CWE-GAM Scholars Leading Two Panels During 2021 IAFFE Annual Conference

This week, the International Association for Feminist Economics (IAFFE) will hold its Annual Conference: “Sustaining Life: Challenges of Multidimensional Crises” starting on Tuesday, June 22nd, and concluding Friday, June 25th. This conference will provide a forum for scholars to discuss feminist approaches to constructing “inclusive and resilient economic and political systems and [sustainting] our environment” in the context and aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Care Work and the Economy Project will be leading two panel discussions on Wednesday, June 23rd and Thursday, June 24th: “Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” chaired by Elizabeth King and Ito Peng, and “Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” chaired by Young Ock Kim. In the discussions, CWE-GAM researchers will present gender-aware macroeconomic models, data collected from unique surveys of care providers and families, and microeconomic simulations used to better understand care work and the economy.

“Those Who Care: Improving the Lives of Caregivers and Workers” is scheduled for Wednesday, June 23rd from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time) and will contribute to ongoing efforts to “illustrate the intersectionality of care provisioning, economic growth, and distribution.” With an increasing need for care due to the rapid decline in fertility rates and aging population, South Korea offers a unique context to introduce models and analyze surveys given to households, child and eldercare workers.

There will be four papers presented in this panel:

“The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The Case of South Korea” by Cem Oyvat and Ozlem Onaran “introduces a post-Kaleckian feminist model to analyze the effects of public social expenditure and gender gaps on output and employment building on Onaran, Oyvat, and Fotopoulou (2019), and extending it with an endogenous labor supply and wage bargaining model.”

“The Quality of Life of Family Caregivers: Psychic, Physical, and Economic Costs of Eldercare in South Korea” by Jiweon Jun, Elizabeth King, and Catherine Hensly “examines the psychic, physical, and opportunity costs of caregiving within the family using data from a special-purpose national survey of 501 households conducted in Seoul in 2018.”

“Quality of Care, Commitment Level, and Working Conditions: Understanding the Care Workers’ Perspective” by Shirin Arslan, Maria Floro, Arnob Alam, Eunhye Kang, and Seung-Eun Cha uses “the 2018 Care Work Economy (CWE-GAM) survey data collected from 600 child and eldercare workers in South Korea [to] analyze patterns of commitment levels among [paid carers] in various settings such as private and public institutions as well as in homes of recipients by conducting tobit regressions and entropy econometrics for robustness checks.”

“Impacts of COVID-19 on Work-Family Balance in South Korea: Empirical Findings and Policy Implications” by Ito Peng and Jiweon Jun examines COVID-19’s unequal impact between men and women in South Korea using data from a survey distributed to “1,252 households with at least one child aged between 0 and 12 in June 2020 to find out how the first 2-month social distancing measure had affected their work, childcare arrangements, and their wellbeing.”

“Seeking Gender Aware Applied modelings: Case of South Korea” is scheduled for Thursday, June 24th from 3:30 to 5:00 pm (EDT time), which will share the results of gender-aware applied modelings and micro simulations for South Korea. The panel will discuss which fiscal policies are likely to be the most effective at reducing gender gaps in paid employment and which forms of public investment best contribute to reducing and redistributing unpaid work between genders and socio-economic groups.

There will be three papers presented in this panel:

“Child and Elderly Care in South Korea: Policy Analysis with a Gendered, Care-Focused Computable General Equilibrium Model” by Martin Cicowiez and Hans Lofgren presents the first care-focused and gendered model in the computable general equilibrium literature for Korea that “is built around a social accounting matrix (SAM) that covers non-GDP household services, singles out sectors for child and elderly care, and disaggregates households on the basis on care needs.”

“Care Support Ratios in Korea and the US” by Gretchen S. Donehower and Bongoh Kye takes a holistic view of care by including both paid and unpaid care for all age ranges and “create[s] [care support ratios] to understand the current care market and whether it is sustainable in the future…in two aging populations- Korea and the United States.”

“Towards a Caring and Gender-Equal Economy in South Korea: How much does the regulation of labor market working hours matter?” by Ipek Ilkkaracan and Emel Memis “use[s] a unique time-use survey on care arrangements by couples with small children in order to explore the potential of [the] reduction of full-time market work hours towards [the] narrowing of the gender gaps in paid and unpaid work.”

To learn more about the panels presented by CWE-GAM researchers and the IAFFE conference, please visit the IAFFE 2021 Annual Conference homepage and program.

This blog was contributed by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Conferences, Events, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, Gender-Aware Macromodels, Gender-Equal Economy, Macroeconomics, Maria Floro, Research, Rethinking Macroeconomics, Uncategorized, Unpaid Work

Making Care Count

The COVID-19 pandemic has informed our understanding of the care economy, exposing disproportionate inequities that must be addressed to alleviate the international erasure of care workers. These issues are addressed in the latest Susan and Michael J. Angelides Lecture, in which Naomi Klein moderates a discussion between Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal and CWE-GAM researcher Dr. İpek İlkkaracan on COVID-19 and the care economy.

We live in an economic system that has traditionally deprioritized and invisibilized care workers, many of which are women of color, migrant, and poor women. The economic crisis brought on by the pandemic has consequently given policymakers and academics “a once-in-a-generation opportunity to address [the valuation of care work] from an intersectional [approach],” states Congresswoman Jayapal.

The Care Crisis Exposed by the Pandemic Recession:

When mass unemployment hit during the pandemic, the cracks in the economic infrastructure of America began to show. As millions of people lost their jobs, the highest increase in the number of uninsured Americans was subsequently recorded. This high number of uninsured people is a direct consequence of healthcare being employer-sponsored. Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “Medicare For All would have strengthened the response to the pandemic…30 percent of COVID-19 deaths were related to a lack of insurance.”

While gains were made in the past decade in regards to gender equality in the workplace, Congresswoman Jayapal notes that “as soon as the pandemic hit, it was the women who went back to taking care of [their] families.” Dr. İpek İlkkaracan explains that this is because “the nature of women’s employment is often determined by their care responsibilities…unpaid care work is often articulated as one of the most significant barriers to labor force participation.” This notion was reflected in jobs reports—in December of 2020, women accounted for 100 percent of job loss, and within that, 154,000 Black women exited the workforce.

In its current state, the care economy produces a pattern of inequality that disproportionately affects women of color and migrant women. The average caregiver salary is $12.74, and the care work sector is marked by poor working conditions with no adequate social protections and low wages. This is why, as Congresswoman Jayapal notes, the fight for one fair wage is pertinent. “An increase in the minimum wage would give 32 million workers a raise, 60 percent of which are women while 1 in 4 of the women who would benefit from this increase are Black or Latina.”

A Framework for a More Caring Economy:

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan has developed a framework that acknowledges the care economy. This framework, coined as the Purple Economy (a nod to the color representative of many women’s movements), envisions a gender-egalitarian and caring economic system. Dr. İlkkaracan recommends “labor market regulations and investment in care services such as long-term care, early childhood education, education, and healthcare” as policy interventions to start the process of adequately valuing care.

Not only is investment in care important from a humanitarian and ethical perspective, but it is also conducive to economic stability. Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has revealed that investment in care services produces a high employment multiplier: for every dollar invested in care, three times as many jobs are created in the wider economy. This is because the care sector is intertwined with other sectors such as food, transport, and financial services. In the Asia-Pacific region, Dr. İlkkaracan’s research has shown that “up to four trillion dollars could be added to GDP if unpaid care work (75% of which done by women) was valued in market terms.” While this may seem astronomical, the amount of unpaid work completed globally in one day equates to 16.4 billion hours—which translates to two billion full-time jobs. Dr. İlkkaracan’s recent research also reveals that a “3.5-4% commitment of GDP to investment in care services would create 120 million additional jobs and have a large impact on poverty alleviation.”

To watch the full conversation and learn more about the Purple Economy, see below.

Dr. İpek İlkkaracan is a CWE-GAM researcher a part of the Rethinking Macroeconomics and Gender Aware Applied Economics Working Groups.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Gender-Equal Economy, Policy, Rethinking Macroeconomics, U.S.

Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective

Below is an excerpt from a recent piece “Systemic Resilience and Carework: An Asia-Pacific Perspective” by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group. This article was published by Migrants and Systemic Resilience: A Global COVID19 Research and Policy Hub (Mig-Res-Hub).

In this think-piece I consider how we can build a resilient systemic response to the COVID-19 pandemic and future crises. I focus on systemic resilience in relation to carework and global migration of careworkers, and I approach this from an Asia-Pacific perspective. One of the fault lines exposed by the COVID-19 is the vulnerability of the existing care, carework and migration infrastructure to exogenous shocks. Asia-Pacific is an important site to examine because it is one of the major sites of global care migration, both as sender and receiver of migrant careworkers. This think-piece draws on the research from our global partnership project based at the University of Toronto, which looks at the dynamics of careworker migration in Asia-Pacific and the interconnections between social and economic forces and policies in shaping those dynamics from both sending and receiving country perspectives. The next section briefly outlines the pandemic’s impacts on carework and care migration in Asia-Pacific. I then discuss how we might achieve systemic resilience in global care migration by first emphasizing how our care systems are interlocked with the global migration of careworkers (what I call a global care interlock), and second, how we might achieve systemic resilience. Understanding the global care interlock is an important prerequisite to systemic resilience because it allows us to see carework and migration of careworkers as a part of a larger global infrastructure or ecosystem that has been, consciously or unconsciously, built, managed and sustained by multiple actors in different parts of the globe.

Read the entire article here.

This blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing research for the Understanding and Measuring Care research group.

- Published in Asia-Pacific, Child Care, COVID 19, Elder Care, Migrant Care Workers, Understanding and Measuring Care

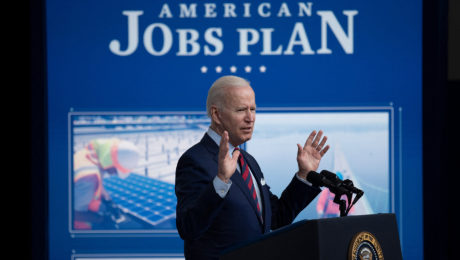

Biden’s American Jobs Plan Could Be Monumental for the Care Economy in the U.S.

Last month, the Biden administration revealed the details of the $2 trillion American Jobs Plan.

The plan recognizes that investing in the care economy, as with investments in traditional infrastructure, can lift incomes, unleash productivity, and pave the path towards a more equitable economic recovery and growth.

Addressing the care crisis

Built into the plan is a pledge to “solidify the infrastructure of our care economy by creating jobs and raising wages and benefits for essential home care workers.” The plan calls for Congress to invest $400 billion towards expanding access to quality, affordable home- or community-based care for aging relatives and people with disabilities. These investments will help Americans to obtain the long-term services and support they need, while creating new jobs and offering care workers a long-overdue raise, stronger benefits, and an opportunity to organize or join a union and collectively bargain. Research has shown that increasing the pay of care workers leads to better quality care overall. Through creating well-paying care jobs with benefits and o collectively bargaining rights, as well as building state infrastructure, the plan aims to improve both the quality of job for care workers and the quality of service for care recipients.

Lack of access to childcare makes it harder for parents, especially mothers, to fully participate in the workforce, hurting families and hindering U.S. growth and competitiveness. In areas with the greatest shortage of child care slots, women’s labor force participation is about three percentage points less than in areas with a high capacity of child care slots. The pandemic has severely exacerbated this problem with more than 1 in 4 facilities still remaining closed as of December 2020. President Biden is calling on Congress to provide $25 billion to help upgrade child care facilities and increase the supply of child care in areas that need it most. These funds are to be provided through a Child Care Growth and Innovation Fund for states to build a supply of infant and toddler care in high-need areas. Also included in this $25 billion is a call for expanded tax credits to incentivize businesses to provide care facilities at their establishments. This will grant accessible, high quality care and learning environments for children of employees. This particular part of the plan is structured so that employers will receive 50 percent of the first $1 million of construction costs per facility.

Investment in care is investment in infrastructure

As Cecelia Rouse, Chair of the Economic Advisors for the Biden administration, recently indicated during a recent press conference, we need to “upgrade our definition of infrastructure” to include the care economy. Rouse defended the Biden administration’s plan to spend $400 billion of the infrastructure plan’s budget on the care economy, defining it as a legitimate infrastructure investment and a key component to addressing economic inequities in the U.S. The care economy is critical to U.S. economic activity, and its absence would greatly hinder economic productivity. The inclusion of care work and the care economy in the American Jobs Plan is a critical first step in mending a critically broken care infrastructure in the U.S.

Still, it is only the first step. The U.S. is the only industrialized nation that fails to provide national paid family leave and medical leave programs, and where hundreds of thousand sit on waiting lists for desperately needed home care. LeadingAge, which represents service providers in the sector, estimates that half of all Americans will need long-term services and support after turning 65, and that by 2040, a quarter of the U.S. population will be 65 or older. In addition to the President’s proposal for the care economy, we also need investments to finally put America on a path to universal childcare and early learning, national paid family and medical leave and paid sick days for all workers. The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed both the importance of care work and the vulnerabilities of our care infrastructure. At the same time, it has also created an opportunity for us to rethink the value of care and care work, opening ways for us to rebuild a more resilient care infrastructure and a more inclusive economy.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Economic Recovery, Policy, U.S.

What is the Care Economy and Why Should We Care?

In our project, we aim to promote and advocate for gender and socioeconomic equalities. We do this by working to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes and by showing and properly valuing social and economic contributions of caregivers; and integrating care into macroeconomic policy making toolkits.

In this era of demographic shifts, economic change and chronic underinvestment in care provisioning, innovative policy solutions are desperately needed, now more than ever. Sustainable and inclusive development requires gender-sensitive policy tools that integrate new understandings of care work and its connections with labor market supply and economic and welfare outcomes.

The Care Work and the Economy Project, currently based at the Economics Department of American University and co-led by Maria S. Floro and Elizabeth King, includes more than 30 scholars around the globe, working closely together to provide policy makers, scholars, researchers and advocacy groups with gender-aware data, empirical evidence and analytical tools needed to promote creative macroeconomic and social policy solutions. In the next phase of the project, Care Economies in Context, we will be scaling up our project to include 8 different countries, in 4 global regions. I will be leading this next phase of the project, which will be based at the University of Toronto.

I define Care work is defined broadly as work and relationships that are necessary for the health, welfare, maintenance and protection of all people – young and old, able bodied, disabled, and frail. This definition may seem broad – but care– at its core is a very basic human need and a necessity. Whether we know it or now, we all participate in providing care work – paid or unpaid, and in receiving care every day.

By care economy, I am referring to the sector of economy that is responsible for the provision of care and services that contribute to the nurturing and reproduction of current and future populations. More specifically, it involves child care, elder care, education, healthcare, and personal social and domestic services that are provided in both paid and unpaid forms and within formal and informal sectors.

Care work is important because it is important work that sustains life. It is also important now in particular because it is one of the fastest expanding economic sectors and a major driver of employment growth and economic development around the world. For example, across the OCED, the service sector economy now accounts for over 70 percent of total employment and GDP. In lower- and middle-income countries, it is estimated to comprise nearly 60 percent of GDP. Within the service sector economy, care services is one of the fastest growing subsectors.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that the global employment in care jobs is expected to grow from 206 million to 358 million by 2030 simply based on sociodemographic changes. The figure will be even more dramatic to 475 million if governments invest resources to meet the UN sustainable development goal targets on education, health, long-term care and gender equality.

In Canada, the service sector already makes up for 75 percent of employment and 78 percent of GDP. Within this sector, healthcare, social assistance and education services are key drivers of economic and employment growth. In the U.S., healthcare is already the largest employer, larger than steel and auto industries put together. In short, our current and future economy is and will be increasing dominated by care services and care work.

However, at the same time, much of the care work continues to be performed for no pay, by families and friends, at home and in communities. This unpaid care work is not including in in our national GDP because GDP only takes into account work that is done for pay in the formal market. Therefore, if we only look at the GDP as a measure of the economy and economy growth, we miss a huge segment of the economy and economic activities. As the pandemic has shown, without both paid or unpaid care work, our economy will not be able to function effectively, nor would it be able to sustain itself.

What we are trying to do in our project is to make the care economy clearer and more visible by measuring and mapping out the size and shape of the economy, and to develop macroeconomic models that would help policymakers and civil society actors to develop better policies and better strategies to ensure more sustainable and equality inducing economic growth.

Listen to the full talk “The Care Work and the Economy Project” to learn about what the care economy is and why we should know more about it, particularly now.

The blog was authored by Ito Peng, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care research cluster

- Published in Canada, Child Care, Economic Modeling, Elder Care, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, OECD

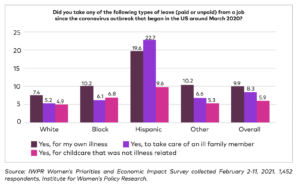

Women and the Pandemic in the U.S.

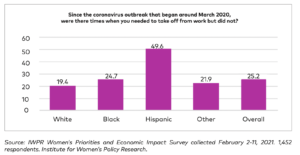

Institute for Women’s Policy Research released a report in February 2021”IWPR Women’s Priorities and Economic Impact Survey” outlining a recent poll of 1452 women in the U.S. The findings are backdropped by the experience of women throughout the pandemic and resulting economic turndown, in which 2.35 million women have left the workforce since February 2020.

Some of the key findings from this survey are:

- 1 in 4 women report that they are worse off financially than one year ago

- Nearly half of all women are worried about the financial situation of their families

- 1 in 4 women report having needed to take time work off but did not do so

- 40% of women reported care demands stopped them from working or forced them to reduce hours

- 69% of women support paid sick time to have a child, recover from a serious health condition, or care for a family member

- 20% of women with children want the Biden administration to address childcare and education in the first 100 days

In terms of women experiencing reduced paid work as a result care demands, this has also been pointed to within recent working papers put out by the

The impact of care demands on women’s paid work is explored in a number of Care Work and the Economy Working Paper Series. For instance in two recent papers, “Gender Wage Equality and Investments in Care: Modeling Equity and Production” and “Parental Caregiving and Household Dynamics”.

Education and childcare were listed among the top priorities for the Biden administration to address within the first 100 days among survey participants. This is largely because women’s ability to reenter the workforce largely depends upon safe reopening of schools and childcare facilities.

Latinas have been hit particularly hard according to this survey, reporting the highest levels of taking leave from jobs in order to provide care. However, across all ethnicities, 69 percent of women expressed strong support for paid sick leave and the ability to take time away from work to provide care or recover from illness.

The Unites States remains the only high-income country in in the world that fails to provide guaranteed paid sick or family leave for workers. The Family Medical Leave Act, which provides unpaid job protection, and only for about 56 percent of workers. The Families First Coronavirus Relief Act has provided access to paid leave as a result of the pandemic but falls short in the fact that more than 100 million workers are excluded from this because they are caregivers.

In order to address the many issues identified throughout this survey, there is strong need for targeted programs and policy solutions that will aid a gender equitable recovery. This recovery should not only address immediate short term needs but include long term strategies that will create more resilient systems that recognize the contributions of women to the workforce, society and family structure.

IWRP specific recommendations for the short term are:

- Continuing economic impact payments

- Expanding access to affordable healthcare

- Providing paid sick and medical leave

- Raising the federal minimum wage

- Building a new childcare infrastructure

Equitable economic recovery necessitates a national care system that meets the needs of all families, raises wages and provides quality childcare, treating it as a public good instead of a private obligation.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

- Published in Child Care, Gender Inequalities, Policy, Policy Briefs & Reports, U.S.

Engendering the Macroeconomy: Current Efforts and Future Directions

On International Women’s Day earlier this month, the Whitaker Institute hosted a webinar titled “Engendering the Macroeconomy: Current Efforts and Future Directions” featuring Dr. Maria S. Floro, Principal Investigator of the Care Work and the Economy Project (CWE) and CWE contributing researcher Dr. Srinivasan Raghavendra. Dr. Raghavendra also serves as Co-PI of DFID funded research on “Economic and Social Costs of Violence Against Women and Girls.” This session was hosted by Dr Nata Duvvury, co-leader of the Gender and Public Policy cluster at the Whitaker Institute.

The webinar focused on exploring what engendering the macroeconomy entails, current efforts, and future directions. The discussion provides insight into ways to bring gender dimensions into macroeconomics by incorporating unpaid and paid care of children, the sick, disabled and the elderly into existing macroeconomic models, the interdependency between the market economy and the care economy, and how gender blindness of macroeconomic models are reflected through every crisis.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant.

- Published in Economic Recovery, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Gender-Equal Economy, Macroeconomics

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part II

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” The discussion describes the interconnections between the crisis of care, the deepening ecological crisis and growth and accumulation processes.

There are many common threads with the climate and ecological crisis and the care crisis. Significantly, the idea that economic growth is overall beneficial. The type of economic growth generally pursued worldwide has not only increased stresses put upon the earth’s resource base but also on care labor capacity, which is similarly but wrongly perceived to be of infinite supply. Moreover, arguments that equate economic growth with overall improvement fail to recognize the distributional element of rising income inequality, which is far more nuanced. In fact, among countries that are higher income, gains from economic growth within those nations do not trickle down to everyone. When looking at care, the widening income equality gaps has shifted distribution of care givers across social classes and national boundaries. As a result, the quality and adequacy of care within a single nation can be very different, which exacerbates differences in social reproduction.

At the same time, income inequality has created a solution for the care needs of those that have the means to hire care for children and elderly, because care workers in those sectors are often paid low wages. But for the working poor, hiring care work help is inaccessible due to financial constraints, therefore they rely on their kinship networks to help provide this care. Furthermore, much of the care work burden still falls on women even as they enter to labor force. Economics and social policy in many parts of the world continue to neglect the heavy work burden put upon women and the necessity to balance household care activities and market work. What can also be observed is a global care supply chain, with the migration of women and girls to urban areas to provide care for wealthier families. Care itself is becoming one of the drivers of income inequality.

The economy is not all about material production; it is really about human vision and social provisions. However, an illusion has been created that unpaid care work is a natural resource that serves as an input for market production to promote GDP growth. However, this idea does not take into account that the wellbeing of people, especially the elderly, the sick and children should be an end in and of itself, to achieve sustainable growth. There is much work to be done to address these issues. To begin, economists must envision long term horizons that look forward to future generations while also taking into account the interdependence of life and moral responsibility. They must also integrate care and environmental consequences into our economic policy tools. Overall a new economic paradigm that includes green ecology and feminist economic concerns is needed.

Link to Part 1 of this blog here.

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part I

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” This discussion delves into the foundation of project itself, its context, the analytical tools utilized in the research, as well as the external factors that have served as the catalyst for the work being done.

The Care Work and the Economy Project was developed after a group of feminist economists observed that in the effort to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes, as laid out within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, there were aspects of care work that needed to be addressed. The project includes 35 scholars from all around the world that are working to develop innovative analytical tools. The research has been applying and testing these tools in South Korea, a country that quickly industrialized in the 70s and 80s and therefore witnessed a very rapid demographic change in fertility and life expectancy.

The care economy, which is inclusive of caring for those that cannot care for themselves, underpins the production of all economies within society. This begins with the fact that if people stopped having children, which require care, then the economy would come to a halt due to lack of labor force. Generally, care work has a tendency to be undermined through a lack of gender awareness in macroeconomic modeling, which does not address care needs in any adequate manner. This aspect is also neglected within the policy making discourse, with the current economic paradigm failing to take into account the necessity for care work to achieve economic growth.

Economic models that display growth also fail to take into consideration social elements, making the assumptions that, for example, children will be cared for despite the lack of social investment into care. However, with care work there comes social, political and economic significance. The Care Work and the Economy project is working to demonstrate what a care focused macroeconomic model can reveal through the implementation of the analytic tools being developed and implemented through the research.

The absence of the care economy within macroeconomic models is in large part due to it being “invisible” since the work often unpaid. This has led to the neglect of care needs despite unpaid care work providing indispensable services in terms of economic activity and growth. The result is an emerging care crisis that has manifested itself in terms of uncared for elderly, sick and children. Furthermore, the crisis has provoked a form of silent protest against long unpaid work hours performed by women, leading to a decline in marriage and fertility rates. This in turn has resulted in a reproduction crisis.

The Care Work and the Economy project researchers are developing and using innovative analytical tools to bring care to the forefront, along with a deeper understanding of the nature of care work, while illustrating the intersectionality between care provisioning, economic growth and distribution. Although these analytical modeling tools are currently being applied in South Korea, the project believes they can be adopted and implemented into other countries as long as the provision of care is taken into context of those countries. The project research shows that governments have an important role and duty to invest in care provisions as well as comprehensive national care plans. One of the key findings is that it is important to take into account demographic change and climate change along with economic and structural changes taking place in policy making. This is a tall order but necessary to sustain economies and provide a future for next generation.

Link to Part 2 of this blog here.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant