Save the Date: Women & Migration Global Mapping Report

On March 1st the Women in Migration Network and Friedrich-Ebert- Stiftung is launching a new report mapping organizations working on gender and migration around the world “No Borders to Equality.”

This new report has mapped over 300 organizations around the world working at the intersection of gender and migration. It is based on a survey and interviews that identify key priorities, concerns, advocacy and mobilization, and which reveal the tremendous potential and importance of bringing a gender perspective to the dynamic issues of migration today.

In addition to the report (which will be available in English and with an Executive Summary in English, Spanish and French), an interactive website is being developed to help in identifying and locating these key groups in the various global regions.

To accommodate global time zones, the launch event will take place at two different times. You can register for either event:

(Asia Focus) 5pm PHST/10am CET

Register at: http://bit.ly/WIMNFESwebinar1

(Global Focus) 10am EST/4pm CET

Register at: http://bit.ly/WIMNFESwebinar2

– traducción al español

– interprétation en français

Be sure to attend this exciting event to learn more.

- Published in Events, Gender Inequalities, Policy Briefs & Reports

A Narrative on Care

In 2018, the Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) Project’s Understanding and Measuring Care (UMC) Working Group set out to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of care work and the well-being of caregivers in the context of South Korea. The group used a unique qualitative method combining in-depth interview and oral historical approach to investigate care as a continuously recurring activity throughout one’s life course and a necessary part of human existence. As part of the project’s qualitative field work and with the help of Gallup Korea, the UMC Working Group conducted 96 interviews between May – December 2018, bringing together 96 comprehensive narratives of care work in the South Korea context.

The CWE-GAM Project’s qualitative field work in South Korea conducted 96 in-depth interviews of paid and unpaid caregivers to provide useful care narratives based on the Korean context to inform macro-modelling. The qualitative research team interviewed 25 family caregivers of the elderly, 20 family caregivers of children, 20 paid care workers for elderly, and 31 paid care workers for children. The interviews of family caregivers focused on the decision-making process and evaluation of care arrangements for the elderly and children. In-depth interviews were combined with an oral historical approach to gain a deeper understanding of care work, emphasizing active listening to gain a more holistic understanding of the narrator’s life story on care. Interviewees were also asked about their experiences with caregiving. The interviews of paid caregivers focused on dual care burdens in terms of paid care work in addition to unpaid care work in the home. To learn more about the CWE-GAM Project’s qualitative field work in South Korea, read the Qualitative Methodology Report by the Care Work and the Economy UMC Working Group.

The following is one of the 96 stories. The respondent, Sung, lives with and cares for her mother, who was diagnosed with dementia about ten years ago.

*******************************

Date: May 29, 2018

Seocho-gu, Seoul

Interviewer: Hyuna Moon

Interviewee: Sung (pseudonym)

Sung, born in 1968, is 50 years old. She has a son and a daughter. They are both over 19 years old. One is attending college, and the other is studying for the college entrance exam. She is currently living with her children and her mother. As for siblings, she has one younger brother who is married. About ten years ago, Sung’s mother was diagnosed with dementia. Sung’s dad cared for her mom in the beginning, but her dad was also later diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Sung thus decided to move into her parents’ house to live together. It was by the time her first child entered middle school and her second child reached the upper grades in primary school. Her dad died four years ago, and she now looks after her mother. Her mother became a grade 3 beneficiary of the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTC) in her initial stage.

When Sung found out that her parents were ill, she didn’t think about passing the care duty to her brother. The siblings first considered making living arrangements so that each of them would live with one of their parents, for instance, Sung living with their dad and her brother living their mom, but their parents did not want this; they wanted to live together, not separately. Sung also felt that she ought to take care of her mother because of her ten years of experience living abroad, away from her parents. Sung has never thought that taking care of her frail parents is a son’s or a daughter-in-law’s duty. She didn’t think it was her brother’s duty to live with their parents and provide support. Nonetheless, her brother has taken up the role of financially supporting their parents. According to Sung, this was not negotiated but naturally happened. Sung and her brother also tried having their parents stay at her brother’s house during weekends, but it was always troublesome because he was not familiar with the situation, thus constantly calling up Sung for help. This weekday/weekend division of care duty did not work for them. Sung’s mother started going to the elderly daycare center from 2015 after her husband died. Her mother moved to a different center once because the center was located too far away from Sung’s place. Sung’s mother attended the first center for two years. When the center stopped running its shuttle bus to Sung’s house, Sung had to drive her mother to and from the center for a year. During that time, she had to hire a private caregiver who was responsible for driving Sung’s mother home in the evenings.

The hired caregiver also prepared meals and did some simple house chores for Sung. Sung paid her 1,000,000 KRW ($850 USD) every month, in addition to the monthly senior center fee of 300,000~400,000 KRW ( $250 – $335 USD). Other care-related expenses include Sung’s mother’s caregiver’s wage and other care services such as home-visit bathing service on weekends, food, medical bills and daily necessities such as diapers and etc., totaling about 2,000,000 KRW ($1,700 USD) per month. Sung’s brother helped to cover their mother’s care-related expenses, as Sung’s own income also had to cover her children’s education and living costs.

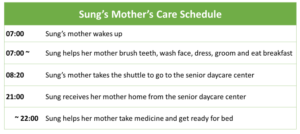

Description of Care Arrangement

Sung’s mother goes to the senior daycare center on weekdays and receives a home-visit bathing service every Saturday morning. The current elderly care center runs a shuttle that arrives at Sung’s house at 8:20 am to pick up her mother and to ride her back home at 9 pm. Sung’s mother is using the center service fully, spending the whole day at the center. Sung takes care of her mother after 9 pm until she goes to bed. When her mother comes back home, Sung helps her take medicine and changes her clothes and diapers. Her mother sleeps before 10 pm. Sung said her mother usually gets home tired after engaging in a variety of programs and activities offered all day long at the center.

Sung thinks her mother’s enrollment at the day care center is better than her staying at home and being bored. Sung said the most difficult part in caring for her mother happens at night, when her mother wakes up due to defecation. In such instances, Sung has to respond quickly to avoid what would otherwise become an even longer night, with her having to clean up the remains that will be all over the place. It got worse since last year and called for the most attention when caring for her mother. Nevertheless, Sung said her mother’s situation of dementia is not too bad, considering that some people with dementia can be very aggressive and easily agitated. Sung’s mother is relatively well-behaved, but she has this stubbornness which makes it difficult for Sung to help her get washed and change her underwear for she finds these to be a shame.

Sung said weekend care is tougher than weekday care because she needs to prepare food for every meal. The LTC-funded caregiver visits every Saturday to provide bath support, which is of great help, but Sung also needs to partake in the bathing assistance, requiring her presence.

The Cost of Caregiving

For Sung, it was an overload of work when she started supporting her parents by living together, while also having to care for her two adolescent children and working for her job at the same time. Sung said she had suffered from depression a few years ago due to the high stress of managing all her responsibilities. She had to seek psychiatric and medical treatments to overcome her depression.

Sung is considering sending her mother to the 24-hour nursing home as her health status is gradually deteriorating. She has applied for the institution for her mother’s stay, but she faces a long waiting list with more than 200 people. Sung said the reason for such a long waiting list is because this is a public nursing home, which is believed to provide better quality care and facilities.

Two years, she said, is what she thinks as the maximum number of years that she would be able to live with her mother if the current situation holds. But if it worsens, that is, if her mother’s dementia symptoms get worse, Sung will also consider sending her mother to some other facility with a shorter waiting list but also with lower quality of care.

She said that she would have to set a deadline to her caregiving for her own sake. She does not want to spend the rest of her 50s trapped with the care duty to her mother. Her children are now independent adults. Sung wants to start living her own life. She also feels she has done enough for her mother, her families and relatives all know it, and nobody will blame her for making this decision. Sung said because she is also a human, she needs to have her life and has the right to pursue it instead of sacrificing for her family.

****************************

See the surveys utilized for conducting this research below:

2018 South Korea Eldercare and Childcare Household Survey – Childcare

2018 South Korea Eldercare and Childcare Household Survey – Eldercare

A New National Model for Preschool and Childcare in the U.S.

Frustrated with decades of inaction at the national and state level, residents of Multnomah County, Oregon put a measure on the ballot this past November to create a free, year-round, universal preschool program for all three and four year-olds in the county. Approval was resounding, the vote nearly two to one in support.

Despite years of compelling evidence for universal preschool as a powerful economic development strategy that improves educational outcomes while fighting poverty and inequality, as well as gender and racial disparities, the U.S. lags far behind many nations in the provision of early childhood education and care. But – unlike other desperate needs such as affordable housing and health care – early childhood education is relatively inexpensive, making it possible for a city or county to mount its own program.

The preschool model being created for the city of Portland, and the rest of Multnomah County, should set a new standard for public preschool programs in the U.S., meeting the needs of children, their families and preschool staff. To help children thrive and obtain the most from their later education, Multnomah County will work with a range of providers to offer a high quality program, in different languages and cultures, and in a variety of settings, including schools, centers, and family child care. The program will attain full universality within ten years, prioritizing the enrollment of children from communities of color and families with lower incomes in the early years as the program builds.

To ensure that the program works for families, they’ll also have a choice of schedules, including full and part-time, school year or year-round, and weekends as well as week days, for up to five days a week. All children may attend without cost for up to six hours a day, with ten hours a day free for families in the lower half of the income distribution.

To retain the skilled, experienced, dedicated – and almost entirely female – staff so critical to quality, teachers’ salaries will double the going rate, to equal those of kindergarten teachers. The wage floor for all classroom workers, including aides and assistant teachers, will be significantly above the minimum wage, starting at just under $20 an hour in the autumn of 2022 when the first children will be enrolled.

No public preschool system in the U.S. has yet paid a living wage to all staff members, despite cripplingly low levels of staff retention. Economist Catherine Weinberger has shown that, in the U.S., four of five employed women with college degrees in early childhood development and education do not work with young children. By contrast, high proportions of college graduates educated as nurses, accountants and others work in jobs that draw directly on their academic training.

Further, Multnomah County’s new universal preschool program will be funded by a county income tax levied on approximately eight percent of the county’s highest income households, addressing skyrocketing economic inequality and the forty-year concentration of income at the very top.

The Multnomah County ballot measure campaign was supported by an undeniable coalition of teachers, unions, organizations representing communities of color, civic and feminist groups, small business owners and environmental advocates– not to mention galvanized parents, child care workers, preschool providers, public health care workers, doctors, economists, school board members and elected officials. Two separate campaigns worked independently for years to prepare a ballot measure, emerging to find themselves aimed at the same election. The more ambitious was led by the Portland chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America while the other was headed by a philanthropy, called Social Venture Partners, working with an elected County Commissioner. The two campaigns were able to merge on their strongest combined program, after the bolder plan gathered thirty-two thousand signatures, more than enough to qualify for the ballot.

Key to our success, I believe, was creating a program that works for children, parents and workers. Too often in the U.S., fear of raising taxes has led to small, part-time and ill-paid programs serving only the least advantaged, and supported by a limited base of advocates for children from lower-income households. High quality, universal programs are not only more successful at improving educational outcomes for disadvantaged children, but enjoy the popularity necessary to sustaining funding into the future while allowing parents to work more hours or gain additional schooling.

This blog was contributed by Mary C. King who is Professor of Economics Emerita at Portland State University, Vice-President of the Oregon Center for Public Policy, Co-Chair of the Oregon Scholars Strategy Network and a founding board member of Family Forward Oregon. She has spent the past three years campaigning for universal preschool in Multnomah County, where voters decisively approved the creation of a free, year-round, full-day universal preschool program on November 3, 2021.

- Published in Child Care, U.S., Universal Preschool

Care Work and the Economy: Fieldwork in South Korea

The 2018 fieldwork for the CWE-GAM project aimed to understand and measure care work in the South Korean context in order to inform gender-aware care macroeconomic models. The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys. The quantitative surveys include two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers in eldercare and childcare (Paid Care Worker Survey) and two sets of questionnaires for the unpaid care providers in the households for eldercare and childcare (Care Work Family Survey). The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and care recipients.

PAID CARE WORK SURVEY

The Care Work and the Economy Paid Care Work Survey includes two sets of questionnaires for eldercare and childcare workers and a 24-hour time use diary. A purposive sampling method was used to sample 600 paid care workers, 300 eldercare workers and 300 childcare workers, because the exact size and distribution of paid care workers in Korea are unknown. Paid care workers are defined as those working in institutional settings, at the care recipients’ home, and informal workers working without formal contracts. The sample targeted those providing care of the elderly and children’s daily lives, excluding kindergarten teachers and health care workers at hospitals and medical eldercare facilities. The sample of paid care workers associated with institutions were allocated to reflect the national distributions of eldercare facilities and daycare centers, and the sample of informal care workers were equally allocated across regions.

The Paid Care Worker Survey collected detailed and comprehensive information on the care work provided by paid care workers. The stylized questions and time use diaries of paid care workers collect information on the type, intensity, duration, and evaluation of care work from the perspective of paid care providers. The survey aimed to investigate the characteristics and working conditions of paid care workers, including their background, condition of contract, working environment, task arrangement, and subjective evaluation of the working conditions, and their well-being. The 24-hour time use diaries were collected to provide insights on how the day of a care worker is constructed and how care work is associated with other domains of daily life and time use, which can be analyzed in tandem with the stylized questions on the well-being of care workers.

FAMILY CARE WORK SURVEY

The Care Work Family Survey also consists of two sets of questionnaires for main care providers in the household engaged in childcare and eldercare respectively. 1,000 cases of main care providers in the household were interviewed (500 cases for childcare, 500 cases for eldercare) using a stratified cluster sampling method. Because it is not possible to know the distribution of the population of people who provide unpaid care in a society, children aged below 10 and the elderly aged over 65 were treated as the target population from which to draw the sample. Based on the distribution of the 2018 National Resident Registration Data in Korea, we allocated the number of target households to each area, identified eligible households with elderly or children in need of care, and then selected eligible respondents within the selected households.

The Care Work Family Survey was developed to provide a detailed and comprehensive picture of the care arrangements in South Korea. The survey aimed to investigate how care provision is arranged for the children and the elderly and why it is arranged in such ways. Therefore, the survey collects information from the main care provider, not the care recipients themselves, as it is often the case that the main care provider is the one who knows most about the care arrangements.

After screening for eligibility, respondents were asked questions on their demographic characteristics and information on the respondent, care recipients and other household members. Respondents were asked about the specific activities involved with their care work including frequency, subjective intensity, preferences and willingness to engage in the activities. Information on care arrangements were collected as well including how the care work is shared within the household, whether there are any gaps of care provision, the history of caregivers, use of care services, and decision-making of using care services. Other information such as financial responsibility and burden, experience and evaluation of care work, dual care burdens and well-being of caregivers were collected.

IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

The purpose of the in-depth interviews of paid and unpaid caregivers was to provide useful care narratives based on the Korean context to inform macro-modelling. The qualitative research team intervened 25 family caregivers of the elderly, 20 family caregivers of children, 20 paid care workers for elderly, and 31 paid care workers for children. The interviews of family caregivers focused on the decision-making process and evaluation of care arrangements for the elderly and children. Interviewees were also asked about their experiences with caregiving. The interviews of paid caregivers focused on dual care burdens in terms of paid care work in addition to unpaid care work in the home.

SIGNIFICANCE AND LIMITATIONS

The fieldwork for paid and unpaid care work in Korea was designed and conducted to investigate the nature and context of care work in Korea. The Paid Care Worker Survey and Care Work Family Survey have distinct characteristics that contribute to enhancing our understanding about the experience of caregiving in Korea. First, the set of questions that have been developed can be commonly applied to caregivers regardless of the type of care work or the subject of care to enable comparative analysis on the experience of caregiving. Second, not only the caregiving situation, but also the broader aspect of the caregiver’s life including the preferences and attitudes of the caregiver have been studied. Third, the surveys collect detailed information on how care is arranged. Lastly, a caregiver focused 24-hour time use diary has been developed to understand which activities could be considered as care.

This fieldwork only included certain types of caregivers due to the limited budget, time, and scope of the fieldwork. For instance, the sample did not include caregivers for the disabled, caregivers who work at hospital settings, and migrant care workers, despite their importance. Also, as the family survey for childcare limited the respondents to ‘mothers’, and consequently fathers and grandparents were excluded. We hope that the future rounds of surveys can be extended to have a larger sample size and to include a broader range of caregivers. Questions explored in this fieldwork provide important information about the experience of caregiving in Korea, and we hope the fieldwork in Korea can inform fieldwork in other countries.

Learn more about care arrangements and activities in South Korea based on our analysis on the 2018 Care Work and Family Survey here.

This blog was authored by Bong (Regina) Sun Seo, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group

Hawai’i and Canada Provide Lessons for Feminist Economic Recovery from COVID-19

The need for an inclusive, gender-equitable recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic is slowly gaining recognition as it lays bare and exacerbates inequities in economic, social, health, and environmental policies and programs.

The Hawai’i State Commission on the Status of Women convened a working group to develop and share principles and practices for implementing a gender-responsive and feminist response to COVID-19, culminating in the publication of Building Bridges, Not Walking on Backs: A Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for COVID-19.

Similarly, the YWCA Canada and the Institute for Gender and the Economy (GATE) at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management published a joint assessment, A Feminist Economic Recovery Plan for Canada: Making the Economy Work for Everyone. The plan highlights critical principles and provides actionable recommendations for the government to develop and implement post-pandemic recovery policies that are equitable and inclusive of all marginalized people.

Together, the Canadian and Hawaiian plans provide a roadmap to recovery through gender-transformative policy-making. Both are built on an intersectional analysis of the impact of the pandemic and call for an approach to economic recovery that examines and confronts the root causes of inequality, including but not limited to patriarchy, ableism, queerphobia, white supremacy, colonialism, classicism, and racism.

A recent brief by Alexandra Solomon, Kate Hawkins, Rosemary Morgan of the Gender and COVID-19 Working Group describes the intersecting, complementary, and mutually reinforcing elements of the two frameworks and echoes the call for feminist economic recovery. It provides a collection of best practices for the core tenets of post-pandemic policy-making which should be echoed and adapted by policy-makers from other settings.

Key Recommendations to Policymakers:

- Pandemic responses should be underpinned by data that is disaggregated by sex and other markets of inequity at the national and subnational level. This data should be made public and used in decision making.

- Women-led organizations, feminist academics and women’s experiences and ideas should be at the center of recovery efforts in government bodies, official consultations and online spaces.

- The provision of universally accessible, free childcare and long-term eldercare should be central to economic recovery plans and attempts to ‘open up’ the economy. Precariously employed immigrant care workers should be provided with an expedited path to permanent resident status.

- Austerity-induced budget cuts should be avoided as they impact most greatly on the poor, women and other marginalized groups. Instead policy-makers should strengthen public welfare assistance (such as unemployment benefit) and labor rights (such as paid sick leave, family leave and a guaranteed living wage).

- Special stimulus funds should be designated for high risk groups, such as those who are not eligible under existing government schemes, are disproportionately experiencing financial hardship and poverty, and already face barriers to accessing their rights to health, safety, independence and education.

- Invest in universal, affordable, and sustainable access to water, sanitation, hygiene and housing, and prioritize closing the gender digital divide.

- Support women in female dominated economic sectors particularly hard hit by the pandemic as well as historically marginalized women workers, such as Indigenous women and sex workers.

- A feminist recovery is aligned with a ‘green’ recovery and the two should be considered in conjunction.

- Revisions of fiscal and monetary policies should be taken as opportunities to address inequality in wages, employment, and quality of life.

- Health systems should be restructured to focus on Universal Health Coverage and to address problems in service access and quality due to sexism, colonialism and white supremacy. Tackling the social determinants of health should be a priority.

- All hate, violence, and oppression against women, gender-diverse people, and Indigenous, Black, and racialized communities must be addressed in the COVID-19 recovery.

READ FULL BREIF:

Solomon, A., Hawkins, K., and Morgan, R. (2020). Hawaii and Canada: Providing lessons for feminist pandemic recovery plans to COVID-19.The Gender and COVID-19 Working Group.

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in COVID 19, Policy, Policy Briefs & Reports

Caregiving in Crisis and How to Fix It: Special Issue from The American Prospect

Last month, the Prospect released a special issue featuring a series of articles surrounding family care,“Caregiving in Crisis and How to Fix It.”

To accompany this issue, a special event was hosted by the Prospect in which various activists, writers and caregivers discussed family care, child care, elderly care, paid family leave to provide care, and long term support for caregiving services.

This event featured:

David Dayen, executive producer for the Prospect

Ai-jen Poo, co-director of Caring Across Generations,

Lynnea Redmon-Williams, a caregiver working fulltime

Tasmiha Khan, Prospect contributing writer

Rhacel Salazar Parreñas, Professor of sociology at the University of Southern California

Brittany Gibson, Prospect writing fellow

See the video below for the entire discussion:

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Long Term Care Sector, Special Issues

Global South Women’s Forum 2020: Disrupting Macroeconomics

A Forum to Learn, Strategize, and Celebrate Visions for Economic Justice

December 14 – 18, 2020

The International Women’s Rights Action Watch (IWRAW) Asia Pacific is hosting this year’s Global South Women’s Forum on Sustainable Development (GSWF 2020) as an online space for learning, strategizing and celebrating feminist visions for economic justice.

IWRAW is inviting proposals to develop and lead thematic sessions at this year’s virtual Global South Women’s Forum on Sustainable Development, 14-18 December 2020. This year’s forum will be themed around feminist macroeconomics, power and justice. IWRAW invites proposals from diverse feminists and social justice activists, organizers, artists, and practitioners from across the Global South to lead and develop sessions. They are particularly interested in hearing from people representing marginalized groups or advocating for underrepresented issues.

This year’s theme is Disrupting Macroeconomics, with a focus on feminist macroeconomics, power, and justice, and the forum will be held online from 14-18 December 2020. Disrupting macroeconomics means shining a light on the connections between the global economy and gender inequality and discrimination – it means reclaiming policy spaces at all levels and demanding that the global economy be redesigned to advance equality, human rights, and international solidarity.

The deadline for submissions is 12 November 2020.

Visit IWRAW Asia Pacific’s blog post for more details on the theme, how to submit your proposals, and funding opportunities. If you have any questions, please feel free to contact IWRAW at gswf2020@iwraw-ap.org (with a copy to constanza@iwraw-ap.org).

- Published in Forums, Macroeconomics

Global Nonprofit Leaders on Why Women’s Time and Work Must be Part of Future Policy Choices

Last year, before the outbreak of COVID-19, the Hewlett Foundation teamed up with StoryCorps to record conversations with six nonprofit leaders working from Nairobi to Mexico City to make women’s lives, including paid and unpaid work, visible and part of economic policy decisions. Their professional endeavors—and personal motivations—help us see the different ways women experience day-to-day life, and are affected by social and economic changes, including the COVID-19 pandemic and prevention measures.

Maria Floro grew up in the Philippines and saw her parents treat her and her brother very differently. She was expected to help in the household work, including cleaning her brother’s room—something that nagged at her even when she was only four or five years old. Jenna Harvey watched her mother take on the majority of care work in her home and for her grandparents. It made her curious about gender and the unpaid work women do to make the world run.

Today, Floro is an economics professor at American University and runs Care Work and the Economy, a network of researchers interested in incorporating care work and gender into macroeconomic and social policies. Harvey is the global Focal Cities coordinator for Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing & Organizing (WIEGO). As a global network—with Accra, Dakar, Delhi, Lima, and Mexico City as focal cities—WIEGO helps street vendors, waste pickers, domestic workers, and other informal workers organize themselves and use research and analysis to urge local, national, and global policymakers to improve their working conditions and opportunities.

Memory Kachambwa’s first fight was with a boy on a bus outside her farming town near Harare, Zimbabwe. “Who appointed you to be captain of the bus?” she remembers telling him when he tried to take charge and told her to sit quiet. Today she runs the African Women’s Development and Communication Network (FEMNET) based in Nairobi. FEMNET’s 800 members in 46 African countries work to create an African society where women and girls live with dignity and equal rights.

In her StoryCorps conversation, Kachambwa speaks with Gretchen Donehower, who leads the Counting Women’s Work project at the University of California at Berkeley. As a teenager, Donehower told her mom she wanted to be the first female chair of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board. She now runs a global research project that has teams in 60 countries tracking how men, women, girls, and boys produce, consume, transfer, and save economic resources—including with a new tool developed to track this during the coronavirus.

Kachambwa and Donehower recall another health crisis that put a large extra unpaid care burden on women in sub-Saharan Africa: HIV/AIDS. Women, including grandmothers, were often the ones who cared for the sick and for orphaned children. Policymakers, they say, need to include the cost of women’s time caretaking to figure out how and where to allocate resources to respond to health and economic crises. The care economy, Kachambwa and Donehower agree, is part of the economy.

This blog was authored by Sarah Jane Straats from the Hewlett Foundation.

Original blog published by Hewlett Foundation on October 19, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Sarah Jane Straats.

- Published in Leaders in Non-profit, Special Issues

COVID, the Old and Canada-What’s Wrong With Us? A Massey Dialogues Discussion

A recent virtual presentation from Massey College, “The Massey Dialogues: COVID, the old and Canada – What’s wrong with us?” brought together a panel to discuss how the detrimental impacts of COVID-19 in Ontario and Quebec fall alarmingly onto the elderly population. In fact, 80 per cent of pandemic deaths in Canada have occurred among the institutionalized elderly, the highest proportion in the world.

Ito Peng joins this conversation as a special guest to discuss the pandemic and its impact on Canada’s Long Term Care (LTC) sector, and ways through which the dominant thinking around market value/productivity neglects to value the work that older adults have already contributed to the economy throughout their lives, and fails to recognize their role as keepers of history and caretakers themselves.

In this discussion, Ito Peng is joined by Massey Fellows Dorothy Pringle, Husayn Marani and Michael Valpy.

- Published in COVID 19, elderly care, Expert Dialogues & Forums