities for training, professional growth, and unions. This particular initiative takes into consideration the fact that early childhood development is incredibly important, and quality childcare is essential for children to grow into healthy, productive members of society. Universal preschool will also be provided via tax credits and sliding scale programs. Furthermore, included is an investment into safe and developmentally appropriate childcare facilities, including bonus pay for those providers that operate non-traditional hours, such as early mornings, late evening, and weekends. By increasing access to childcare centers with more flexible hours, the burden for many families will be lifted; currently, many parents that don’t work traditional Monday through Friday hours are left scrambling to find adequate care. These initiatives overall will have significant positive impacts on working parents, particularly women. Far too often, women find themselves sacrificing professional progression and development due to the constraint of inadequate or unaffordable childcare.

For those parents who grapple with the decision to further their education as a result of unaffordable and reliable care, investment in childcare centers at community colleges is also included in this plan.

Lastly, expanding the awareness of the Department of Defense fee assistance childcare programs so that all military spouses have the ability to pursue their professional development and education.

In order to pay for these initiatives, the Biden team has estimated a cost of $775 billion over the span of ten years, to be funded by rolling back certain tax breaks for those earning over $400,000 annually. A $5000 tax credit or Social Security credits for those providing unpaid care for members of their family is also proposed. Further, the plan seeks to offer low- and middle-class families up to $8000 in tax credits to assist in paying for childcare. For those that choose not to claim this credit, high-quality care is to be provided on a sliding scale, where it is estimated that families will not pay over $45 per week.

Although this plan is incredibly ambitious, and its implementation is not a guarantee, it sets a precedent that has been long lacking within the U.S. care work sphere. Implementation of these initiatives on any scale would prove beneficial to both the paid and unpaid care economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy, U.S.

Digital Forum on Reopening Long Island and Building a Fair Economy:Care Work in the COVID Crisis

Earlier this month, the Hofstra Labor Studies and the Center for the Study of Labor and Democracy in collaboration with Long Island Jobs with Justice and A.L.L.O.W. (Advancing Local Leadership Opportunities for Women) conducted a virtual forum addressing care work in the context of COVID-19. This discussion emphasized the financial and mental health challenges associated with all types of care work during this pandemic, and the immense need to address and resolve these issues in order to assist with a fair and sustainable economic recovery. Although the discussion is focused primarily on Long Island and New York, the problems indicated are applicable to care work throughout the U.S.

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest that the unemployment or the stress of juggling work and home life as a result of the crisis has hit women much harder than men. This discussion utilized academia as an example of this, drawing upon data indicating that academic journal submissions have greatly increased among men since the beginning of the pandemic, but sharply decreased among women. For those working in academia, publishing work is crucial to professional advancement.

The pandemic has also shed a harsh light on the fragility of the overall childcare system in the U.S. Many families lacked adequate childcare even before the pandemic, forcing them to rely on unpaid care work. These existing issues paired with the recent closures of childcare facilities has exacerbated the problem.

Although the CARES Act did include childcare support, New York receiving $164 million going toward the childcare industry to provide protective equipment and cleaning supplies, the panel argues that while helpful those measures still did not provide adequate relief. The HEROES Act could potentially provide further relief for the care industry, but participants of this forum are less than optimistic about it providing the level relief needed.

The International Labor Organization estimates that three-quarters of unpaid care worldwide is provided by women. In the U.S. women provide 37% more unpaid care work than men on a daily basis. Among care providers in the U.S., Hispanic women do the majority of unpaid care and account for the biggest gap among men and women. Beyond traditional gender roles, this is largely tied to economics; oftentimes men have opportunities to make more money. But generally speaking, even when both parents work full time, women are still taking on more unpaid work even if they are earning more money than the male figure within the household.

There is also a societal tendency which expects care workers to be exceptionally giving. This is highlighted in the fact that even within paid care work positions, there is a fair amount of unpaid work being performed. For example, staying with an elderly person at their doctor’s appointment a couple of hours after the official workday has ended. This is a constant strain within the care industry, and COVID-19 has increased the pressure on this component of unpaid work within the paid care industry.

Additionally, the many racial and ethnic disparities within care work serve as a microcosm of larger racial inequities prevalent in society. For example, in New York, 80% of care workers are women, and a large majority of them are women of color. Furthermore, care workers in New York typically make minimum wage yet are still known to go above and beyond in their roles to ensure the best care is provided, regardless of whether or not it is part of their job description. This existing issue has been pushed to a new level due to COVID-19; now many of our care workers are putting their lives on the line.

Part of the reason that low wages are prevalent within the care sector is the historical association that care work is a “women’s job,” coming naturally and requiring little skillset. This sentiment in the U.S. is compounded by care work being viewed as the responsibility of the individual. The decision to have a family is viewed as a personal choice, therefore the basic needs of childcare are the sole responsibility of the parents, not something to be addressed via larger social safety nets.

New York is facing a particularly troubling dilemma within its care work industry. Despite the fact that a large majority of the workforce is comprised of immigrants, the guidelines that have been released outlining protection measures from COVID-19 are only available in English. This is concerning given that some workers may not yet possess the English language proficiency necessary to fully comprehend these guidelines.

In order to address these strains within the care work industry, political will and national policy are needed. The U.S. Department of Defense provides an exemplary model that could be emulated on a national scale. This government sector presently has one of the best childcare systems available in the U.S., operating on a sliding scale making it accessible to all those within the department that need it. This allows these federal employees to perform their duties with the comfort of this social safety net.

Furthermore, at the local level, immediate state, and county-level funding for care work can have a significant impact on the accessibility needed during this stressful time. Without swift action on the policy level, the issues discussed will continue and have detrimental effects on not only families, but economic recovery as well.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in COVID 19, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy, U.S.

The True Cost of Caregiving: An Aspen Institute Digital Discussion

Even in a typical year, U.S. households are estimated to experience $31.9 billion in lost wages as a result of inadequate childcare and paid leave. Roughly 1 in 5 people living in the U.S. today incur caregiving expenses, and the need for care work is experienced in nearly every household at least once. Those who are professional care workers, disproportionately women of color, are underpaid and therefore susceptible to financial insecurity. Those insecurities have been exacerbated even further amidst COVID-19 and the resulting economic downturn.

In June 2020, the Aspen Institute Business and Society Program hosted a digital discussion “Paid Leave, Livable Wage, Affordable Care: Policies that Could Avert the Next Crisis” in conjunction a policy brief “The True Cost of Caregiving” that was released in May. Within this discussion, the panel focused on the fragility of the care system and the financial stability of those providing care, both paid and unpaid. The panel not only addresses these issues but seeks to re-imagine a system in which care is treated like a public good, examines the hierarchy of human value, delves into the historical context behind care work in the U.S., the vulnerability of care workers in the current pandemic, and the inefficiency of the current care economy within the larger economic system.

A number of important questioned are addressed such as:

– How to quantify the benefits of paid leave, livable wages, and affordable care policies?

-What are feasible policy responses to COVID-19, in both the short term and long term, that can lead to better systems of caregiving in the U.S?

-What does an inclusive and equitable care system could look like?

-Who bears responsibility for building this system?

Further, this panel brings to the table the idea that care work should be invested in collectively as a nation, as opposed to being looked at as an individual burden; which puts increasing downward pressure on those who are already disadvantaged in the U.S. due to race and gender.

Policies that address these concerns could assist in not only building a more equitable system of care but have the potential to aid in averting future crises like that which the care economy finds itself in today.

- Published in Child Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Policy, U.S.