Frontline Care Workers in the U.S.

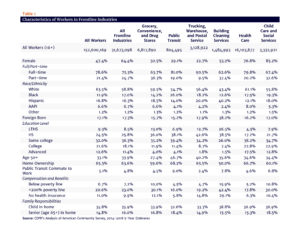

A recent report on Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in U.S. Frontline Industries by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) looks at six broad industries, employing grocery store clerks, warehouse workers, bus drivers, and care workers – including nurses, care workers at child care and residential care facilities, as well as household and community service workers.

Based on CEPR’s analysis using the American Community Survey (2014 – 2018), over half of all essential workers in the industries examined are employed in care services. More than a third of these workers are over the age of 50; and before the pandemic, nearly a quarter were living in low-income households and about half lived with a child or a senior at home.

At the national level, women workers are overrepresented in frontline industries. About one-half of all workers are women, but nearly two-thirds (64.4 percent) of frontline workers are women. Women are particularly overrepresented in care-work related industries – Healthcare (76.8 percent of workers) and Child Care and Social Services (85.2 percent).

Black and Hispanic workers, as well as other people of color are also overrepresented in many frontline industries occupations. Black workers are most overrepresented in Child Care and Social Services (19.3 percent of workers). Hispanic workers are especially overrepresented in Building Cleaning Services (40.2 percent). Immigrants are also overrepresented in Building Cleaning Services and in many frontline occupations in other frontline industries.

The report calls on U.S. congress to include important protections for frontline workers in its response to COVID-19 – including comprehensive health-care insurance, paid sick and family leave, free child-care, student loan relief and other labor protections related to workers’ health, safety and immigration status.

About the report:

A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries. Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad. Center for Economic and Policy Research. April 2020.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19

Unpaid Work, Animated

About half of all the time devoted to work in the U.S. is devoted to unpaid work in the home. The Institute for New Economic Thinking has created an adorable animation of some comments I made in an interview with them on this topic a while back.

It’s quite a lot of fun, and basically accurate. Just don’t pay too much attention to the numbers they inserted into my discussion of two families, each with a market income of $50,000–the animation seems to imply that leisure should be assigned a monetary valuation–not something I advocate. Still, the main point comes through just fine: conventional measures provide a misleading picture of living standards.

The animation provides a great introduction to the topic for students, and you can find a more academic version of the basic argument in a short briefing paper I wrote for the Washington Center for Equitable Growth.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on June 11, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Expert Dialogues & Forums, Feminist Economics, Rethinking Macroeconomics

The Unpaid Care Work and the Labor Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys

How much time do people spend on doing paid and unpaid care work? How do women and men spend their time differently on unpaid care work? Are there any differences in time use among the regions? How do socioeconomic factors influence people’s choices to do paid and unpaid care work?

Jacques Charmes addresses these questions in recent ILO report by providing a comprehensive overview of the extent, characteristics and historical trends of unpaid care work. The report is based on the analysis of the most recent time-use surveys carried out at the national level across the world, revealing the differences in time spent on unpaid care work between women and men and among people with different socioeconomic characteristics, such as geographical location, age and income groups, education level, marital status and the presence and age of children in the household. An insightful discussion of the concepts and methodological approaches underlying the analysis of time-use data is also offered.

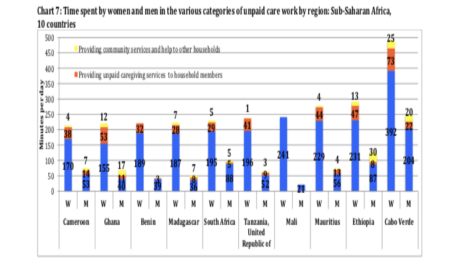

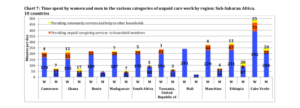

Chart 7 in the ILO Working Paper the Unpaid Care Work and the Labour Market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest World Compilation of Time-use Surveys illustrates the time spent by women and men in various categories of unpaid care work across Sub-Saharan African countries including Cameron, Ghana, Benin, Madagascar, South Africa, Tanzania, Mali, Mauritius, Ethiopia and Cabo Verde. As with the case around the world, women in Sub-Saharan African countries are providing significantly more unpaid care services in households and communities. Read the report to learn more about time-use analysis concepts and methodologies, gender variations in paid and unpaid work across the world and across various socio-economic levels:

International Labour Organization

Gender, Equality and Diversity & ILOAIDS Branch

This blog was authored by Shirin Arslan, Program Manager for the Care Work and the Economy Project

- Published in Child Care, elderly care, Policy Briefs & Reports

UN Women: COVID-19 and the Crisis of the Care Economy

In a recent UN Women blog post, Silke Staab explores ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic that has swept the globe is further compounding the risk and strain put upon women in the care economy – both paid and unpaid.

Women comprise 70% of health workers globally and even higher shares of care-related occupations such as nursing, midwifery and community health work, which all require close contact with patients. The risks these front-line workers take to save lives are compounded by poor working conditions, low pay and lack of voice in health systems where medical leadership is largely controlled by men.

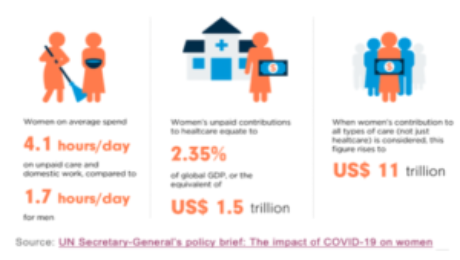

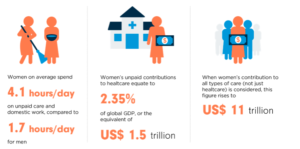

It is estimated that unpaid health care, in which the burden primarily fall onto women, is equivalent to a staggering $1.5 trillion globally. When factoring in all other types of care work, that figure climbs to $11 trillion. Furthermore, community health workers that receive no compensation, again mostly comprised of women, are vital to the health and wellbeing of communities all over the world. These care workers are in desperate need of proper equipment, training and financial support in the face of this current pandemic.

Source: UN Secretary-General’s policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on women

The increased burden of childcare due to school closures and social distancing is also bound to negatively affect the well-being of the women taking on these tasks. This is further exacerbated by the loss of assistance from elders in the family, who must keep themselves protected from COVID-19 due to being in a vulnerable category.

On the flip side of that is the reliance of elderly people on the informal care of their family members, but this reliance puts them at greater risk of being exposed. Providing these family care workers with the proper assistance and protective gear in order to continue their duties while minimizing the risk to their loved ones is an essential first step in facing this particular challenge.

Although this pandemic has caused an immense strain on the care economy, the situation has created an opportunity to reevaluate priorities and reassess the economic value of these essential services being provided through care work. A people-centered plan for economic recovery should take this into account and prioritize long-overdue investments in the care economy.

Silke Staab is a research specialist at UN Women.

This blog was originally posted on the UN Women website on April 22, 2020. Read this blog post here.

- Published in COVID 19, Gender Inequalities, UN Women

Responsibility Time

If there was ever a time we urgently needed to know more about time use, that time has come. The Covid-19 pandemic utterly changed daily rhythms for many sequestered households and the “opening up” process closed down some old routines.

I’ve done extensive work with time use data, have been in touch with several people/groups trying to measure the impact of the pandemic, and am trying to follow results being reported in other research.

My reactions are conditioned by long-standing concerns about survey methodology.

It is surprisingly hard to get an accurate picture of how people use time, because we all tend to do more than one thing at once. Also, doing is not the whole story—being present, available, on-call, and taking responsibility for others is typically far more time-consuming than specific acts of helping. This is especially true for the care of young children, people who are sick, frail, or suffering a disability.

Sheltering-in-place guidelines, combined with the social distancing, have probably had a much bigger impact on where people are, who they are with, and what they are responsible for—than on their activities.

Yet most surveys focus on activities alone, in several variations. They ask stylized questions about how much time people spent in various activities in a given time period, such as the previous day. Or, they persuade respondents to fill out a time diary in which they report what they did in specific intervals (such as every ten minutes) between waking up in the morning and going to sleep at night.

Note the prominence of the words “activities” and “doing” in both cases. Some surveys reach a bit further. The annual American Time Use Survey (ATUS), for instance, asks people if a child under the age of 13 was “in their care” while they engaged in activities. While the ATUS describes such care as a “secondary activity,” it is better interpreted as a responsibility that strongly influences the way that people organize their activities and plan their schedules.

Being on-call to provide care also creates vulnerability to brief but sometimes incessant interruptions whose impact is probably difficult to measure.

This is important because sheltering in place and sequestration almost certainly increased supervisory demands as much (if not more than) active care of young children. At the same time, social distancing guidelines limited peoples’ ability to provide any supervisory care or assistance to elderly or hospitalized family members.

Furthermore, these constraints are likely to be in place for some time—over the summer, children’s activities outside the home are likely to be restricted. Next fall, school schedules may be modified to reduce social density, by having some students come earlier or later in the day or spend some days at home learning on-line. Who will be on-call to supervise them?

From this perspective, consider some of the fascinating findings from on online survey of U.S. parents in mid-April reported in a recent briefing paper published by the Council on Contemporary Families (CCF). This survey was not based on a random sample (which would be hard to accomplish in a short time frame) and relied on stylized questions regarding time spent in specific activities.

The good news is that surveyed that mothers and fathers agree that fathers began doing more housework and childcare after the onset of the pandemic. This does not surprise me too much, since more men were at home, whether as a result of furlough, unemployment, or ability to telecommute. Like the authors of the paper, I’m hopeful that the experience of spending more time in proximity to kids will increase paternal engagement in the future.

The more striking finding, it seems to me, is that the pandemic did not increase time in domestic labor because some tasks like transporting children, attending children’s events, organizing children’s schedules/activities, and grocery shopping became less frequent.

This implies that time devoted to childcare activities declined even as on-call responsibilitiesincreased.

We need to know more about how parents experienced the intensification of such responsibilities. The CCF report is optimistic that the increased opportunities to perform paid work from home will promote a more egalitarian gender division of labor. I’m not so sure that paid work at home is viable for parents of young children without some delegation of supervisory responsibilities.

The CCF report devotes substantial attention to differences in mothers’ and fathers’ tallies of the way in which domestic responsibilities are allocated, an issue also highlighted by a recent surveys conducted by the New York Times and USA Today. These discrepancies highlight the greatest shortcoming of surveys based on stylized questions—women and men probably interpret questions differently, and reporting of relative participation (as in, who does more than whom) is particularly susceptible to social desirability bias.

Diary-based surveys—even if greatly abbreviated and simplified– would almost certainly yield more accurate results, especially if they included explicit attention to on-call responsibilities. Yet some additional stylized questions—especially about perceptions of supervisory constraints and the experience of doing paid work at home with young children present—would also be super helpful.

* I wish the ATUS also asked how much time sick or frail family members were “in your care” but it does not; nor is it clear how accurate responses to this question regarding children under the age of 13 are.

Original blog published on CARE TALK: FEMINIST AND POLITICAL ECONOMY on May 27th, 2020. See here for the original posting.

Reposted with permission from Dr. Nancy Folbre from University of Massachusetts Amherst and an expert researcher for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group.

- Published in Child Care, COVID 19, Policy Briefs & Reports, Time Use Survey