COVID, the Old and Canada-What’s Wrong With Us? A Massey Dialogues Discussion

A recent virtual presentation from Massey College, “The Massey Dialogues: COVID, the old and Canada – What’s wrong with us?” brought together a panel to discuss how the detrimental impacts of COVID-19 in Ontario and Quebec fall alarmingly onto the elderly population. In fact, 80 per cent of pandemic deaths in Canada have occurred among the institutionalized elderly, the highest proportion in the world.

Ito Peng joins this conversation as a special guest to discuss the pandemic and its impact on Canada’s Long Term Care (LTC) sector, and ways through which the dominant thinking around market value/productivity neglects to value the work that older adults have already contributed to the economy throughout their lives, and fails to recognize their role as keepers of history and caretakers themselves.

In this discussion, Ito Peng is joined by Massey Fellows Dorothy Pringle, Husayn Marani and Michael Valpy.

- Published in COVID 19, elderly care, Expert Dialogues & Forums

U.S. Needs to Save Child Care Before It’s Too Late

The childcare system in the US was already in a critical state of inadequacy, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made this worse. A recent report released by the U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee (JEC) – “We Need to Save Child Care Before It’s Too late” – explores the U.S. childcare crisis in detail, outlining the shortages in child care and the consequent economics effects of those shortages.

According to the report, as of August 2020, roughly 214,000 U.S. childcare workers were out of a job and 4 out of 5 childcare providers expected to close permanently if no public assistance is provided. This is of course having a trickle-down effect on the working parents that rely on this childcare, and 13% of parents reported having to reduce their working hours.

This issue is further compounded in the many areas throughout the country considered to be “childcare deserts” where the supply of childcare falls well below the demand and for many families is not accessible due to cost constraints. Although there are assistance programs available for those in need, such as the Head Start program, many of those that qualify still do not receive assistance due to severe lack of funding. In over half of states, childcare and early childhood education exceeds the cost of college tuition, and bearing this burden is extremely difficult for lower income families.

Middle income families that do not qualify at all for government funded programs are under even more strain with the financial obligations of childcare. Infant care is in particular incredibly expensive, and a median income family home could spend anywhere from 23% to 77% of their income on the care of their infant, depending on the state. For single mothers in the median income range, this could be from 29% to 94%.

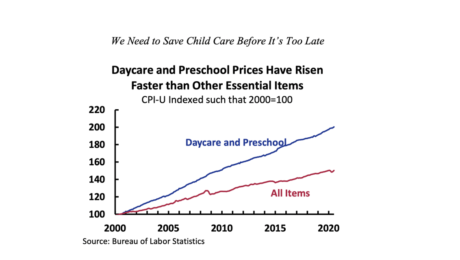

Childcare costs in the U.S. are exponentially higher than its OECD counterparts. The U.S. spends less that half the amount of its GDP on childcare in comparison to the average of other OECD nations. In fact, the U.S. spends 3 to 6 times less than France, New Zealand, and all the Nordic countries. Where in many OECD nations, childcare is free or very inexpensive, making it widely accessible, in the US, the accessibility and quality of childcare for working parents is contingents upon their economic status. A lack of accessible and affordable childcare leads to lost earnings for parents, an estimated $20 – $35 billion in total, according to the Economic Policy Institute. This in turn translates into a loss of roughly $4.2 billion dollars in federal and state tax revenue per year. The cost of childcare is skyrocketing past the rate of inflations as well, between the years 2000 and 2020, day care and preschool costs rose double that of inflation.

Extensive research has shown that accessible and affordable childcare has strong positive economic benefits and contributes to the well-being of children and parents. Without the benefit of accessible and affordable childcare, many parents, mostly women, experience reduced earnings for the duration of their careers. This also contributes tremendously to the gender wage gap. Furthermore, according to a 2015 Council of Economic Advisors report, every dollar spent on childcare and early education carries the potential to yield eight dollars in societal benefit.

Childcare workers also struggle due to low wages, poor benefits, and precarious working conditions. In 2017, an average childcare employer kept 13 workers on payroll, each of whom earned just $20,886 on average in annual compensation. In 2019, the median hourly wage of U.S. childcare workers was $11.65, a near-poverty wage. Nonetheless, employee’s compensation is the highest cost for these establishments, as they must maintain a low ratio of children to caretaker, which varies from state to state. Cost of rent is another major expense for childcare providers, but reducing the size of the facility, and therefore the rent costs, is not a viable option as crowding and lack of outdoor space has been shown to increase the risk of infections and injury within the centers.

There is still a great amount of work to be done in the U.S. The CARES Act passed in March of 2020 provided $3.5 billion of funding to states in childcare subsidies for low income families. Additionally, the inclusion of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) provided $2.3 billion to childcare providers across the country, enabling 460,000 childcare workers to remain employed. Although these measures were helpful, much more assistance is still needed. For the most part, smaller childcare centers and home-based programs were not able to access these PPP funds at all, with only 29% of them receiving these funds. The vast majority of childcare operations across the board, many of which single-person operations, were also not able to access these PPP funds at all. The HEROES Act, passed in the House of Representatives in May, would provide another $7 billion in relief for childcare centers and $850 to fund child and family care for essential workers. However, this legislation has stalled in the Senate.

This pandemic has dealt a devastating blow to an already inadequate childcare system in the U.S. Without desperately needed assistance, the U.S. faces the potential of losing 80% of its childcare capacity. This will in turn deprive working parents of the critical services and infrastructure needed for the economy to recover. Read the complete report “We Need to Save Child Care Before It’s Too Late.”

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Policy, U.S.

Spirals of Inequality: A Women’s Budget Group Special Report

The Women’s Budget Group Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy, launched in February 2019, is an expert-led project aimed at developing economic policies that promote gender equality across the United Kingdom. The Commission utilizes a number of avenues and tools to achieve this objective, one of which is the recent release of the report “Spirals of Inequality: How Unpaid Care is at the Heart of Gender Inequalities.”

This first report released by the Commission seeks to trace the problem of how gender inequalities in the UK are produced and maintained by observing the problem through the following perspectives:

Unpaid Work: Women Continue to do the Lion’s Share

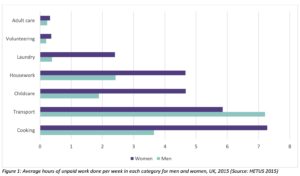

The unequal division of labor within unpaid care work is at the heart of gender inequality in the UK, with women taking on 60% of the unpaid work on average. This includes care work, cooking, and cleaning among other tasks.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

This proportion of unpaid work has increased between 2000 and 2015. Seeing that unpaid work is indispensable to both the function of society and the economy, feminist economists have argued for unpaid work to have recognition in systems of national accounting. These campaigns have led to the UK Office for National Statistics to develop estimates; the most recent from 2014 valuing unpaid care work £1.01 trillion.

Limiting Opportunities for Paid Work: Women More Likely to Work Part-Time and Earn Less

This phenomenon puts a disproportionate strain on women and contributes to gender inequality. Mothers with young children are 3-4 times more likely to work part-time, and women, in general, are far more likely to be in precarious forms of employment such as temporary work. This is especially true for women of color. The part-time work conundrum is driving the gender gap, and on average women earn 43% less than men. Furthermore, a pay gap of 8.9% persists, further exacerbating this issue. Again, this being more predominate with women of color.

Despite women becoming increasingly educated, they persist in being overrepresented in low-wage sectors of the economy such as health and social work. Feminist economists have argued that a reason behind this is such sectors are viewed as an extension of a women’s “natural” work.

These issues create a perpetual cycle that allows for the inequality between men and women to continue.

Life Course Implications: Benefits Make Up a Larger Portion of Income and Austerity Hits Harder

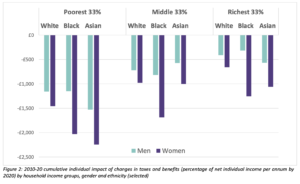

Among single households living in poverty, those led by women make up for 86%. Furthermore, pensioners living alone are far more likely to be at the poverty level if that individual is a woman. Since tax reforms began in 2010 throughout the UK, women have also been hit hardest. These benefits make up a large portion of women’s incomes and cuts to these benefits and tax giveaways benefit those fitting into a higher wealth bracket.

Public Services: Women Hit Hardest by Cutbacks

Cuts to public spending throughout the UK have also hit women disproportionately hard, as women are most likely to utilize public services. The poorest families and especially those in poverty-level households led by women have taken a particularly bad hit; many single mothers have had to cut living standards by up to 10% as a result of a cut to public services between 2010 and 2017.

Furthermore, these cuts have put a greater burden on family members to provide care for the elderly members of their family, much of this falling onto female members. This often comes at the expense of their own employment.

Violence Against Women: “Cause and Consequence” of Women’s Economic Equality

All of the factors that lead to the economic disparity between men and women also make it increasingly difficult for women to leave abusive partners. Furthermore, poorer households have higher rates of domestic abuse, and this perpetuating poverty limits women’s options while increasing their vulnerability.

Moving Forward: Next Steps for the Commission

The WBG Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy is striving to develop an alternative economic approach aimed at addressing these issues. Through this initiative, they aim to build an economy that is desirable, economically feasible, and necessary for fairness, sustainability, and resilience. To learn more about the Commission and its work, sign up to attend the upcoming webinar “Creating a Caring Economy: A Call to Action” on September 30, 2020.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy

LTC Sector Faces a Number of Challenges, Today and Going Forward: An OECD Report

OECD Health Policy Studies has released a 2020 report “Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly.” This report addresses a number of important issues while acknowledging the tremendous impact that COVID 19 has had on elderly people and their caretakers. Across OECD countries, more than one out of every six individuals is above the age of 65, and of those roughly 60% live with multiple chronic conditions, making them even more susceptible to the potentially deadly impacts of the virus. Furthermore, many elderly individuals struggle with sufficient access to social support and lack the ability to properly deal with the mental strain of living in a world being affected by a global pandemic.

Beyond these strains, there is a crisis in workforce shortcomings of the Long Term Care (LTC) Sector, which becomes even more problematic in light of the fact that an estimated 50% of COVID 19 related deaths are occurring in LTC facilities. This OECD report begins by addressing many of these shortfalls within the LTC sector, and policies that have the potential to address them.

Within three-quarters of OECD countries, the aging population has outpaced the workforce within the sector since 2011. This is the case even in the countries that have a higher workforce supply than the OECD average such as Japan and the U.S. Within the sector, women make up 90% of the LTC workforce. Attracting a younger workforce has been particularly difficult, and on top of that maintaining workers over the age of 50 is also a challenge. This is even more concerning given that the median age of LTC workers is currently 45.

Many OECD nations have made moves toward relocating their elderly out of facilities and back into the community. This is provoked by the desire to match the preferences of their elderly populations with home-based care, in addition to containing LTC spending. However, a lack of home-based workers has made this challenging, and LTC institution-based workers remain representative of the sector’s workforce across the OECD. This is in large part due to the fact that these institutions cater to the most disabled, which requires a larger workforce. Furthermore, many community-based solutions are not yet equipped to take in these types of complex cases.

The aging of the postwar “baby boom” generation is a factor that will contribute to the increased need for LTC workforce. This also contributes to the predicted increase in labor shortages in the sector to meet the needs of this population going forward. Further, unpaid informal care workers, like that of family members that would care for this aging population, have seen an increase in their own professional workload burdens. When the workload of professional life and caretaking becomes too great, LTC facilities are a means in which to relieve some of that strain. Additionally, as birth rates decline, families become smaller and more women are pursuing professional endeavors, the availability of informal caregivers for the aging population decreases looking into the future. This contributes to another foreseen LTC workforce shortage in the future.

These shortages call for an increase in recruitment within the LTC sector. As the sector workforce ages, attracting younger workers has proven difficult as they, mostly women, are drawn to sectors that have a more appealing image such as a child or hospital care. Additionally, LTC jobs are still widely considered to be feminine positions, and the sentiment on this subject matter has been slow to change.

Foreign-born workers play a significant role in recruiting and retaining LTC workforce. They are highly over representative within LTC across the OECD when compared to other care sectors, and many of them are young, Often, they tend to come into the sector with high levels of skill sets, even overqualified. Micro-econometric analysis has shown that in the U.S. and the UK, these foreign-born workers have higher retention rates than others within the sector.

In terms of recruitment, drumming up interest in the available positions is also problematic. In some cases, many vacancies receive no applications at all. On top of this, recruiters often have a difficult time identifying qualified candidates out of those that do apply.

In order to address this, many countries have focused on four main policies:

– Target recruitment to the traditional pool

– Improve the Image of the sector

-Recruit outside the traditional pool

-Increase the recruitment of for foreign-born workers

Overall, better policies are needed in order to improve recruitment within the LTC sector, and thus far few OECD nations have implemented policies in order to do so. By addressing these issues addressed within the first section of this report, there is potential for effective improvement.

- Published in elderly care, Long Term Care Sector, Policy

Webinar (09/30/2020): Creating a Caring Economy

On Wednesday, September 30th at 10:00 -11:30 am BST, the Women’s Budget Group (WBG) will be a hosting a webinar titled “Creating a Care Economy” which will discuss the work being done within the Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy and the launch of its digital final report. This report comes at a unique time in our history, amidst a devastating global pandemic and on the brink of a harsh economic recession. The commission has taken this unprecedented time to pose the question: “do we really want to go back to business as usual?”

The Women’s Budget Group, (WBG) based out the United Kingdom, is an independent network of policy experts, academic researchers, and campaigners, harboring a vision of a “caring economy that promotes gender equality.” This non-profit organization works hard toward producing vigorous analysis intended to influence policymakers while also building the knowledge and confidence of individuals to talk about feminist economics. WBG achieves this through offering training and creating resources that are accessible and informative.

In February of 2019, WBG launched the Commission on a Gender-Equal Economy. This project works proactively to develop policies that promote gender equality across the UK, and is the first of its kind. This commission is chaired by Diane Elson.

The commission has thus far produced a number of helpful resources. To begin they have produced a short video entitled Spirals of Inequality which delves into how unpaid care is at the heart of gender inequality. This video is also accompanied by a short brief and a longer, more in-depth accompanying paper. They also have an ongoing blog, and have commissioned a number of papers focusing on four areas: Public Services, Social Security and Taxation, and an Enabling Environment. Additionally, they have gathered a number of calls for evidence, which collects evidence from many experts in varying sectors.

The final report that will be explored within this upcoming webinar will lay out a roadmap in which to build a more caring economy, outlining out the how, the why, and acting as a call to action across all the four nations encompassed within the United Kingdom.

Learn more and register for the webinar here.

- Published in Events, Gender-Equal Economy

Biden’s Care Plan Has the Potential to Change Care Work in the U.S. for the Better

Joe Biden has officially accepted the Democratic Presidential nomination, and he and his team plan to make substantial investments in the infrastructure of care in the U.S. if he wins in the Presidential election. The potential of this plan to provide much-needed support for care workers, both paid and unpaid, is more important than ever amidst the pandemic.

Even prior to this pandemic, the U.S. has long suffered a caregiving crisis. Family caregiving needs often come with incredible financial, emotional, and professional burdens. Professional caregivers, disproportionately women of color, have long been underpaid and undervalued. The pandemic has exacerbated these issues, leaving parents struggling to find the care services needed while juggling careers. There are a number of measures that have been proposed by the Biden team to address the many issues currently plaguing the overall care system in the U.S. today.

Elderly individuals in nursing homes are feeling an increasing need to be cared for at home rather than in community living situations where they are more vulnerable to COVID-19 exposure. The Biden care plan addresses this by aiming to close the existing Medicaid gap to allow for home and community-based care services while creating a state innovation fund for cost-effective direct care services. This will provide more affordable and accessible care on that front. This step will also help to alleviate the extensive waitlists now existing for those under Medicaid to enter home and community care programs, providing these services for 800,000 individuals. If implemented properly, this initiative allows the opportunity to provide more functional care systems that grant greater independence to elderly individuals, while also freeing many unpaid care workers, such as family members, to pursue professional endeavors.

This plan also proposes increasing wages and benefits for caregivers and early childhood educators while providing opportunities for training, professional growth, and unions. This particular initiative takes into consideration the fact that early childhood development is incredibly important, and quality childcare is essential for children to grow into healthy, productive members of society. Universal preschool will also be provided via tax credits and sliding scale programs. Furthermore, included is an investment into safe and developmentally appropriate childcare facilities, including bonus pay for those providers that operate non-traditional hours, such as early mornings, late evening, and weekends. By increasing access to childcare centers with more flexible hours, the burden for many families will be lifted; currently, many parents that don’t work traditional Monday through Friday hours are left scrambling to find adequate care. These initiatives overall will have significant positive impacts on working parents, particularly women. Far too often, women find themselves sacrificing professional progression and development due to the constraint of inadequate or unaffordable childcare.

For those parents who grapple with the decision to further their education as a result of unaffordable and reliable care, investment in childcare centers at community colleges is also included in this plan.

Lastly, expanding the awareness of the Department of Defense fee assistance childcare programs so that all military spouses have the ability to pursue their professional development and education.

In order to pay for these initiatives, the Biden team has estimated a cost of $775 billion over the span of ten years, to be funded by rolling back certain tax breaks for those earning over $400,000 annually. A $5000 tax credit or Social Security credits for those providing unpaid care for members of their family is also proposed. Further, the plan seeks to offer low- and middle-class families up to $8000 in tax credits to assist in paying for childcare. For those that choose not to claim this credit, high-quality care is to be provided on a sliding scale, where it is estimated that families will not pay over $45 per week.

Although this plan is incredibly ambitious, and its implementation is not a guarantee, it sets a precedent that has been long lacking within the U.S. care work sphere. Implementation of these initiatives on any scale would prove beneficial to both the paid and unpaid care economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy, U.S.

Reflections on Parental Caregiving and Household Power Dynamics

A growing concern in many countries is an aging population and an increase in the number of elderly in need of long-term care. However, the impact of elderly care on the well-being of care providers remains relatively understudied. One of the primary factors which complicate analysis is that a majority of elderly care is provided informally by family members, with adult children often comprising the largest share of care providers. The pervasiveness of unpaid care due to cultural or family ties has even limited the development of long-term care insurance in economically advanced regions like Europe. However, while children may provide an informal safety net, parental caregiving is a time-intensive task and must be met by adjustments in leisure or work hours on the part of the care provider. Hence, in order to understand the full macroeconomic implications of growing elderly care needs and the appropriate policy response, it is imperative to understand how households cope with these caregiving needs.

Economic models of elderly care have focused almost exclusively on inter-generational bargaining between parents and children or bargaining among siblings. However