The Journey of the Care Work and the Economy Project

As the CWE-GAM project is coming to a close, the final activities in the summer of 2021 showcased the groundbreaking research that was conducted over the past year and prompted valuable conversations between researchers, activists, donors, and more. Professor Maria Floro, the Co-Principal Investigator of the project, launched the Concluding Annual Meeting with opening remarks that summarized the timeline, features, and accomplishments of the project.

The Care Work and the Economy project began in 2017 and was built around the fundamental research goals of highlighting the impact of care work, socially and economically, and emphasizing the need for policy agendas to address the care economy. The project’s working groups consisted of innovative, interdisciplinary researchers who brought expertise and toolkits from a variety of schools of thought including heterodox, feminist, political economy, structural, and mainstream economics. The project used South Korea as a case study for the care economy which was made possible by a strong partnership with Korean researchers and the collection of unique time use and household survey data by the Center for Transnational Migration and Social Inclusion at Seoul National University.

Over the course of the past four years, the project has hosted two annual meetings, two conferences with Korean advocacy groups, and virtual workshops during the Covid pandemic. Additionally, the project produced two policy tools for the Korean government, 33 working papers showcased on the project website, and special issues in Feminist Economics and World Development. The final two activities conducted by the project were the Seoul Policy Dialogue in early June and a virtual intensive course on Gender-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling for Policy Analysis in partnership with the Levy Institute at Bard College.

To watch the full Opening Remarks of Professor Maria Floro from the Concluding Annual Meeting, see below.

Written by Catherine Falvey, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project and PhD student in Economics at American University

- Published in Conferences, Expert Dialogues & Forums, Maria Floro

Caring For the Future: How Public Spending Makes a Difference

During the first week of June, the Center for Transnational Migration and Social Inclusion at Seoul University and the Care Work and the Economic Project at American University will host a conference to discuss the role of care work and the care economy in a post-pandemic future. National and international scholars will take this opportunity to discuss the role of public spending in gender equality, and its relation to economic growth.

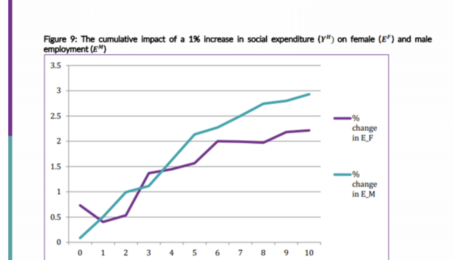

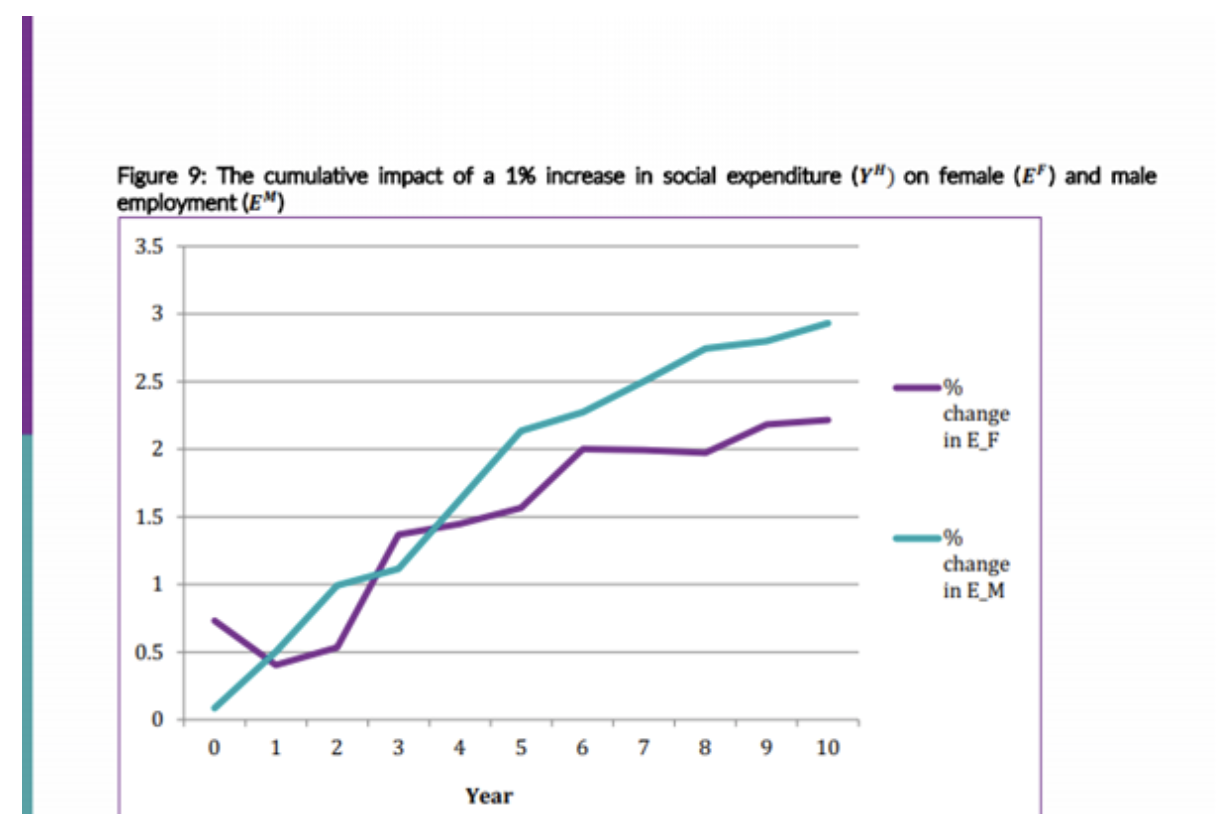

In their paper “The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment: The Case of South Korea”, Oyvat and Onaran (2020) use a feminist post-Kaleckian model to estimate the impact of an increase in the total social infrastructure expenditure, wages, and closing the gender pay gap on output and employment. They find that an increase in South Korea’s public social expenditure has a positive cumulative effect on output, as well as on female and male employment (hours of work) in the non-agricultural sector, both in the short and medium terms (figure below).

(Oyvat and Onaran, 2020, p.29).

Pierre-Richard Agenor and Madina Agenor in “Access to Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation and Economic Growth” (2019) develop a two-period, gender-based overlapping generations model (OLG) with public capital to explore the implication of public infrastructure on women’s time allocation and growth. They find that government provision of infrastructure can induce women to reallocate time away from home production activities and toward market work, as well as have a significant impact on health and education for both men and women, positively affecting their productivity.

Finally, Ignacio Gonzalez, Bong Sun Seo and Maria S. Floro use a macroeconomic overlapping generations model (OLG) to incorporate long-term care and the provision of gender-based unpaid care in their paper “Norms, Gender Wage Gap and Long-Term Care” (2020). They consider the persistence of traditional gender norms as an explanation to the perpetuation of unequal distribution of care work across genders. The unfair division of unpaid care work increases the gender wage gap and creates gender-unequal equilibrium outcomes. They examine how investment in quality care services, care relevant infrastructure, and in encouragement of gender-egalitarian norms can play a role in reducing and redistributing the load of unpaid care work.

This blog was contributed by Carla (Anai) Herrera, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

Sources:

Agenor and Agenor (2019). “Access to infrastructure, women’s time allocation and economic growth” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. DOI: 10.17606/8m8y-mp65

Gonzalez Garcia, Seo, and Floro (2020). “Norms, gender wage gap and long-term care” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/7E2K-1508.

Oyvat, C. and O. Onaran (2020). “ The effect of public social infrastructure and gender equality on output and employment: The case of South Korea “ Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. DOI: 10.17606/fhq4-c294

- Published in Uncategorized

The Cost of Caregiving to Caregivers of South Korea

What are the costs of caregiving?

Conventionally, caregiving is considered a household activity that relates to parents raising their infant and young children and adult children taking care of their older parents. Care is broadly categorized into eldercare and childcare but may also include household chores such as cleaning and cooking. There is a dependency between the caregiver and care-receiver, involving both a financial and time cost to the caregiver.

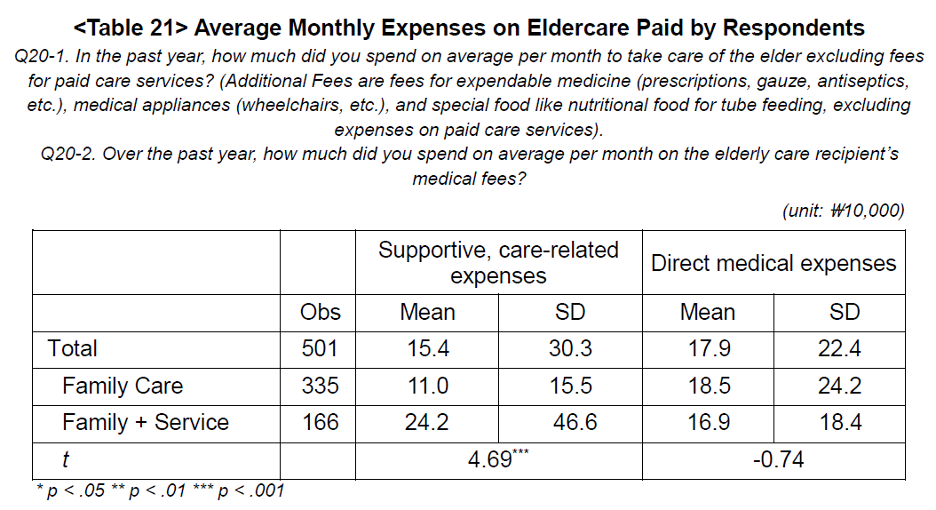

The financial burden of caregiving usually falls on the working age population of an economy. It is the direct cost of caregiving and may include costs to cover basic needs of the dependents such as food, shelter, medical expenses and in some cases, professional supportive care services. Using two nationwide Care Work and Family Surveys on Childcare and Elder care for South Korea, Kang et al (2021) found that on average, a family spends ₩154,000 on supportive care related expenses and ₩179,000 on direct medical expenses. However, a family that hired care services pays ₩132,000 more for supportive care related expenses, than a family that relies only on household unpaid labor. This difference is attributed to higher purchases of expendable medicine and medical appliances (Kang et al. 2021). The higher costs of hired care is offset by a ₩16,000 decrease in direct medical expenses.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

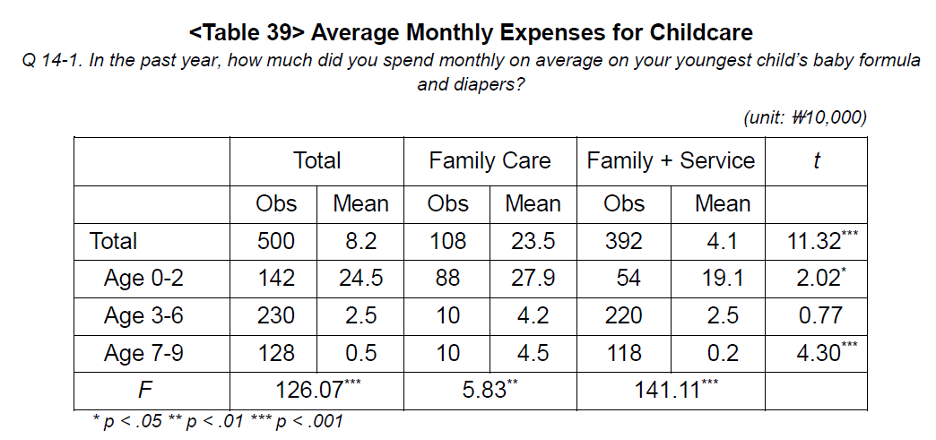

The same study also examined childcare expenses and finds that on average, families spend ₩82,000 on monthly childcare expenses. Here, there are significant cost cutting benefits to hiring paid childcare services. Unlike with eldercare, hiring childcare services decreases monthly childcare expenses for all age brackets. Given the survey question used to measure these expenses, a possible explanation is that service providers supplied these items (baby formula and diapers) and that the payments for such services included these costs.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

In addition, dependents required significant time commitments for labor intensive care activities such as feeding, bathing, and nursing. There is also supervisory care that does not require active caregiving, but is a considerable time commitment, nonetheless. Furthermore, “[t]he still-prevailing belief is that care work is primarily a family duty and responsibility and of little direct relevance to economic development. This neglect ignores the realities that households face: the unequal burden of care within households, the impact on girls and women who bear the brunt of that burden … Unpaid care work is critical, but remains “invisible”” (King, Randolph, Floro, et al. 2020).

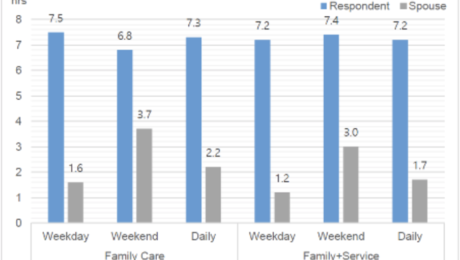

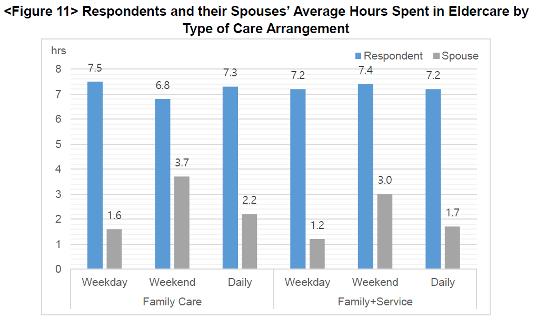

Notes: Respondent in Figure 11 is female.

Source: Kang et. al (2021)

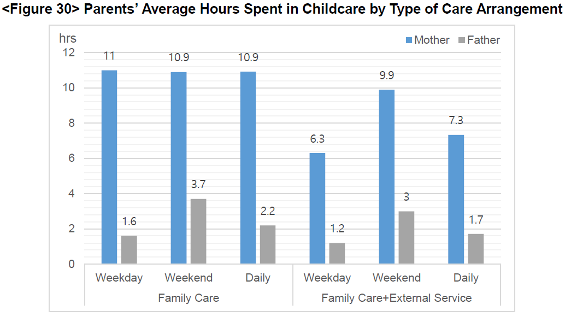

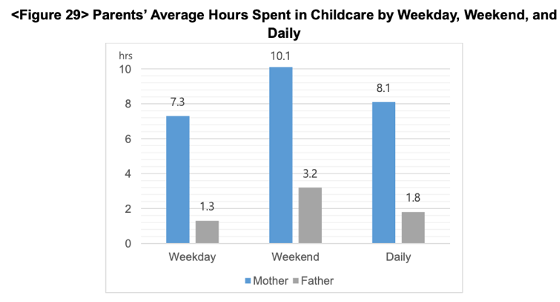

These graphs show the gender disparity in the division of care work within the household. On average, women engage in care activities at least twice as long as men, this applies to eldercare and childcare. The graphs also reveal a tendency of hired care relieving men of care duties more than women.

Finally, these time commitments involved an opportunity cost to the caregivers; forgone time and wages.

Survey used: 2018 Family Survey for Elder Care

Source: Cha and Moon (2020)

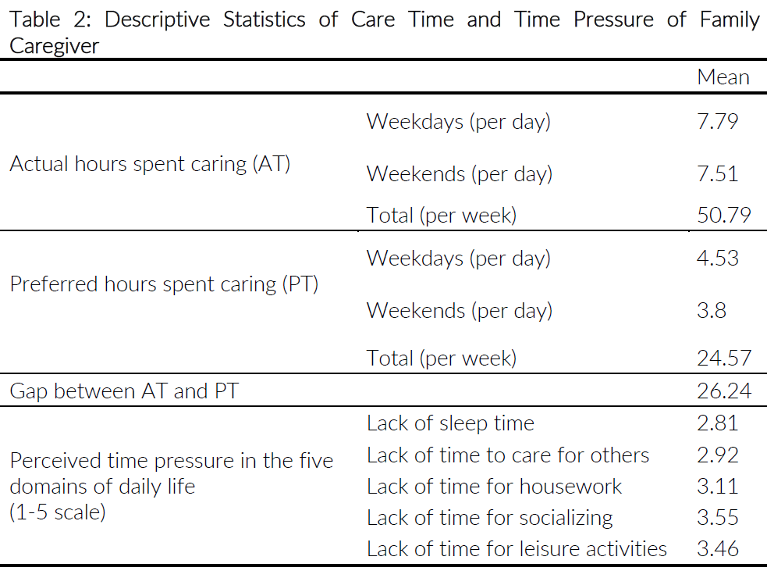

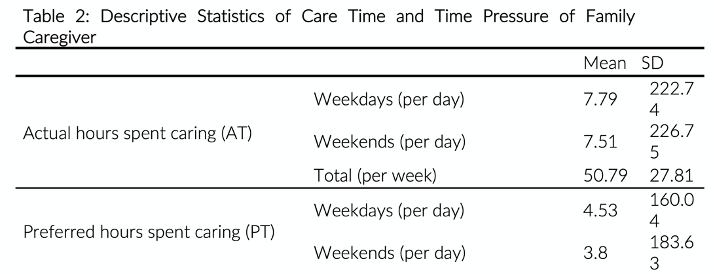

Distinguishing between actual time and preferred time spent in caregiving, Cha and Moon (2020) discovered that on a weekly basis, a household caregiver dedicates a day (26.24 hrs) more than they would prefer to on unpaid care work. The respondents also indicated that there is a lack of time spent in socialization and leisure, which are vital for wellbeing.

Future demand and supply of caregiving.

An aging population, declining fertility rates and a wide gender wage gap implies that the demand for caregiving will continue to exert pressure on South Korean women. “Our estimates clearly illustrate the influence of social norms on the division of labor, the gender allocation of roles and responsibilities, and time use on the potential demand for and supply of caregiving in these countries. They further show that the care burden borne by unpaid household members is quite large relative to the size of the paid labor force, and emphasize that care policies should be a key part of development policy for many countries,” (King, Randolph, Floro, et al. 2020).

This blog was contributed by Praveena Bandara, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha and Moon (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eun, Jun, Cha, and Moon (2021). “Care Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

King, Randolph, Floro, and Suh (2020). “Demographic, Health, and Economic Transitions and the Future Demand for Caregiving.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis (PAGE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/6WYH-SS95.

- Published in Care Infrastructure, Child Care, Paid Care Services

Current Situation of Care Work in South Korea: 2018 Family Survey

The Care Work and the Economy project’s 2018 fieldwork in South Korea helped us learn a great deal about how childcare and eldercare is provisioned, both in the paid and unpaid care sectors, in Korea.

The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys, including two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers and unpaid care providers. The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and recipients.

What We Learned about Family Caregiving in Korea

Although many families use at least one external care service to assist with childcare, 22% of respondents reported that their childcare was done only by family members (Kang et al.). Mothers spent six to seven hours more than fathers taking care of children on average.

(Kang et al.)

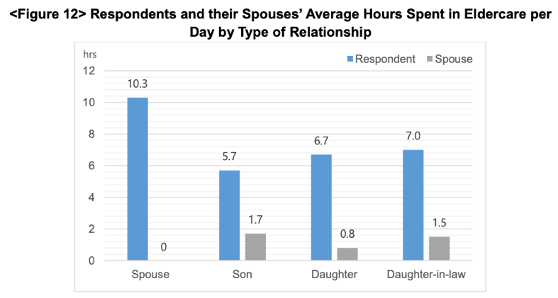

In contrast, 67% of respondents reported that their eldercare was done by family members; the rest reported using external care – usually the national LTC program. The primary caregivers were daughters-in-law (37% of the time), daughters (35%), spouses (15.6%), and sons (11%) (Kang et al.). Figure 12 shows how rather than the elder’s biological children, daughters-in-law provided the most care in terms of time, excepting the elder’s spouse.

(Kang et al.)

The cost of eldercare is shouldered solely by the primary caregiver in many cases (Kang et al., 2021)

Only 20% of family eldercare providers reported receiving regular financial support from other family members, less than 30% reported receiving help on an irregular basis, and only 8% of those over 65 years old were currently receiving LTC insurance program benefits.

Unpaid care provisioning impacts women’s employment.

The surveys showed that “families in which mothers were the sole caregiver for the child had the highest proportion of unemployed mothers, whereas families that received help with childcare from grandparents or paid care service had the highest proportion of employed mothers. With respect to both types of care arrangements, it was mostly daughters and daughters-in-law serving as primary caregiver, almost 70% of whom were unemployed.” (Kang et al.).

When asked about their preferred hours spent caring, eldercare workers reported a considerably lower number of hours on average than the actual hours they spent caring (see Table 2).

(Cha and Moon,2020)

Studies in the CWE-GAM Project stress concerns about the “quality of the caregiver’s life and the care they provide as well as the quality of life of the care recipient. Especially given that women are typically taking on the role of caregiver, this issue cannot be detached from concerns regarding women’s labor, women’s quality of life, and gender equality in Korea.”

Current Situation in Korea – Government Implications:

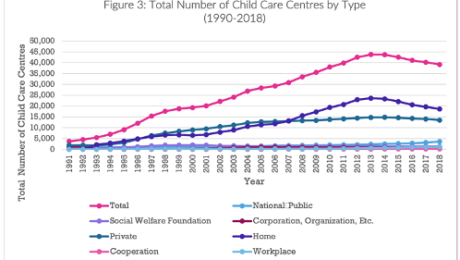

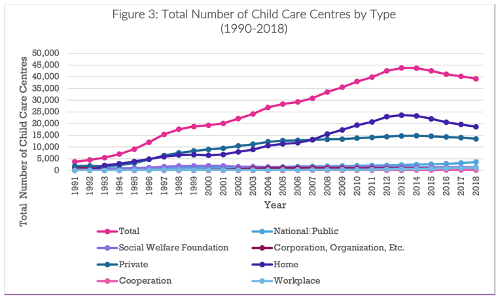

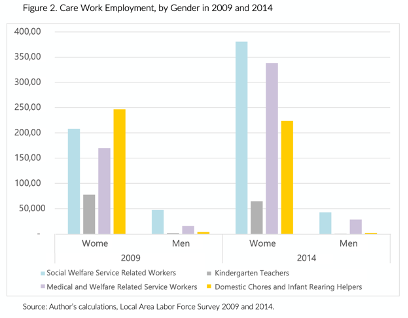

Korea currently “ranks amongst the top 10 OECD countries in terms of public investment in childcare and education” and implemented a mandatory universal LTCI program in 2008 (Peng et al 2021). Figure 2 and 3 show the evolution of child care and care work over time.

(Peng et al. 2021)

(Suh 2020)

Studies report that despite the social care expansion, “childcare and long-term care sectors are heavily dominated by women, and these care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and precariously employed. Care work is also accorded low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress” (Peng et al. 2021; Suh 2020).

Suh (2020) finds that “public investment in quality care services tends to improve the working conditions of care workers (thereby benefiting care recipients), and unregulated private provision tends to worsen them.”

This suggests that “the government and public sector should drive the effort to meet the multi-faceted challenges posed by the growing demand for care work” (Suh 2020).

“The Korean government […] continues to see care work as an extension of women’s unpaid care work and social care expenditure as something that need to be tightly controlled. A better understanding on the part of policymakers about the importance of care and the role of care work and the care economy in generating employment and positive economic growth and supporting a healthy productive economy is therefore necessary.” (Peng et al.)

This blog was contributed by Aina Krupinski Puig, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha, Seung-Eun, and Hyuna Moon. (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family

Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eunhye, Ki-Soo Eun, Jiweon Jun, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “Care

Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

Peng, Ito, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “An Overview of Care Policies and the

Status of Care Workers in South Korea.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/EHN0-R646.

Suh, Joo Yeoun. (2020). “Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea.” Care Work and the

Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/bpdf-v686.

- Published in Child Care, Elder Care, Paid Care Services, Policy, South Korea, Unpaid Care Work

Fellows Reflect on Intensive Course in Gender-Aware Macro Modeling

Last month, the Care Work and the Economy project partnered with the Levy Economics Institute at Bard College to host a three-week Intensive Course in Gender-Sensitive Macroeconomic Modelling taught in three time zones. The course aimed to engage our internationally diverse pool of Fellows to enhance capacity building in research and teaching of gender-sensitive economic analysis, focusing on care and macroeconomic policy aspects.

The course was built on four pillars:

1. Understanding and measuring the care economy

2. Adapting social accounting matrices to account for paid and unpaid care activities.

3. The use of information from time-use surveys on unpaid care activities with other relevant sources and information such as national income accounts, labor force surveys, and household or special surveys

4. Performing policy-relevant economic analyses that take systematic account of the interlinkages between care, macroeconomic processes, and distribution.

With 72 Fellows from 22 countries, including Colombia, Ghana, Mexico, Mongolia (to name a few), discussions around course material were perspective-rich and interdisciplinary. Reflecting on the course, many Fellows expressed the desire to integrate the teachings of the intensive course into their research agendas or current positions:

“I am delighted [to be a part of] a fantastic cohort and faculty who want to, and actually do, think critically about [macroeconomic] modelling in a gender-aware or feminist context…I am excited about the possibility of applying what I have learned to Cuban and Latin American contexts, [and] I would like to delve deeper into the Levy Micro-Macro model to analyze gender differences [in] the Ecuadorian context using time-use data.” — Anamary Maqueira Linares, Ph.D. student at University of Massachusetts, Amherst from Ecuador

“Inspired by Professor Folbre’s [lecture], I would like to conduct research using updated time-use surveys (such as the Mexican case)…I would like to explore the differences between time-use patterns in rural areas versus urban ones in Mexico and compare data from 2014 to the recent time-use survey in 2019. I am also organizing a workshop with the Mexican Statistics Agency [to explore] how the Mexican database was built (contrasted with other countries’ surveys) and promote its use among Mexican graduate students and policymakers.” — Dulce Guevara Lopez, consultant at the Mexican Centre for Innovation in Solar Energy

“It was interesting to learn how care and social reproduction interact with gender inequality in the labour market to determine economic growth/development. I think that [this would be] a good research perspective in the African context to see how household commodities and care-time interact with the gender segmented labour market to determine economic growth.” — Dr. Mamaye Thiongane, research associate at the Regional Consortium for Research in Generational Economy (CREG) and lecturer in economics at the Public Economics Laboratory (LEP)

“The discussions around the care diamond gave me a framework to think through the situation of community health workers in India. I plan to apply the Levy model and the care dependency ratio to the time-use survey for India. The course also helped me gather feminist insights to incorporate into the macro course that I teach at university.” — Dr. Anjana Thampi, assistant professor of economics at O. P. Jindal Global University, India

“The course was a fantastic deep-dive into the theory and practice of [macroeconomic] modelling for care, and sparked new ideas for my Ph.D. research. At a time when distances feel huge, the conversations and connections with lecturers and colleagues created a sense of closeness; something I will treasure this summer.” — Maria Sandoval Guzman, Ph.D. candidate in Economics at Curtin University in Australia, and scholar at the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre and the Women in Social Economic Research Cluster

This course has strengthened the network of researchers around the world dedicated to gender equality and proper care valuation; thank you to all Fellows, Instructors, and Facilitators for their contributions. To learn more about the course, instructors, and Fellows, click here.

This blog was written by Lucie Prewitt, research and communications assistant for the Care Work and the Economy Project.

Investing in Quality Care has Positive Macroeconomic Effects

Recent research by Lenore Palladino and Chirag Lala of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts Amherst, examines the effects of critical public investment in childcare, home health care, and paid family and medical leave (PFML) for the U.S. workforce, as proposed by the American Jobs Plan and the American Family Plan by the Biden-Harris Administration.

The authors find that investing in childcare and home health care workforce has positive macroeconomic effects, and the care workforce spends its own money on goods and services through the rest of the economy. They also find that PFML positively boosts the economy, as workers spend the wage replacement income they earn.

The authors model the effects of a $42.5 billion annual investment in childcare and a $40 billion investment in home health care with a minimum wage of $15 an hour and find that the proposed investment can create 564,000 additional jobs throughout the economy, and results in an increase in labor income of $82 billion annually. They find that universal paid family and medical leave, as proposed by the American Families Plan, would increase household income nationally by $28.5 billion, of which $19 billion would be wage replacement directly from the paid leave program, and $9.4 billion would be income earned by workers throughout the economy as people receiving wage replacement spend money on goods and services. This means that for every dollar spent on wage replacement as part of the paid leave program, other workers would earn an additional $.50.

RESEARCH BRIEF: The Economic Effects of Investing in Quality Care Jobs and Paid Family and Medical Leave

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, program manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project.

- Published in Care Infrastructure, Child Care, Elder Care, elderly care, Gender-Equal Economy, Healthcare, Macroeconomics, Policy

Climate Change and COVID-19: Why Gender Matters

This article was originally published in the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs on July 9, 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the important intersections of climate change, food security, migration, and socio-economic inequalities. An understanding of the gendered dimensions of these interconnected global concerns is crucial for developing a post-COVID recovery plan that ensures a more equal world and bolsters its resilience.

In many ways, the year 2020 spotlighted the compounding issues societies must reckon with, including climate change, COVID-19, and sustained inequality. Today, we are witnessing the drastic consequences of climate destabilization resulting largely from human actions: frequent heat waves, intense flooding and droughts, water crises, increased biodiversity loss, reduced agricultural productivity, and faster disease transmissions. Many of these underlying causes of climate change also increase the risk of future pandemics. For example, deforestation leading to loss of animal habitat forces animals to migrate and brings them into closer contact with other animals or people, increasing the likelihood of zoonotic transmission.

The effects of climate change are being felt throughout the world; its worst impacts are particularly damaging in poorer regions, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Asia. Severe and prolonged droughts have already affected the Sahel and most of East Africa. Meanwhile, severe storms and flooding are causing extensive damage across the world, and climate change-related food insecurity has resulted in thousands of deaths. Climate change has also intensified water scarcity, reaching critical levels in seventeen countries. Major rivers no longer reach the ocean, while reservoirs and lakes dry up and underground water aquifers are depleted. As climate change continues, drier areas will only be more prone to drought and humid areas more prone to flooding. As food, water, and other resources become increasingly strained, fierce competition over scarce natural resources is likely to escalate. In fact, natural disasters and climate-related conflicts have already dislocated millions of people. In 2017 alone, the UNHCR estimates about 30.6 million new displacements associated with conflicts across 143 countries and territories.

Making Gender Visible in Climate Change Issues

It is fundamental to note that these aforementioned issues are gendered. Gender disparities in access to resources such as land, credit, and extension training have put many women at greater risk with regards to maintaining their livelihoods and accessing food and water. Climate change not only reflects pre-existing gender inequalities, but it also reinforces them. The pivotal role of women in food security is well-documented. Recent estimates for Africa indicate that women provide 40 percent of labor in crop agriculture while at the same time providing labor in small livestock, poultry, and other food production-related activities. Many are income earners, serving as breadwinners in female-headed households while performing most of the household and family care work. However, gender inequalities in the ownership and control of household assets, gender discrimination in labor markets, and rising work burdens due to male out-migration undermine women’s income generating capabilities. Much of women’s work in food production and food access remain statistically invisible because conventional economic indicators fail to capture the significance of their contributions—contributions that are also overlooked in policymaking.

The gendered consequences of climate change include effects on migration flows. Migration has diversifies livelihoods and serves as an important coping mechanism through the promise of remittances or a better life. Internal and international migrations involve individuals and families seeking protection as refugees from the violence in their communities and states and those whose livelihoods are threatened by natural or man-made factors such as natural disasters, economic crises, or political instability. More recently, the increased frequency of extreme weather events and high temperatures have led to climate-induced migration flows exemplified by the influx of climate refugees seeking entrance into the United States in response to hurricanes, and rural-urban migration in Vietnam in response to typhoons.

The ability of households and their members to relocate varies depending on their resources and their vulnerability to the risk of falling further into poverty. Both the gendered dimension of migration and the climate shock impact on migration decisions are nuanced. Migration can challenge certain social expectations and cultural norms. Household care responsibilities and gender roles may restrain women from migrating. In the case of increased conflicts over natural resources, for instance, women are less able to flee than men as they are often responsible for taking care of the children. In Indonesia, climate shocks have promoted more migration among men. Similarly, male migration in Ethiopia and Nigeria has increased with drought and weather variability, while women are forced to stay put due to financial constraints. On the other hand, increasing demands for care workers in countries with high female labor force participation and aging populations provides employment opportunities for women, fueling international migration flows. In 2019 alone 48 percent of the 272 million (3.5 percent of the world’s population) international immigrants were female.

Gender and the COVID-19 Pandemic

The trends in climate-induced problems have foreshadowed the severity of the crises induced by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has affected all aspects of everyday life and work and has placed a heavy toll on families, communities, and economies. It threatens food security for tens of millions of people. The COVID-19 crisis, like the climate crisis, is causing disparate impacts across nations and social groups. It poses a much greater risk to elderly persons and those with underlying risk factors. Countries with fewer economic resources and weak social and health infrastructure are at a higher risk, not only in the short term but also in the longer term. Politically underrepresented groups suffer the most from lockdowns, rising unemployment, and unexpected medical costs, exacerbating existing economic inequalities.

More importantly, the COVID-19 crisis also unravels and further amplifies gender inequalities. As millions of people lose their jobs or become forced to work from home, many, especially mothers, are compelled to simultaneously juggle work and childcare responsibilities. Unpaid care work has increased not only with children out of school but also with the heightened care needs of the elderly and the sick, especially when health services are either inaccessible or overwhelmed. Ultimately, many women are earning less, saving less, working precarious or insecure jobs, or living close to poverty.

Gender-based violence is rapidly increasing as well. Many women are being forced to “lock down” at home with their abusers at a time when support services for survivors are being disrupted or made inaccessible. In Peru, the imposition of lockdowns has led to a 48 percent increase in phone calls to the helpline for domestic violence.

The COVID-19 pandemic also exposes the precarious employment conditions of many “essential workers” whose jobs increase their risks of infection and are often employed on temporary contracts. Migrants are among the key workers who deliver essential services; they play a critical role in essential sectors in many high-income countries working as crop pickers, food processors, care assistants, and cleaners in hospitals. These migrant workers help facilitate systemic resilience to threats, but their own vulnerabilities go unaddressed.

Conclusions

We cannot afford to ignore the particular vulnerability of women when analyzing the effects of climate change on food security and migration, and we cannot ignore their susceptibility to food insecurity and violence. As governments and policymakers grapple with the challenge of bolstering resilience, they will need to think beyond the effects of these shocks on markets and to pay more attention to the heightened social and economic inequalities. Such an objective requires a comprehensive, gendered approach that considers women’s roles in the provision of essential goods and services and the differentiated impacts of climate change.

Fiscal stimulus packages and emergency measures have been put in place by many countries to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19, but it is crucial that these responses as well as post-COVID recovery plans put women and girls’ interests and needs, rights, and protection at their center. Such responses and plans should include expanded public investment in the care delivery system, from childcare to healthcare to eldercare, which the COVID-19 crisis has disrupted. There is also a need for gender-sensitive analyses of the effects of economic, social, and migration policies along with the development of legal frameworks that effectively address domestic violence. Meaningful participation of women in policy discourse and dialogue addressing climate change is vital as they are disproportionately vulnerable.

Governments should also undertake and support the collection of sex-disaggregated data on various economic, social, and climate-change related indicators as the lack of data is sometimes used as an excuse not to implement gender-responsive policies. As UN Women has stated, “it is not just about rectifying long-standing inequalities but also about building a more just and resilient world.”

This article was written by the CWE-GAM Project’s Principal Investigator Maria S. Floro and was originally published in the Georgetown Journal for International Affairs on July 9, 2021.

- Published in COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics, Gender Inequalities, Gender-Equal Economy, Maria Floro, Policy

“Girly Issues” Are Now the Country’s Issues

Dr. Nancy Folbre, an Advisor and Researcher of the CWE-GAM project and a groundbreaking feminist economist was among the first to sound the alarm about the care crisis. Dr. Folbre’s work on the care sector, once considered “just girly issues” by fellow economists, are now recognized as issues belonging to the U.S.. Previously the recipient of the 1998 MacArthur “genius” grant, Dr. Folbre’s research has journeyed from “fringe idea to more mainstream policy.”

Once cast aside in policy discussions, the care crisis is finally getting the spotlight it deserves after the pandemic forced many schools and child-care centers to close, leaving “ten million mothers of school-age children out of the workforce.” The pandemic is forcing policymakers to finally face the cracks in America’s care infrastructure that Dr. Folbre and other experts have long pointed out— “a system where working parents do not have reliable, affordable child care is one where they cannot reliably build a career.”

To learn more about Dr. Folbre’s work on care, visit her blog Care Talk and read her recent book The Rise and Decline of Patriarchal Systems.

This blog was authored by Lucie Prewitt, a research assistant for the CWE-GAM project.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Economic Recovery, Feminist Economics