Current Situation of Care Work in South Korea: 2018 Family Survey

The Care Work and the Economy project’s 2018 fieldwork in South Korea helped us learn a great deal about how childcare and eldercare is provisioned, both in the paid and unpaid care sectors, in Korea.

The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys, including two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers and unpaid care providers. The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and recipients.

What We Learned about Family Caregiving in Korea

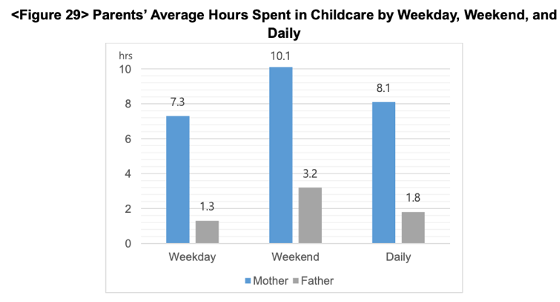

Although many families use at least one external care service to assist with childcare, 22% of respondents reported that their childcare was done only by family members (Kang et al.). Mothers spent six to seven hours more than fathers taking care of children on average.

(Kang et al.)

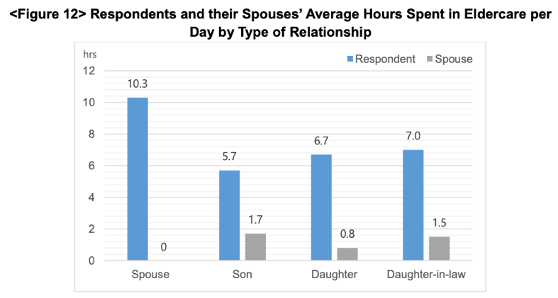

In contrast, 67% of respondents reported that their eldercare was done by family members; the rest reported using external care – usually the national LTC program. The primary caregivers were daughters-in-law (37% of the time), daughters (35%), spouses (15.6%), and sons (11%) (Kang et al.). Figure 12 shows how rather than the elder’s biological children, daughters-in-law provided the most care in terms of time, excepting the elder’s spouse.

(Kang et al.)

The cost of eldercare is shouldered solely by the primary caregiver in many cases (Kang et al., 2021)

Only 20% of family eldercare providers reported receiving regular financial support from other family members, less than 30% reported receiving help on an irregular basis, and only 8% of those over 65 years old were currently receiving LTC insurance program benefits.

Unpaid care provisioning impacts women’s employment.

The surveys showed that “families in which mothers were the sole caregiver for the child had the highest proportion of unemployed mothers, whereas families that received help with childcare from grandparents or paid care service had the highest proportion of employed mothers. With respect to both types of care arrangements, it was mostly daughters and daughters-in-law serving as primary caregiver, almost 70% of whom were unemployed.” (Kang et al.).

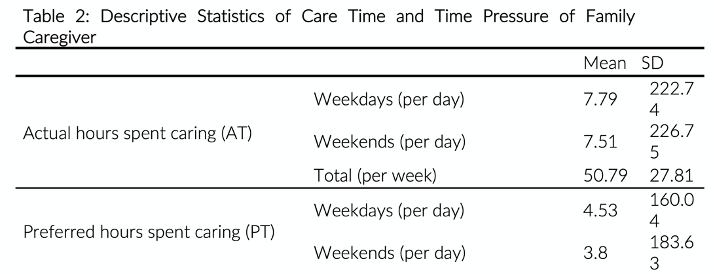

When asked about their preferred hours spent caring, eldercare workers reported a considerably lower number of hours on average than the actual hours they spent caring (see Table 2).

(Cha and Moon,2020)

Studies in the CWE-GAM Project stress concerns about the “quality of the caregiver’s life and the care they provide as well as the quality of life of the care recipient. Especially given that women are typically taking on the role of caregiver, this issue cannot be detached from concerns regarding women’s labor, women’s quality of life, and gender equality in Korea.”

Current Situation in Korea – Government Implications:

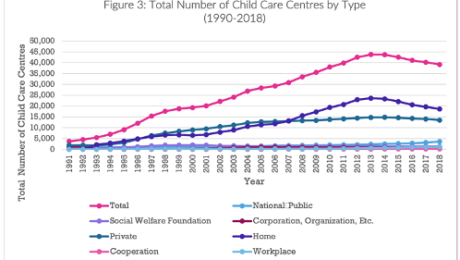

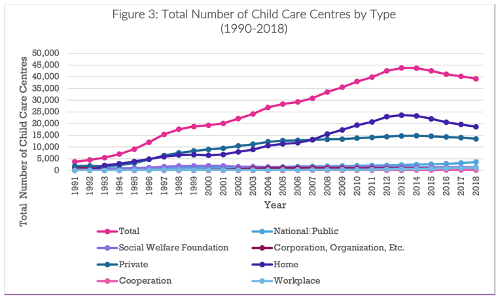

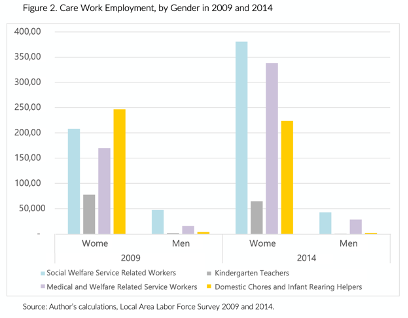

Korea currently “ranks amongst the top 10 OECD countries in terms of public investment in childcare and education” and implemented a mandatory universal LTCI program in 2008 (Peng et al 2021). Figure 2 and 3 show the evolution of child care and care work over time.

(Peng et al. 2021)

(Suh 2020)

Studies report that despite the social care expansion, “childcare and long-term care sectors are heavily dominated by women, and these care workers are largely poorly paid, over-worked, and precariously employed. Care work is also accorded low social and occupational status, and many care workers experience significant social and emotional stress” (Peng et al. 2021; Suh 2020).

Suh (2020) finds that “public investment in quality care services tends to improve the working conditions of care workers (thereby benefiting care recipients), and unregulated private provision tends to worsen them.”

This suggests that “the government and public sector should drive the effort to meet the multi-faceted challenges posed by the growing demand for care work” (Suh 2020).

“The Korean government […] continues to see care work as an extension of women’s unpaid care work and social care expenditure as something that need to be tightly controlled. A better understanding on the part of policymakers about the importance of care and the role of care work and the care economy in generating employment and positive economic growth and supporting a healthy productive economy is therefore necessary.” (Peng et al.)

This blog was contributed by Aina Krupinski Puig, Research Assistant for the Care Work and the Economy project.

References:

Cha, Seung-Eun, and Hyuna Moon. (2020). “A Glimpse of the Context of Family

Caregivers: Actual Time vs. Preferred Time for Elderly Care.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/dyfz-jp32.

Kang, Eunhye, Ki-Soo Eun, Jiweon Jun, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “Care

Arrangement and Activities in South Korea: An Analysis of the 2018 Care Work Family Survey on Childcare and Eldercare.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/8ZYD-AA52.

Peng, Ito, Seung-Eun Cha, and Hyuna Moon. (2021). “An Overview of Care Policies and the

Status of Care Workers in South Korea.” Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/EHN0-R646.

Suh, Joo Yeoun. (2020). “Estimating the Paid Care Sector in South Korea.” Care Work and the

Economy (CWE-GAM), Program on Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE), American University. https://doi.org/10.17606/bpdf-v686.

- Published in Child Care, Elder Care, Paid Care Services, Policy, South Korea, Unpaid Care Work

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part II

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” The discussion describes the interconnections between the crisis of care, the deepening ecological crisis and growth and accumulation processes.

There are many common threads with the climate and ecological crisis and the care crisis. Significantly, the idea that economic growth is overall beneficial. The type of economic growth generally pursued worldwide has not only increased stresses put upon the earth’s resource base but also on care labor capacity, which is similarly but wrongly perceived to be of infinite supply. Moreover, arguments that equate economic growth with overall improvement fail to recognize the distributional element of rising income inequality, which is far more nuanced. In fact, among countries that are higher income, gains from economic growth within those nations do not trickle down to everyone. When looking at care, the widening income equality gaps has shifted distribution of care givers across social classes and national boundaries. As a result, the quality and adequacy of care within a single nation can be very different, which exacerbates differences in social reproduction.

At the same time, income inequality has created a solution for the care needs of those that have the means to hire care for children and elderly, because care workers in those sectors are often paid low wages. But for the working poor, hiring care work help is inaccessible due to financial constraints, therefore they rely on their kinship networks to help provide this care. Furthermore, much of the care work burden still falls on women even as they enter to labor force. Economics and social policy in many parts of the world continue to neglect the heavy work burden put upon women and the necessity to balance household care activities and market work. What can also be observed is a global care supply chain, with the migration of women and girls to urban areas to provide care for wealthier families. Care itself is becoming one of the drivers of income inequality.

The economy is not all about material production; it is really about human vision and social provisions. However, an illusion has been created that unpaid care work is a natural resource that serves as an input for market production to promote GDP growth. However, this idea does not take into account that the wellbeing of people, especially the elderly, the sick and children should be an end in and of itself, to achieve sustainable growth. There is much work to be done to address these issues. To begin, economists must envision long term horizons that look forward to future generations while also taking into account the interdependence of life and moral responsibility. They must also integrate care and environmental consequences into our economic policy tools. Overall a new economic paradigm that includes green ecology and feminist economic concerns is needed.

Link to Part 1 of this blog here.

Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era: Part I

Faculti, an organization that presents digital media from leading experts and academics outlining their work, recently released a digital presentation by the Care Work and the Economy Principal Investigator Dr. Maria S. Floro entitled “Macroeconomic Policies, Care and Gender in the Post-COVID Era.” This discussion delves into the foundation of project itself, its context, the analytical tools utilized in the research, as well as the external factors that have served as the catalyst for the work being done.

The Care Work and the Economy Project was developed after a group of feminist economists observed that in the effort to reduce gender gaps in economic outcomes, as laid out within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, there were aspects of care work that needed to be addressed. The project includes 35 scholars from all around the world that are working to develop innovative analytical tools. The research has been applying and testing these tools in South Korea, a country that quickly industrialized in the 70s and 80s and therefore witnessed a very rapid demographic change in fertility and life expectancy.

The care economy, which is inclusive of caring for those that cannot care for themselves, underpins the production of all economies within society. This begins with the fact that if people stopped having children, which require care, then the economy would come to a halt due to lack of labor force. Generally, care work has a tendency to be undermined through a lack of gender awareness in macroeconomic modeling, which does not address care needs in any adequate manner. This aspect is also neglected within the policy making discourse, with the current economic paradigm failing to take into account the necessity for care work to achieve economic growth.

Economic models that display growth also fail to take into consideration social elements, making the assumptions that, for example, children will be cared for despite the lack of social investment into care. However, with care work there comes social, political and economic significance. The Care Work and the Economy project is working to demonstrate what a care focused macroeconomic model can reveal through the implementation of the analytic tools being developed and implemented through the research.

The absence of the care economy within macroeconomic models is in large part due to it being “invisible” since the work often unpaid. This has led to the neglect of care needs despite unpaid care work providing indispensable services in terms of economic activity and growth. The result is an emerging care crisis that has manifested itself in terms of uncared for elderly, sick and children. Furthermore, the crisis has provoked a form of silent protest against long unpaid work hours performed by women, leading to a decline in marriage and fertility rates. This in turn has resulted in a reproduction crisis.

The Care Work and the Economy project researchers are developing and using innovative analytical tools to bring care to the forefront, along with a deeper understanding of the nature of care work, while illustrating the intersectionality between care provisioning, economic growth and distribution. Although these analytical modeling tools are currently being applied in South Korea, the project believes they can be adopted and implemented into other countries as long as the provision of care is taken into context of those countries. The project research shows that governments have an important role and duty to invest in care provisions as well as comprehensive national care plans. One of the key findings is that it is important to take into account demographic change and climate change along with economic and structural changes taking place in policy making. This is a tall order but necessary to sustain economies and provide a future for next generation.

Link to Part 2 of this blog here.

This blog was authored by Jenn Brown, CWE-GAM Communications Assistant

A Narrative on Care

In 2018, the Care Work and the Economy (CWE-GAM) Project’s Understanding and Measuring Care (UMC) Working Group set out to gain a deeper understanding of the nature of care work and the well-being of caregivers in the context of South Korea. The group used a unique qualitative method combining in-depth interview and oral historical approach to investigate care as a continuously recurring activity throughout one’s life course and a necessary part of human existence. As part of the project’s qualitative field work and with the help of Gallup Korea, the UMC Working Group conducted 96 interviews between May – December 2018, bringing together 96 comprehensive narratives of care work in the South Korea context.

The CWE-GAM Project’s qualitative field work in South Korea conducted 96 in-depth interviews of paid and unpaid caregivers to provide useful care narratives based on the Korean context to inform macro-modelling. The qualitative research team interviewed 25 family caregivers of the elderly, 20 family caregivers of children, 20 paid care workers for elderly, and 31 paid care workers for children. The interviews of family caregivers focused on the decision-making process and evaluation of care arrangements for the elderly and children. In-depth interviews were combined with an oral historical approach to gain a deeper understanding of care work, emphasizing active listening to gain a more holistic understanding of the narrator’s life story on care. Interviewees were also asked about their experiences with caregiving. The interviews of paid caregivers focused on dual care burdens in terms of paid care work in addition to unpaid care work in the home. To learn more about the CWE-GAM Project’s qualitative field work in South Korea, read the Qualitative Methodology Report by the Care Work and the Economy UMC Working Group.

The following is one of the 96 stories. The respondent, Sung, lives with and cares for her mother, who was diagnosed with dementia about ten years ago.

*******************************

Date: May 29, 2018

Seocho-gu, Seoul

Interviewer: Hyuna Moon

Interviewee: Sung (pseudonym)

Sung, born in 1968, is 50 years old. She has a son and a daughter. They are both over 19 years old. One is attending college, and the other is studying for the college entrance exam. She is currently living with her children and her mother. As for siblings, she has one younger brother who is married. About ten years ago, Sung’s mother was diagnosed with dementia. Sung’s dad cared for her mom in the beginning, but her dad was also later diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Sung thus decided to move into her parents’ house to live together. It was by the time her first child entered middle school and her second child reached the upper grades in primary school. Her dad died four years ago, and she now looks after her mother. Her mother became a grade 3 beneficiary of the Long-Term Care Insurance (LTC) in her initial stage.

When Sung found out that her parents were ill, she didn’t think about passing the care duty to her brother. The siblings first considered making living arrangements so that each of them would live with one of their parents, for instance, Sung living with their dad and her brother living their mom, but their parents did not want this; they wanted to live together, not separately. Sung also felt that she ought to take care of her mother because of her ten years of experience living abroad, away from her parents. Sung has never thought that taking care of her frail parents is a son’s or a daughter-in-law’s duty. She didn’t think it was her brother’s duty to live with their parents and provide support. Nonetheless, her brother has taken up the role of financially supporting their parents. According to Sung, this was not negotiated but naturally happened. Sung and her brother also tried having their parents stay at her brother’s house during weekends, but it was always troublesome because he was not familiar with the situation, thus constantly calling up Sung for help. This weekday/weekend division of care duty did not work for them. Sung’s mother started going to the elderly daycare center from 2015 after her husband died. Her mother moved to a different center once because the center was located too far away from Sung’s place. Sung’s mother attended the first center for two years. When the center stopped running its shuttle bus to Sung’s house, Sung had to drive her mother to and from the center for a year. During that time, she had to hire a private caregiver who was responsible for driving Sung’s mother home in the evenings.

The hired caregiver also prepared meals and did some simple house chores for Sung. Sung paid her 1,000,000 KRW ($850 USD) every month, in addition to the monthly senior center fee of 300,000~400,000 KRW ( $250 – $335 USD). Other care-related expenses include Sung’s mother’s caregiver’s wage and other care services such as home-visit bathing service on weekends, food, medical bills and daily necessities such as diapers and etc., totaling about 2,000,000 KRW ($1,700 USD) per month. Sung’s brother helped to cover their mother’s care-related expenses, as Sung’s own income also had to cover her children’s education and living costs.

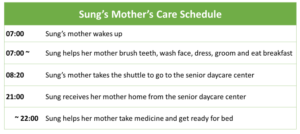

Description of Care Arrangement

Sung’s mother goes to the senior daycare center on weekdays and receives a home-visit bathing service every Saturday morning. The current elderly care center runs a shuttle that arrives at Sung’s house at 8:20 am to pick up her mother and to ride her back home at 9 pm. Sung’s mother is using the center service fully, spending the whole day at the center. Sung takes care of her mother after 9 pm until she goes to bed. When her mother comes back home, Sung helps her take medicine and changes her clothes and diapers. Her mother sleeps before 10 pm. Sung said her mother usually gets home tired after engaging in a variety of programs and activities offered all day long at the center.

Sung thinks her mother’s enrollment at the day care center is better than her staying at home and being bored. Sung said the most difficult part in caring for her mother happens at night, when her mother wakes up due to defecation. In such instances, Sung has to respond quickly to avoid what would otherwise become an even longer night, with her having to clean up the remains that will be all over the place. It got worse since last year and called for the most attention when caring for her mother. Nevertheless, Sung said her mother’s situation of dementia is not too bad, considering that some people with dementia can be very aggressive and easily agitated. Sung’s mother is relatively well-behaved, but she has this stubbornness which makes it difficult for Sung to help her get washed and change her underwear for she finds these to be a shame.

Sung said weekend care is tougher than weekday care because she needs to prepare food for every meal. The LTC-funded caregiver visits every Saturday to provide bath support, which is of great help, but Sung also needs to partake in the bathing assistance, requiring her presence.

The Cost of Caregiving

For Sung, it was an overload of work when she started supporting her parents by living together, while also having to care for her two adolescent children and working for her job at the same time. Sung said she had suffered from depression a few years ago due to the high stress of managing all her responsibilities. She had to seek psychiatric and medical treatments to overcome her depression.

Sung is considering sending her mother to the 24-hour nursing home as her health status is gradually deteriorating. She has applied for the institution for her mother’s stay, but she faces a long waiting list with more than 200 people. Sung said the reason for such a long waiting list is because this is a public nursing home, which is believed to provide better quality care and facilities.

Two years, she said, is what she thinks as the maximum number of years that she would be able to live with her mother if the current situation holds. But if it worsens, that is, if her mother’s dementia symptoms get worse, Sung will also consider sending her mother to some other facility with a shorter waiting list but also with lower quality of care.

She said that she would have to set a deadline to her caregiving for her own sake. She does not want to spend the rest of her 50s trapped with the care duty to her mother. Her children are now independent adults. Sung wants to start living her own life. She also feels she has done enough for her mother, her families and relatives all know it, and nobody will blame her for making this decision. Sung said because she is also a human, she needs to have her life and has the right to pursue it instead of sacrificing for her family.

****************************

See the surveys utilized for conducting this research below:

2018 South Korea Eldercare and Childcare Household Survey – Childcare

2018 South Korea Eldercare and Childcare Household Survey – Eldercare

Care Work and the Economy: Fieldwork in South Korea

The 2018 fieldwork for the CWE-GAM project aimed to understand and measure care work in the South Korean context in order to inform gender-aware care macroeconomic models. The fieldwork consisted of both quantitative and qualitative surveys. The quantitative surveys include two sets of questionnaires for paid care workers in eldercare and childcare (Paid Care Worker Survey) and two sets of questionnaires for the unpaid care providers in the households for eldercare and childcare (Care Work Family Survey). The qualitative component consists of two sets of in-depth interview questionnaires for care providers and care recipients.

PAID CARE WORK SURVEY

The Care Work and the Economy Paid Care Work Survey includes two sets of questionnaires for eldercare and childcare workers and a 24-hour time use diary. A purposive sampling method was used to sample 600 paid care workers, 300 eldercare workers and 300 childcare workers, because the exact size and distribution of paid care workers in Korea are unknown. Paid care workers are defined as those working in institutional settings, at the care recipients’ home, and informal workers working without formal contracts. The sample targeted those providing care of the elderly and children’s daily lives, excluding kindergarten teachers and health care workers at hospitals and medical eldercare facilities. The sample of paid care workers associated with institutions were allocated to reflect the national distributions of eldercare facilities and daycare centers, and the sample of informal care workers were equally allocated across regions.

The Paid Care Worker Survey collected detailed and comprehensive information on the care work provided by paid care workers. The stylized questions and time use diaries of paid care workers collect information on the type, intensity, duration, and evaluation of care work from the perspective of paid care providers. The survey aimed to investigate the characteristics and working conditions of paid care workers, including their background, condition of contract, working environment, task arrangement, and subjective evaluation of the working conditions, and their well-being. The 24-hour time use diaries were collected to provide insights on how the day of a care worker is constructed and how care work is associated with other domains of daily life and time use, which can be analyzed in tandem with the stylized questions on the well-being of care workers.

FAMILY CARE WORK SURVEY

The Care Work Family Survey also consists of two sets of questionnaires for main care providers in the household engaged in childcare and eldercare respectively. 1,000 cases of main care providers in the household were interviewed (500 cases for childcare, 500 cases for eldercare) using a stratified cluster sampling method. Because it is not possible to know the distribution of the population of people who provide unpaid care in a society, children aged below 10 and the elderly aged over 65 were treated as the target population from which to draw the sample. Based on the distribution of the 2018 National Resident Registration Data in Korea, we allocated the number of target households to each area, identified eligible households with elderly or children in need of care, and then selected eligible respondents within the selected households.

The Care Work Family Survey was developed to provide a detailed and comprehensive picture of the care arrangements in South Korea. The survey aimed to investigate how care provision is arranged for the children and the elderly and why it is arranged in such ways. Therefore, the survey collects information from the main care provider, not the care recipients themselves, as it is often the case that the main care provider is the one who knows most about the care arrangements.

After screening for eligibility, respondents were asked questions on their demographic characteristics and information on the respondent, care recipients and other household members. Respondents were asked about the specific activities involved with their care work including frequency, subjective intensity, preferences and willingness to engage in the activities. Information on care arrangements were collected as well including how the care work is shared within the household, whether there are any gaps of care provision, the history of caregivers, use of care services, and decision-making of using care services. Other information such as financial responsibility and burden, experience and evaluation of care work, dual care burdens and well-being of caregivers were collected.

IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

The purpose of the in-depth interviews of paid and unpaid caregivers was to provide useful care narratives based on the Korean context to inform macro-modelling. The qualitative research team intervened 25 family caregivers of the elderly, 20 family caregivers of children, 20 paid care workers for elderly, and 31 paid care workers for children. The interviews of family caregivers focused on the decision-making process and evaluation of care arrangements for the elderly and children. Interviewees were also asked about their experiences with caregiving. The interviews of paid caregivers focused on dual care burdens in terms of paid care work in addition to unpaid care work in the home.

SIGNIFICANCE AND LIMITATIONS

The fieldwork for paid and unpaid care work in Korea was designed and conducted to investigate the nature and context of care work in Korea. The Paid Care Worker Survey and Care Work Family Survey have distinct characteristics that contribute to enhancing our understanding about the experience of caregiving in Korea. First, the set of questions that have been developed can be commonly applied to caregivers regardless of the type of care work or the subject of care to enable comparative analysis on the experience of caregiving. Second, not only the caregiving situation, but also the broader aspect of the caregiver’s life including the preferences and attitudes of the caregiver have been studied. Third, the surveys collect detailed information on how care is arranged. Lastly, a caregiver focused 24-hour time use diary has been developed to understand which activities could be considered as care.

This fieldwork only included certain types of caregivers due to the limited budget, time, and scope of the fieldwork. For instance, the sample did not include caregivers for the disabled, caregivers who work at hospital settings, and migrant care workers, despite their importance. Also, as the family survey for childcare limited the respondents to ‘mothers’, and consequently fathers and grandparents were excluded. We hope that the future rounds of surveys can be extended to have a larger sample size and to include a broader range of caregivers. Questions explored in this fieldwork provide important information about the experience of caregiving in Korea, and we hope the fieldwork in Korea can inform fieldwork in other countries.

Learn more about care arrangements and activities in South Korea based on our analysis on the 2018 Care Work and Family Survey here.

This blog was authored by Bong (Regina) Sun Seo, contributing researcher for the Understanding and Measuring Care group

Reflections on The Effects of Public Social Infrastructure and Gender Equality on Output and Employment in South Korea

In terms of “Economic Participation and Opportunity” South Korea is one of the lowest-ranked countries in the world (124th out of 149 countries) as of 2018. Global Gender Gap Index also shows that South Korea ranks 88th in terms of female labour force participation and 121st in terms of gender wage equality for similar work. The average wages of women in South Korea are on average 36.7% lower than average male wages (as of 2012, Oyvat and Onaran, 2020). Hence, there is a significant economic gender gap in South Korea despite the fact that the country is now classified as a high-income economy. Moreover, the underdeveloped care infrastructure and reliance on unpaid care labour of women is posing serious demographic and social sustainability challenges in an aging society.

Our new research analyses the effects of public social expenditure in education, health and social care and closing gender pay gap on aggregate output and female and male employment (Oyvat and Onaran, 2020). We introduce a structuralist gendered model of the demand and supply sides of the economy with endogenous productivity, labour supply and wage bargaining. Empirically, we use a structural vector autoregression (SVAR) analysis to econometrically estimate the effects of an increase in social infrastructure spending, female and male wages, and closing the gender pay gap on aggregate output and employment of men and women in South Korea for the period of 1970-2012.

Public social expenditure, specifically education played an important role in the rise of South Korean economy. The social sector has not only been a sector that is crucial for economic growth in South Korea, but it has also been important for generating female employment and closing gender employment gaps. The share of women in employment in the social sector (education, healthcare and social care) has been greater than in the rest of the economy since the 1970s. The share of female employment in the social sector in South Korea increased from 47.4% during the period of 1988-1997 to 58.3% in 1998-2007 and to 63.2% in 2008-2012. In contrast, the share of female employment in the rest of the non-agricultural economy is only 27.7% in 1998-2007 and 28.4% in 2008-2012. The female employment share even in sectors which traditionally had a high female employment such as food, beverages, tobacco, textiles, leather, and footwear or electrical and optical equipment have been steadily declining and is lower than the female employment share in the social sector in the post-1998 period.

Our theoretical framework identifies the possible channels through which public social spending influences total output, male and female employment. In the short-run, the increase in public social spending has a positive effect on total output and female and male employment. While higher social public expenditure may increase public debt/GDP in the short-run, this negative effect is moderated as tax revenues also increase alongside aggregate income, which in turn offsets any potential crowding out effect on private investment. As the female employment share is significantly larger in the social sector than in the rest of the economy, higher public social expenditure is expected to reduce the gender employment gap.

In the medium-run, higher public social expenditure is expected to have not only a direct positive effect on labour productivity, but also an indirect positive effect through i) higher output and benefits of increasing returns to scale; ii) higher wages creating incentives for adopting labour-saving technologies; and iii) higher private expenditure in education, health and social care by the households as income, in particular female income increases. Due to these effects on productivity, we refer to public social expenditure as social infrastructure investment.

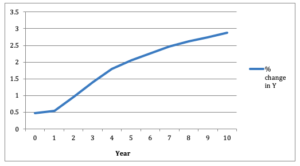

Figure 1: The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in social expenditure (YH) on aggregate non-agricultural output (Y)

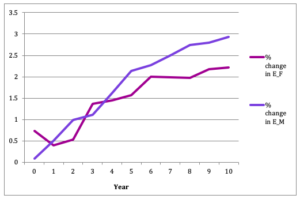

The estimation results show that a 1% increase in the public social expenditure in South Korea increases non-agricultural output by 0.5% contemporaneously, and by 2.3% in cumulative over six years and 2.9% over ten years (Figure 1). As a result female and male employment increase contemporaneously by 0.7% and 0.1% respectively (Figure 2). The short-run impact is larger for female employment as the share of women is significantly higher in the social sector compared to the rest of the non-agricultural sector. In ten years female and male employment increase by 2.2% and 2.9% respectively. Finally, labour productivity increases by 0.22% over four years.

Figure 2: The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in social expenditure (YH)on female (EF) and male employment (EM)

The results also show that an increase in female wage rate has a significant positive effect on output. A 1% increase in female wages leads to a cumulative increase in output by 0.2% in year 3 and by 0.3% over 10 years. This shows that the South Korean economy is female wage-led/gender equality-led in the medium-run; hence higher equality is conducive to growth and development. The cumulative impact of a 1% increase in the male wage rate on output is 0.2% over 10 years. It is also important to emphasize that higher male wages are not an impediment to growth in South Korea. The results also indicate the importance of improving gender equality as part of an equality-led development policy.

Our research shows that an equitable development path in which both average wages increase and gender gaps close via an upward convergence in the wages of men and women is possible in South Korea. However, the effects from wages are economically small in comparison to the strong effects of social spending. The results indicate that sustainable equitable development and a substantial increase in employment requires a mix of both labour market and fiscal policies.

This blog is authored by Cem Oyvat and Özlem Onaran are both expert researchers for the Care Work and the Economy Project within the Rethinking Macroeconomics working group. To learn more read the CWE-GAM working paper upon which this blog was based here.

- Published in Rethinking Macroeconomics, South Korea

“Being at Home” is Not Free – Making Informal Care Provision Visible and Providing Support During the Pandemic

The Japanese Government responded to the COVID 19 crisis by declaring a state of emergency and announcing an economic stimulus of 108 trillion yen, 6 trillion of which is allocated to households and small to midsized businesses. However, care work is not mentioned in this state of emergency. In the face of this pandemic, the government should be taking into account the increased burden of home care that is brought on in addition to the concerns regarding the collapse of medical care.

Although medical care is very important, home goes beyond medical care in terms of responsibilities. Take, for instance, an elderly person that has home aid providing essential forms of care – preparing meals, etc. These care workers are taking on huge risks and burdens, and the fact that neither policymakers nor the press are paying attention to this is problematic.

Additionally, as hospitals are overrun with the sickest patients, many those that have contracted COVID-19 are forced to stay home, leaving relatives, especially women, to care for them without the proper PPE or the vigorous sanitation needed. This will result in further spread of the virus, and each household will take on a similar pattern to what has been seen on cruise ships. Furthermore, in Japan, many people live in small homes, making it impossible to create “quarantined zones” within the home. There is also the consideration that many of those in isolation do not have a member of the household to do the shopping. Those individuals are left without access to basic provisions and this is especially the case amongst those that live alone.

Although Prime Minister Abe has thanked the medical staff and truck drivers, he has failed to mention the family care members and the important role they play, which might indicate that family care is seen as a mere obligation, as plentiful as water or air.

The government in South Korea has taken on a much different approach, taking note of these needs, it responded by providing provisions to those that are isolated at home and are unable to go shopping. These provisions show that publicly fulfilling care needs may help in preventing the spread of the disease.

Japan technically has similar measure in place under the Japanese Infectious Disease Control Law, which requires that the government must provide necessities in order to enable individuals to stay home to prevent the spread of infection. However, in actuality, this has not been the case. In Osaka, a modern welfare policy exists to provide coupons for residents for food delivery from local restaurants, helping both those in isolation and local small businesses. This is an example that could be replicated on a national scale with the cooperation of the government and private sector.

I created a survey with colleague Mr. Nanami Suziki to investigate the ease in which people can self-isolate. The survey was distributed through the internet in April 8th and as of April 12th , 330 responses were recorded. These results indicate that domestic work within the home is on the rise, with increasing burdens for those responsible for these tasks within the home. Furthermore, the increased domestic workload is putting strain on those who are remotely working from home.

Survey results show that although in many cases both men and women work remotely, women more often end up taking on all additional home responsibilities imposed by the pandemic, including homeschooling for the children.

As a result, many women are taking leave from their jobs, are working longer hours, and are becoming sleep deprived. Additionally, the increased family stress can lead to domestic violence. Policymakers and the press need to be more attentive to these increased burdens.

Steps can be taken to alleviate this situation, beginning with making care work visible and providing compensation. Further, ensuring employment and income those providing care for individuals in quarantine. This would follow the example set by South Korea in which those that cannot be paid to take leave can apply for living expenses to be supported through the government. As it stands now, Japanese relief policies fail to recognize the increased care burden being faced in the home, primarily by women.

Further, the government should respond by distributing lunch boxes to children that are not able to attend school due to closures, helping those children living in poor households that rely on school lunch. It is also important to support to the continuation of programs that are providing this sort of social care.

There have been some positive results from this situation, such as more family time and communication. Economy is only one aspect of life and moving forward, care work should be made visible in order to create a shift in society that mainstreams the value of “life” over “economy.”

* Thanks to Asahi Okamoto, Kaori Yamamoto, and Yoon Sodam.

This blog is authored by Emiko Ochiai who is a Professor of Sociology at Kyoto University.

Originally published in Japanese to the Women’s Action Network on Monday, April 13, 2020

- Published in COVID 19, Japan, Policy, South Korea

A Gendered Social Accounting Matrix for South Korea

A social accounting matrix (SAM) is an economy-wide consistent representation of the payments in an economy, linking production, primary factors, and institutions (the latter often split into households, government, and the rest of the world). In the words of Round (2003), “it is a comprehensive, flexible, and dis-aggregated framework which elaborates and articulates the generation of income by activities of production and the distribution and redistribution of income between social and institutional groups.” Most of the time, a SAM refers to the economy of a country for one year. It may be used to describe the structure of an economy and as a data input to economic models, most importantly CGE models. This paper documents a gendered Social Accounting Matrix (SAM) for South Korea for 2014: the steps followed in its construction, the data sources, and what the SAM says about the economic structure of this country (for brevity from now on referred to as Korea), including gender, time use, and the role of households in providing care and other services provided by households. The SAM that is presented is the key data input to a forthcoming analysis of gender and care in Korea’s economy based on GEM Care, a computable general equilibrium (CGE) model.

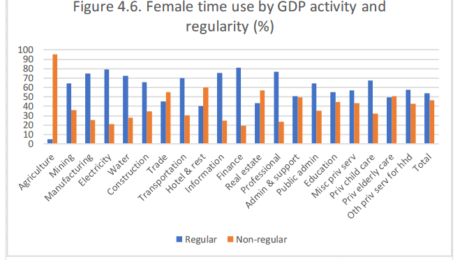

At an aggregate level, the value-added in the GDP economy is roughly 86 percent of the total (with agriculture, industry, services accounting for 2, 33, and 51 percent, respectively) and the non-GDP economy 14 percent. This information may be contrasted with aggregate time shares in terms of which, the non-GDP economy accounts for a much larger share, 40 percent. If leisure also were included, then it would on its own account for 50 percent of total time, 53 percent for men and 47 percent for women. The share of time allocated to household activities are drastically different for men and women, 15 and 57 percent, respectively. For women, non-care household services comprise the largest time using activity by a wide margin, followed by household childcare, trade services, and hotel and restaurant services. For men, manufacturing dominates, followed by trade services, household non-care services, and construction. For agriculture and industry, the lesser educated dominate all activities except electricity for both men and women. For services, the differences across sectors are drastic with some dominated by those with high education and others by those with low. These are few of the many descriptive findings from the gendered SAM developed by the authors.

This paper will be available December 2019.

This blog was authored by Binderiya Byambasuren, Kijong Kim & Hans Lofgren

Glimpse of Family Caregivers’ Context: Actual time vs. Desired time for Care

Attitudes towards family care are changing. Only 27% of Koreans surveyed in 2018 agreed that the family is responsible for elderly family member care. As for population aging, the middle age group of Korean society is becoming a true “Sandwiched Generation” (supporting both unmarried children and elderly parents) due to the longevity increase among elderly parents and postponement of marriage among the young generation. In addition, caring for grandchildren by the young elderly group is becoming more prevalent as the number of employed married women has increased in recent decades. To respond to this family burden, Long Term Care Insurance for the Elderly (LTCI) has been expanded since 2008. Statistics of the LTCI program show a stiff increase in care provision for supporting the daily lives of elderly who suffer from physical and mental ailments.

Cha & Moon (2019) investigate the nature of family care in the context of expanding public care provision. Using the 2018 Family Survey for Child and Elder Care, the authors assess the role of family care and how family members take part in the changing elderly care process. Family caregivers spend, on average, about 8 hours a day providing care to elderly family members on caring days, or about 50 hours a week. However, the average preferred number of hours for care is 24 hours per week, almost half of the actual care hours. Those who are classified as mildly or severely over-caring tend to live with their elderly family member, partly because the elder family member has a severe limitation in their Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and is unlikely to spend more than 3 hours per day alone.

On the other hand, care givers whose hours matched their desired hours are relatively young and the employment rate is higher than among other types. Compared to this matched case, over-caring is more common when attentiveness is required, when the caregiver perceives the necessity to take on greater responsibility for the elderly care recipient, and when time consuming care tasks are needed to care for the elderly family member. The authors speculate that the different types of care arrangements—under-caring, matched, and over-caring—appear to represent the sequential process of elderly care, from making regular care-visits to constantly ‘being there’ next to the recipient.

This paper will be available December 2019.

- 1

- 2